The Adriatic Within the Mediterranean: Some Characteristic Shipwrecks from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 05:48:17AM Via Free Access 18 PROCEEDINGS 2ND INTERNATIONAL BAT RESEARCH CONFERENCE

The distribution of bats on the Adriatic islands by Beatrica Dulić & Nikola Tvrtković Zoological Institute, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Institute of Biology of the University, Zagreb, Yugoslavia The bat fauna of the Adriatic islands is very poor- I. Bibliographical data included, 16 species of bats ly known in comparison with that of the coastal from the Adriatic islands (north, middle, and continental regions (Kolombatović, 1882, 1884; south) are known now. Dulić, 1959). Although ten species of bats are REMARKS ON DIFFERENT SPECIES recorded, the data for most of the islands except the island of Lastovo (Dulić, 1968) are scarce, and Rhinolophus ferrumequinum ferrumequinum of an early date. (Schreber, 1774) During the years 1966—1970, mostly in the The Greater Horseshoe Bat is widely distributed summer (July, August), we investigated the bat on the islands. Colonies of about 80 to 150 ani- Adriatic the mals inhabit the islands fauna of some islands, particularly of of Hvar, Vis, and Lastovo. southern 17 each of 5 10 live in the those ones. During trips, to They caves near sea, even par- flooded with days, to 8 islands, 200 bats were collected and tially sea-water (Hvar), but only dur- several hundreds were examined (caught in mist ing the summer. Most are nursing colonies, though nets or taken in caves). The investigated area is in some of them (Lastovo) we found also males. Some isolated shown in fig. 1, the distributionof the bats in table males we found on the same island in an abandoned church, and on the island of Mljet in crevices in stones above the sea. -

Route Planner Central Dalmatia Bases: Sibenik (Biograd/MURTER Jezera/Pirovac) Route 3 (1 Week)

Route planner Central Dalmatia bases: Sibenik (Biograd/MURTER Jezera/Pirovac) route 3 (1 week) DUGI OTOK Sali Biograd NP Telascica VRGADA Pirovac Piskera Murter Skradin KORNAT Vodice ZLARIN Sibenik KAKAN KAPRIJE ZIRJE Primosten day: destination from: to: 1 Saturday Biograd/ Vodice (possible bathing stops: Zlarin or MURTER Jezera/ TIJAT Tijascica) Pirovac/Sibenik 2 Sunday Vodice Skradin 3 Monday Skradin ZLARIN Zlarin or TIJAT Tijascica 4 Tuesday ZLARIN Zlarin or TIJAT KAPRIJE Kaprije or KAKAN Tijascica 5 Wednesday KAPRIJE/KAKAN ZIRJE Vela Stupica 6 Thursday ZIRJE Vela Stupica MURTER Vucigrade, Murter or VRGADA 7 Friday MURTER Vucigrade, Mur- Biograd/MURTER Jezera/Pirovac/Sibenik ter or VRGADA Page 1 Location descriptions Biograd Biograd the „white city“ or royal city is a modern city. For a long time, it has been the residence of medieval Croatian dynasties, whose splendor is still visible in the old town. During the day, life mainly takes place on the beaches and the harbor prome- nade, in the evening the bustle shifts to the promenade of the old town. Numerous shops, restaurants, cafes, bars and ice cream parlors await the tourists. Biograd is a popular port of departure in the heart of Dalmatia. The Pasman Canal and the islands of Pasman and Uglijan, as well as the beautiful world of the Kornati Islands are right on the doorstep. MURTER Jezera, Murter and the bays Murter is also called the gateway to the Kornati, but the peninsula itself has also a lot to offer. The starting port Jezera is a lovely little place with a nice beach, shops, restaurants and bars. -

Route Planner Central Dalmatia Bases: Biograd/MURTER Jezera/Pirovac/Sibenik Route 1 (1 Week)

Route planner Central Dalmatia Bases: Biograd/MURTER Jezera/Pirovac/Sibenik route 1 (1 week) DUGI OTOK Sali Biograd NP Telascica VRGADA Pirovac Vrulje Murter Skradin KORNAT Vodice ZIRJE day: destination from: to: 1 Saturday Biograd/Murter/Pirovac VRGADA or MURTER Murter, Vucigrade, Kosirinia 2 Sunday VRGADA Vodice MURTER 3 Monday Vodice Skradin 4 Tuesday Skradin ŽIRJE Vela Stupica 5 Wednesday ŽIRJE KORNAT / Vrulje Vela Stupica 6 Thursday KORNAT Vrulje Nationalpark Telašcica Bucht oder Sali Über div. Badebuchten auf Pasman retour nach 7 Friday Nationalpark Telašcica Biograd, Murter oder Pirovac page1 Location descriptions Biograd Biograd the „white city“ or royal city is a modern city. For a long time, it has been the residence of medieval Croatian dynasties, whose splendor is still visible in the old town. During the day, life mainly takes place on the beaches and the harbor prome- nade, in the evening the bustle shifts to the promenade of the old town. Numerous shops, restaurants, cafes, bars and ice cream parlors await the tourists. Biograd is a popular port of departure in the heart of Dalmatia. The Pasman Canal and the islands of Pasman and Uglijan, as well as the beautiful world of the Kornati Islands are right on the doorstep. MURTER Jezera, Murter and the bays Murter is also called the gateway to the Kornati, but the peninsula itself has also a lot to offer. The starting port Jezera is a lovely little place with a nice beach, shops, restaurants and bars. The main town of Murter, is a lot bigger and busier. Especially the nightlife of Murter has a lot to offer. -

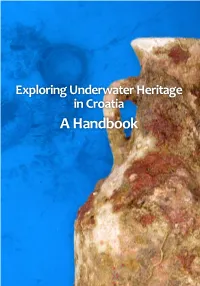

Exploring Underwater Heritage in Croatia a Handbook Exploring Underwater Heritage in Croatia a Handbook

exploring underwater heritage in croatia a handbook exploring underwater heritage in croatia a handbook Zadar, 2009. AN ROMAN PERIOD SHIPWRECK WITH A CARGO OF AMPHORAE ROMaN PeRIOD ShIPWRecK IN The ČaVLIN ShaLLOWS There are several hundred Roman pe- riod shipwrecks in the Croatian part of the Adriatic Sea, the majority of which are devastated, but about a dozen of which have survived the ravages of time and unethical looters. They have been preserved intact, or with only minor damage, which offers underwater archaeologists an oppor- tunity for complete research. The very large number of Roman ship- wrecks is not unexpected, but speaks rather of the intensity of trade and importance of navigation on the eastern side of the Adriatic Sea, and of the dangers our sea hides. Roman period shipwrecks can be dated either by the type of cargo they carried or by some further analysis (the age of the wood, for example), and the datings range from the 4th century BC to the 6th century. The cargos of these ships were varied: from fine pot- tery, vessels and plates, stone construction elements and brick to the most frequent cargo – amphorae. The amphora was used as packag- ing from the period of the Greece colonisation to the late Roman and the Byzantine supremacy. There are remains of shipwrecks with cargos of amphorae that can be researched on the seabed, covered by Archaeological underwater excavation with the aid of a water dredge protective iron cages, and there are those that, as per documentation, need to be raised to the surface and presented on land. -

Split & Central Dalmatia

© Lonely Planet Publications 216 Split & Central Dalmatia Central Dalmatia is the most action-packed, sight-rich and diverse part of Croatia, with dozens of castles, fascinating islands, spectacular beaches, dramatic mountains, quiet ports and an emerg- ing culinary scene, not to mention Split’s Diocletian Palace and medieval Trogir (both Unesco World Heritage sites). In short, this part of Croatia will grip even the most picky visitor. The region stretches from Trogir in the northwest to Ploče in the southeast. Split is its largest city and a hub for bus and boat connections along the Adriatic coast. The rugged DALMATIA DALMATIA 1500m-high Dinaric Range provides the dramatic background to the region. SPLIT & CENTRAL SPLIT & CENTRAL Diocletian’s Palace is a sight like no other (a Roman ruin and the living soul of Split) and it would be a cardinal Dalmatian sin to miss out on the sights, bars, restaurants and general buzz inside it. The Roman ruins in Solin are altogether a more quiet, pensive affair, while Trogir is a tranquil city that’s preserved its fantastic medieval sculpture and architecture. Then there is Hvar Town, the region’s most popular destination, richly ornamented with Renais- sance architecture, good food, a fun atmosphere and tourists – who are in turn ornamented with deep tans, big jewels and shiny yachts. Let’s not forget the coastline: you can choose from the slender and seductive Zlatni Rat on Brač, wonderful beaches in Brela on the Makarska Riviera, secluded coves on Brač, Šolta and Vis, or gorgeous (and nudie) beaches on the Pakleni Islands off Hvar. -

The First Illyrian War: a Study in Roman Imperialism

The First Illyrian War: A Study in Roman Imperialism Catherine A. McPherson Department of History and Classical Studies McGill University, Montreal February, 2012 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts ©Catherine A. McPherson, 2012. Table of Contents Abstract ……………………………………………….……………............2 Abrégé……………………………………...………….……………………3 Acknowledgements………………………………….……………………...4 Introduction…………………………………………………………………5 Chapter One Sources and Approaches………………………………….………………...9 Chapter Two Illyria and the Illyrians ……………………………………………………25 Chapter Three North-Western Greece in the Later Third Century………………………..41 Chapter Four Rome and the Outbreak of War…………………………………..……….51 Chapter Five The Conclusion of the First Illyrian War……………….…………………77 Conclusion …………………………………………………...…….……102 Bibliography……………………………………………………………..104 2 Abstract This paper presents a detailed case study in early Roman imperialism in the Greek East: the First Illyrian War (229/8 B.C.), Rome’s first military engagement across the Adriatic. It places Roman decision-making and action within its proper context by emphasizing the role that Greek polities and Illyrian tribes played in both the outbreak and conclusion of the war. It argues that the primary motivation behind the Roman decision to declare war against the Ardiaei in 229 was to secure the very profitable trade routes linking Brundisium to the eastern shore of the Adriatic. It was in fact the failure of the major Greek powers to limit Ardiaean piracy that led directly to Roman intervention. In the earliest phase of trans-Adriatic engagement Rome was essentially uninterested in expansion or establishing a formal hegemony in the Greek East and maintained only very loose ties to the polities of the eastern Adriatic coast. -

Croatia Sail & Explore

- 11 DAYS / 10 NIGHTS CROATIA SAIL & EXPLORE - SPLIT --> SPLIT FOR PRICE CONTACT OUR SALES TEAM AT [email protected] | - SPLIT AIRPORT (SPU) How would you describe the summer of your dreams? Sailing & sunsets? Adventure & action? Beaches & bikinis? Look no further! You’re going to Croatia! The #1 place to be this summer, European hotspot of 2021 and the summer destination we’ve all been dreaming of! Spend your days sailing to UNESCO world heritage site, Mljet National Park, before hitting up the ultimate insta hot spot of Plitvice Lakes. Immerse yourself in the rich culture & history of Croatia by visiting Hvar and Zadar and party till the sun comes up at Pag Island. Spend 8 glorious days under the sun sailing the Adriatic before we adventure on land to see the best of the best of Croatia. 11 epic days, 10 unbelievable nights. Memories that will last forever. Crystal clear waters, golden sandy beaches and delicious Croatian cuisine. What more could you ask for? We’ve got it all... ITINERARY INCLUSIONS Day 1 - Welcome to Split! • 10 nights accommodation • All on tour transport Are you ready to kick start the most 11 epic days of your life? Hell yeah! Fly into Split Airport where we’ll pick you up and transfer you to our very own Tru Sailboat. Home for the next 8 days! Arrive any time from • Airport Transfer in Split 11am. Split is a buzzing city with so much to see and do, so take a look around, settle in to your cabin, get • Hvar island & viewpoints your sea legs on, before we grab a welcome dinner onboard in the evening. -

Hrvatski Jadranski Otoci, Otočići I Hridi

Hrvatski jadranski otoci, otočići i hridi Sika od Mondefusta, Palagruţa Mjerenja obale istoĉnog Jadrana imaju povijest; svi autori navode prvi cjelovitiji popis otoka kontraadmirala austougarske mornarice Sobieczkog (Pula, 1911.). Glavni suvremeni izvor dugo je bio odliĉni i dosad još uvijek najsustavniji pregled za cijelu jugoslavensku obalu iz godine 1955. [1955].1 Na osnovi istraţivanja skupine autora, koji su ponovo izmjerili opsege i površine hrvatskih otoka i otoĉića većih od 0,01 km2 [2004],2 u Ministarstvu mora, prometa i infrastrukture je zatim 2007. godine objavljena opseţna nova graĊa, koju sad moramo smatrati referentnom [2007].3 No, i taj pregled je manjkav, ponajprije stoga jer je namijenjen specifiĉnom administrativnom korištenju, a ne »statistici«. Drugi problem svih novijih popisa, barem onih objavljenih, jest taj da ne navode sve najmanje otoĉiće i hridi, iako ulaze u konaĉne brojke.4 Brojka 1244, koja je sada najĉešće u optjecaju, uopće nije dokumentirana.5 Osnovni izvor za naš popis je, dakle, [2007], i u graniĉnim primjerima [2004]. U napomenama ispod tablica navedena su odstupanja od tog izvora. U sljedećem koraku pregled je dopunjen podacima iz [1955], opet s obrazloţenjima ispod crte. U trećem koraku ukljuĉeno je još nekoliko dodatnih podataka s obrazloţenjem.6 1 Ante Irić, Razvedenost obale i otoka Jugoslavije. Hidrografski institut JRM, Split, 1955. 2 T. Duplanĉić Leder, T. Ujević, M. Ĉala, Coastline lengths and areas of islands in the Croatian part of the Adriatic sea determined from the topographic maps at the scale of 1:25.000. Geoadria, 9/1, Zadar, 2004. 3 Republika Hrvatska, Ministarstvo mora, prometa i infrastrukture, Drţavni program zaštite i korištenja malih, povremeno nastanjenih i nenastanjenih otoka i okolnog mora (nacrt prijedloga), Zagreb, 30.8.2007.; objavljeno na internetskoj stranici Ministarstva. -

Marine Protected Areas in Croatia

Marine protected areas in Croatia Gordana Zwicker Kompar, Institute for Environment and Nature Conservation Izola, 19th September 2019. Introduction . PA network of Croatia – national categories and Natura 2000 . Institutional framework . State of MPAs . Management effectiveness of MPAs . Ongoing projects and activities in MPAs . Key issues challenging functionality and effective management of MPAs PA network of Croatia National categories . 12,36% of inland area and 1,93% of marine area are protected in national categories % area of CATEGORY number of PAs area (km²) Croatian territory Strict Reserve 2 24,19 0,03 National Park 8 979,63 1,11 Special Reserve 77 400,11 0,45 Nature Park 11 4.350,48 4,90 Regional Park 2 1025,56 1,16 Monument of Nature 80 2,27 0,00 Significant Landscape 82 1.331,28 1,51 Park Forrest 27 29,55 0,03 Horticultural Monument 119 8,36 0,01 Total PAs in Croatia 408 7.528,05 8,55 PA network of Croatia Natura 2000 . Natura 2000 sites mostly overlaps national categories (~90%) Area of Area out of territorial sea % territorial sea territorial sea Inland area and inland sea and inland sea and inland sea Total surface of % of total No of Natura (km2) % of land waters (km2) waters waters (km2) RC (km2) surface RC 2000 sites SCI (POVS) 16.093 28,44 4.861 15,31 9,62 20.954 23,72 745 SPA (POP) 17.102 30,22 1.056 3,32 18.158 20,55 38 Natura 2000 20.772 36,7 5.164 16,26 9,62 25.936 29,36 783 PA network of Croatia Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 ‘By 2020, at least 17 % of terrestrial and inland water areas and 10 % of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved through effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas and other effective area- based conservation measures, and integrated into the wider landscape and seascape’. -

Is Mljet – Melita in Dalmatia the Island of St. Paul's Shipwreck?

Marija Buzov - Is Mljet – Melita in Dalmatia the island of... (491-505) Histria Antiqua, 21/2012 Marija BUZOV IS MLJET – MELITA IN DALMATIA THE ISLAND OF ST. PAUL’S SHIPWRECK? UDK 904:656.61.085.3>(497.5)(210.7 Mljet) Marija Buzov, Ph. D. Original scientific paper Institute of archaeology Received: 14.05.2012. Gajeva 32 Approved: 23.08.2012. 10000 Zagreb, Croatia e-mail: [email protected] naeus Pompeius’ expression Navigare necesse est, as well as mare nostrum, were created out of a simple necessity. The Romans became seafarers out of necessity, not because they had any inclination to become so, because through Ggradual spread of their authority and power to the Mediterranean coasts they were forced to learn the shipbuild- ing technique and seafaring skill from other peoples, particularly from the maritime Etruscans, Greeks and Carthaginians. The eastern Adriatic coast had been connected from prehistory, antiquity and the Middle Ages with places at the western coast of the Adriatic Sea, but also with certain areas of the Mediterranean Sea. In addition to fishing, exchange of goods and travel, the Adriatic Sea also experienced shipwrecks, as testified by a number of finds. Key-words: Mljet-Melita, Dalmatia, shipwreck, St.Paul 1 Translation: The castaway St. Paul the Apostle in the sea called the Bay of Venice, and after the shipwreck the Guest or on a Is Mljet – Melita in Dalmatia the insula vocabatur. Inspectiones anticriticae autore D. Ignatio dual interpretation of two places from the Georgio. Benedictino e congregatione Melitensi Ragusina. Acts of the Apostles in chapter XXVII, line island of St. -

My Wish: Krk to Krk 2021

Over 100 amazing cruises in Croatia Cruise from Krk to Krk with My Wish 4.9 Date From July to August (based on 4927 reviews) Duration 8 days / 7 nighs Price from 990 EUR Category Deluxe Ship My Wish details Technical specification Year of construction: 2020 | Length: 49.98m | Beam: 8.63m | Cruising speed: 10 | Cabins: 18 | Cabin sizes: N/A | Flag: Croatian Itinerary & includes for 2021. Day 1 - Saturday Krk Dinner, Welcome Reception You will be transferred from Krk airport or Krk parking to port, where embarkation begins at 15:00h. Get settled in your cabin before attending a Welcome Reception followed by dinner this evening. Itinerary & includes for 2021. Day 2 - Sunday Krk, Zadar Breakfast, Lunch Morning sail towards Zadar, swimming stop and lunch on board. Zadar has been the capital city of Dalmatia for centuries and today is the centre of North Dalmatia. It is a city with rich cultural-historical heritage, first Croatian university (founded in 1396), a city of Croatian basketball, traditional Mediterranean cuisine and unique in the world sea organ. We suggest you to join our sightseeing tour with local guide in the afternoon. Your evening is free to explore Zadar on your own. Itinerary & includes for 2021. Day 3 - Monday Zadar, Vodice, Primošten Breakfast, Lunch Morning departure towards Vodice, where you have an option to join excursion to Krka National Park (at additional cost). On way to Vodice, enjoy breakfast, swim stop on Murter Island and lunch on board. Guests who are not joining the excursion will sail to Primošten with additional swim stop. -

Croatia: Submerged Prehistoric Sites in a Karstic Landscape 18

Croatia: Submerged Prehistoric Sites in a Karstic Landscape 18 Irena Radić Rossi, Ivor Karavanić, and Valerija Butorac Abstract extend as late as the medieval period. In con- Croatia has a long history of underwater sequence, the chronological range of prehis- archaeological research, especially of ship- toric underwater finds extends from the wrecks and the history of sea travel and trade Mousterian period through to the Late Iron in Classical Antiquity, but also including inter- Age. Known sites currently number 33 in the mittent discoveries of submerged prehistoric SPLASHCOS Viewer with the greatest num- archaeology. Most of the prehistoric finds ber belonging to the Neolithic or Bronze Age have been discovered by chance because of periods, but ongoing underwater surveys con- construction work and development at the tinue to add new sites to the list. Systematic shore edge or during underwater investiga- research has intensified in the past decade and tions of shipwrecks. Eustatic sea-level changes demonstrates the presence of in situ culture would have exposed very extensive areas of layers, excellent conditions of preservation now-submerged landscape, especially in the including wooden remains in many cases, and northern Adriatic, of great importance in the the presence of artificial structures of stone Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic periods. and wood possibly built as protection against Because of sinking coastlines in more recent sea-level rise or as fish traps. Existing discov- millennia, submerged palaeoshorelines and eries demonstrate the scope for new research archaeological remains of settlement activity and new discoveries and the integration of archaeological investigations with palaeoenvi- I. R. Rossi (*) ronmental and palaeoclimatic analyses of sub- Department of Archaeology, University of Zadar, merged sediments in lakes and on the seabed.