CLAY-THESIS.Pdf (1.531Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I'm Gonna Keep Growin'

always bugged off of that like he always [imi tated] two people. I liked the way he freaked that. So on "Gimme The Loot" I really wanted to make people think that it was a different person [rhyming with me]. I just wanted to make a hot joint that sounded like two nig gas-a big nigga and a Iii ' nigga. And I know it worked because niggas asked me like, "Yo , who did you do 'Gimme The Loot' wit'?" So I be like, "Yeah, well, my job is done." I just got it from Slick though. And Redman did it too, but he didn't change his voice. What is the illest line that you ever heard? Damn ... I heard some crazy shit, dog. I would have to pick somethin' from my shit, though. 'Cause I know I done said some of the most illest rhymes, you know what I'm sayin'? But mad niggas said different shit, though. I like that shit [Keith] Murray said [on "Sychosymatic"]: "Yo E, this might be my last album son/'Cause niggas tryin' to play us like crumbs/Nobodys/ I'm a fuck around and murder everybody." I love that line. There's shit that G Rap done said. And Meth [on "Protect Ya Neck"]: "The smoke from the lyrical blunt make me ugh." Shit like that. I look for shit like that in rhymes. Niggas can just come up with that one Iii' piece. Like XXL: You've got the number-one spot on me chang in' the song, we just edited it. -

BLUETONES! O L

The Weekly Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus Are you worried at all about coming to America to try and find success? SM: I think if you go anywhere, you go open-minded just to see what the people are like. You don’t go with preconceptions. I think we’re just waiting. We’re waiting for when there’s a demand and when people do actually want to go and see us. I’m talking about the fans. _ How would you describe your music to someone from California? EC: It’s rock ’n’ roll, really. The Bluetones are a band from Houndslow, England, which, in case your English SM: Melodic guitar rock. Pop music. We’re influenced by a lot of West Coast Ameri geography is not up to par, is near Heathrow Airport in London. This fine quartet, com can stuff from the ’60s— Crosby, Stills & Nash, Buffet, The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield. prised of singer/lyricist Mark Morriss, bassist Scott Morriss, drummer Eds Chesters Do you see yourself as a primarily English band? and guitarist Adam Devlin, gets my vote for the best new pop band out of Britain. SM: We don’t like flying flags in foreign countries or anything. That’s a load of rub They’ve honed their skills on tour with the likes of Supergrass, while the less talented bish. The thing that’s happening is that they’re trying to promote “Britpop” in America scruffs got all the attention. right now. However, in January, the hounds were released in the form of the Bluetones’ first EC: It’s bollocks. -

Cue Point Aesthetics: the Performing Disc Jockey In

CUE POINT AESTHETICS: THE PERFORMING DISC JOCKEY IN POSTMODERN DJ CULTURE By Benjamin De Ocampo Andres A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Sociology Committee Membership Dr. Jennifer Eichstedt, Committee Chair Dr. Renee Byrd, Committee Member Dr. Meredith Williams, Committee Member Dr. Meredith Williams, Graduate Coordinator May 2016 ABSTRACT CUE POINT AESTHETICS: THE PERFORMING DISC JOCKEY IN POSTMODERN DJ CULTURE Benjamin De Ocampo Andres This qualitative research explores how social relations and intersections of popular culture, technology, and gender present in performance DJing. The methods used were interviews with performing disc jockeys, observations at various bars, and live music venues. Interviews include both women and men from varying ages and racial/ethnic groups. Cultural studies/popular culture approaches are utilized as the theoretical framework, with the aid of concepts including resistance, hegemony, power, and subcultures. Results show difference of DJ preference between analog and digital formats. Gender differences are evident in performing DJ's experiences on and off the field due to patriarchy in the DJ scene. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and Foremost, I would like to thank my parents and immediate family for their unconditional support and love. You guys have always come through in a jam and given up a lot for me, big up. To "the fams" in Humboldt, you know who you are, thank you so much for holding me down when the time came to move to Arcata, and for being brothers from other mothers. A shout out to Burke Zen for all the jokes cracked, and cigarettes smoked, at "Chinatown." You help get me through this and I would have lost it along time ago. -

*5 ¡£ ¡¡¡Bis MCC Lounge 10 P J

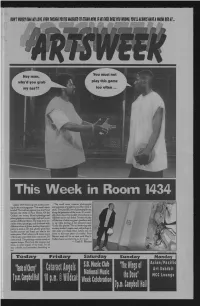

mummttmna. p j This Week in Room 1434 Gallery 1434 dishes up yet another serv The small room contains photographs ing for the art-hungry eye. This week’s show and paintings of spaghetti and other types of is titled “Not with my spatula you don’t" and pasta. Two parallel rows o f photographs run features the work of Paco Shima. O f the along the perimeter o f the room. It's a verit Gallery’s two rooms, Shima’s paintings and able photo sh oot fo r noodles w hen shown in photographs are center stage, and each room different sauces and dishes. It seems to play carries a different theme. The large room in off the idea of what my great-grandma used cludes several paintings, each bordered with to say when looking at her prepared meal: different colon of glitter, making them quite “Looks like picture.” It’s an interesting take pretty to look at. It’s this glittery glory that on every student’s staple m eal, and perhaps it catches your eye and forces you take in the will make you think twice before you sit entire piece. That’s when you’ll realize many down to that next plate of noodles. Paco of them also come with their own scents. It’s Shima’s work m il be on view until May 8. a nice touch. The paintings consist mostly of Gallery hours are from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. organic shapes. They look like tongues and — Tami T . Mnoian liven, or other organs of the body. -

Music and the Construction of Historical Narrative in 20Th and 21St Century African-American Literature

1 Orientations in Time: Music and the Construction of Historical Narrative in 20th and 21st Century African-American Literature Leisl Sackschewsky A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Sonnet Retman, Chair Habiba Ibrahim Alys Weinbaum Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English 2 © Copyright 2016 Leisl Sackschewsky 3 University of Washington Abstract Orientations in Time: Music and the Construction of Historical Narrative in 20th and 21st Century African-American Literature Chair of Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Sonnet Retman American Ethnic Studies This dissertation argues that the intersections between African-American literature and music have been influential in both the development of hip-hop aesthetics and, specifically, their communication of historical narrative. Challenging hip-hop historiographers that narrate the movement as the materialization of a “phantom aesthetic”, or a sociological, cultural, technological, and musical innovation of the last forty years, this dissertation asserts that hip-hop artists deploy distinctly literary techniques in their attempts to animate, write, rewrite, rupture, or reclaim the past for the present. Through an analysis of 20th and 21st century African-American literary engagements with black music, musical figures, scenes of musical performance, and what I call ‘musical-oral’, I hope to demonstrate how prose representations of music disrupt the linear narratives of -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

It's Jerry's Birthday Chatham County Line

K k JULY 2014 VOL. 26 #7 H WOWHALL.ORG KWOW HALL NOTESK g k IT’S JERRY’S BIRTHDAY On Friday, August 1, KLCC and Dead Air present an evening to celebrate Jerry Garcia featuring two full sets by the Garcia Birthday Band. Jerry Garcia, famed lead guitarist, songwriter and singer for The Grateful Dead and the Jerry Garcia Band, among others, was born on August 1, 1941 in San Francisco, CA. Dead.net has this to say: “As lead guitarist in a rock environment, Jerry Garcia naturally got a lot of attention. But it was his warm, charismatic personality that earned him the affection of millions of Dead Heads. He picked up the guitar at the age of 15, played a little ‘50s rock and roll, then moved into the folk acoustic guitar era before becoming a bluegrass banjo player. Impressed by The Beatles and Stones, he and his friends formed a rock band called the Warlocks in late 1964 and debuted in 1965. As the band evolved from being blues-oriented to psychedelic/experi- mental to adding country and folk influences, his guitar stayed out front. His songwriting partnership with Robert Hunter led to many of the band’s most memorable songs, including “Dark Star”, “Uncle John’s Band” and the group’s only Top 10 hit, “Touch of Grey”. Over the years he was married three times and fathered four daughters. He died of a heart attack CHATHAM COUNTY LINE in 1995.” On Sunday, July 27, the Community Tightrope also marks a return to Sound Fans have kept the spirit of Jerry Garcia alive in their hearts, and have spread the spirit Center for the Performing Arts proudly wel- Pure Studios in Durham, NC, where the and the music to new generations. -

Three Solitudes and a DJ: a Mashed-Up Study of Counterpoint in a Digital Realm

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-26-2013 12:00 AM Three Solitudes and a DJ: A Mashed-up Study of Counterpoint in a Digital Realm Anthony B. Cushing The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Norma Coates The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Anthony B. Cushing 2013 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Cushing, Anthony B., "Three Solitudes and a DJ: A Mashed-up Study of Counterpoint in a Digital Realm" (2013). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 1229. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/1229 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THREE SOLITUDES AND A DJ: A MASHED-UP STUDY OF COUNTERPOINT IN A DIGITAL REALM (Thesis format: Monograph) by Anthony B. Cushing Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Anthony Cushing 2013 ii Abstract This dissertation is primarily concerned with developing an understanding of how the use of pre-recorded digital audio shapes and augments conventional notions of counterpoint. It outlines a theoretical framework for analyzing the contrapuntal elements in electronically and digitally composed musics, specifically music mashups, and Glenn Gould’s Solitude Trilogy ‘contrapuntal radio’ works. -

Williams, Justin A. (2010) Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop Music: Theoretical Frameworks and Case Studies

Williams, Justin A. (2010) Musical borrowing in hip-hop music: theoretical frameworks and case studies. PhD thesis, University of Nottingham. Access from the University of Nottingham repository: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/11081/1/JustinWilliams_PhDfinal.pdf Copyright and reuse: The Nottingham ePrints service makes this work by researchers of the University of Nottingham available open access under the following conditions. · Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. · To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in Nottingham ePrints has been checked for eligibility before being made available. · Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not- for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. · Quotations or similar reproductions must be sufficiently acknowledged. Please see our full end user licence at: http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/end_user_agreement.pdf A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the repository url above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact [email protected] MUSICAL BORROWING IN HIP-HOP MUSIC: THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS AND CASE STUDIES Justin A. -

Dj Drama Mixtape Mp3 Download

1 / 2 Dj Drama Mixtape Mp3 Download ... into the possibility of developing advertising- supported music download services. ... prior to the Daytona 500. continued on »p8 No More Drama Will mixtape bust hurt hip-hop? ... Highway Companion Auto makers embrace MP3 Barsuk Backed Something ... DJ Drama's Bust Leaves Future Of The high-profile police raid.. Download Latest Dj Drama 2021 Songs, Albums & Mixtapes From The Stables Of The Best Dj Drama Download Website ZAMUSIC.. MP3 downloads (160/320). Lossless ... SoundClick fee (single/album). 15% ... 0%. Upload limits. Number of tracks. Unlimited. Unlimited. Unlimited. MP3 file.. Dec 14, 2020 — Bad Boy Mixtape Vol.4- DJ S S(1996)-mf- : Free Download. Free Romantic Music MP3 Download Instrumental - Pixabay. Lil Wayne DJ Drama .... On this special episode, Mr. Thanksgiving DJ Drama leader of the Gangsta Grillz movement breaks down how he changed the mixtape game! He's dropped .. Apr 16, 2021 — DJ Drama, Jacquees – ”QueMix 4′ MP3 DOWNLOAD. DJ Drama, Jacquees – ”QueMix 4′: DJ Drama join forces tithe music sensation .... Download The Dedication Lil Wayne MP3 · Lil Wayne:Dedication 2 (Full Mixtape)... · Lil Wayne - Dedication [Dedication]... · Dedicate... · Lil Wayne Feat. DJ Drama - .... Dj Drama Songs Download- Listen to Dj Drama songs MP3 free online. Play Dj Drama hit new songs and download Dj Drama MP3 songs and music album ... best blogs for downloading music, The Best of Music For Content Creators and ... SMASH THE CLUB | DJ Blog, Music Blog, EDM Blog, Trap Blog, DJ Mp3 Pool, Remixes, Edits, ... Dec 18, 2020 · blog Mix Blog Studio: The Good Kind of Drama.. Juelz Santana. -

Underground Rap Albums 90S Downloads Underground Rap Albums 90S Downloads

underground rap albums 90s downloads Underground rap albums 90s downloads. 24/7Mixtapes was founded by knowledgeable business professionals with the main goal of providing a simple yet powerful website for mixtape enthusiasts from all over the world. Email: [email protected] Latest Mixtapes. Featured Mixtapes. What You Get With Us. Fast and reliable access to our services via our high end servers. Unlimited mixtape downloads/streaming in our members area. Safe and secure payment methods. © 2021 24/7 Mixtapes, Inc. All rights reserved. Mixtape content is provided for promotional use and not for sale. The Top 100 Hip-Hop Albums of the ’90s: 1990-1994. As recently documented by NPR, 1993 proved to be an important — nay, essential — year for hip-hop. It was the year that saw 2Pac become an icon, Biz Markie entangled in a precedent-setting sample lawsuit, and the rise of the Wu-Tang Clan. Indeed, there are few other years in hip- hop history that have borne witness to so many important releases or events, save for 1983, in which rap powerhouse Def Jam was founded in Russell Simmons’ dorm room, or 1988, which saw the release of about a dozen or so game-changing releases. So this got us thinking: Is there really a best year for hip-hop? As Treble’s writers debated and deliberated, we came up with a few different answers, mostly in the forms of blocks of four or five years each. But there was one thing they all had in common: they were all in the 1990s. Now, some of this can be chalked up to age — most of Treble’s staff and contributors were born in the 1980s, and cut their musical teeth in the 1990s. -

Fascicule S4E5 Mai/Juin 2015 (Pdf, 7095Ko)

à découper et à mettre sur son frigo son sur à mettre et à découper AGENDA DE FRIGO AU DOS AU FRIGO DE AGENDA SOMMAIRE Agenda de Frigo................. 2 Edito.................................... 3 Le programme.................... 5 Le poster de Terreur Graphique............... 32 Les actions culturelles........ 34 Le centre ressource............ 37 Le coin des studios.................38 L’instant scientifique...............40 La fiche utile du Docteur Fred.................. 42 Rewind................................. 51 Chez les copains................; 63 Les infos très pratiques du Temps Machine................64 AGENDA DE FRIGO LE TEMPS MACHINE CooRdonnées EDITO Le Temps Machine Parvis Miles Davis BP 134 37301 JOUÉ-LÈS-TOURS CEDEX Tel : 02 47 48 90 60 Courriel : [email protected] www.letempsmachine.com www.facebook.com/letempsmachine DANS LES FAITS ! Horaires Les Bureaux Du lundi au vendredi : Le Temps Machine - l’Espace Musiques murs l’actualité musicale et l’avant-garde, nous 10h00 / 12h30 & 14h00 / 18h00 LE Centre Actuelles de l’Agglomération de Tours - s’inscrit changerons d’atmosphère. Du mardi au vendredi : 10h00 / 13h00 et 14h00 / 18h00 dans le réseau d’une ville, d’un territoire. Il Samedi (uniquement quand concert le soir) : 14h00 / 17h00 Dans les faits ! En juin. Place à un laboratoire ; est destiné au plus grand nombre, ouvert à Et les soirs de concerts de 20h30 à 21h30 à ciel ouvert. Quand les beaux jours arrivent, Les soirs de concerts tous, s’adresse à tous, se construit et s’alimente Ouverture du bar : 20h30 comme vous, Le Temps Machine a des envies Ouverture de la billetterie : 20h30 par l’action de tous. Nos missions d’intérêt d’évasion.