IPTI Xtracts- the Items Included in IPTI Xtracts Have Been Extracted from Published Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In New York State Politics Exposing the Influence of the Plaintiffs'

PO WER OF ATTORNEY 2015 Exposing the Influence of the Plaintiffs’ Bar in New York State Politics 19 Dove Street, Suite 201 Albany, NY 12210 518-512-5265 [email protected] www.lrany.org Power of Attorney: Exposing the Influence of the Plaintiffs’ Bar in New York State Politics, April 2015 Author/Lead Researcher: Scott Hobson Research Assistant: Katherine Hobday Cover image: Scott Hobson/Shutterstock Contents About the Lawsuit Reform Alliance of New York ............................................................. 3 Overview ............................................................................................................................ 3 Notes on Political Influence in New York ......................................................................... 4 Summary of Findings ........................................................................................................ 5 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 6 Findings ............................................................................................................................. 7 Lobbying ..................................................................................................................... 7 Lobbyists .................................................................................................................... 7 Campaign Contributions ............................................................................................ 8 Exploring the Influence -

Letter to Charles-Lavine.21.03.17

New York State Assembly KEVIN M. BYRNE KIERAN M. LALOR Assemblyman 94th District Assemblyman 105th District Westchester & Putnam Counties Dutchess County March 17, 2021 Honorable Charles D. Lavine Assemblymember & Chair of the Assembly Judiciary Committee Legislative Office Building 831 Albany, NY 12248 Chairman Charles Lavine: Throughout the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, our state has been tested in countless ways. Our work is not over, and the scandals coming from the Cuomo Administration have only added to the challenges we all face. The importance of the Judiciary Committee’s responsibility to investigate Governor Cuomo and the administration cannot be overstated. While it is important your committee is provided the time and resources it needs to conduct a thorough investigation, it is critical that there be no delays in your work. It would be wrong to afford Governor Cuomo and his administration the opportunity to further misuse his office by utilizing the budget process to impede or influence your investigation. In our state’s rich long history, only one Governor, William Sulzer, has ever been impeached. Like the Assembly Speaker did in 1913, Speaker Heastie has opted to begin the impeachment process with an investigative committee. The allegations against Governor Cuomo are far more serious and more numerous than those levied against Governor Sulzer, or more recently against Governor Elliot Spitzer. Many of these impeachable offenses were conducted in the middle of a pandemic when millions of New Yorkers were putting their faith in the Legislature and Governor Cuomo to be honest with them. The only thing that will restore the public’s trust in our state government is to provide New Yorkers the unvarnished truth in a timely manner. -

2019-2020 PAC Contributions

2019-2020 Election Cycle Contributions State Candidate or Committee Name Party -District Total Amount ALABAMA Sen. Candidate Thomas Tuberville R $5,000 Rep. Candidate Jerry Carl R-01 $2,500 Rep. Michael Rogers R-03 $1,500 Rep. Gary Palmer R-06 $1,500 Rep. Terri Sewell D-07 $10,000 ALASKA Sen. Dan Sullivan R $3,800 Rep. Donald Young R-At-Large $7,500 ARIZONA Sen. Martha McSally R $10,000 Rep. Andy Biggs R-05 $5,000 Rep. David Schweikert R-06 $6,500 ARKANSAS Sen. Thomas Cotton R $7,500 Rep. Rick Crawford R-01 $2,500 Rep. French Hill R-02 $9,000 Rep. Steve Womack R-03 $2,500 Rep. Bruce Westerman R-04 $7,500 St. Sen. Ben Hester R-01 $750 St. Sen. Jim Hendren R-02 $750 St. Sen. Lance Eads R-07 $750 St. Sen. Milton Hickey R-11 $1,500 St. Sen. Bruce Maloch D-12 $750 St. Sen. Alan Clark R-13 $750 St. Sen. Breanne Davis R-16 $500 St. Sen. John Cooper R-21 $750 St. Sen. David Wallace R-22 $500 St. Sen. Ronald Caldwell R-23 $750 St. Sen. Stephanie Flowers D-25 $750 St. Sen. Eddie Cheatham D-26 $750 St. Sen. Trent Garner R-27 $750 St. Sen. Ricky Hill R-29 $500 St. Sen. Jane English R-34 $1,500 St. Rep. Lane Jean R-02 $500 St. Rep. Danny Watson R-03 $500 St. Rep. DeAnn Vaught R-04 $500 St. Rep. David Fielding D-05 $500 St. Rep. Matthew Shepherd R-06 $1,000 St. -

A Look at the History of the Legislators of Color NEW YORK STATE BLACK, PUERTO RICAN, HISPANIC and ASIAN LEGISLATIVE CAUCUS

New York State Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus 1917-2014 A Look at the History of the Legislators of Color NEW YORK STATE BLACK, PUERTO RICAN, HISPANIC AND ASIAN LEGISLATIVE CAUCUS 1917-2014 A Look At The History of The Legislature 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The New York State Black, Puerto Rican, Hispanic and Asian Legislative Caucus would like to express a special appreciation to everyone who contributed time, materials and language to this journal. Without their assistance and commitment this would not have been possible. Nicole Jordan, Executive Director Raul Espinal, Legislative Coordinator Nicole Weir, Legislative Intern Adrienne L. Johnson, Office of Assemblywoman Annette Robinson New York Red Book The 1977 Black and Puerto Rican Caucus Journal New York State Library Schomburg Research Center for Black Culture New York State Assembly Editorial Services Amsterdam News 2 DEDICATION: Dear Friends, It is with honor that I present to you this up-to-date chronicle of men and women of color who have served in the New York State Legislature. This book reflects the challenges that resolute men and women of color have addressed and the progress that we have helped New Yorkers achieve over the decades. Since this book was first published in 1977, new legislators of color have arrived in the Senate and Assembly to continue to change the color and improve the function of New York State government. In its 48 years of existence, I am proud to note that the Caucus has grown not only in size but in its diversity. Originally a group that primarily represented the Black population of New York City, the Caucus is now composed of members from across the State representing an even more diverse people. -

IDEOLOGY and PARTISANSHIP in the 87Th (2021) REGULAR SESSION of the TEXAS LEGISLATURE

IDEOLOGY AND PARTISANSHIP IN THE 87th (2021) REGULAR SESSION OF THE TEXAS LEGISLATURE Mark P. Jones, Ph.D. Fellow in Political Science, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy July 2021 © 2021 Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and the Baker Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Baker Institute. Mark P. Jones, Ph.D. “Ideology and Partisanship in the 87th (2021) Regular Session of the Texas Legislature” https://doi.org/10.25613/HP57-BF70 Ideology and Partisanship in the 87th (2021) Regular Session of the Texas Legislature Executive Summary This report utilizes roll call vote data to improve our understanding of the ideological and partisan dynamics of the Texas Legislature’s 87th regular session. The first section examines the location of the members of the Texas Senate and of the Texas House on the liberal-conservative dimension along which legislative politics takes place in Austin. In both chambers, every Republican is more conservative than every Democrat and every Democrat is more liberal than every Republican. There does, however, exist substantial ideological diversity within the respective Democratic and Republican delegations in each chamber. The second section explores the extent to which each senator and each representative was on the winning side of the non-lopsided final passage votes (FPVs) on which they voted. -

Writing the State Budget: 87Th Legislature

March 8, 2021 No. 87-1 FOCUS on State Finance Initial budget development 1 Writing the state budget Writing and passing a biennial budget 2 Writing a budget is one of the Texas Legislature’s main tasks. The state’s budget is written General appropriations and implemented in a two-year cycle that includes development of the budget, passage of the bill 4 general appropriations act, actions by the comptroller and governor, and interim monitoring. During the 2021 regular session, the 87th Legislature will consider a budget for fiscal 2022- Legislative action 5 23, the two-year period from September 1, 2021, through August 31, 2023. Action after final passage 7 Initial budget development Interim budget action 7 Developing the budget begins with state agencies receiving instructions for submitting budget requests. Agencies then submit their budget proposals, and hearings are held on Restrictions on spending 8 their requests. Next, the Legislative Budget Board (LBB) adopts a growth rate that limits appropriations, the comptroller issues an estimate of available revenue, and preliminary budgets are drafted. Pre-session budget instructions and hearings. State agencies are required in even- numbered years to develop five-year strategic plans (Government Code sec. 2056.002) that include agency goals, strategies for accomplishing those goals, and performance measures. Before a regular legislative session begins, agencies submit funding requests to the governor’s budget office and the LBB. These requests are called Legislative Appropriations Requests, or LARs. The LARs have two parts: the base-level request and requests for exceptional items beyond the baseline. In August 2020, state agencies were instructed to submit spending requests with base funding equal to their adjusted fiscal 2020-21 base. -

The Geography—And New Politics—Of Housing in New York City Public Housing

The Geography—and New Politics—of Housing in New York City Public Housing Tom Waters, Community Service Society of New York, November 2018 The 178,000 public housing apartments owned and operated by the New York City Housing Authority are often de- scribed as “a city within a city.” The Community Service Society has estimated the numbers of public housing apartments for the New York City portion of each legislative district in the city. These estimates were made by assigning buildings within public housing developments to legislative districts based on their addresses. United States Congress District U.S. Representative Public Housing 13 Adriano Espaillat 34,180 8 Hakeem Jeffries 33,280 15 José Serrano 32,210 7 Nydia Velazquez 26,340 12 Carolyn Maloney 10,290 9 Yvette Clarke 9,740 11 Max Rose 6,130 5 Gregory Meeks 5,980 10 Jerrold Nadler 5,530 14 Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez 5,500 16 Eliot Engel 4,630 6 Grace Meng 3,410 3 Tom Suozzi 0 New York State Senate District Senator Public Housing 30 Brian Benjamin 28,330 25 Velmanette Montgomery 16,690 32 Luis Sepúlveda 16,590 19 Roxanne J. Persaud 14,570 29 José M. Serrano 13,920 Learn more at www.cssny.org/housinggeography Community Service Society New York State Senate (cont.) District Senator Public Housing 18 Julia Salazar 13,650 26 Brian Kavanagh 12,020 23 Diane J. Savino 9,220 20 Zellnor Myrie 7,100 12 Michael Gianaris 6,420 33 Gustavo Rivera 5,930 36 Jamaal Bailey 5,510 31 Robert Jackson 5,090 10 James Sanders Jr. -

Peoples-Stokes

Assemblywoman Summer 2018 Crystal D. Peoples-Stokes Community News Assemblywoman Peoples-Stokes just concluded a very successful legislative session in Albany and is eager to continue her work back home in the district. Dear Friends and Neighbors: Summer is in full swing, I hope everyone is staying safe, having fun and enjoying this fantastic weather. It’s also time for my post session report to you on the progress I’ve been making as your State representative in the Assembly. I’m proud to say that the state budget included much-needed resources for Buffalo. Specifically, it included increases for healthcare, education, economic and workforce development funding. This letter details some of those increases as well as the bills I was the prime sponsor of that passed the Assembly and are awaiting the Governor’s signature. I look forward to continuing to engage my constituents and community stakeholders to increase the quality of life for all of our residents. Sincerely, Crystal D. Peoples-Stokes Legislative Lane Bills That Passed Both Houses, Now Awaiting Governor’s Signature A1789 - Directs the director of the division of minority and women’s business development Bills that have been Chaptered (Signed into Law) to provide for the minority and women-owned business certification of business entities owned Chapter 47: A2131 - Provides that each state agency that maintains by Indian nations or tribes a website shall ensure its website provides for online submission of requests for records subject to FOIL A2279A - Authorizes cities having a -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT New York State Assembly Carl E. Heastie Speaker Committee on Codes Joseph R. Lentol Chair THE ASSEMBLY CHAIR Committee on Codes STATE OF NEW YORK COMMITTEES ALBANY Rules Ways & Means Election Law JOSEPH R. LENTOL th Assemblyman 50 District Kings County [email protected] December 15, 2017 Honorable Carl Heastie Speaker of the Assembly 932 Legislative Office Building Albany, New York 12248 Re: Annual Report of the Standing Committee on Codes – 2017 Dear Speaker Heastie: It is with great pleasure that on behalf of the Standing Committee on Codes, I submit to you the committee’s 2017 Annual Report highlighting its activities during the first half of the 2017- 2018 Legislative Session. Among the committee’s many accomplishments was the enactment of several bills related to the reform of our state’s criminal justice system– most notably legislation to increase the age of criminal responsibility and to improve the quality of the public defense system. The Assembly also approved a series of bills to provide further protections to victims of domestic violence, sex crimes, and human trafficking. Further, the committee worked with other standing committees to enact legislation to protect children and other vulnerable populations. The Assembly can be justly proud of our legislative accomplishments which are set forth in this report. The committee extends its appreciation to you for your support. In addition, I would like to thank the committee members and staff for their hard work during the 2017 Legislative Session. Sincerely, Joseph R. Lentol, Chair Standing Committee on Codes 2017 ANNUAL REPORT NEW YORK STATE ASSEMBLY STANDING COMMITTEE ON CODES Joseph R. -

Legislative Staff: 87Th Legislature

HRO HOUSE RESEARCH ORGANIZATION Texas House of Representatives Legislative Staff 87th Legislature 2021 Focus Report No. 87-2 House Research Organization Page 2 Table of Contents House of Representatives ....................................3 House Committees ..............................................15 Senate ...................................................................18 Senate Committees .............................................22 Other State Numbers...........................................24 Cover design by Robert Inks House Research Organization Page 3 House of Representatives ALLEN, Alma A. GW.5 BELL, Cecil Jr. E2.708 Phone: (512) 463-0744 Phone: (512) 463-0650 Fax: (512) 463-0761 Fax: (512) 463-0575 Chief of staff ...........................................Anneliese Vogel Chief of staff .............................................. Ariane Marion Legislative director ................................. Adoneca Fortier Legislative aide......................................Joshua Chandler Legislative aide.................................... Sarah Hutchinson BELL, Keith E2.414 ALLISON, Steve E1.512 Phone: (512) 463-0458 Phone: (512) 463-0686 Fax: (512) 463-2040 Chief of staff .................................................Rocky Gage Chief of staff .................................... Georgeanne Palmer Legislative director/scheduler ...................German Lopez Legislative director ....................................Reed Johnson Legislative aide........................................ Rebecca Brady ANCHÍA, Rafael 1N.5 -

Texas House of Representatives Contact Information - 2017 Representative District Email Address (512) Phone Alma A

Texas House of Representatives Contact Information - 2017 Representative District Email Address (512) Phone Alma A. Allen (D) 131 [email protected] (512) 463-0744 Roberto R. Alonzo (D) 104 [email protected] (512) 463-0408 Carol Alvarado (D) 145 [email protected] (512) 463-0732 Rafael Anchia (D) 103 [email protected] (512) 463-0746 Charles "Doc" Anderson (R) 56 [email protected] (512) 463-0135 Rodney Anderson (R) 105 [email protected] (512) 463-0641 Diana Arévalo (D) 116 [email protected] (512) 463-0616 Trent Ashby (R) 57 [email protected] (512) 463-0508 Ernest Bailes (R) 18 [email protected] (512) 463-0570 Cecil Bell (R) 3 [email protected] (512) 463-0650 Diego Bernal (D) 123 [email protected] (512) 463-0532 Kyle Biedermann (R) 73 [email protected] (512) 463-0325 César Blanco (D) 76 [email protected] (512) 463-0622 Dwayne Bohac (R) 138 [email protected] (512) 463-0727 Dennis H. Bonnen (R) 25 [email protected] (512) 463-0564 Greg Bonnen (R) 24 [email protected] (512) 463-0729 Cindy Burkett (R) 113 [email protected] (512) 463-0464 DeWayne Burns (R) 58 [email protected] (512) 463-0538 Dustin Burrows (R) 83 [email protected] (512) 463-0542 Angie Chen Button (R) 112 [email protected] (512) 463-0486 Briscoe Cain (R) 128 [email protected] (512) 463-0733 Terry Canales (D) 40 [email protected] (512) 463-0426 Giovanni Capriglione (R) 98 [email protected] (512) 463-0690 Travis Clardy (R) 11 [email protected] (512) 463-0592 Garnet Coleman (D) 147 [email protected] (512) 463-0524 Nicole Collier (D) 95 [email protected] (512) 463-0716 Byron C. -

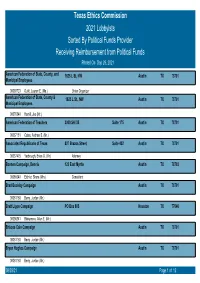

Texas Ethics Commission 2021 Lobbyists Receiving

Texas Ethics Commission 2021 Lobbyists Sorted By Political Funds Provider Receiving Reimbursement from Political Funds Printed On Sep 29, 2021 American Federation of State, County, and 1625 L St, NW Austin TX 78701 Municipal Employees 00085723 Guild, Lauren E. (Ms.) Union Organizer American Federation of State, County & 1625 L St., NW Austin TX 78701 Municipal Employees 00070846 Hamill, Joe (Mr.) American Federation of Teachers 3000 SH I35 Suite 175 Austin TX 78701 00067181 Cates, Andrew S. (Mr.) Associated Republicans of Texas 807 Brazos Street Suite 402 Austin TX 78701 00037475 Yarbrough, Brian G. (Mr.) Attorney Bonnen Campaign, Dennis 122 East Myrtle Austin TX 78703 00085040 Eichler, Shera (Mrs.) Consultant Brad Buckley Campaign Austin TX 78701 00061160 Berry, Jordan (Mr.) Brett Ligon Campaign PO Box 805 Houston TX 77046 00056241 Blakemore, Allen E. (Mr.) Briscoe Cain Campaign Austin TX 78701 00061160 Berry, Jordan (Mr.) Bryan Hughes Campaign Austin TX 78701 00061160 Berry, Jordan (Mr.) 09/29/21 Page 1 of 12 Buckingham Campaign, Dawn P.O. Box 342524 Austin TX 78701 00055627 Blocker, Trey J. (Mr.) Attorney Burrows Campaign, Dustin P.O. Box 2569 Austin TX 78703 00085040 Eichler, Shera (Mrs.) Consultant Capriglione, Giovanni (Rep.) 1352 Ten Bar Trail AUSTIN TX 78767 00068846 Lawson, Drew (Mr.) Lobby Charles "Doc" Anderson Campaign P.O. Box 7752 Austin TX 78747 00053964 Smith, Todd M. (Mr.) Impact Texas Communicaions, LLP Charles Perry Campaign Austin TX 78701 00061160 Berry, Jordan (Mr.) Claudia Ordaz Perez for Texas PO Box 71738 El Paso TX 79943 00053635 Smith, Mark A. (Mr.) Lobbyist Cody Vasut Campaign Austin TX 78701 00061160 Berry, Jordan (Mr.) Cole Hefner Campaign Austin TX 78701 00061160 Berry, Jordan (Mr.) Contaldi, Mario (Dr.) 7728 Mid Cities Blvd Austin TX 78705 00012897 Avery, Bj (Ms.) Texas Optometric Asso.