Leonard Cohen Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hallelujah Leonard Cohen

Hallelujah Leonard Cohen I've heard that there’s a secret chord That David played, and it pleased the Lord But you don't really care for music, do you? It goes like this The fourth, the fifth The minor fall, the major lift The baffled king composing Hallelujah Hallelujah x 4 You say I took the name in vain But I don't even know the name And if I did, well really, what's it to you? There's a blaze of light In every word It doesn't matter what you’ve heard The holy or the broken Hallelujah Hallelujah x 4 I did my best, it wasn't much I couldn't feel, so I tried to touch I've told the truth, I didn't come to fool you And even though it all went wrong I stand before the Lord of Song With nothing on my tongue but Hallelujah Hallelujah x 4 "Hallelujah" is a song written by Canadian singer Leonard Cohen, originally released on his album Various Positions (1984). Achieving little initial success, the song found greater popular acclaim through a recording by John Cale, which inspired a recording by Jeff Buckley. It has been viewed as a "baseline" for secular hymns. Following its increased popularity after being featured in the film Shrek (2001), many other arrangements have been performed in recordings and in concert, with over 300 versions known. The song has been used in film and television soundtracks and televised talent contests. "Hallelujah" experienced renewed interest following Cohen's death in November 2016 and appeared on many international singles charts, including entering the American Billboard Hot 100 for the first time. -

Jazz and the Cultural Transformation of America in the 1920S

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s Courtney Patterson Carney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Carney, Courtney Patterson, "Jazz and the cultural transformation of America in the 1920s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 176. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/176 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. JAZZ AND THE CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION OF AMERICA IN THE 1920S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Courtney Patterson Carney B.A., Baylor University, 1996 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2003 For Big ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The real truth about it is no one gets it right The real truth about it is we’re all supposed to try1 Over the course of the last few years I have been in contact with a long list of people, many of whom have had some impact on this dissertation. At the University of Chicago, Deborah Gillaspie and Ray Gadke helped immensely by guiding me through the Chicago Jazz Archive. -

Full Results of Survey of Songs

Existential Songs Full results Supplementary material for Mick Cooper’s Existential psychotherapy and counselling: Contributions to a pluralistic practice (Sage, 2015), Appendix. One of the great strengths of existential philosophy is that it stretches far beyond psychotherapy and counselling; into art, literature and many other forms of popular culture. This means that there are many – including films, novels and songs that convey the key messages of existentialism. These may be useful for trainees of existential therapy, and also as recommendations for clients to deepen an understanding of this way of seeing the world. In order to identify the most helpful resources, an online survey was conducted in the summer of 2014 to identify the key existential films, books and novels. Invites were sent out via email to existential training institutes and societies, and through social media. Participants were invited to nominate up to three of each art media that ‘most strongly communicate the core messages of existentialism’. In total, 119 people took part in the survey (i.e., gave one or more response). Approximately half were female (n = 57) and half were male (n = 56), with one of other gender. The average age was 47 years old (range 26–89). The participants were primarily distributed across the UK (n = 37), continental Europe (n = 34), North America (n = 24), Australia (n = 15) and Asia (n = 6). Around 90% of the respondents were either qualified therapists (n = 78) or in training (n = 26). Of these, around two-thirds (n = 69) considered themselves existential therapists, and one third (n = 32) did not. There were 235 nominations for the key existential song, with enormous variation across the different respondents. -

Preliminary Syllabus MUS 20: the Poetry and Songs of Leonard Cohen Instructor, T

Preliminary Syllabus MUS 20: The Poetry and Songs of Leonard Cohen Instructor, T. Hampton Recommended book: Cohen, Stranger Music. First Meeting, Oct 11: “Remember me, I used to live for music.” The poet as songwriter. Montréal. The Canadian Scene. Irving Layton. Cohen in Greece: Let Us Compare Mythologies, Songs of Leonard Cohen, Songs from a Room. Key Songs: “Suzanne,” “Sisters of Mercy,” “Stranger Song,” “Bird on the Wire,” “Story of Isaac,” “Seems So Long Ago, Nancy,” “So Long, Marianne.” Themes: flesh and spirit, the identity of the singing voice, abjection and humiliation. Second Meeting, Oct 18: “It’s four in the morning, the end of December.” Cohen in the spotlight. The Chelsea Hotel. Isle of Wight. Cohen on the move. Songs of Love and Hate, New Skin for the Old Ceremony. Key Songs: “Famous Blue Raincoat,” “Joan of Arc,” “Who by Fire,” “A Singer Must Die,” “Take This Longing,” “Dress Rehearsal Rag.” Themes: limits of power, self-doubt, drugs, self-purification, betrayal. Third Meeting, Oct 25: “I will speak no more, till I am spoken for.” Cohen as “The Prince of Bummers.” Death of a Lady’s Man. Death of a Ladies Man. Recent Songs. Various Positions. Key Songs: “If It Be Your Will,” “Hallelujah,” “Coming Back to You.” “The Guests.” “The Smoky Life,” “Dance Me to the End of Love.” Jennifer Warnes, Famous Blue Raincoat. Themes: Humility, divinity, Impotence. Fourth Meeting, Nov. 1: “I was born like this, I had no choice.” Cohen Returns. The importance of the keyboard. New production values. Book of Mercy. Book of Longing. I’m Your Man. -

Cohen's Age of Reason

COVER June 2006 COHEN'S AGE OF REASON At 71, this revered Canadian artist is back in the spotlight with a new book of poetry, a CD and concert tour – and a new appreciation for the gift of growing older | by Christine Langlois hen I mention that I will be in- Senior statesman of song is just the latest of many in- terviewing Leonard Cohen at his home in Montreal, female carnations for Cohen, who brought out his first book of po- friends – even a few younger than 50 – gasp. Some offer to etry while still a student at McGill University and, in the Wcome along to carry my nonexistent briefcase. My 23- heady burst of Canada Council-fuelled culture of the early year-old son, on the other hand, teases me by growling out ’60s, became an acclaimed poet and novelist before turning “Closing Time” around the house for days. But he’s inter- to songwriting. Published in 1963, his first novel, The ested enough in Cohen’s songs to advise me on which ones Favourite Game, is a semi-autobiographical tale of a young have been covered recently. Jewish poet coming of age in 1950s Montreal. His second, The interest is somewhat astonishing given that Leonard the sexually graphic Beautiful Losers, published in 1966, has Cohen is now 71. He was born a year before Elvis and in- been called the country’s first post-modern novel (and, at troduced us to “Suzanne” and her perfect body back in 1968. the time, by Toronto critic Robert Fulford, “the most re- For 40 years, he has provided a melancholy – and often mor- volting novel ever published in Canada”). -

The End of the World and Other Times in the Future

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Philosophy Faculty Publications Philosophy 2014 The ndE of the World and Other Times in The Future Gary Shapiro University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/philosophy-faculty- publications Part of the Composition Commons, and the Philosophy of Language Commons Recommended Citation Shapiro, Gary. "The ndE of the World and Other Times in The Future." In Leonard Cohen and Philosophy: Various Positions, edited by Jason Holt, 39-51. Vol. 84. Popular Culture and Philosophy. Chicago: Open Court, 2014. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4 The End of the World and Other Times in The Future GARY SHAPIRO In an interview with his biographer Sylvie Simmons, Leonard Cohen identifies the main interests in his work as "women, song, religion" (p. 280). These are not merely per sonal concerns for Cohen, they are dimensions of the world that he tries to understand as a poet, singer, and thinker. Now it's something of a cliche to see the modern romantic or post-romantic singer or poet in terms of personal strug gles, failures, triumphs, and reversals. Poets sometimes re spond by adopting elusive, ironic, enigmatic, or parodic voices: think, in their different ways, of Bob Dylan and Anne Carson. Yet Cohen has always worn his heart on his sleeve or some less clothed part of his body: he let us know, for ex ample, that Janis Joplin gave him head in the Chelsea hotel while their celebrity limos were waiting outside. -

The Compositional Style of Jazz Guitarist Nathen Page

University of North Florida UNF Digital Commons All Volumes (2001-2008) The sprO ey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry 2004 Artist Study: The ompC ositional Style of Jazz Guitarist Nathen Page Stephen Lesche University of North Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ojii_volumes Part of the Composition Commons Suggested Citation Lesche, Stephen, "Artist Study: The ompositC ional Style of Jazz Guitarist Nathen Page" (2004). All Volumes (2001-2008). 89. http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ojii_volumes/89 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The sprO ey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Volumes (2001-2008) by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2004 All Rights Reserved Artist Study: The Compositional his mastery because he does not compare Style of Jazz Guitarist Nathen to other guitarists that they have listened Page to. In spite of this, this is exactly why he is so great: he plays like himself. His tone is all his own and I have grown to Stephen Lesche enjoy it. His approach to technique is also very personalized. While he may Faculty Sponsor: Kevin Bales, not be able to produce rapid flurries of Assistant Professor of Music sixteenth notes like some of his contemporaries can, this has never Nathen Page is one of the hindered him in expressing himself and masters of modern jazz guitar. producing music of the highest caliber. Unfortunately, he is also one of the least In developing as an artist, there known and recognized of the masters. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. JON HENDRICKS NEA Jazz Master (1993) Interviewee: Jon Hendricks (September 16, 1921 - ) and, on August 18, his wife Judith Interviewer: James Zimmerman with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: August 17-18, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 95 pp. Zimmerman: Today is August 17th. We’re in Washington, D.C., at the National Portrait Galley. Today we’re interviewing Mr. Jon Hendricks, composer, lyricist, playwright, singer: the poet laureate of jazz. Jon. Hendricks: Yes. Zimmerman: Would you give us your full name, the birth place, and share with us your familial history. Hendricks: My name is John – J-o-h-n – Carl Hendricks. I was born September 16th, 1921, in Newark, Ohio, the ninth child and the seventh son of Reverend and Mrs. Willie Hendricks. My father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the AME Church. Zimmerman: Who were your brothers and sisters? Hendricks: My brothers and sisters chronologically: Norman Stanley was the oldest. We call him Stanley. William Brooks, WB, was next. My sister, the oldest girl, Florence Hendricks – Florence Missouri Hendricks – whom we called Zuttie, for reasons I never For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 really found out – was next. Then Charles Lancel Hendricks, who is surviving, came next. Stuart Devon Hendricks was next. Then my second sister, Vivian Christina Hendricks, was next. Then Edward Alan Hendricks came next. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

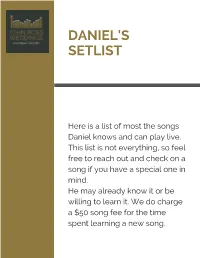

Daniel Setlist

DANIEL'S SETLIST Here is a list of most the songs Daniel knows and can play live. This list is not everything, so feel free to reach out and check on a song if you have a special one in mind. He may already know it or be willing to learn it. We do charge a $50 song fee for the time spent learning a new song. Pop/Rock/Folk/Jazz/Country: A Thousand Years - Christina Perry Ain’t No Sunshine - Bill Withers Barton Hollow - The Civil Wars Best Things in Life - Brandon Reed Better Than I Used to Be - Mat Kearney Billie Jean - Michael Jackson Can't help falling in love - Elvis Presley Charlie Brown - Coldplay Clocks - Coldplay Diamonds - Johnnyswim Drink You Away - Justin Timberlake Fix You - Coldplay Free Fallin - Tom Petty / John Mayer version From This Valley - The Civil Wars Galway Girl - Ed Sheeran God Bless the Broken Road - Rascal Flatts Gravity - John Mayer Hallelujah - Leonard Cohen Happier - Ed Sheeran Ho Hey - The Lumineers How long will I love you - Ellie Goulding I Got A Woman - Ray Charles I Just Called To Say I Love You - Stevie Wonder Isn’t She Lovely - Stevie Wonder Just The Way You Look Tonight - Frank Sinatra L O V E - Nat King Cole Love me like you do - Ellie Goulding Love Yourself - Justin Bieber Paradise - Coldplay Perfect - Ed Sheeran Portland, Maine - Tim McGraw Rude - Magic Senorita - Justin Timberlake She Will Be Loved - Maroon 5 Stand By Me - Ben E. King Sugar - Maroon 5 Suit and Tie - Justin Timberlake Sunday Morning - Maroon 5 Superstition - Stevie Wonder Take the World - Johnnyswim Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton The A Team - Ed Sheehan The Bed I Made - Allen Stone The scientist - Coldplay Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheehan Till I Found You - Phil Wickham Touching Heaven - Johnnyswim Viva La Vida - Coldplay Waiting On The World to Change - John Mayer Wildfire - John Mayer Religious: Over 100 worship songs from artists such as: Phil Wickham, Elevation, Hillsong, Jesus Culture, Bryan and Katie Torwalt, Corey Asbury, Michael W Smith, Bethel Music, etc. -

Leonard Cohen in French Culture: a Song of Love and Hate

The Journal of Specialised Translation Issue 29 – January 2018 Leonard Cohen in French culture: A song of love and hate. A comparison between musical and literary translation Francis Mus, University of Liège and University of Leuven ABSTRACT Since his comeback on stage in 2008, Leonard Cohen (1934-2016) has been portrayed in the surprisingly monolithic image of a singer-songwriter who broke through in the ‘60s and whose works have been increasingly categorised as ‘classics’. In this article, I will examine his trajectory through several cultural systems, i.e. his entrance into both the French literary and musical systems in the late ‘60s and early ’70s. This is an example of mediation brought about by both individual people and institutions in both the source and target cultures. Cohen’s texts do not only migrate between geo-politically defined source and target cultures (Canada and France), but also between institutionally defined musical and literary systems within one single geo-political context (France). All his musical albums were reviewed and distributed there soon after their release and almost his entire body of literary works (novels and poetry collections) has been translated into French. Nevertheless, Cohen’s reception has never been univocal, either in terms of the representation of the artist or in terms of the evaluation of his works, as this article concludes. KEYWORDS Leonard Cohen, cultural transfer, musical translation, retranslation, ambivalence. I don’t speak French that well. I can get by, but it’s not a tongue I could ever move around in in a way that would satisfy the appetites of the mind or the heart. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan.