Sculpture of Princeton University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Self-portrait Date: 1918-1920 Medium: Graphite on watermarked laid paper (with LI countermark) Size: 32 x 21.5 cm Accession: n°00776 Lender: BRUSSELS, FUNDACIÓN ALMINE Y BERNARD RUIZ-PICASSO PARA EL ARTE 20 rue de l'Abbaye Bruxelles 1050 Belgique © FABA Photo: Marc Domage PROVENANCE Donation by Bernard Ruiz-Picasso; estate of the artist; previously remained in the possession of the artist until his death, 1973 Note that: This object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Mother with a Child Sitting on her Lap Date: December 1947 Medium: Pastel and graphite on Arches-like vellum (with irregular pattern). Invitation card printed on the back Size: 13.8 x 10 cm Accession: n°11684 Lender: BRUSSELS, FUNDACIÓN ALMINE Y BERNARD RUIZ-PICASSO PARA EL ARTE 20 rue de l'Abbaye Bruxelles 1050 Belgique © FABA Photo: Marc Domage PROVENANCE Donation by Bernard Ruiz-Picasso; Estate of the artist; previously remained in the possession of the artist until his death, 1973 Note that: This object was made post-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Little Girl Date: December 1947 Medium: Pastel and graphite on Arches-like vellum. -

The Evolution of a Campus (1756-2006)

CHAPTER 3 THE EVOLUTION OF A CAMPUS (1756-2006) Princeton University has always been a dynamic institution, evolving from a two-building college in a rural town to a thriving University at the heart of a busy multifaceted community. The campus changed dramatically in the last century with the introduction of iconic “collegiate gothic” architecture and significant postwar expansion. Although the campus exudes a sense of permanence and timelessness, it supports a living institution that must always grow in pace with new academic disciplines and changing student expectations. The Campus Plan anticipates an expansion of 2.1 million additional square feet over ten years, and proposes to achieve this growth while applying the Five Guiding Principles. 1906 view of Princeton University by Richard Rummel. In this view, the original train station can be seen below Blair Hall, whose archway formed a ceremonial entrance to the campus for rail travelers. The station was moved to its current location in the 1920s. In this 1875 view, with Nassau Street in the The basic pattern of the campus layout, with foreground, Princeton’s campus can be seen rows of buildings following east-west walks Campus History occupying high ground overlooking the Stony which step down the hillside, is already clear in Brook, now Lake Carnegie, and a sweeping vista this view. Although many buildings shown here Starting as a small academic enclave in a of farms and open land which has now become were demolished over time to accommodate pastoral setting, the campus has grown the Route 1 corridor of shopping malls and office growth and changing architectural tastes, and in its 250 years to span almost 400 acres. -

Above the Immigration Wall, Walking New York

Above the Immigration Hall, Walking New York Describing the theme of her narrative relief panels mounted on a 300-foot wide space above the immigration booths, sculptor Deborah Masters emphasizes the familiar, as well as the diverse in New York. “I look at New York through a different lens, to show the many aspects that make the city so fantastic,” she said. When passengers reach the third site-specific installation, “Walking New York,” they gaze up at a startling series of 28 reliefs – each measuring 8 feet high by 10 feet wide across a space as wide as the length of a football field. The reliefs are cast in a fiberglass modified gypsum, with a depth of relief of up to six inches and a weight of some 300 pounds each. The panels are vividly painted to show scenes of people riding the subway, working on Wall Street, crossing important bridges like the Brooklyn and Manhattan and enjoying city diversions, such as parks and outdoor restaurants. The large number of murals allowed the artist to reveal the complex layers of the city – the energy generated by a parade, the fatigue of factory workers, the joy of a wedding and the colors of its many ethnic markets. “These are scenes I believe returning New Yorkers will recognize and immediately and visitors will anticipate eagerly,” said Masters. Masters attended Bryn Mawr College, where she studied with Chris Cairns and Peter Agostini, and the New York Studio School, where she studied with George Spaventa, Clement Meadmore, and Nick Carone. Following art school, she spent three years in Italy studying and working on her sculpture. -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

Princeton University Department of Intercollegiate Athletics

PRINCETON TIGERS goprincetontigers.com Princeton University Department of Intercollegiate Athletics 2014-2015 Visiting Team Guide Princeton, New Jersey Phone: 609-258-3534 Fax: (609) 258-4477 www.goprincetontigers.com 1 PRINCETON TIGERS goprincetontigers.com Table of Contents Welcome & General Information 3 Mission Statement 4 Emergency Contact Info and Athletic Trainers 5 Coaching Staff Directory 6 Athletic Department Staff Directory 8 Athletic Communications Staff 9 Directions to Princeton University 10 Directions to Princeton University Athletic Facilities 11 Princeton University Campus Map 12 Princeton University Athletic Facilities 13 Princeton University Athletic Facilities Map 14 Transportation 15 Princeton University Department of Athletics Preferred Hotel Partners 18 Princeton University Department of Athletics Preferred Dining Partners 20 2 PRINCETON TIGERS goprincetontigers.com Welcome to Princeton! America's best minds have been visiting and meeting in the Princeton region for more than 200 years. The Princeton region offers a stimulating combination of performances by nationally and internationally acclaimed theater and musical groups, museums that address every intellectual interest, as well as modern fitness centers, gourmet restaurants, bustling malls, and sports events of every form and league. All of this can be found in a region that evolved from significant events in American history and that is known for its charming old fashioned shopping villages, monuments, and beautiful parks. As you prepare for your trip, we hope you will find this guide a useful resource. It was compiled with information to assist you with your travel plans and to make your stay in Central New Jersey even more enjoyable. Please feel free to contact members of the Princeton staff if you have any additional questions or need further assistance. -

Making Doing Looking

WINTER/SPRING 2019 MAKING DOING LOOKING 2145 W. Brown Deer Rd. | Milwaukee, WI 53217 lyndensculpturegarden.org YOUNG PEOPLE For complete details and to register, visit lyndensculpturegarden.org/education The Lynden Sculpture Garden offers a unique experience of art in nature through its collection of more than 50 monumental sculptures and temporary installations sited across 40 acres of park, pond, and woodland. GARDEN & GALLERY HOURS The Lynden Sculpture Garden offers programs for young people Daily 10 am–5 pm (closed Thursdays) that integrate our collection of monumental outdoor sculpture and The sculpture garden will be closed January 1 and April 21. temporary installations with the natural ecology of park, pond, and woodland. Led by artists, naturalists, and art educators, these programs ADMISSION explore the intersection of art and nature through collaborative Adults: $9 discovery and hands-on artmaking, using all of Lynden’s 40 acres Children, students (with ID) & seniors (62+): $7 as well as its art studio to create a joyful experience. DOCENT-LED TOURS TUESDAYS IN THE GARDEN FOR For group and school tours, contact Jeremy Stepien at: [email protected] PARENTS & SMALL CHILDREN Join naturalist Naomi Cobb for outdoor play and exploration. MEMBERSHIP Tuesdays, 10:30-11:30 am January 8: Winter Patterns Members enjoy free unlimited admission to the Lynden Sculpture $10 / $8 members for one February 12: Exploring Shapes Garden as well as discounts on camps, workshops, and classes; adult and one child 4 or under. March 12: Signs of Spring $5 guest passes; and invitations to special events. Members Additional children are $4, April 30: Gardening provide critical support for our educational and public programs, extra adults pay daily admission. -

Sculptors' Jewellery Offers an Experience of Sculpture at Quite the Opposite End of the Scale

SCULPTORS’ JEWELLERY PANGOLIN LONDON FOREWORD The gift of a piece of jewellery seems to have taken a special role in human ritual since Man’s earliest existence. In the most ancient of tombs, archaeologists invariably excavate metal or stone objects which seem to have been designed to be worn on the body. Despite the tiny scale of these precious objects, their ubiquity in all cultures would indicate that jewellery has always held great significance.Gold, silver, bronze, precious stone, ceramic and natural objects have been fashioned for millennia to decorate, embellish and adorn the human body. Jewellery has been worn as a signifier of prowess, status and wealth as well as a symbol of belonging or allegiance. Perhaps its most enduring function is as a token of love and it is mostly in this vein that a sculptor’s jewellery is made: a symbol of affection for a spouse, loved one or close friend. Over a period of several years, through trying my own hand at making rings, I have become aware of and fascinated by the jewellery of sculptors. This in turn has opened my eyes to the huge diversity of what are in effect, wearable, miniature sculptures. The materials used are generally precious in nature and the intimacy of being worn on the body marries well with the miniaturisation of form. For this exhibition Pangolin London has been fortunate in being able to collate a very special selection of works, ranging from the historical to the contemporary. To complement this, we have also actively commissioned a series of exciting new pieces from a broad spectrum of artists working today. -

Press Information

PRESS INFORMATION PICASSO IN ISTANBUL SAKIP SABANCI MUSEUM, ISTANBUL 24 November 2005 to 26 March 2006 Press enquiries: Erica Bolton and Jane Quinn 10 Pottery Lane London W11 4LZ Tel: 020 7221 5000 Fax: 020 7221 8100 [email protected] Contents Press Release Chronology Complete list of works Biographies 1 Press Release Issue: 22 November 2005 FIRST PICASSO EXHIBITION IN TURKEY IS SELECTED BY THE ARTIST’S GRANDSON Picasso in Istanbul, the first major exhibition of works by Pablo Picasso to be staged in Turkey, as well as the first Turkish show to be devoted to a single western artist, will go on show at the Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul from 24 November 2005 to 26 March 2006. Picasso in Istanbul has been selected by the artist‟s grandson Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Marta-Volga Guezala. Picasso expert Marilyn McCully and author Michael Raeburn are joint curators of the exhibition and the catalogue, working together with Nazan Olçer, Director of the Sakip Sabanci Museum, and Selmin Kangal, the museum‟s Exhibitions Manager. The exhibition will include 135 works spanning the whole of the artist‟s career, including paintings, sculptures, ceramics, textiles and photographs. The works have been loaned from private collections and major museums, including the Picasso museums in Barcelona and Paris. The exhibition also includes significant loans from the Fundaciñn Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte. A number of rarely seen works from private collections will be a special highlight of the exhibition, including tapestries of “Les Demoiselles d‟Avignon” and “Les femmes à leur toilette” and the unique bronze cast, “Head of a Warrior, 1933”. -

Picasso Et La Famille 27-09-2019 > 06-01-2020

Picasso et la famille 27-09-2019 > 06-01-2020 1 Cette exposition est organisée par le Musée Sursock avec le soutien exceptionnel du Musée national Picasso-Paris dans le cadre de « Picasso-Méditerranée », et avec la collaboration du Ministère libanais de la Culture. Avec la généreuse contribution de Danièle Edgar de Picciotto et le soutien de Cyril Karaoglan. Commissaires de l’exposition : Camille Frasca et Yasmine Chemali Scénographie : Jacques Aboukhaled Graphisme de l’exposition : Mind the gap Éclairage : Joe Nacouzi Graphisme de la publication et photogravure : Mind the gap Impression : Byblos Printing Avec la contribution de : Tinol Picasso-Méditerranée, une initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris « Picasso-Méditerranée » est une manifestation culturelle internationale qui se tient de 2017 à 2019. Plus de soixante-dix institutions ont imaginé ensemble une programmation autour de l’oeuvre « obstinément méditerranéenne » de Pablo Picasso. À l’initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris, ce parcours dans la création de l’artiste et dans les lieux qui l’ont inspiré offre une expérience culturelle inédite, souhaitant resserrer les liens entre toutes les rives. Maternité, Mougins, 30 août 1971 Huile sur toile, 162 × 130 cm Musée national Picasso-Paris. Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979. MP226 © RMN-Grand Palais / Adrien Didierjean © Succession Picasso 2019 L’exposition Picasso et la famille explore les rapports de Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) à la notion de noyau familial, depuis la maternité jusqu’aux jeux enfantins, depuis l’image d’une intimité conceptuelle à l’expérience multiple d’une paternité sous les feux des projecteurs. Réunissant dessins, gravures, peintures et sculptures, l’exposition survole soixante-dix-sept ans de création, entre 1895 et 1972, au travers d’une sélection d’œuvres marquant des points d’orgue dans la longue vie familiale et sentimentale de l’artiste et dont la variété des formes illustre la réinvention constante du vocabulaire artistique de Picasso. -

Biographie De Pablo Picasso

DOSSIER DE PRESSE 1 SOMMAIRE Introduction et informations pratiques 3 Une exposition, deux ensembles thématiques 5 « Picasso Côte d’Azur » « Picasso dans la Collection Nahmad » 7 La famille Nahmad, 50 années au service de l’art 9 Présentation des Commissaires 12 Le parcours scénographique 13 La Biographie de Picasso et dates repères 16 Les séjours de Picasso sur la côte d’Azur 1920-1939 21 Imagier Presse 27 Le Grimaldi Forum 37 Les Partenaires 39 2 INTRODUCTION Cet été, le Grimaldi Forum crée l’événement en produisant l’exposition « Monaco fête Picasso », un hommage rendu à l'occasion du 40ème anniversaire de la disparition de cet artiste mondialement reconnu. La volonté du Grimaldi Forum Monaco est d’offrir un regard inédit sur sa production artistique, révélant non seulement les liens privilégiés qu’il a entretenus avec la Côte d’Azur, mais également une sélection exceptionnelle d’œuvres majeures issues d’une collection privée remarquable. Deux ensembles thématiques illustrent cette exposition à travers 160 œuvres : « Picasso Côte d'Azur » emmènera les visiteurs autour d’Antibes-Juan-les-Pins, Golfe-Juan, Mougins, Cannes, dans cette région qui a tant attiré Pablo Picasso l’été, entre 1920 et 1946, et où la lumière méditerranéenne, la mer et le littoral furent pour lui des sources directes d’inspiration. « Picasso dans la Collection Nahmad » mettra en lumière les chefs-d’œuvre de l’artiste qui occupent une place essentielle dans cette collection unique au monde, de par son importance et sa qualité, constituée par Ezra et David Nahmad durant ces cinquante dernières années. Le commissariat de l’exposition est conjointement assuré par Jean-Louis ANDRAL, Directeur du Musée Picasso d’Antibes, Marilyn McCULLY, spécialiste reconnue de Picasso, et Michael RAEBURN, écrivain qui a collaboré avec elle sur de nombreux ouvrages consacrés à Pablo Picasso. -

Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia

Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Revised Pages Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Perspectives from South Asia ASWIN PUNATHAMBEKAR AND SRIRAM MOHAN, EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS • ANN ARBOR Revised Pages Copyright © 2019 by Aswin Punathambekar and Sriram Mohan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published June 2019 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 13140- 2 (Hardcover : alk paper) ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 12531- 9 (ebook) Revised Pages Acknowledgments The idea for this book emerged from conversations that took place among some of the authors at a conference on “Digital South Asia” at the Univer- sity of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. At the conference, there was a collective recognition of the unfolding impact of digitalization on various aspects of social, cultural, and political life in South Asia. We had a keen sense of how much things had changed in the South Asian mediascape since the introduction of cable and satellite television in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We were also aware of the growing interest in media studies within South Asian studies, and hoped that the conference would resonate with scholars from various disciplines across the humanities and social sci- ences. -

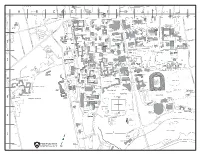

6 7 5 4 3 2 1 a B C D E F G H

LEIGH AVE. 10 13 1 4 11 3 5 14 9 6 12 2 8 7 15 18 16 206/BAYA 17 RD LANE 19 22 24 21 23 20 WITHERSPOON ST. WITHERSPOON 22 VA Chambers NDEVENTER 206/B ST. CHAMBERS Palmer AY Square ARD LANE U-Store F A B C D E AV G H I J Palmer E. House 221 NASSAU ST. LIBRA 201 NASSAU ST. NASSAU ST. MURRA 185 RY Madison Maclean Henry Scheide Burr PLACE House Caldwell 199 4 House Y House 1 PLACE 9 Holder WA ELM DR. SHINGTON RD. 1 Stanhope Chancellor Green Engineering 11 Quadrangle UNIVERSITY PLACE G Lowrie 206 SOUTH) Nassau Hall 10 (RT. B D House Hamilton Campbell F Green WILLIAM ST. Friend Center 2 STOCKTON STREET AIKEN AVE. Joline Firestone Alexander Library J OLDEN ST. OLDEN Energy C Research Blair West Hoyt 10 Computer MERCER STREET 8 Buyers College G East Pyne Chapel P.U Science Press 2119 Wallace CHARLTON ST. A 27-29 Clio Whig Dickinson Mudd ALEXANDER ST. 36 Corwin E 3 Frick PRINCETO RDS PLACE Von EDWA LIBRARY Lab Sherrerd Neumann Witherspoon PATTON AVE. 31 Lockhart Murray- McCosh Bendheim Hall Hall Fields Bowen Marx N 18-40 45 Edwards Dodge Center 3 PROSPECT FACULTY 2 PLACE McCormick AV HOUSING Little E. 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim 120 EDGEHILL STREET 80 172-190 15 11 School Robertson Fisher Finance Ctr. Colonial Tiger Art 58 Parking 110 114116 Prospect PROSPECT AVE. Garage Apts. Laughlin Dod Museum PROSPECT AVE. FITZRANDOLPH RD. RD. FITZRANDOLPH Campus Tower HARRISON ST. Princeton Cloister Charter BROADMEAD Henry 1879 Cannon Quad Ivy Cottage 83 91 Theological DICKINSON ST.