Kickstarting Growth in Bus Patronage: Targeting Support at the Margins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where to Catch Your Bus in Colchester Town Centre

Where to catch your bus in Colchester Town Centre W E S E WIL LIA M ’S WA T LK A MA Colchester Town Centre G Colchester S S E T T O I Castle D O S R Bus Stops S C T E T G K R N O E W E B C E U E K S T Colchester R T W Hollytrees L G L R E Town Hall R H H L Museum a S E L . T T NS S L G Gc G D . b d T G Ga T STREE L . GH I I E Fd H Coach N Fa Fb Fc H pick-up R HIGH Hb KE EET points R BAL HIGH ST STREE E T Visitor N R Information E SAGE K S BANK AST Centre L CULVER ST. E PA T A B E T C EST E U W E LVER STREET E R H ST. C L CHUR T R O TRINITY STREET S T N 4 G S Ja WALK 3 ER Ed CULV N W E 1 O PRI RY E Y A W D LI ON A U R LK A Q Ec E Firstsite E J S c W H T Visual Arts Eb Colchester R AL E E Library K T Ea T WYRE STREET ALK ELD LANE SHOR SIR ISAAC’S W S EET Lift PRIORY STR T VINEYARD GATE VINEYARD ST . ROUCH STREET T C OHN’S STREE E ST. J B T O Db Da A Ca Cb T G Cd D O L A S E P T H H A ’ N Ba Af OS S W B Ae O S E R B N T L Bb u Ad E R L s S STREET Ac E ta S Bc tio Ab E T n Aa T Colchester A134 . -

English Counties

ENGLISH COUNTIES See also the Links section for additional web sites for many areas UPDATED 23/09/21 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] TRAVELINE SITES FOR ENGLAND GB National Traveline: www.traveline.info More-detailed local options: Traveline for Greater London: www.tfl.gov.uk Traveline for the North East: https://websites.durham.gov.uk/traveline/traveline- plan-your-journey.html Traveline for the South West: www.travelinesw.com Traveline for the West & East Midlands: www.travelinemidlands.co.uk Black enquiry line numbers indicate a full timetable service; red numbers imply the facility is only for general information, including requesting timetables. Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that a county or council might be showing on its web site. ENGLAND BEDFORDSHIRE BEDFORD Borough Council No publications Public Transport Team, Transport Operations Borough Hall, Cauldwell Street, Bedford MK42 9AP Tel: 01234 228337 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] www.bedford.gov.uk/transport_and_streets/public_transport.aspx COUNTY ENQUIRY LINE: 01234 228337 (0800-1730 M-Th; 0800-1700 FO) PRINCIPAL OPERATORS & ENQUIRY LINES: Grant Palmer (01525 719719); Stagecoach East (01234 220030); Uno (01707 255764) CENTRAL BEDFORDSHIRE Council No publications Public Transport, Priory House, Monks Walk Chicksands, Shefford SG17 5TQ Tel: 0300 3008078 Fax: 01234 228720 Email: [email protected] -

Bus Review Report

Item Scrutiny Panel 10 16 March 2018 Report of Assistant Director of Policy and Author Jonathan Baker Corporate 282207 Title Bus Review Wards Not applicable affected 1. Executive Summary 1.1 The Scrutiny Panel at its meeting in September 2017 agreed to review the bus services operating in Colchester. As part of this review the Panel have invited bus companies, Essex County Council and a Community Transport provider to this meeting as part of an information gathering session. 1.2 The review will follow the objectives as agreed at the September meeting. These are included below - To understand the strategic role and benefits of bus operation and how it can best serve the community. To investigate and scrutinise what bus companies are doing to; . Improve the punctuality of services . Increase bus usage . Reduce emissions . Make buses more accessible . Communicate with passengers when services are cancelled or altered. To improve the dialogue between bus companies that operate in the Borough and Colchester Borough Council, Councillors and Residents. 1.3 This meeting has been arranged following the postponement, due to severe weather, of the original bus review date in February. 1.4 Following on from the review, the Panel may wish to schedule a further discussion at an upcoming meeting to decide the next steps of the review. 2. Action Required 2.1 To undertake an information gathering session, in line with the bus review objectives prior to deciding on the next steps. 3. Reason for Scrutiny 3.1 The Panel received a request from a member of the Panel to review bus services in Colchester. -

Where to Catch Your Bus in Colchester Town Centre

Where to catch your bus in Colchester Town Centre W E S E WIL LIA M ’S WA T LK A MA Colchester Town Centre G Colchester S S E T T O I Castle D O S R Bus Stops S C T E T G K R N O E W E B C E U E K S T Colchester R T W Hollytrees L G L R E Town Hall R H H L Museum a S E L . T T NS S L G Gc G D . b d T G Ga T STREE L . GH I I E Fd H Coach N Fa Fb Fc H pick-up R HIG H KE EET H b points R BAL HIGH ST STREE E T N R E SAGE K S BANK AST L CULVER ST. E PA T A B E T C EST E UL T W E VER STREE H ST. E R CHURC L T R O TRINITY STREET S T N 4 G S Ja WALK 3 ER Ed CULV N W E 1 O PRI RY E Y A W D LI ON A U R LK A Q Ec E Firstsite E J S c W H T Visual Arts Eb Colchester R AL E E Library K T Ea T WYRE STREET ALK ELD LANE SHOR SIR ISAAC’S W S EET Lift PRIORY STR T VINEYARD GATE VINEYARD ST . STREET CROUCH OHN’S STREET E ST. J B T O Db Da A Ca Cb T G Cd D O L A S E P T H H A ’ N Ba Af OS S W B Ae O S E R B N T L Bb u Ad E R L s S STREET Ac E ta S Bc tio Ab E T n Aa T Colchester A134 . -

Notice and Proceedings for the East of England

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2385 PUBLICATION DATE: 24/07/2019 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 14/08/2019 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 31/07/2019 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online 1 NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Eastbrook Shaftesbury Road Cambridge CB2 8DR The public counter in Cambridge is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. -

Name Location Phone Publish E-Mail 24X7 Ltd

Name Location Phone Publish e-Mail 24x7 Ltd STANSTED AIRPORT 01279 661661 [email protected] 405 CAB CO LTD IPSWICH 07949078899 - 01473 405 405 [email protected] A L CARS LEISTON 01728 830044 [email protected] A1 Cars Suffolk Ltd BURY ST EDMUNDS 01284766777 [email protected] A2B Needham Market Needham Market 07944 391947 [email protected] A2B Taxis (Newmarket) Ltd Soham (01638) 750 888 [email protected] AAA Cabs Ltd Sudbury 01787868686 [email protected] Abbey Cars Bury St Edmunds 07884212436 [email protected] ABLE TAXIS Ltd DISS 01379 643033 [email protected] Acorn Taxis Thetford Thetford 01842775050 [email protected] Alan Kelly t/a Kellys cabs Needham market 07722855526 [email protected] Alan's Cars Service ltd T/A Alans Taxis Ely 01353 665050 [email protected] Albany Travel (Ipswich) Ltd Ipswich 07860338767 [email protected] ALBIES LTD GREAT YARMOUTH 01493331111 [email protected] Ali Romjan Ipswich 07702118553 [email protected] All Day Cars Bury St Edmunds 07843129008 [email protected] All Travel Services LTD Ipswich 07446222040 [email protected] Ambassador Travel (Anglia) Ltd Great Yarmouth 01493 440350 [email protected] Andalusia Trading Ltd T/A Roadrunner Taxis LOWESTOFT 01502555555 [email protected] Arrow Taxi Services Ltd Stowmarket 01449 677677 [email protected] Arrow Taxis Essex Limited Maldon 01621855111 [email protected] Aspire Together CIC Bury St Edmunds 01284 766126 [email protected] Atlas 24|7 -

2A 2 93 92 9497 98

Babergh and Essex Services 2 2A 92 93 94 97 98 695 Your guide to our bus services from Ipswich into Babergh, Essex & Tendering Bus times from Sunday 29th August 2021 2/2A Clacton | Clacton Shopping Village | Weeley | Tendring | Manningtree | Mistley Mondays to Saturdays Service Number 2A ◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2A ◆ 2◆ Clacton, Pier Avenue 0625 0830 1055 1300 1525 1735 Clacton, Rail Station 0627 0832 1057 1302 1527 1737 Clacton, Valley Road, The Range 0632 0837 1102 1307 1532 1742 Clacton, Shopping Village 0639 0844 1109 1314 1539 1749 Clacton, Lt Clacton Morrisons 0641 0846 1111 1316 1541 1751 Little Clacton, Blacksmiths Arms 0645 0850 1115 1320 1545 1755 2 Weeley, The Street 0651 0856 1121 1326 1551 1801 Tendring Heath, Hall Lane 0658 0903 1128 1333 1558 1808 Little Bentley, Bricklayers Arms — 0908 1133 1338 — 1813 Little Bromley, Post Office — 0918 1143 1348 — 1823 Lawford, Place — 0921 1146 1351 — 1826 Manningtree Rail Station — 0925 1150 1355 — 1830 Manningtree, High School — 0930 1155 1400 — 1835 Mistley Church — 0933 1158 1403 — 1838 Horsley Cross, Cross Inn 0702 — — — 1602 — Mistley Heath 0710 — — — 1610 — Mistley, Rigby Avenue 0713 0935 1200 1405 1613 1840 Code: ◆ - This journey is sponsored by Essex County Council No service on Sundays or Bank Holidays 2/2A Mistley | Manningtree | Tendring | Weeley | Clacton Shopping Village | Clacton Mondays to Saturdays Service Number 2◆ 2◆ 2A ◆ 2◆ 2◆ 2◆ Mistley, Rigby Avenue 0715 0940 1202 1410 1615 1845 Mistley Heath — — 1205 — — — Horsley Cross, Cross Inn — — 1213 — — — Mistley, Church 0718 0943 — 1413 -

Notices and Proceedings

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (EAST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2429 PUBLICATION DATE: 27/05/2020 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 17/06/2020 PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. If you wish to make an objection to an application it is recommended you send the details to [email protected]. If you have an urgent query related to dealing with coronavirus (COVID-19) response please email [email protected] with COVID-19 clearly stated in the subject line and a member of staff will contact you. If you are an existing operator without a VOL user account, and you would like one, please email [email protected] and a member of staff will contact you as soon as possible to arrange this. You will need to answer some security questions. 1 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (East of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 27/05/2020 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. -

Not for Publication by Virtue of Paragraph 8 of Part 1 of Schedule 12A to the Local Government Act 1972 (Expenditure for Acquisi

Item Scrutiny Panel 13 23 August 2016 Report of Assistant Chief Executive Author Jonathan Baker 282207 Title Questions to Bus Companies in Colchester Wards Not applicable affected Following a request at the last Scrutiny Panel meeting the Panel is invited to suggest questions to be submitted to bus companies. 1. Action required 1.1 To suggest further questions for inclusion into the letter from the Scrutiny Panel to be sent to bus operators in the Borough of Colchester. 1.2 To agree a deadline for Bus operators to respond to the letter and identify when the responses to the questions will be reviewed. 1.3 For the Scrutiny Panel to approve that the draft letter, with additional questions, be agreed by the Chairman and Group Spokespersons following the meeting. 2. Reason for scrutiny 2.1 Following a discussion at the July 2016 meeting of the Scrutiny Panel it was agreed that a list of questions would be sent to bus operators operating within the Colchester Borough Council area. 2.2 An e-mail to Scrutiny Panel members was circulated requesting questions for inclusion in the letter. A copy of the questions, with duplicates removed, has been included in the draft letter for approval. 2.3 Further questions or amendments to the letter are welcome, with a final draft being agreed by the Chairman and the Groups spokesperson prior to the letter being sent out. 2.4 The Scrutiny Panel will also need to determine a timescale for the bus operators to respond to the questions and review the responses prior to taking any further steps. -

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS (New Entries First with Older Entries Retained Underneath)

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS (new entries first with older entries retained underneath) Now go back to: Home Page Introduction or on to: The Best Timetables of the British Isles Summary of the use of the 24-hour clock Links Section English Counties Welsh Counties, Scottish Councils, Northern Ireland, Republic of Ireland, Channel Islands and Isle of Man Bus Operators in the British Isles Rail Operators in the British Isles SEPTEMBER 25 2021 – FIRST RAIL RENEWS SPONSORSHIP I am pleased to announce that First Rail (www.firstgroupplc.com/about- firstgroup/uk-rail.aspx) has renewed its sponsorship of my National Rail Passenger Operators' map and the Rail section of this site, thereby covering GWR, Hull Trains, Lumo, SWR and TransPennine Express, as well as being a partner in the Avanti West Coast franchise. This coincides with the 50th edition of the map, published today with an October date to reflect the start of Lumo operations. I am very grateful for their support – not least in that First Bus (www.firstgroupplc.com/about- firstgroup/uk-bus.aspx) is already a sponsor of this website. JULY 01 2021 – THE FIRST 2021 WELSH AUTHORITY TIMETABLE Whilst a number of authorities in SW England have produced excellent summer timetable books – indeed some produced them throughout the pandemic – for a country that relies heavily on tourism Wales is doing an utterly pathetic job, with most of the areas that used to have good books simply saying they don’t expect to publish anything until the autumn or the winter – or, indeed that they have no idea when they’ll re-start (see the entries in Welsh Counties section). -

FINAL REPORT V1.0

FINAL REPORT v1.0 DfT - TRANSPORT DIRECT Project Support & Consultancy Services Framework FareXChange Scoping Study Project Reference - TDT / 129 June 2006 Prepared By: Prepared For: Carl Bro Group Ltd, Transport Direct Bracton House Department for Transport 34-36 High Holborn Zones 1/F18 - 1/F20 LONDON WC1V6AE Ashdown House 123 Victoria Street LONDON SW1E 6DE Tel: +44 (0)20 71901697 Fax: +44 (0)20 71901698 Email: [email protected] www.carlbro.com DfT Transport Direct FareXChange Scoping Study CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY __________________________________________________ 6 1 INTRODUCTION ___________________________________________________ 10 1.1 __ What is FareXChange? _____________________________________ 10 1.2 __ Background _______________________________________________ 10 1.3 __ Scoping Study Objectives ____________________________________ 11 1.4 __ Acknowledgments __________________________________________ 11 2 CONSULTATION AND RESEARCH ___________________________________ 12 2.1 __ Who we consulted _________________________________________ 12 2.2 __ How we consulted __________________________________________ 12 2.3 __ Overview of Results ________________________________________ 12 3 THE FARE SETTING PROCESS AND THE ROLES OF INTERESTED PARTIES _____________________________________________________________ 14 3.1 __ The Actors _______________________________________________ 14 3.2 __ Fare Stages and Fares Tables ________________________________ 16 3.3 __ Flat and Zonal Fares ________________________________________ 17 -

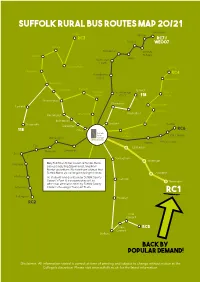

Suffolk Rural Bus Routes Map 20/21

suffolk rural Bus Routes Map 20/21 Felixstowe Leiston Walton RC3 rC7 / Trimley WE007 Kelsale Bucklesham Trimley Yoxford St Mary Kirton Martlesham Heath Saxmundham Harwich Peasenhall RC4 Woodbridge (SCC) Dovercourt Badingham Dennington Parham Ipswich Wickham Grundisburgh Horsley Market (SCC) 118 Cross Framlingham Witnesham Manningtree Laxfield Lawford Westerfield Kettleburgh Charsfield Brandeston Stradbroke Swilland Ardleigh Clacton Cretingham rC6 118 Otley Capel St Mary Little Clacton Rishangles Weeley Weeley Heath Eye Colchester Thorndon Debenham Diss Sproughton Wivenhoe Palgrave Bury St Edmunds bus station to Suffolk Rural, pick-ups including Stowmarket, Needham Market and others: We have been advised that Suffolk Norse are no longer running this route. Alresford Wortham All students who qualify under Suffolk County Hadleigh Council’s Post-16 transport policy will be Thorrington offered an alternative route by Suffolk County Botesdale Council’s Passenger Transport Team. RC1 Rickinghall Polstead rC2 Little Cornard Great rC5 Cornard Sudbury BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! Disclaimer: All information stated is correct at time of printing and subject to change without notice at the College’s discretion. Please visit www.suffolk.ac.uk for the latest information. Suffolk Rural Transport Guide 2020/21 Otley College is set for a new future after changing its name during a merger with Ipswich-based Suffolk New College. The former Otley College, first opened in 1970, has now become Suffolk Rural as of 1 January 2020. Travelling to Suffolk Rural Getting to Suffolk Rural is easy. There is an extensive network of direct bus routes from across Suffolk and Essex. Suffolk County Council Transport For routes 116, 118 and WE007 (Woodbridge onwards) you can apply to Suffolk County Council for a discretionary travel pass (16-18 Specialist Transport year olds only).