THE STATE of SOUTH CAROLINA in the Supreme Court in the Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/28/2021 Page No: 1 Master Docket by Bondsman Bondsman: a BONDING COMPANY

Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/28/2021 Page No: 1 Master Docket By Bondsman Bondsman: A BONDING COMPANY Docket #: 1768727 Defendant: LEE , KAITLIN M Charge: DRUGS GENERAL CATEGORY FOR RESALE Trial Date: 09/28/2021 1:30 PM Tuesday Court Room: 4 Presiding Judge: SELL, CHRISTINE MAHN Division: 1 Bond Amount: $12,500.00 Docket #: 1846317 Defendant: SMALL II, AARON CLAY Charge: DRIVING UNDER THE INFLUENCE Trial Date: 09/28/2021 8:30 AM Tuesday Court Room: 4 Presiding Judge: SELL, CHRISTINE MAHN Division: 1 Bond Amount: $2,000.00 Docket #: 1847417 Defendant: MIEDANER , MICHAEL R Charge: DRIVING UNDER THE INFLUENCE Trial Date: 09/28/2021 8:30 AM Tuesday Court Room: 3 Presiding Judge: STATOM, LILA Division: 4 Bond Amount: $2,500.00 Docket #: 1847003 Defendant: SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK Charge: DRIVING UNDER THE INFLUENCE Trial Date: 09/29/2021 8:30 AM Wednesday Court Room: 3 Presiding Judge: STATOM, LILA Division: 4 Bond Amount: $1,500.00 Docket #: 1847004 Defendant: SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK Charge: RESISTING ARREST OR OBSTRUCTION OF LEGAL PROCESS Trial Date: 09/29/2021 8:30 AM Wednesday Court Room: 3 Presiding Judge: STATOM, LILA Division: 4 Bond Amount: $1,000.00 Docket #: 1847006 Defendant: SCHREINER , ANDREW MARK Charge: IMPLIED CONSENT LAW - DRIVERS Trial Date: 09/29/2021 8:30 AM Wednesday Court Room: 3 Presiding Judge: STATOM, LILA Division: 4 Bond Amount: $500.00 arGS_Calendar_By_Bondsman Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/28/2021 Page No: 2 Master Docket By Bondsman Bondsman: A FREE-MAN -

Criminal-Law-Procedure

CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE I. Introduction The eight major sources of Tennessee criminal law and procedure are the Tennessee Constitution, Tennessee Code Annotated, Supreme Court Rules, Court of Criminal Appeals Rules, Rules of Evidence, Rules of Appellate Procedure, Rules of Criminal Procedure, and case law. II. Tennessee Constitution The Tennessee Constitution is, of course, the supreme source of legal authority for Tennessee’s entire criminal justice system. Some state constitutions are interpreted entirely in lockstep with the federal constitution’s analogous provisions. However, a state supreme court may interpret its own constitution’s provisions as providing greater rights to its citizens than those granted by the U.S. Constitution. The Tennessee Supreme Court has historically interpreted the Tennessee Constitution as providing greater rights than the U.S. Constitution, but the distinctions between the state and federal constitutions have dwindled in recent years. Whether the same or different from federal law, the Tennessee Constitution includes provisions affecting indictment, the right to a jury trial, search and seizure, due process and double jeopardy, the rights to confrontation and against self- incrimination, ex post facto laws, and bail. The state constitution also sets forth certain victims’ rights. A. Indictment 1. Article I, section 14 of the Tennessee Constitution guarantees that every person be charged by presentment, indictment, or impeachment. Impeachment is the extremely rare circumstance in which the legislature—rather than the grand jury—brings criminal charges against a government official. The criminal defendant’s right to be charged by a grand jury through either indictment or presentment is available for all offenses that are punishable by imprisonment or carry a fine of $50 or more. -

Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/23/2021 Page No: 1 Trial Docket

CJUS8023 Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/23/2021 Page No: 1 Trial Docket Thursday Trial Date: 9/23/2021 8:30:00 AM Docket #: 1825414 Defendant: ANDERSON , QUINTON LAMAR Charge: DOMESTIC ASSAULT Presiding Judge: STARNES, GARY Division: 5 Court Room: 4 Arresting Officer: SMITH, BRIAN #996, Complaint #: A 132063 2021 Arrest Date: 5/14/2021 Docket #: 1793448 Defendant: APPLEBERRY , BRANDON JAMAL Charge: AGGRAVATED ASSAULT Presiding Judge: WEBB, GERALD Division: 3 Court Room: 3 Arresting Officer: GOULET, JOSEPH #385, Complaint #: A 62533 2021 Arrest Date: 5/26/2021 Docket #: 1852403 Defendant: ATCHLEY , GEORGE FRANKLIN Charge: CRIMINAL TRESPASSING Presiding Judge: STARNES, GARY Division: 5 Court Room: 4 Arresting Officer: SIMON, LUKE #971, Complaint #: A 100031 2021 Arrest Date: 9/17/2021 Docket #: 1814264 Defendant: AVERY , ROBERT CAMERON Charge: THEFT OF PROPERTY Presiding Judge: WEBB, GERALD Division: 3 Court Room: 3 Arresting Officer: SERRET, ANDREW #845, Complaint #: A 091474 2020 Arrest Date: 9/9/2020 Docket #: 1820785 Defendant: BALDWIN , AUNDREA RENEE Charge: CRIMINAL TRESPASSING Presiding Judge: SELL, CHRISTINE MAHN Division: 1 Court Room: 1 Arresting Officer: FRANTOM, MATTHEW #641, Complaint #: M 115725 2020 Arrest Date: 11/14/2020 Docket #: 1815168 Defendant: BARBER , JUSTIN ASHLEY Charge: OBSTRUCTING HIGHWAY OR OTHER PASSAGEWAY Presiding Judge: STARNES, GARY Division: 5 Court Room: 4 Arresting Officer: LONG, SKYLER #659, Complaint #: A 094778 2020 Arrest Date: 9/18/2020 Docket #: 1812424 Defendant: BARNES -

United States District Court Eastern District of Tennessee at Knoxville

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE AT KNOXVILLE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) ) v. ) No. 3:16-CR-94 ) Judge Phillips RASHAN JORDAN ) MEMORANDUM AND ORDER Defendant Rashan Jordan pled guilty to failing to register as a sex offender under the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (“SORNA”), in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2250(a). The United States Probation Office has prepared and disclosed a Presentence Investigation Report (“PSR”) [Doc. 18]. The defendant has filed objections to three of the proposed special conditions of supervised release in paragraphs 93, 100, and 101 of the PSR [Doc. 21]. The Probation Office has responded to the objections and declined to remove the proposed special conditions [Doc. 23]. The government has responded by simply concurring in the Probation Office’s analysis and further noting that the special conditions in question are not mandatory, but rather are conditioned on the discretion of the supervising Probation Officer [Doc. 24]. By way of background, defendant was convicted in the Knox County Criminal Court for attempted aggravated sexual battery for a 1998 offense at the age of 17 and he was thereafter required to register as a sex offender. The defendant has a lengthy criminal history and a history of probation revocations since that time, but he has had no further Case 3:16-cr-00094-TWP-HBG Document 25 Filed 02/15/17 Page 1 of 7 PageID #: <pageID> convictions or arrests for a sex offense. In the instant case, the Knox County General Sessions Court issued warrants for the defendant in September 2015 for sex offender registry violations and community supervision violations. -

Fair Trial Vis-À-Vis Criminal Justice Administration: a Critical Study of Indian Criminal Justice System

Journal of Law and Conflict Resolution Vol. 2(4), pp. 66-73, April 2010 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JLCR ISSN 2006 - 9804 © 2010 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Fair trial vis-à-vis criminal justice administration: A critical study of Indian criminal justice system Neeraj Tiwari Indian Law Institute, New Delhi, India. E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted 1 March, 2010 Every civilised nation must have one thing common in their criminal justice administration system that is minimum fair trial rights to every accused person irrespective of his or her status. It is settled in common law and also adopted by other countries too that criminal prosecution starts with ‘presumption of innocence’ and the guilt must be proved beyond reasonable doubt. This paper proposes to trace different dimensions of fair trial standards under Indian criminal justice system and will also focus on the role of defence counsel in the process of achieving ends of justice, as he is the only person on whom the lonesome accused can repose his trust. Key words: Fair trial, Indian criminal justice system and defence counsel. INTRODUCTION The right to a fair trial is a norm of international human (hereinafter as ICCPR)3 reaffirmed the objects of UDHR rights law and also adopted by many countries in their and provides that procedural law.1 It is designed to protect individuals from the unlawful and arbitrary curtailment or deprivation of “Everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public their basic rights and freedoms, the most prominent of hearing by a competent, independent and which are the right to life and liberty of the person. -

The Administration of Criminal Justice in Malaysia: the Role and Function of Prosecution

107TH INTERNATIONAL TRAINING COURSE PARTICIPANTS’ PAPERS THE ADMINISTRATION OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN MALAYSIA: THE ROLE AND FUNCTION OF PROSECUTION Abdul Razak Bin Haji Mohamad Hassan* INTRODUCTION PART I Malaysia as a political entity came into A. Constitutional History being on 16 September 1963, formed by The territories of Malaysia had been part federating the then independent of the British Empire for a long time. After Federation of Malaya with Singapore, the Second World War, there was a brief North Borneo (renamed Sabah) and period of British military administration. Sarawak, the new federation being A civilian government came into being in Malaysia and remaining and independent 1946 in the form of a federation known as country within the Commonwealth. On 9 the Malayan Union consisting of the eleven August 1965, Singapore separated to states of what is now known as West become a fully independent republic within Malaysia. This Federation of Malaya the Commonwealth. So today Malaysia is attained its independence on 31 August a federation of 13 states, namely Johore, 1957. In 1963, the East Malaysian states Kedah, Kelantan, Selangor, Negeri of Sabah and Sarawak joined the Sembilan, Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Federation and was renamed “Malaysia”. Trengganu, Malacca, Penang, Sabah and Sarawak, plus a compliment of two federal B. Parliamentary Democracy and territories namely, Kuala Lumpur and Constitutional Monarchy Labuan. The Federal constitution provides for a Insofar as its legal system is concerned, parliamentary democracy at both federal it was inherited from the British when the and state levels. The members of each state Royal Charter of Justice was introduced in legislature are wholly elected and each Penang on 25 March 1807 under the aegis state has a hereditary ruler (the Sultan) of the East India Company. -

Expungement Worksheet Telephone: 864-596-2630 Spartanburg SC 29306 (Spartanburg/Cherokee Only) Telefax: 864-596-2268

State of South Carolina Seventh Judicial Circuit Solicitor’s Office Barry J. Barnette, Circuit Solicitor 180 Library Street Expungement Worksheet Telephone: 864-596-2630 Spartanburg SC 29306 (Spartanburg/Cherokee Only) Telefax: 864-596-2268 All fees must be submitted at the time of application (Money Orders Only). Each section below can only be used once in a lifetime except 17-1-40 dismissed charges. Fees are non-refundable regardless of whether the charge is found to be statutorily ineligible for expungement or in the Solicitor or his designee does not consent to the expungement. If you pled guilty, paid a fine or served probation, parole or prison time, you must provide documentation of the conviction date, completion of the sentence and all fines/fees must have been paid. If you are unsure of your criminal history you may check your NCIC record on the following website, https://catch.sled.sc.gov/. Our office will not provide you with a copy of your criminal history. Please check the box indicating why you think that you are eligible for an expungement. 1. Successful Completion of a Diversion Program. Director of the program must verify eligibility. Fees are due at the time of application. Cannot have an expungement under each section more than once in a lifetime. Fees are due at the time of application. Fees: $250.00 PTI + $35.00 Clerk of Court (2 separate money orders) §17-22-150 Pre-Trial Intervention (PTI) §17-22-530 Alcohol Education Program (AEP) §17-22-330 Traffic Education Program (TEP) 2. Dismissed (§17-1-40) Charge(s) was dismissed or was found not guilty. -

Petition to Modify ) Tennessee Supreme Court Rule 13, ) Section 5(A)(1) and (5)(D)(1) ) )

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE AT NASHVILLE In re: ) ) No. ___________________________ Petition to Modify ) Tennessee Supreme Court Rule 13, ) Section 5(a)(1) and (5)(d)(1) ) ) PETITION TO MODIFY TENNESSEE SUPREME COURT RULE 13, SECTION 5 (a)(1) and 5(d)(1) This Court “welcomes the continuing criticisms of its Rules,” which “never become final, and are always subject to change.” Barger v. Brock, 535 S.W.2d 337, 342 (Tenn. 1976). “When any individual deems any Rule of Court to be objectionable from any standpoint, it is his privilege to petition the Court for its elimination or modification.” Id. Petitioners are members of the Tennessee bar who seek to ensure that people accused of crimes in Tennessee’s courts can access the resources necessary to prepare and present their defense and protect their constitutional rights. Tennessee Supreme Court Rule 13, § 5(a)(1) provides indigent criminal defendants with expert, investigative, and other support services at State expense when the court presiding over the case finds such services are necessary to ensure the protection of their constitutional rights. Nevertheless, the Administrative Office of the Courts (“AOC”) Director and the Chief Justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court routinely vacate orders issued by General Sessions judges authorizing services under Rule 13, § 5(a)(1). They do so based on their interpretation that the Rule does not apply in General Sessions courts, but only to cases in the “trial court.” For the same reason, they routinely deny expert and investigative services approved by Criminal Courts for defendants whose cases are bound over, but not yet indicted. -

Rules of Chancery Court Procedure 17 Judicial

RULES OF CHANCERY COURT PROCEDURE 17TH JUDICIAL DISTRICT These rules are to be used for informational purposes only. To obtain an official copy, please contact the Circuit Court Clerk for the 17th District GENERAL RULES Rule 1010. Sessions of Court. Regular sessions of Chancery Court will be held in Bedford County on the third Monday of May and November; in Lincoln County on the second Monday of March and September; in Marshall County on the first Monday of February and August; and in Moore County on the third Monday of March and September. The chancellor will maintain regular days in each county and said regular days shall be posted with the clerk and master in each county. The regular days are subject to change in the event of holidays, judicial conferences and other events that may necessitate deviation from the regular days. The chancellor will notify the clerk and master of the affected county of the changes. Rule 1011. Docket Call. The Court will call the docket at the opening of its regular sessions. The Court may hold docket calls at other times to ascertain the status of cases and set deadlines for their disposition. The Court may dismiss old cases for failure of prosecution where they have been dormant without cause shown for an extended time. The Court will dismiss any case, unless family law related, that has been filed for two years or more unless counsel of record enters a scheduling order setting out deadlines for the completion of all discovery, the argument of pre-trial matters, and the setting of a pre-trial conference and trial date at the first call of the docket subsequent to the two year anniversary date. -

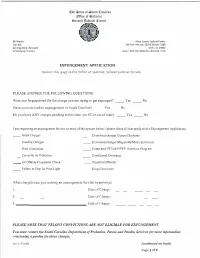

EXPUNGEMENT APPLICATION (Submit This Page to the Office of Solicitor, Second Judicial Circuit)

'Qi:Oe $)tateOf $)0Ut(J QI:arolina (!&ffice of $)Olicitor $)l'COllb3'/nbicial QI:irmit Bill Weeks Aiken County Judicial Center Solicitor 109 Park Avenue, SE/PO Drawer 3368 Serving Aiken, Barnwell, Aiken, SC 29802 & Bamberg Counties phone: 803-502-9000/Fax: 803-642-7530 EXPUNGEMENT APPLICATION (Submit this page to the Office of Solicitor, Second Judicial Circuit) PLEASE ANSWER THE FOLLOWING QUESTIONS: Were you fingerprinted for the charge you are trying to get expunged? __ Yes __ No Have you ever had an expungement in South Carolina? __ Yes __ No Do you have ANY charges pending at this time: (in SC or out of state) __ Yes __ No I am requesting an expungement forone or more of the options below: (please check all that apply to this Expungement Application) __ Adult Charges __ Dismissed charges General Sessions __ Juvenile Charges __ Dismissed charges Magistrate/Municipal Court Prior Conviction __ Completed PTI/AEP/TEP Diversion Program __ Currently on Probation __ Conditional Discharge 1st Offense Fraudulent Check Youthful Offender __ Failure to Stop for Blue Light __ Drug Conviction What charge(s) are you seeking an expungement for (list by priority): I. ___________________ Date of Charge: ____________ 2. __________________ Date of Charge: ____________ 3. Date of Charge: ____________ PLEASE NOTE THAT FELONY CONVICTIONS ARE NOT ELIGIBLE FOR EXPUNGEMENT. You must contact the South Carolina Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services for more information concerning a pardon for those charges. (di 12-17-2019) (continued on back) Page -

SUPREME COURT of INDIA Page 1 of 3 PETITIONER: TARLOK SINGH

http://JUDIS.NIC.IN SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Page 1 of 3 PETITIONER: TARLOK SINGH Vs. RESPONDENT: STATE OF PUNJAB DATE OF JUDGMENT28/04/1977 BENCH: KRISHNAIYER, V.R. BENCH: KRISHNAIYER, V.R. KAILASAM, P.S. CITATION: 1977 AIR 1747 1977 SCR (3) 711 1977 SCC (3) 218 ACT: Criminal Procedure Code (Act 2 of 1974), 1973--Section 235, object and scope of. HEADNOTE: The-appellant was convicted along with two other accused under s. 302 I.P.C. and sentenced to death while the other two were sentenced to life imprisonment. In appeal to this Court against the orders of the High Court confirming the death sentence imposed, the special leave was granted limit- ed to sentence. Allowing the Criminal Appeal No. 337 of 1976 in part and modifying the death sentence to one of life imprisonment, the Court, HELD: (1) The object of s. 235 Cr.P.C 1974 is to give a fresh opportunity to the convicted person to bring to the notice of the court such circumstances as may help the court in awarding an appropriate sentence have regard to the per- sonal, social and other circumstances of the case.[712 D] (2) Failure to give an opportunity under s" 235(2) Cr.P.C. will not affect the conviction under any circum- stance. In a murder case where the charge is made out the limited question is as between the two sentences prescribed under the Penal Code. If the minimum sentence is imposed. question of providing an opportunity under s. 235 would not arise. [712 F] (3) The hearing contemplated by s. -

Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/29/2021 Page No: 1 Master Docket by Agency / Officer

CJUS8043 Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/29/2021 Page No: 1 Master Docket By Agency / Officer Arresting Officer: Docket #: 1848173 Defendant: ROOKS , CHRISTOPHER SHAWN Charge: Failure To Appear Trial Date: 09/29/2021 8:30 AM Wednesday Court Room: 4 Presiding Judge: SELL, CHRISTINE MAHN Division: 1 Disposition: CJUS8043 Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/29/2021 Page No: 2 Master Docket By Agency / Officer Arresting Officer: CUBA, JUAN #348, Docket #: 1806507 Defendant: WALKER , DARRELL DEWAYNE Charge: THEFT OF PROPERTY (CONDUCT INVOLV.MERCHANDISE) (UNDER 1000) Trial Date: 09/29/2021 8:30 AM Wednesday Court Room: 4 Presiding Judge: SELL, CHRISTINE MAHN Division: 1 Disposition: CJUS8043 Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/29/2021 Page No: 3 Master Docket By Agency / Officer Arresting Officer: DAY, RONALD #2741, Docket #: 1852080 Defendant: SMITH , QUDARIUS DEMOND Charge: FAILURE TO APPEAR Trial Date: 09/30/2021 8:30 AM Thursday Court Room: 4 Presiding Judge: SELL, CHRISTINE MAHN Division: 1 Disposition: CJUS8043 Hamilton County General Sessions Court - Criminal Division 9/29/2021 Page No: 4 Master Docket By Agency / Officer Arresting Officer: FLANAGAN, KEVEN #1017, D Docket #: 1832392 Defendant: BROWN , JACQUELINE R Charge: THEFT OF PROPERTY (CONDUCT INVOLV.MERCHANDISE) Trial Date: 09/29/2021 8:30 AM Wednesday Court Room: 1 Presiding Judge: McVEAGH, ALEX Division: 2 Disposition: Docket #: 1809001 Defendant: TIPTON , GLENNA MARCELL Charge: THEFT OF PROPERTY (UNDER