Judicial Discretion in the Modern Sentencing Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book 1 Tuesday, 23 December 2014

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Book 1 Tuesday, 23 December 2014 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable ALEX CHERNOV, AC, QC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC The ministry Premier ......................................................... The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education ............................. The Hon. J. A. Merlino, MP Treasurer ....................................................... The Hon. T. H. Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Employment ............ The Hon. J. Allan, MP Minister for Industry and Minister for Energy and Resources ........... The Hon. L. D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Roads and Road Safety and Minister for Ports ............. The Hon. L. A. Donnellan, MP Minister for Tourism and Major Events, Minister for Sport and Minister for Veterans .................................................. The Hon. J. H. Eren, MP Minister for Housing, Disability and Ageing, Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries ........... The Hon. M. P. Foley, MP Minister for Emergency Services and Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation .................................. The Hon. J. F. Garrett, MP Minister for Health and Minister for Ambulance Services .............. The Hon. J. Hennessy, MP Minister for Training and Skills .................................... The Hon. S. R. Herbert, MLC Minister for Local Government, Minister for Aboriginal Affairs and Minister for Industrial Relations ................................. The Hon. N. M. Hutchins, MP Special Minister of State .......................................... The Hon. G. Jennings, MLC Minister for Families and Children, and Minister for Youth Affairs ...... The Hon. J. Mikakos, MLC Minister for Environment, Climate Change and Water ................. The Hon. L. -

Ministerial Careers and Accountability in the Australian Commonwealth Government / Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis

AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT AND MINISTERIAL CAREERS ACCOUNTABILITYIN THE AUSTRALIAN COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT Edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Ministerial careers and accountability in the Australian Commonwealth government / edited by Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis. ISBN: 9781922144003 (pbk.) 9781922144010 (ebook) Series: ANZSOG series Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Politicians--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Ethical behavior. Political ethics--Australia. Politicians--Australia--Public opinion. Australia--Politics and government. Australia--Politics and government--Public opinion. Other Authors/Contributors: Dowding, Keith M. Lewis, Chris. Dewey Number: 324.220994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2012 ANU E Press Contents 1. Hiring, Firing, Roles and Responsibilities. 1 Keith Dowding and Chris Lewis 2. Ministers as Ministries and the Logic of their Collective Action . 15 John Wanna 3. Predicting Cabinet Ministers: A psychological approach ..... 35 Michael Dalvean 4. Democratic Ambivalence? Ministerial attitudes to party and parliamentary scrutiny ........................... 67 James Walter 5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament ................ 95 Phil Larkin 6. The Pattern of Forced Exits from the Ministry ........... 115 Keith Dowding, Chris Lewis and Adam Packer 7. Ministers and Scandals ......................... -

Parliamentary Questions

About Parliament - Sheet 22 Parliamentary Questions Parliamentary questions are an important means Questions without Notice used by members of Parliament to ensure the (Question Time) government is accountable for its policies and actions to the Parliament and, through the Parliament, to the Questions without Notice are asked orally by people. Opposition or Government backbench members during Question Time in the House. Question Time is In the parliamentary chambers, questions are used a set part of each sitting day, and occurs in both by members on both sides of the house to ask a houses. minister about matters of concern relating to government policy within the minister’s portfolio. In the Legislative Assembly, ministers are asked Questions may also be asked of a member regarding questions for approximately 45 minutes every sitting any matter connected with the business of the house day starting at 2.00 pm or shortly thereafter. for which the member has charge, and also to a In the Legislative Council, Question Time typically member chairing a committee. takes place for approximately 30 minutes starting at 4.30 pm each sitting day. Questions must conform to the rules or the Standing Orders of each house. The Speaker in the Legislative Question Time is one of the liveliest times in a Assembly and the President in the Legislative Council parliamentary sitting day. Generally all members are may disallow or edit a question that is considered to in attendance in the house at this time, when current not conform to the house’s Standing Orders. issues are raised. For this reason, Question Time attracts media attention, with televised extracts Questions asked of a minister must be brief, must not being regularly used in television news programs. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION THURSDAY, 20 JUNE 2019 Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier ........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Education ......................... The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Transport Infrastructure ............................... The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Crime Prevention, Minister for Corrections, Minister for Youth Justice and Minister for Victim Support .................... The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change, and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................. The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ....................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Mental Health, Minister for Equality and Minister for Creative Industries ............................................ The Hon. MP Foley, MP Attorney-General and Minister for Workplace Safety ................. The Hon. J Hennessy, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Ports and Freight -

Does Question Time Fulfil Its Role of Ensuring Accountability?

Does Question Time fulfil its role of ensuring accountability? Parameswary Rasiah University of Western Australia Discussion Paper 14/06 (April 2006) Democratic Audit of Australia Australian National University Canberra, ACT 0200 Australia http://democratic.audit.anu.edu.au My argument is that Question Time (i.e. Questions Without Notice) does not fulfill its role of ensuring the government is held accountable for its actions, based on three premises. Firstly, ministers do evade answering questions, specifically those asked by opposition MPs; secondly, the speaker’s inaction or rulings when evasion occurs and thirdly, ‘Dorothy Dixers’ (friendly questions) are widely used by the government to evade accountability. Evasion The popularly held belief that ministers frequently evade answering questions during Question Time is supported by empirical evidence. My study is based on an analytical framework derived from works by others1 in the field of evasion (or equivocation) in political news interviews. It involved the classification of responses as ‘answers’ (direct or indirect), ‘intermediate responses’ (such as not having the information at hand or pointing out incorrect information in the question), and ‘evasions’ based on specific criteria. The data were Hansard transcripts of the House of Representatives’ Questions Without Notice in February 2003 dealing only with questions and responses on the topic of Iraq. This topic was chosen because it was and still is a relevant topic of discussion today especially in terms of whether the Iraqi regime posed a sufficient enough threat to justify military action by Australia the following month (March 2003) as part of the ‘coalition of the willing’. There were 41 such questions which represented approximately one third of all questions on Iraq for the whole of that year. -

Report: Inquiry Into the Implementation of The

7 CHAPTER 2 APOLOGIES, REDRESS AND JUDICIAL INQUIRIES 2.1 This chapter considers some of the major issues raised in evidence concerning the implementation of the recommendations of the Forgotten Australians and Lost Innocents reports. These are: • the requirement for the Commonwealth to provided national leadership in ensuring coordinated and comprehensive responses to care leaver issues; • national and State apologies to care leavers; • reparation and redress schemes; and • the need for judicial inquiries and/or a Royal Commission. 2.2 In most cases, both the Lost Innocents and Forgotten Australians reports made specific recommendations going to these issues. However, it is also the case that many of the recommendations in Forgotten Australians applies to care leavers more generally, and should be understood as being potentially relevant to any person who experienced out-of-home care in Australia in the last century, regardless of whether they experienced care in a State, religious or charitable institution; or indeed in some other setting, such as foster care.1 The term 'care leavers' as it is used in the following chapter thus may include, as relevant, former child migrants and members of the stolen generation.2 National leadership role required from the Commonwealth Lost Innocents 2.3 The former Commonwealth government issued its response to the Lost Innocents report on 14 May 2002. In the preamble to its response the government welcomed the report as a 'sensitive, comprehensive and insightful appraisal of child migration schemes and child migrants' experiences in Australia'; and acknowledged that the legacy of the child migration schemes must be addressed. -

The Minority Report

THE MINORITY REPORT Inquiry into the Victorian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. INTRODUCTION On 23 April 2020, in the Victorian Parliament during Question Time, the Premier of Victoria, the Hon Daniel Andrews MP, stated confidently: “[The Public Accounts and Estimates Committee] is the pre-eminent committee in our Parliament, and it ought to be given the opportunity to review the performance of the government. I am confident that it will do that without fear or favour.”1 The Andrews Labor Government’s handling of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, in particular the deadly second wave outbreak of infections, has been nothing short of disastrous. It has had dramatic impacts on all Victorians, with the loss of more than 800 lives, hundreds of thousands of jobs, many thousands of businesses and the deprivation of the liberty of millions of Victorians. The Public Accounts and Estimates Committee (PAEC) was given the task of reviewing the Government’s handling of the biggest health, social and economic crisis in generations. In the view of the minority members of the Committee, this was the wrong choice. A committee dominated by Labor Government members and chaired by a Labor Government member, with both a deliberative and a casting vote on all matters, would never deliver the necessary critical examination or accountability necessary in this crisis. Evidence gathered in preparation for this Inquiry showed that Victoria was the only jurisdiction in Australia with a Parliamentary committee reviewing a government response to the pandemic, with a government majority. When fundamental mistakes made by government caused a second wave of COVID-19 that cost 800 Victorian lives, deepened and extended Victoria’s social and economic misery and led to enormous imposts of the liberty of Victorians, a committee dominated by a Labor Government majority was entirely inappropriate. -

Operation of the 1994 Qld Estimates Committees: a Retrospective

AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP (Queensland Chapter) Operation of the 1994 Qld Estimates Committees: A Retrospective Dr PAUL REYNOLDS Hon WARWICK PARER, Senator Mr ROSS DUNNING (Former Senior Public Servant, Qld Government, and CEO Evans Deakins Industries) 21 NOV 1994 Parliament House Brisbane Reported by Parliamentary Reporting Staff Dr Reynolds: Thank you ladies and gentlemen for your attendance. The Honourable David Hamill is ill and cannot join us. However, he insisted that some of his points should be given to the meeting. I will do that on his behalf. I can begin by observing that Estimates matters have always been vital to the operation of Parliament. The right to tax was central to the crisis in the Constitution in the seventeenth century. The battle between Crown and Parliament which culminated in the Cromwellian Interregnum of 1649 to 1658 was fundamentally about the right to tax and who possessed that right. It was then resolved on the battlefield. The Parliament had the right to tax but upon this the constitutional seal was set in 1688 when, in the Glorious Revolution, William and Mary, as joint monarchs, accepted without let or hindrance Parliament's unchallenged right to tax. It took another 150 years of British parliamentary evolution for this principle to be worked through in all its particulars but, if we take an historical dimension, we can see that the right to tax is the right to govern and the right to govern confers the stamp of legitimacy on Government. It is pertinent for our Constitution that, only once since Federation, namely in 1975, has this principle been called into question. -

Can the Opposition Effectively Ensure Government Accountability in Question Time? an Empirical Study

Can the Opposition Effectively Ensure Government Accountability in Question Time? An empirical study Parameswary Rasiah* Since Parliament is at the centre of our political system, the Executive (consisting of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Ministers) is accountable to it. Government accountability is achieved through several parliamentary mechanisms including questioning, debates and parliamentary committees of inquiry. Two kinds of questions are permitted to be asked of Ministers; i.e. questions without notice and questions on notice. Questions without notice, asked during Question Time, are oral questions to Ministers who are expected to respond immediately. Questions on notice, on the other hand, are written questions lodged by members of parliament (MPs), which appear in the Notice Paper, to which Ministers respond also in writing. Question Time is the more popular of the two forums and it is well attended by parliamentarians (Sinclair 1982) since it ‘attracts a consistently high degree of media attention’ (Kelly and Harris 2001, p. 2). The practice of asking questions without notice evolved in a rather ‘ad hoc manner’ (Barlin 1997, House of Representatives infosheet 2002). For a long while, the practice of asking questions without notice had no official status and was greatly influenced by practice and convention. It was finally included in the routine business of the House when the House of Representatives formally adopted standing orders permitting such questions in 1950 (Barlin 1997, House of Representatives infosheet 2002). Question Time and Accountability In any society it is fundamental that there be a system of accountability that ‘is supposed to ensure that any government acts in a way broadly approved by the community’ (Hughes, 1998, p. -

5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament

5. Ministerial Accountability to Parliament Phil Larkin Introduction: The decline of parliament? For many commentators, parliament’s role in holding governments to account is the subject of laments for a better past and a central element in claims of a decline of parliament and of a democratic deficit (for a recent review, see the discussion in Flinders and Kelso 2011). The claim that parliament’s role has been undermined has a number of dimensions. The primary one centres on the rise of organised and disciplined parties. In the parliamentary ‘golden age’ of the nineteenth century, with little in the way of disciplined parties, the executive could only maintain parliament’s confidence by being constantly accountable to the legislature’s wishes. With the emergence of organised parties, however, the executive effectively gained control over the legislature: the party leadership was able to use its control of promotion from the backbenches to ministerial positions or to committee chairs to enforce discipline on its members and, commanding a majority of members of the lower chamber, parliamentary government became a byword for executive dominance of the legislature, with parliamentarians reduced to ‘lobby fodder’ and executive accountability achieved only through the ballot box at election time. Flinders and Kelso (2011) note that by the early decades of the twentieth century the decline narrative had become dominant. It still—an academic backlash notwithstanding—holds considerable sway in the popular imagination: the Power report was an exemplar of the tradition, concluding that ‘the Executive in Britain is now more powerful in relation to parliament than it has been probably since the time of Walpole’ (Power Inquiry 2006, 128). -

Interim Report Sitting Hours and Operation of the House

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA Legislative Assembly Standing Orders Committee Inquiry into sitting hours and operation of the House Interim Report December 2015 Standing Orders Committee Report No. 1 58th Parliament PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA Legislative Assembly Standing Orders Committee Inquiry into sitting hours and operation of the House Interim Report Parliament of Victoria Legislative Assembly Standing Orders Committee Ordered to be published VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER December 2015 PP No 121, Session 2014-15 ISBN 978 1 925458 10 7 (print version) 978 1 925458 11 4 (PDF version) Committee membership Hon Telmo Languiller MP Hon Jacinta Allan MP Hon Louise Asher MP Speaker of the Legislative Leader of the House Brighton Assembly (Chair) Bendigo East Tarneit Mr Colin Brooks MP Hon Robert Clark MP Mr Sam Hibbins MP Bundoora Manager of Opposition Prahran Business Box Hill Hon David Hodgett MP Ms Marlene Kairouz MP Mr Don Nardella MP Deputy Leader of Kororoit Deputy Speaker the Liberal Party Melton Croydon Ms Steph Ryan MP Ms Suzanna Sheed MP Deputy Leader of Shepparton the Nationals Euroa ii Legislative Assembly Standing Orders Committee Committee secretariat Staff Mr Ray Purdey, Clerk of the Legislative Assembly Ms Bridget Noonan, Deputy Clerk of the Legislative Assembly Mr Robert McDonald, Assistant Clerk Procedure and Serjeant-at-Arms (Secretary) Committee contact details Address Legislative Assembly Standing Orders Committee Department of the Legislative Assembly Parliament House, Spring Street EAST MELBOURNE VIC 30022 Phone 61 3 9651 8553 Web www.parliament.vic.gov.au/la-standing-orders This report is also available online at the Committee’s website. Inquiry into sitting hours and operation of the House – Interim Report iii Report 1. -

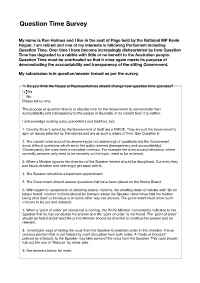

Question Time Survey

Question Time Survey My name is Ron Holmes and I live in the seat of Page held by the National MP Kevin Hogan. I am retired and one of my interests is following Parliament including Question Time. Over time I have become increasingly disheartened by how Question Time has degraded to a rabble with little or no benefit to the Australian people. Question Time must be overhauled so that it once again meets its purpose of demonstrating the accountability and transparency of the sitting Government. My submission is in question/answer format as per the survey. 1. Do you think the House of Representatives should change how question time operates? Yes No Please tell us why. The purpose of question time is to allocate time for the Government to demonstrate their accountability and transparency to the people of Australia. In its current form it is neither. I acknowledge existing rules, precedents and tradition, but: 1. Dorothy Dixer's asked by the Government of itself are a FARCE. They are just the Government's spin on issues selected by themselves and are as such a waste of time. See Question 6. 2. The current rules around the answering (or not answering) of questions lets the Government avoid difficult questions which are in the public interest (transparency and accountability). Consequently the rules need a complete overhaul. For example the rules around relevance, where currently answers only need to be remotely on the topic, need to be reviewed. 3. When a Minister ignores the direction of the Speaker he/she should be disciplined.