WHALLEY V. LANCASHIRE, &C., RAILWAY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11Th International Conference International Society for Equitation Science August 5-8, 2015 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

11th International Conference International Society for Equitation Science August 5-8, 2015 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada International Society for Equitation Science Presents 11th International Equitation Science Conference August 5-8, 2015 University of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned. Nothing from this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a computerized system or published in any form or in any manner, including electronic, mechanical, reprographic or photographic, without prior written permission from the publisher. The individual contributions in this publication and any liabilities arising from them remain the responsibility of the authors. Views expressed in all contributions are those of the authors and not those of the ISES or publisher. ISBN: 978-1-943842-25-4 First published, 2015 Copying permitted with proper citing of source Editors: Camie Heleski, Katrina Merkies COVER PHOTO CREDIT: ANDREA BLAIR, PAPER HORSE PHOTOGRAPHY These proceedings will be available electronically within 90 days of the conference at http://www.equitationscience.com/proceedings 1 Table of contents Scientific committee members……………………………………………………..3 Welcome by the local organizers…………………………………………………..4 Welcome by the ISES president……………………………………………………..5 Programme…………………………………………………………………….………………6 Poster Abstract Numbers………………………………………………………………12 Abstracts – Plenary Talks……………………………………………………………….15 -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Attractive Method of Vaccine

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jon D. Piganellifor the degree ofDoctor of Philosophyin Microbiology presented on June 6. 1994 Title:Development of Enteric Protected Vaccines for Aauaculture. Abstract approved: Stephen L. Kaattari At present all vaccines for fish are primarily delivered either by injection or immersion which introduces added stress and labor. A more attractive method of vaccine delivery is oral administration using an enteric protection system, Enteric Coated Antigen Microspheres (ECAMs), which can be utilized for a variety of antigenic forms. Relative efficacy of ECAMs was compared by inducing an antibody response in fish via injection (ip), immersion (im) or by ECAMs. Results showed that ECAMs were as effective as ip and im in inducing an antibody response to lipopolysaccharde and protein antigens. ECAMs were able to protect the protein antigen from gastric degradation. The ECAMs were employed to deliver a prototype vaccine for Renibacterium salmoninarum(Rs), the etiological agent of bacterial kidney disease. Upon characterization of the Rs antigens, one predominant cell- associated and extracellular protein (ECP), p57 was identified. The p57 molecule is elaborated in high concentrations in infected fish and exhibits pathogenic activitiesin vitro whichappear to suppress the immune response. Our studies have revealed that a 370C incubation of R. salmoninarum cells decreased the amount of p57 by the inductionof an autoproteolytic activity. This activity was exploited to producea prototype vaccine that was delivered by intraperitoneal injection (ip)and demonstrated a significant increase inmean time of death upon challenge by injection. A second experimentwas conducted using a natural exposure (bath challenge) and the heat treated, p57 -Rs cellswere delivered using ECAMs and ip administration. -

2019 Bryan Clay Invitational

Finished Results - Contractor License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 9:44 AM 4/20/2019 Page 1 2019 Bryan Clay Invitational - 4/17/2019 to 4/19/2019 Hosted by: Azusa Pacific University Cougar Stadium Results Event 1 Men 10000 Meter Run Heat 2 ================================================================ APU Stadium: # 29:55.26 1994 David Kogo, Lubbock Christ Name Year School Finals ================================================================ Finals 1 Jones, Blake FR Illinois-Spr 30:28.49 2 Ortiz, Daniel SR Bengalas MX 30:32.96 3 Ward, Hugo SO Pomona-Pitzer 30:49.52 4 Hill, Daniel SR Pomona-Pitzer 31:05.53 5 Dillon, Taylor SO Weber State 31:11.00 6 Stone, Jacob FR Weber State 31:13.34 7 Werth, Layton SR Fort Hays St. 31:24.14 8 Biehl, Joseph SO Grand Canyon 31:29.95 9 Drabot, Joseph SR Bellarmine 31:45.42 10 Orar, Aaron FR Central Arizona 31:46.87 11 Romero, Julian JR UC San Diego 31:48.32 12 Bautista, Sebastian FR UC Irvine 31:50.99 13 Escobar, Angel JR Biola 31:52.06 14 Vickstrom, Ian FR Portland State 32:02.14 15 Marin, Robert JR Unattached 32:04.90 16 Contreras, Jose SR Francisco Pacheco 32:15.11 17 Donnel, Jared FR Biola 32:18.69 18 Riggsby, Alex SO St. Mary's (Cal.) 32:21.71 19 Blake, Samuel JR UC San Diego 32:23.07 20 Hiserote, Tyler JR Illinois-Spr 32:26.27 21 Stark, Ryan SO Illinois-Spr 33:07.81 22 Milla, Marcos FR UC San Diego 33:10.27 23 Troe, Caleb SR Concordia-St. -

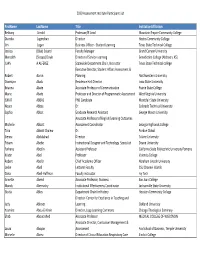

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List Firstname Lastname Title

2020 Assessment Institute Participant List FirstName LastName Title InstitutionAffiliation Bethany Arnold Professor/IE Lead Mountain Empire Community College Diandra Jugmohan Director Hostos Community College Jim Logan Business Officer ‐ Student Learning Texas State Technical College Jessica (Blair) Soland Faculty Manager Grand Canyon University Meredith (Stoops) Doyle Director of Service‐Learning Benedictine College (Atchison, KS) JUAN A ALFEREZ Statewide Department Chair, Instructor Texas State Technical college Executive Director, Student Affairs Assessment & Robert Aaron Planning Northwestern University Osomiyor Abalu Residence Hall Director Iowa State University Brianna Abate Associate Professor of Communication Prairie State College Marie Abate Professor and Director of Programmatic Assessment West Virginia University ISMAT ABBAS PhD Candidate Montclair State University Noura Abbas Dr. Colorado Technical University Sophia Abbot Graduate Research Assistant George Mason University Associate Professor of English/Learning Outcomes Michelle Abbott Assessment Coordinator Georgia Highlands College Talia Abbott Chalew Dr. Purdue Global Sienna Abdulahad Director Tulane University Fitsum Abebe Instructional Designer and Technology Specialist Doane University Farhana Abedin Assistant Professor California State Polytechnic University Pomona Kristin Abel Professor Valencia College Robert Abel Jr Chief Academic Officer Abraham Lincoln University Leslie Abell Lecturer Faculty CSU Channel Islands Dana Abell‐Huffman Faculty instructor Ivy Tech Annette -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected -

Equine Section Results - 2017

Equine Section Results - 2017 SECTION: RIDDEN HUNTERS CLASS: H0001/0001 FOUR YEAR OLD HUNTER, GELDING OR MARE FOALED IN 2013. HORSES ENTERED IN THIS CLASS MAY ALSO BE ENTERED Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mr M Ainsworth, Ledbury, Herefordshire (1) Boston IV SECTION: RIDDEN HUNTERS CLASS: H0001/0002 GELDING OR MARE, EXCEEDING 14.2 H.H. THAT HAS BEEN REGULARLY HUNTED (IN EXCESS OF 10 TIMES) WITH A RECOG Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Miss E Gibson, Bristol, (13) State Of Play II 2 Mrs F Benger, Axminster, Devon (7) All Torque 3 Mrs R Broad, Liskeard, Cornwall (9) Cool Diamond 4 Miss D Appleby, South Molton, Devon (4) Cracker 5 Mrs H Duckworth & Miss F Jones, Newquay, Cornwall (11) Solomon 6 Mr P J Lobb, Bodmin, Cornwall (17) Derby Park 7 Miss E Vincent, Newquay, Cornwall (25) High Cove SECTION: RIDDEN HUNTERS CLASS: H0001/0003 GELDING OR MARE, 4 YEARS OLD AND OVER, OWNED BY EXHIBITOR, RESIDENT IN CORNWALL. Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mr I Lewis, Redruth, Cornwall (32) Mr Wooster 2 Mrs K Stenning, Callington, Cornwall (34) Wisbeach River Deep 3 Mrs C Fox, Truro, Cornwall (30) Irish Gift 4 Miss C Tinson, Newquay, Cornwall (35) Assagart Master 5 Miss D McLeod, Penryn, Cornwall (33) Ryans Diamond ROYAL CORNWALL SHOW 2017 - EQUINE SECTION RESULTS 22 June 2017 Page 1 of 101 SECTION: RIDDEN HUNTERS CLASS: H0001/0004 SMALL SHOW HUNTER, GELDING OR MARE 4 YEARS OLD AND OVER, EXCEEDING 148CM (14.2 H.H. APPROX) BUT NOT EX Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. -

History of Columbia and Columbia Precinct, Monroe County, Illinois

* * * * HISTORY of COLUMBIA, ILLINOIS COLUMBIA'S * CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION JULY 3, 4 and 5, 1959 HISTORY OF COLUMBIA AND COLUMBIA PRECINCT MONROE COUNTY, ILLINOIS 1859 - 1959 AND CENTENNIAL CELEBRATION COLUMBIA, ILLINOIS JULY 3-4-5, 1959 FOREWORD This year, 1959, marks the 100th anniversary of the in- corporation of Columbia, Illinois, as a town. Because of this, we, on July 3, 4 and 5, 1959, formally celebrate this event by a Centennial celebration. As a part of this celebration, a committee was appointed to write the history of Columbia. The story of Columbia goes back far more than a hun- dred years, and the story would not be complete without the telling of our rich background of early history. For it is a story of hardy pioneering, with sacrifices and heroism. It is a story, too, of simple virtues, lofty ideals and wholesome domestic life. Yet it is a story of civic and military achievements and trail blazing. Underneath it all education and the is deep religious faith and the quest for ; establishment of businesses and commercial enterprises that make for better living. In our Centennial year, we pause to reflect upon our heritage and to survey our future prospects. By this Centennial celebration the people of Columbia wish to publicly express their appreciation for 100 years of blessings and success, and our deep gratitude to our for- bears, even down to those in the dim and distant past whose bravery and fortitude made possible the Columbia of today. To them, and to all the citizens of Columbia is this his- tory dedicated. -

Hunting Lays and Hunting Ways

L LIBKAKY UNIVERSITY^ V PENN5YL\^^NIA. FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP JOHN P. GRIER EX JLIJBKIS HUNTING LAYS AND HUNTING WAYS EX XilBKIS Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/huntinglayshuntiOObirk LORD LISMORE I.enl by Mt-ssrs. K, Ackt, Frotn a painting by J . K. Fernciey /Sw; ; HUNTING LAYS AND HUNTING WAYS AN ANTHOLOGY OF THE CHASE COLLECTED AND RECOLLECTED BY LADY BIRKETT With Fourteen Illustrations from Old Pictures and Prints " My Horse-sounding Horn Invites thee to the Chase—the Sport of Kings Image of War, without its Guilt." SOMERVILLE. PHILADELPHIA MACRAE SMITH COMPANY PUBLISHERS NtW BOLTON CENTER Made and Printed in Great Britain. Richard Clay & Sons, Ltd., Printers, Bungay. ; I N DEDICATED •J " "With the luck of each fence where it's low" (Whyte-Melville) > TO "Whom naught comes amiss, f One horse or another, that country or this Who through falls and bad starts undauntedly still " — will.' Rides up to the motto ' Be with them I (OW Cheshire Hunting Song.) 1l r^ — NOTE I herewith thank the undermentioned for their kind permission to reprint in this volume the following poems, extracts and pictures The Honble. John Fortescue, an extract from Stag Hunting on Exmoor. Sir Henry Newbolt, " A Song of Exmoor," from Poems New and Old. Sir Francis C. Gould, " Exmoor." Messrs. Macmillan & Co., Ltd., for "The Old Squire," by Mr. W. S. Blunt. Messrs. Constable & Co., Ltd., for " Young Reynard," by George Meredith, and " The First Whip " and " The Crutch," by Will. -

Annual GET-TOGETHER 2010 the 2010 AGM Was Held in the Splendid Surroundings of Hungerford Town Hall on the 10Th April

Newsletter Sum2010 8June2010_Layout 2 09/06/2010 18:24 Page 1 WNielwds STumromuetr 2T01r0ust The Wild Trout Trust is dedicated to the conservation of wild trout in Britain and Ireland through protection and restoration of habitat ANNUAL Wild Trout Trust Annual GET-TOGETHER 2010 The 2010 AGM was held in the splendid surroundings of Hungerford Town Hall on the 10th April. Raffle 2010 Edward Twiddy, Chairman of the WTT Trustees, welcomed the assembled company of about seventy five members and introduced two local dignitaries: We have some Barbara Barr, the Constable of the Town and Manor of Hungerford and Robert fantastic prizes this James, Trustee of the Town and Manor of Hungerford. These ancient titles derive from the time when John of Gaunt held lands and other properties in the year – a day’s fishing area and he (and the king) granted them to the townspeople. John of Gaunt was - dinner - B&B, a a man of many achievements but the one of most interest to our members was that he granted the townsfolk the right to fish on the River Kennet; John’s Sage rod, an Orvis descendants challenged this right but lost their court-case when Queen Elizabeth intervened. rod, WTT Life Shaun Leonard, Paul Gaskell, Tim Jacklin and Andy Thomas then Membership and 6 summarised their activities and plans. You will find reports from each of them in the following pages. bottles of malt Dylan Roberts of the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust gave a most interesting address about research into the question “Does more fencing mean whisky. -

Provisional Results (Subject to Final Verification) 03/06/2017 18:05 2017

2017 HUNTER BREEDING H1 HUNTER FILLY, COLT OR GELDING Yearling, foaled in 2016. 1st 4 Mrs Daphne Thorneycroft TIGBOURNE 2nd 5 Maria Williams THE DIADEM OF MOURNE H2 HUNTER FILLY, COLT OR GELDING Two year old, foaled in 2015. 1st 16 Tony Wareham CHARLIE'S GIRL III 2nd 10 Mrs R Dickens LIBRIS ROYAL LADY 3rd 17 Mr M Wood RUDOLPH THE RED NOSE 4th 15 R Stevenson INSPECTOR MONTABLANO 5th 7 Tracey Bonner ASTRAEA H3 HUNTER FILLY, COLT OR GELDING Three years old, foal in 2014. 1st 23 Mrs V Kemp CHALLACOMBE 2nd 22 Mrs Jazmin Hosgood TALLY HO FORRARD 3rd 20 Georgia Coppes KINGS HARLEQUIN II 4th 19 Mrs K De Boorder DREAMCATCHER'S ROCKIN' H4 SMALL HUNTER BROOD MARE Exceeding 148cms but not exceeding 158cms, with foal at foot or a relevant certificate of pregnancy which may be inspected at the show. 1st 31 Sally Hobbs COMBERTON COPELIA 2nd 29 Mr Charles Upham And Mr S Davey TRENAVEY CONSENT H5 HUNTER FOAL Produce of mare shown in class H4. 1st 34 Sally Hobbs COMBETON COPELIA FOAL H6 HUNTER BROOD MARE Exceeding 158cms, with foal at foot or a relevant certificate of pregnancy which may be inspected at the show. 1st 35 Mr Charles Upham And Mr S Davey TRENAVEY IRISH MIST H7 HUNTER FOAL Produce of mare shown in class H6. 1st 39 Mrs A G Loriston - Clarke CATHERSTON TIARA CHAMPIONS & SPECIALS HC2 For the Champion Hunter Breeding From classes H1 to H7 Champion 16 Tony Wareham CHARLIE'S GIRL III Reserve 31 Sally Hobbs COMBERTON COPELIA HC3 For the Champion Hunter Breeding Youngstock In classes H1, H2, H3, H5 and H7. -

2016 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 11/02/16 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (North America) since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (North America) the main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee. Updates made on the IFHA website the horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 11/02/2016 In January 2016, the list of Protected Names contains