Coral Reef Benthic Monitoring Final Report / Workshop Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experimental Study of Nearshore Dynamics on a Barred Beach with Rip Channels Merrick C

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 107, NO. C6, 3061, 10.1029/2001JC000955, 2002 Experimental study of nearshore dynamics on a barred beach with rip channels Merrick C. Haller1 Cooperative Institute for Limnology and Ecosystems Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA Robert A. Dalrymple and Ib A. Svendsen Center for Applied Coastal Research, University of Delaware, Newark, Delaware, USA Received 4 May 2001; revised 17 October 2001; accepted 6 November 2001; published 28 June 2002. [ 1 ] Wave and current measurements are presented from a set of laboratory experiments performed on a fixed barred beach with periodically spaced rip channels using a range of incident wave conditions. The data demonstrate that the presence of gaps in otherwise longshore uniform bars dominates the nearshore circulation system for the incident wave conditions considered. For example, nonzero cross-shore flow and the presence of longshore pressure gradients, both resulting from the presence of rip channels, are not restricted to the immediate vicinity of the channels but instead are found to span almost the entire length of the longshore bars. In addition, the combination of breaker type and location is the dominant driving mechanism of the nearshore flow, and both are found to be strongly influenced by the variable bathymetry and the presence of a strong rip current. The depth-averaged currents are calculated from the measured velocities assuming conservation of mass across the measurement grid. The terms in both the cross-shore and longshore momentum balances are calculated, and their relative magnitudes are quantified. The cross-shore balance is shown to be dominated by the cross-shore pressure and radiation stress gradients in general agreement with previous results, however, the rip current is shown to influence the wave breaking and the wave-induced setup in the rip channel. -

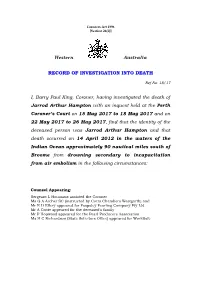

Inquest Finding

Coroners Act 1996 [Section 26(1)] Western Australia RECORD OF INVESTIGATION INTO DEATH Ref No: 18/17 I, Barry Paul King, Coroner, having investigated the death of Jarrod Arthur Hampton with an inquest held at the Perth Coroner’s Court on 15 May 2017 to 18 May 2017 and on 22 May 2017 to 26 May 2017, find that the identity of the deceased person was Jarrod Arthur Hampton and that death occurred on 14 April 2012 in the waters of the Indian Ocean approximately 90 nautical miles south of Broome from drowning secondary to incapacitation from air embolism in the following circumstances: Counsel Appearing: Sergeant L Housiaux assisted the Coroner Ms G A Archer SC (instructed by Corrs Chambers Westgarth) and Mr N D Ellery appeared for Paspaley Pearling Company Pty Ltd Mr A Coote appeared for the deceased’s family Mr P Hopwood appeared for the Pearl Producers Association Ms H C Richardson (State Solicitors Office) appeared for WorkSafe Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 2 THE EVIDENCE ................................................................................................................ 4 THE DECEASED ............................................................................................................... 8 THE DECEASED’S DIVING BACKGROUND ....................................................................... 9 THE DECEASED’S SHOULDER AND PECTORALIS MAJOR .............................................. 10 THE DECEASED JOINS -

Climate Change Impacts on Corals in the UK Overseas Territories of British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) and the Pitcairn Islands

Climate change impacts on corals in the UK Overseas Territories of British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) and the Pitcairn Islands Blue Belt Programme April 2021 Authors: Lincoln, S., Cowburn, B., Howes, E., Birchenough, S.N.R., Pinnegar, J., Dye, S., Buckley, P., Engelhard, G.H. and Townhill, B.L. Issue date: 29 March 2021 © Crown copyright 2020 This information is licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications www.cefas.co.uk Document Control Submitted to: Kylie Bamford (UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office) Date submitted: 29 March 2021 Project Manager: Victoria Young Report compiled by: Susana Lincoln Quality control by: Georg H. Engelhard Approved by and date: Christopher Darby and Silvana Birchenough, 25 March 2021 Version: Final checked Version Control History Author Date Summary of changes Version Lincoln et al. November 2020 Initial draft V0.1 Lincoln et al. January 2021 External peer review completed V0.2 Lincoln et al. February 2021 QC QA corrections and final draft V1.0 Lincoln et al. February 2021 Comments from Emily Hardman V1.1 (Marine Management Organisation) Lincoln et al. March 2021 Editorial comments from Silvana V2.0 Birchenough et al. Lincoln et al. March 2021 Editorial comments from V2.1 Christopher Darby Lincoln et al. March 2021 All comments addressed Final Lincoln et al. April 2021 Final checks by reviewers prior Checked to publication This report has been reviewed by: Sheppard, C. (University of Warwick, UK), Wabnitz, C. -

Maiana Social and Economic Report 2008

M AIANA ISLAND 2008 SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE PRODUCED BY THE MINISTRY OF INTERNAL AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS, WITH FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE UNITED NATION DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM, AND TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FROM THE SECRETARIAT OF THE PACIFIC COMMUNITY. Strengthening Decentralized Governance in Kiribati Project P.O. Box 75, Bairiki, Tarawa, Republic of Kiribati Telephone (686) 22741 or 22040, Fax: (686) 21133 MAIANA ANTHEM MAIANA I TANGIRIKO MAIANA I LOVE YOU Maiana I tangiriko - 2 - FOREWORD by the Honourable Amberoti Nikora, Minister of Internal and Social Affairs, July, 2007 I am honored to have this opportunity to introduce this revised and updated socio-economic profile for Maiana island. The completion of this profile is the culmination of months of hard-work and collaborative effort of many people, Government agencies and development partners particularly those who have provided direct financial and technical assistance towards this important exercise. The socio-economic profiles contain specific data and information about individual islands that are not only interesting to read, but more importantly, useful for education, planning and decision making. The profile is meant to be used as a reference material for leaders both at the island and national level, to enable them to make informed decisions that are founded on accurate and easily accessible statistics. With our limited natural and financial resources it is very important that our leaders are in a position to make wise decisions regarding the use of these limited resources, so that they are targeted at the most urgent needs and produce maximum impact. In addition, this profile will act as reference material that could be used for educational purposes, at the secondary and tertiary levels. -

Checklist of Fish and Invertebrates Listed in the CITES Appendices

JOINTS NATURE \=^ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Checklist of fish and mvertebrates Usted in the CITES appendices JNCC REPORT (SSN0963-«OStl JOINT NATURE CONSERVATION COMMITTEE Report distribution Report Number: No. 238 Contract Number/JNCC project number: F7 1-12-332 Date received: 9 June 1995 Report tide: Checklist of fish and invertebrates listed in the CITES appendices Contract tide: Revised Checklists of CITES species database Contractor: World Conservation Monitoring Centre 219 Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 ODL Comments: A further fish and invertebrate edition in the Checklist series begun by NCC in 1979, revised and brought up to date with current CITES listings Restrictions: Distribution: JNCC report collection 2 copies Nature Conservancy Council for England, HQ, Library 1 copy Scottish Natural Heritage, HQ, Library 1 copy Countryside Council for Wales, HQ, Library 1 copy A T Smail, Copyright Libraries Agent, 100 Euston Road, London, NWl 2HQ 5 copies British Library, Legal Deposit Office, Boston Spa, Wetherby, West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ 1 copy Chadwick-Healey Ltd, Cambridge Place, Cambridge, CB2 INR 1 copy BIOSIS UK, Garforth House, 54 Michlegate, York, YOl ILF 1 copy CITES Management and Scientific Authorities of EC Member States total 30 copies CITES Authorities, UK Dependencies total 13 copies CITES Secretariat 5 copies CITES Animals Committee chairman 1 copy European Commission DG Xl/D/2 1 copy World Conservation Monitoring Centre 20 copies TRAFFIC International 5 copies Animal Quarantine Station, Heathrow 1 copy Department of the Environment (GWD) 5 copies Foreign & Commonwealth Office (ESED) 1 copy HM Customs & Excise 3 copies M Bradley Taylor (ACPO) 1 copy ^\(\\ Joint Nature Conservation Committee Report No. -

Catalogue Customer-Product

AQUATIC DESIGN CENTRE 26 Zennor Trade Park Balham ¦ London ¦ SW12 0PS Shop Enquiries Tel: 020 7580 6764 Email: [email protected] PLEASE CALL TO CHECK AVAILABILITY ON DAY In Stock Yes/No Marine Invertebrates and Corals Anemones Common name Scientific name Atlantic Anemone Condylactis gigantea Atlantic Anemone - Pink Condylactis gigantea Beadlet Anemone - Red Actinea equina Y Bubble Anemone - Coloured Entacmaea quadricolor Y Bubble Anemone - Common Entacmaea quadricolor Bubble Anemone - Red Entacmaea quadricolor Caribbean Anemone Condylactis spp. Y Carpet Anemone - Coloured Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Common Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard Blue Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard Common Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard Green Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard Red Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Hard White Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - Mini Maxi Stichodactyla tapetum Carpet Anemone - Soft Blue Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Common Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Green Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Purple Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Red Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft White Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Soft Yellow Stichodactyla gigantea Carpet Anemone - Striped Stichodactyla haddoni Carpet Anemone - White Stichodactyla haddoni Curly Q Anemone Bartholomea annulata Flower Anemone - White/Green/Red Epicystis crucifer Malu Anemone - Common Heteractis crispa Malu Anemone - Pink Heteractis -

Kiribati Fourth National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity

KIRIBATI FOURTH NATIONAL REPORT TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Aranuka Island (Gilbert Group) Picture by: Raitiata Cati Prepared by: Environment and Conservation Division - MELAD 20 th September 2010 1 Contents Acknowledgement ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: OVERVIEW OF BIODIVERSITY, STATUS, TRENDS AND THREATS .................................................... 8 1.1 Geography and geological setting of Kiribati ......................................................................................... 8 1.2 Climate ................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.3 Status of Biodiversity ........................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.1 Soil ................................................................................................................................................. 12 1.3.2 Water Resources .......................................................................................................................... -

Participatory Diagnosis of Coastal Fisheries for North Tarawa And

Photo credit: Front cover, Aurélie Delisle/ANCORS Aurélie cover, Front credit: Photo Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati Authors Aurélie Delisle, Ben Namakin, Tarateiti Uriam, Brooke Campbell and Quentin Hanich Citation This publication should be cited as: Delisle A, Namakin B, Uriam T, Campbell B and Hanich Q. 2016. Participatory diagnosis of coastal fisheries for North Tarawa and Butaritari island communities in the Republic of Kiribati. Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish. Program Report: 2016-24. Acknowledgments We would like to thank the financial contribution of the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research through project FIS/2012/074. We would also like to thank the staff from the Secretariat of the Pacific Community and WorldFish for their support. A special thank you goes out to staff of the Kiribati’s Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources Development, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Environment, Land and Agricultural Development and to members of the five pilot Community-Based Fisheries Management (CBFM) communities in Kiribati. 2 Contents Executive summary 4 Introduction 5 Methods 9 Diagnosis 12 Summary and entry points for CBFM 36 Notes 38 References 39 Appendices 42 3 Executive summary In support of the Kiribati National Fisheries Policy 2013–2025, the ACIAR project FIS/2012/074 Improving Community-Based -

Ecological and Socio-Economic Impacts of Dive

ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF DIVE AND SNORKEL TOURISM IN ST. LUCIA, WEST INDIES Nola H. L. Barker Thesis submittedfor the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science Environment Department University of York August 2003 Abstract Coral reefsprovide many servicesand are a valuableresource, particularly for tourism, yet they are suffering significant degradationand pollution worldwide. To managereef tourism effectively a greaterunderstanding is neededof reef ecological processesand the impactsthat tourist activities haveon them. This study explores the impact of divers and snorkelerson the reefs of St. Lucia, West Indies, and how the reef environmentaffects tourists' perceptionsand experiencesof them. Observationsof divers and snorkelersrevealed that their impact on the reefs followed certainpatterns and could be predictedfrom individuals', site and dive characteristics.Camera use, night diving and shorediving were correlatedwith higher levels of diver damage.Briefings by dive leadersalone did not reducetourist contactswith the reef but interventiondid. Interviewswith tourists revealedthat many choseto visit St. Lucia becauseof its marineprotected area. Certain site attributes,especially marine life, affectedtourists' experiencesand overall enjoyment of reefs.Tourists were not alwaysable to correctly ascertainabundance of marine life or sedimentpollution but they were sensitiveto, and disliked seeingdamaged coral, poor underwatervisibility, garbageand other tourists damagingthe reef. Some tourists found sitesto be -

The Dietary Preferences, Depth Range and Size of the Crown of Thorns Starfish (Acanthaster Spp.) on the Coral Reefs of Koh Tao, Thailand by Leon B

The dietary preferences, depth range and size of the Crown of Thorns Starfish (Acanthaster spp.) on the coral reefs of Koh Tao, Thailand By Leon B. Haines Author: Leon Haines 940205001 Supervisors: New Heaven Reef Conservation Program: Chad Scott Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences: Peter Hofman 29/09/2015 The dietary preferences, depth range and size of the Crown of Thorns Starfish (Acanthaster spp.) on the coral reefs of Koh Tao, Thailand Author: Leon Haines 940205001 Supervisors: New Heaven Reef Conservation Program: Chad Scott Van Hall Larenstein University of Applied Sciences: Peter Hofman 29/09/2015 Cover image:(NHRCP, 2015) 2 Preface This paper is written in light of my 3rd year project based internship of Integrated Coastal Zone management major marine biology at the Van Hall Larenstein University of applied science. My internship took place at the New Heaven Reef Conservation Program on the island of Koh Tao, Thailand. During my internship I performed a study on the corallivorous Crown of Thorns starfish, which is threatening the coral reefs of Koh Tao due to high density ‘outbreaks’. Understanding the biology of this threat is vital for developing effective conservation strategies to protect the vulnerable reefs on which the islands environment, community and economy rely. Very special thanks to Chad Scott, program director of the New Heaven Reef Conservation program, for supervising and helping me make this possible. Thanks to Devrim Zahir. Thanks to the New Heaven Reef Conservation team; Ploy, Pau, Rahul and Spencer. Thanks to my supervisor at Van Hall Larenstein; Peter Hofman. 3 Abstract Acanthaster is a specialized coral-feeder and feeds nearly solely, 90-95%, on sleractinia (reef building corals), preferably Acroporidae and Pocilloporidae families. -

3. Technical Divemaster

TDI Standards and Procedures Part 3: TDI Leadership Standards 3. Technical Divemaster 3.1 Introduction This program is designed to develop the skills and knowledge necessary for an individual to lead certified technical divers in the open water environment. 3.2 Qualifications of Graduates Upon successful completion of this course, graduates may: 1. Assist an active TDI Instructor during approved diving courses provided the activities are similar to the graduate’s prior training 2. Supervise and conduct dives for certified technical divers provided the activities are similar to the graduate’s prior training 3. This program does not cover overhead environment with the exception of advanced wreck 3.3 Who May Teach 1. Any active TDI Instructor may teach this program 3.4 Student to Instructor Ratio Academic 1. Unlimited, so long as adequate facility, supplies and time are provided to ensure comprehensive and complete training of subject matter Confined Water (swimming pool-like conditions) 1. N/A Open Water (ocean, lake, quarry, spring, river or estuary) 1. A maximum of 4 students per instructor; it is the instructor’s discretion to reduce this number as conditions dictate Version 0221 33 TDI Standards and Procedures Part 3: TDI Leadership Standards 3.5 Student Prerequisites 1. Minimum age 18 2. Certified as an SDI Divemaster (equivalent ratings from other agencies are not accepted for this TDI Divemaster prerequisite) Must have all current SDI Divemaster materials 3. Provide copies of current CPR and first aid training 4. Have a current medical examination 5. Provide proof of 50 logged dives 6. Certified as a technical diver 3.6 Course Structure and Duration Open Water Execution 1. -

Love the Oceans Dive Policy Standards and Procedures

LOVE THE OCEANS DIVE POLICY STANDARDS AND PROCEDURES CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Definition of a dive 1 2. Love The Oceans Dive Standards 1 2.1 Maximum bottom time 1 2.2 Maximum depth 2 2.3 Air requirements 2 2.4 Safety stops 2 2.5 Surface interval 2 2.6 Repetitive diving 2 2.7 Flying after diving 3 2.8 Over-profiling 3 2.9 Supervision 3 2.10 PADI training courses 3 2.11 All course dives and snorkels 4 2.12 All non-course and non-training dives and snorkels 4 3. Love The Oceans Dive Procedures 4 3.1 General dive and boat procedures 5 3.2 Emergency procedures 5 3.3 Missing diver procedures 6 3.4 Injured diver procedures 6 3.5 Boat recall procedures 6 4. Dive equipment requirements 6 4.1 PADI dive training 6 4.2 Certified divers/science staff volunteers 6 5. Required safety equipment 7 6. Definitions of Roles and Responsibilities 7 6.1 Dive Operations Manager 7 6.2 Dive instructors 8 6.3 Divemasters and Dive leaders 8 6.4 Certified divers and science staff volunteers 8 7. Insurance 9 8. Night dive specific standards and protocols 9 9. Environmental Awareness 10 9.1 Code of Conduct for Whale Shark Encounters 10 9.2 Code of Conduct for Manta Ray Encounters 10 9.3 Code of Conduct for Humpback Whale Encounters 11 9.4 General Code of Conduct for Diving 12 These dive policy standards and procedures were last reviewed on 21st February 2019 1 1.