The Radiant University: Space, Urban Redevelopment, and the Public Good

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court, Appellate Division First Department

SUPREME COURT, APPELLATE DIVISION FIRST DEPARTMENT JUNE 7, 2011 THE COURT ANNOUNCES THE FOLLOWING DECISIONS: Gonzalez, P.J., Tom, Andrias, Moskowitz, Freedman, JJ. 5047 The People of the State of New York, Ind. 714/00 Respondent, -against- Bobby Perez, Defendant-Appellant. _________________________ Robert S. Dean, Center for Appellate Litigation, New York (Mark W. Zeno of counsel), for appellant. Robert T. Johnson, District Attorney, Bronx (Bari L. Kamlet of counsel), for respondent. _________________________ Judgment of resentence, Supreme Court, Bronx County (Margaret L. Clancy, J.), rendered April 23, 2010, resentencing defendant to an aggregate term of 12 years, with 5 years’ postrelease supervision, unanimously affirmed. The resentencing proceeding imposing a term of postrelease supervision was not barred by double jeopardy since defendant was still serving his prison term at that time and had no reasonable expectation of finality in his illegal sentence (People v Lingle, __ NY3d __, 2011 NY Slip Op 03308 [Apr 28, 2011]). We have considered and rejected defendant’s due process argument. Defendant’s remaining challenges to his resentencing are similar to arguments that were rejected in People v Williams (14 NY3d 198 [2010], cert denied __ US __, 131 SCt 125 [2010]). We perceive no basis for reducing the sentence. THIS CONSTITUTES THE DECISION AND ORDER OF THE SUPREME COURT, APPELLATE DIVISION, FIRST DEPARTMENT. ENTERED: JUNE 7, 2011 _______________________ CLERK 2 Tom, J.P., Friedman, Catterson, Renwick, Abdus-Salaam, JJ. 3937 The Goldman Sachs Group, Inc., Index 602060/09 Plaintiff-Appellant, Goldman, Sachs & Co., Plaintiff, -against- Almah LLC, Defendant-Respondent. _________________________ Morrison Cohen LLP, New York (Mary E. -

Home Is Where the Heart Is: the Crisis of Homeless Children and Families in New York City

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 304 228 PS 017 830 AUTHOR Mr,lnar, Janice; And Others TITLE Home Is Where the Heart Is: The Crisis of Homeless Children and Families in New York City. A Report to the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation. INSTITUTION Bank Street Coll. of Education, New York, N.Y. SI-ONS AGENCY Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, New York, N.Y. PUB DATE Mar 88 NOTE 141p. AVAILABLE FROMBank Street College of Education, 610 West 112th Street, New York, NY 10025 ($14.45, plus $2.40 handling). PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childhood Needs; *Delivery Systems; Education; *Family Problems; Futures (of Society); *Health; *Homeless People; *Nutrition; Preschool Children; Welfare Services IDENTIFIERS *New York (New York); Transitional Shelter System ABSTRACT This report on homeless children between infancy and 5 years of age highlights issues facing the 11,000 homeless children and their families living in emergency temporary housing in New York City. The rising incidence of homelessness among families is considered in national and local contexts. There follows an overview of the transitional shelter system in New York City and themany agencies serving homeless children and their families. Subsequent sections profile what is known about the health, nutrition, educatt-4, and child and family welfare of homeless chilndre. This discussion is followed by developmental descriptions of young children observed during a 6-month period at the American Red Cross Emergency Family Center. Concluding sections -

Columbia University Expansion Into West Harlem, New York City

Harlem, New York City | 143 Columbia University 06 Expansion into West Harlem, New York City Sheila Foster Harlem neighborhood, Manhattan. New York @Shutterstock York New Manhattan. Harlem neighborhood, I. BACKGROUND1 A. Columbia University’s Expansion Proposal In July 2003, Columbia University announced its thirty-year plan to build an eighteen-acre science and arts complex in West Harlem just north of its historic Morningside Heights campus and two miles south of its uptown medical center.2 Columbia’s plan would change the physical and socioeconomic layout of the target area. The plan involved massive growth of its existing campus, requiring significant re-zoning of the area targeted for construction. At the time of its announcement, Columbia already had purchased nearly half of the site and expected to acquire the other half through private sales, or from City and State agencies that owned large parcels in the proposed footprint.3 By the time that the plan was approved by the New York City Council in December 2007, Columbia controlled all but a very few properties on the proposed expansion site. Its evolving plan for the new campus had expanded to include a new business school, scientific research facilities (including laboratories), student and staff housing, and an underground gym and pool. Columbia’s announcement set in motion a complex, multi-level legal and political process which ultimately led to the project’s approval and commencement. The construction process for Columbia’s new campus continues today, as do the local tensions around its expansion into a historically low-income, ethnic minority neighborhood. 1 Much of the background on Columbia’s expansion are contained in Sheila R. -

Board of Elections the City of New York

Board of Elections The City of New York Annual Report 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 INTRODUCTION 02 COMMISSIONERS OF ELECTIONS IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK 03 MISSION STATEMENT 04 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 05 COMMISSIONERS’ PROFILES 10 COUNSEL TO THE COMMISSIONERS 10 EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT 11 SENIOR STAFF 11 BOROUGH OFFICES 13 CANDIDATE RECORDS UNIT 17 TURNOUT SUMMARY SPECIAL ELECTION – 05/05/2015 18 TURNOUT SUMMARY PRIMARY ELECTION – 09/10/2015 19 TURNOUT SUMMARY GENERAL ELECTION – 11/03/2015 20 COMMUNICATIONS AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS 22 VOTER REGISTRATION 29 ELECTION DAY OPERATIONS 41 VOTING EQUIPMENT OPERATIONS UNIT / POLL SITE MANAGEMENT 44 FACILITIES OPERATIONS 45 PROCUREMENT DEPARTMENT 46 ELECTRONIC VOTING SYSTEMS DEPARTMENT 50 PERSONNEL AND RECORDS MANAGEMENT 51 FINANCE 53 OFFICE OF THE GENERAL COUNSEL 54 MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEMS DEPARTMENT (MIS) 58 PAYROLL 59 CUSTOMER SERVICE 60 BALLOT MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT 61 APPENDIX The Board is headed by ten Commissioners, two from each borough representing both major political parties for a term of four years appointed by the New York City Council... Board of Elections The City of New York Introduction ... A similar bipartisan arrangement of over 351 deputies, clerks and other personnel ensures that no one party controls the Board of Elections. The Board appoints an executive staff consisting of an Executive Director, Deputy Executive Director and other senior staff managers charged with the responsibility to oversee the operations of the Board on a daily basis. Together, the executive and support staffs provide a wide range of electoral services to residents in Manhattan, The Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens and Staten Island. Using your Smartphone, download a FREE QR Reader. -

The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections

Guide to the Geographic File ca 1800-present (Bulk 1850-1950) PR20 The New-York Historical Society 170 Central Park West New York, NY 10024 Descriptive Summary Title: Geographic File Dates: ca 1800-present (bulk 1850-1950) Abstract: The Geographic File includes prints, photographs, and newspaper clippings of street views and buildings in the five boroughs (Series III and IV), arranged by location or by type of structure. Series I and II contain foreign views and United States views outside of New York City. Quantity: 135 linear feet (160 boxes; 124 drawers of flat files) Call Phrase: PR 20 Note: This is a PDF version of a legacy finding aid that has not been updated recently and is provided “as is.” It is key-word searchable and can be used to identify and request materials through our online request system (AEON). PR 000 2 The New-York Historical Society Library Department of Prints, Photographs, and Architectural Collections PR 020 GEOGRAPHIC FILE Series I. Foreign Views Series II. American Views Series III. New York City Views (Manhattan) Series IV. New York City Views (Other Boroughs) Processed by Committee Current as of May 25, 2006 PR 020 3 Provenance Material is a combination of gifts and purchases. Individual dates or information can be found on the verso of most items. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers. Portions of the collection that have been photocopied or microfilmed will be brought to the researcher in that format; microfilm can be made available through Interlibrary Loan. Photocopying Photocopying will be undertaken by staff only, and is limited to twenty exposures of stable, unbound material per day. -

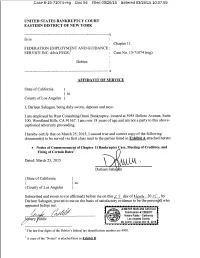

Case 8-15-71074-Reg Doc 466 Filed 08/13/15

Case 8-15-71074-reg Doc 466 Filed 08/13/15 Entered 08/13/15 11:05:33 Case 8-15-71074-reg Doc 466 Filed 08/13/15 Entered 08/13/15 11:05:33 Case 8-15-71074-reg Doc 466 Filed 08/13/15 Entered 08/13/15 11:05:33 Federation Employment and Guidance Service , Inc. dba F.E.G.S. - Service List to e-mail Recipients Served 8/7/2015 175 HEMPSTEAD, LLC 315 HUDSON, LLC AMERICAN EXPRESS TRAVEL RELATED SERVICES C PETER KOSTEAS PAT MARTIN GILBERT B WEISMAN [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BELKIN BURDEN WENIG & GOLDMAN LLP BOND, SCHOENECK & KING, PLLC BOND, SCHOENECK & KING, PLLC S. STEWART SMITH GRAYSON T. WALTER STEPHEN DONATO [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] BRONX LEBANON HOSPITAL CENTER BRYAN CAVE LLP BRYAN CAVE LLP VICTOR G. DEMARCO AARON E. DAVIS THOMAS J. SCHELL [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] CARY KANE LLP CARY KANE LLP CARY KANE LLP CHRISTOPHER BALUZY LARRY CARY LIZ VLADECK [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] DLA PIPER LLP (US) DLA PIPER LLP (US) DORMITORY AUTHORITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YO C. KEVIN KOBBE JAMILA JUSTINE WILLIS LARRY N. VOLK [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] FRIED, FRANK, HARRIS, SHRIVER & JACOBSON LLP FRIED, FRANK, HARRIS, SHRIVER & JACOBSON LLP HAMBURGER, MAXSON,YAFFE & MCNALLY, LLP GARY KAPLAN JOSEPH BUECHE LANE MAXSON [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] HAMBURGER, MAXSON,YAFFE & MCNALLY, LLP HARRIS BEACH PLLC HINSHAW & CULBERTSON LLP WILLIAM CAFFREY,JR. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 22, 2016, Designation List 490 LP-2555

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 22, 2016, Designation List 490 LP-2555 BEVERLY HOTEL (now The Benjamin Hotel), 125 East 50th Street (aka 125-129 East 50th Street; 557-565 Lexington Avenue), Manhattan. Built 1926-27; architect, Emery Roth, associate architect, Sylvan Bien Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1305, Lot 20 On July 19, 2016 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Beverly Hotel (now The Benjamin Hotel) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of the law. Six people spoke in support of designation including representatives of Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer; Manhattan Community Boards 5 and 6, the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Municipal Art Society and the Historic Districts Council. Three people spoke in opposition to designation including two representatives of the owners and the representative of the Real Estate Board of New York. In addition, the Commission received a letter from Council Member Daniel Garodnick and two e-mails from individuals in support of designation. Summary Located at the northeast corner of Lexington Avenue and East 50th Street and built in 1926-27, this 25-story (plus tower) hotel is one of the premiere hotels constructed along the noted “hotel alley” stretch of the avenue north of Grand Central Terminal. It was built as part of the redevelopment of this section of East Midtown that followed the opening of Grand Central Terminal and the Lexington Avenue subway line. -

Case 8-15-71074-Reg Doc 94 Filed 03/26/15

Case 8-15-71074-reg Doc 94 Filed 03/26/15 Entered 03/26/15 10:07:59 Case 8-15-71074-reg Doc 94 Filed 03/26/15 Entered 03/26/15 10:07:59 Case 8-15-71074-reg Doc 94 Filed 03/26/15 Entered 03/26/15 10:07:59 Federation Employment and Guidance Service , Inc. dba F.E.G.S. - U.S. Mail Served 3/25/2015 1036 REALTY LLC 1104 GAYATRI MATA LLC 118 WEST 137TH STREET LLC P.O. BOX 650 41 BAY AVENUE C/O PROSPECT MANAGEMENT CEDARHURST, NY 11516 EAST MORICHES, NY 11940 199 LEE AVENUE, #162 BROOKLYN, NY 11211 1199 NATIONAL BENEFIT FUND 1199 NATIONAL BENEFIT FUNDS FOR HEALTH 125 WEST 96TH ST. OWNERS CORP. 310 WEST 43RD STREET AND HUMAN SERVICE EMPLOYEES C/O CENTURY MANAGEMENT SERVICES, INC. NEW YORK, NY 10036 330 WEST 42ND STREET ATTN: A.J. REXHEPI NEW YORK, NY 10036 P.O. BOX 27984 NEWARK, NJ 07101-7984 1250 LLC 1256 CENTRAL LLC 14-26 BROADWAY TERRACE ASSOCIATES, LLC 7912 16TH AVENUE 1837 FLATBUSH AVENUE C/O BTH HOLDINGS LLC BROOKLYN, NY 11214 BROOKLYN, NY 11210 1324 LEXINGTON AVENUE, SUITE #245 NEW YORK, NY 10128 144TH STREET LLC 1460 CARROLL ASSOCIATES 147 CORP. 49 WEST 37TH STREET, 10TH FLOOR C/O MDAYS REALTY LLC C/O UNITED CAPITAL CORP NEW YORK, NY 10018 1437 CARROLL STREET, OFFICE ATTN: STEVE LAWRENCE, PROPERTY MGR. BROOKLYN, NY 11213 9 PARK PLACE, 4TH FLOOR GREAT NECK, NY 11021 147 CORP. 147 CORP. 1511 SHERIDAN LLC C/O UNITED CAPITAL CORP. -

Columbia NC Study.Indd

Manhattanville Neighborhood Conditions Study B. HISTORIC CONTEXT Following several decades as a commercial waterfront village consisting of stables, warehouses, ice- houses, and factories, Manhattanville developed into a thriving industrial district in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Spurred by transportation improvements in the mid-1800s, including a rail station and ferry terminal at 130th Street, the area was ideally located for quick shipment of goods to New Jersey and points north. Initially, the neighborhood attracted the dairy and meatpacking industries, which required expedient shipment for perishable goods. In the early 20th century, construction of the IRT subway system, including the Manhattan Valley IRT viaduct, created a housing boom in the Manhattanville area and a commercial corridor formed along Broadway—effectively transforming the village into the urban area it is today. While housing was developed throughout Manhattanville, the study area itself remained a manufacturing and trade-related hub in large part due to the 1916 zoning resolution that deemed the study area as “unrestricted,” thereby allowing for industrial use. When demand for automobiles increased after World War I, ample space, unrestricted zoning, and visibility from the elevated IRT subway line made Manhattanville an excellent choice for automobile service facilities. Manhattanville’s ferry and rail access was of particular importance, as cars were manufactured in the Midwest and delivered by sea and rail freight to the study area. Automobile show- -

College Voice Vol. 99 No. 10 Connecticut College

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College 2015-2016 Student Newspapers 4-4-2016 College Voice Vol. 99 No. 10 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2015_2016 Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "College Voice Vol. 99 No. 10" (2016). 2015-2016. 8. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccnews_2015_2016/8 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2015-2016 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. .. .. ... ; .. .' THE COLLEGE VOICE CONNECTICUT COLLEGE'S INDEPENDENT STUDENT NEWSPAPER Capitalism Works for Me! - But Does It? SARAH ROSE GRUSZECKI Sandy Grande describes that stu- OPINIONS EDITOR dents spent the past year examining With its gaudy twinkling letters the intersections of race, capital and blaring red scoreboard, the and capitalism. The Center had al- Capitalism Works For Me! public ways wanted to incorporate a pub- art piece currently positioned out- lic art piece into their studies, but side of Cro is tough to miss--but Grande worried that after discover- perhaps that's the point. Designed ing Lambert's work, the possibility by artist Steve Lambert to spark- of bringing it to campus would be conversation about our economic slim. However, after contacting the system, the piece has served as a artist and the current holder of the rarity in promoting these frequently art piece, The Station Museum in silenced conversations around the Houston, Texas, possibility quickly country. -

City College • St. Nicholas Park • Riverside Park • Jackie Robinson Park

H A R L Harlem / HamiltonE Heights CITY COLLEGE • ST. NICHOLAS PARK • RIVERSIDEM PARK • JACKIE ROBINSON PARK Lenox Terrace, L10 West 138 Street, J1, J7 Bronx Streets Abraham Lincoln Houses, L11, L12 Big Apple Jazz/EZ’s Woodshed, M8 Engineering, L4 First Calvary Baptist Church Harlem Hospital Center, L9 Masonic Temple, C4 Ft. Washington Post Office, B3 River Terrace, C1 St. Paul’s Community Church, G7 Washington Hts. Public Library, A4 Streets & Bridges Macombs Dam Bridge, C8 West 139 Street, J1, J7-10 Abyssinian Baptist Church, K8 Bishop James P. Roberts Learning Ctr, G8 North Academic Ct.r/Library, K4 of Harlem, F4 Harlem River Houses, D7 Mayfield Nursery School, H4 Hamilton Grange Post Office, F3 Riverbend Houses, J11 St. Philip’s Episcopal Church & West 135th St. Apartments, K8 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Cromwell Avenue, D11 The Bronx Key Macombs Place, E7 West 140 Street, J1, J7 Academy of Collaborative Education, L7 Boricua College, C2 Park Gym, M4 Frederick Douglass Academy, E8 Harlem School of the Arts, H5 Messiah’s Temple, F7 Lincolnton Post Office, J10 Riverside Park, F1 Community Center, L7 Williams Institute CME Church, M8 Boulevard, J8 East 146 Street, F12 Madison Avenue, K-L11 West 141 Street, H1-7, H10 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Museum, K8 Bread & Roses Int. Arts HS, K6 Robert E. Marshak Building,R K5 Frederick Johnson Park, E8 Harlem Village Academy, G7 Modern School, A1 Prince Hall Colonial Park Riverside Park Community Apts., L1 St. Philip’s Senior Housing, L7 Wilson Major Morris Comm. Ctr, D4 Amsterdam Avenue, B-K4 East 149 Street, F12 accessible Transit Police Madison Avenue Bridge, J12 West 142 Street, H2, H7 African American Walk of Fame, K7 Central Harlem Senior Center, J8 Shepard Hall, J5 Friendship Baptist Church , M8 Harlem YMCA, L8 Morningstar Pentecostal Chapel, L6 Child Care Center, B6 Riverton Houses, K11 St. -

Greatness the Centennial Honorees

Volume 18, Number 4, FALL 2010 ABO DEVELOPMENTS A Century of Greatness The Centennial Honorees ALSO INSIDE: Meet ABO Member MATTHEW LAPORTE Quinn and Feiner Associated Builders & Owners of Greater New York, Inc. 80 Maiden Lane, Suite 1503 New York, NY 10038 (212) 385-4949 Fax: (212) 385-1442 www.abogny.com ABOQ_0410.indd 1 10/15/10 8:01:45 AM It’s a Window–Not a Thermostat Tired of paying to heat the entire city? With oil and natural gas prices at an all time high, there’s never been a better time to look to Heat-Timer for better control of boiler systems. Heat-Timer controls help property owners effectively regulate boiler output, so tenants stay comfortable – and BTUs stay INSIDE the building where they belong. PLUS, with Heat-Timer’s Internet Control Management Systems (ICMS) and wireless space sensors, owners can monitor their buildings from anywhere, anytime. For more fuel efÀ cient solutions, call Heat-Timer today! R 20 New Dutch Lane Fairfi eld, NJ 07004 C O R P O R A T I O N 973.575.4004 www.heat-timer.com 434664_HeatTimer.inddABOQ_0410.indd 2 1 10/15/106/19/09 9:43:538:02:04 AM 495314_Boro.indd 1 9/10/10 11:57:02 AM ARE YOU READY FOR BENCHMARKING? Energy benchmarking is the LAW in NYC. Boro Energy is the solution. New York City’s Greener, Greater Buildings Plan requires that all commercial buildings over 50,000 SF undergo energy benchmarking by May 1, 2011. Boro Energy can help you beat the deadline – while using the process to improve your building’s value and profitability.