Global Economic Prospects, January 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polities of Economic Reform in Affiea

The Polities of Economic Reform in Affiea Edited by Peter Gibbon, Vusuf Bangum G, AmOfitad No. 26 titute of Mcan Studies Seminar Proceedings No. 26 AUTHORITARIANISM, DEMOCRACY, AND ADJUSTMENT The Politics of Economic Reform in Africa Edited by Peter Gibbon Yusuf Bangura Arve Ofstad Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala 1992 (The Scandinavian Institute of African Studies) Political participation Structural adjustment Cover picture: Adriaan Honcoop Typesetting: Eva Lena Volk and Grafiska ByrAn AB, Uppsala Copyediting: Sonja Johansson and Mai Palmberg O Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 1992 Printed in Sweden by Bohuslaningens Boktryckeri AB, Uddevalla, second imprint 1993. ISSN 0281- 0018 ISBN 91 -71 06-321- 8 (Hard cover) ISBN 91 -7106-323-4 (Soft cover) Contents Preface Adjustment, Authoritarianism and Democracy in Sub-Saharan Africa An Introduction to Some Conceptual and Empirical Issues Yusuf Bangura and Peter Gibbon Authoritarian Rule and Democracy in Africa A Theoretical Discourse Yusuf Bangura Empowerment or Repression? The World Bank and the Politics of African Adjustment Bjorn Beckman Interest Group Politics and the Implementation of Adjustment Policies in Sub-Saharan Africa John Toye Structural Adjustment and Pressures toward Multipartyism in Sub-Saharan Africa Peter Gibbon Stick and Carrot Political Alliances and Nascent Capitalism in Mozambique 169 Kenneth Hermele Structural Adjustment and Multiple Modes of Livelihood in Nigeria Abdul Raufu Mustapha References Notes on Contributors Abbreviations AC Africa Confidential CM1 Chr. Michelsen Institute EC European Community ECA Economic Commission for Africa ERP Economic Recovery Plan (Tanzania) FAO Food and Agricultural Organisation forex foreign exchange Frelimo Frente de LibertacBo de Mocambique FT Financial Times GDP Cross Domestic Product GLSS Ghana Living Standards Survey (1987) IF1 International financial institution(s1 [i.e. -

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/W/132 21 August

RESTRICTED WT/TPR/W/132 21 August 2017 (17-4440) Page: 1/64 Trade Policy Review Body NIGERIA DRAFT MINUTES OF THE MEETING* HELD ON 13 AND 15 JUNE 2017 Delegations are invited to submit factual corrections, if any, on their own statement to the Secretariat (Mrs Barbara Blanquart: [email protected], or to [email protected]) no later than 4 September 2017. Organe d'examen des politiques commerciales NIGÉRIA PROJET DE COMPTE RENDU DE LA RÉUNION* TENUE LES 13 ET 15 JUIN 2017 Les délégations sont invitées à soumettre leurs éventuelles corrections factuelles concernant leurs propres déclarations au Secrétariat (Mme Barbara Blanquart: [email protected], ou [email protected]) le 4 septembre 2017 au plus tard. Órgano de Examen de las Políticas Comerciales NIGERIA PROYECTO DE ACTA DE LA REUNIÓN* CELEBRADA LOS DÍAS 15 Y 17 DE JUNIO DE 2017 Las delegaciones pueden enviar a la Secretaría (Sra. Barbara Blanquart: [email protected], o [email protected]) a más tardar el 4 de septiembre de 2017 las correcciones fácticas que deseen introducir en sus propias declaraciones. _______________ * In Original language only/En langue originale seulement/En el idioma original solamente. WT/TPR/W/132 • Nigeria - 2 - TRADE POLICY REVIEW NIGERIA DRAFT MINUTES OF THE MEETING Chairperson: H.E. Mr Juan Carlos Gonzalez (Colombia) CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTORY REMARKS BY THE CHAIRPERSON ....................................................... 3 2 OPENING STATEMENT BY THE REPRESENTATIVE OF NIGERIA ..................................... 5 3 STATEMENT BY THE DISCUSSANT .............................................................................. 12 4 STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS ........................................................................................ 16 5 REPLIES BY THE REPRESENTATIVE OF NIGERIA AND ADDITIONAL COMMENTS ........ 55 6 CONCLUDING REMARKS BY THE CHAIRPERSON ........................................................ -

Petroleum and Nigeria's Economy

Research on Humanities and Social Sciences www.iiste.org ISSN (Paper)2224-5766 ISSN (Online)2225-0484 (Online) Vol.4, No.16, 2014 Petroleum and Nigeria’s Economy: A Paradox of Global Reality since 1956 PAUL, Ilesanmi Akanmidu (Ph.D Student) Department of History and International Studies Adeku nle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Ondo State, Nigeria [email protected] Abstract Petroleum, which is also known as “black gold” was discovered in commercial quantity in Nigeria in 1956. The discovery was unmistakably assumed to mark a turning point for radical economic transformation and development in Nigeria. However, over fifty years of petroleum exploration have left many people in dilemma whether it is a curse or blessing. Instead of economic progress, Nigeria seems to plummet despite the multi- millions petrodollars accruable from daily explorations. This sharply contrasts with the experiences of countries like Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Libya and Qatar among others. It is based on this background; this study takes a panoramic historical investigation into this paradox of reality considering the current trend of economic doldrums and poverty in Nigeria. The study uses historical and comparative tools of analyses to provide insight into the petroleum exploration within the nexus of two schools of thought. Keywords: Nigeria, Petroleum, Agriculture, Niger/Delta, Poverty and Corruption. Introduction Nigeria, the focus of this study is the most populous black nation and seventh in the world as a whole. According to National Population Commission of Nigeria, the population of Nigeria was estimated at One Hundred and Seventy Million (170, 000 000) people as at December, 2013 (National Population Commission 2013:3). -

The Nigerian Economy Reforms, Emerging Trends and Prospects

CPED Monograph Series No. 8 THE NIGERIAN ECONOMY REFORMS, EMERGING TRENDS AND PROSPECTS Samson Edo & Augustine Ikelegbe This Publication is supported by the Think Tank Initiative Programme initiated and managed by the International Development and Research Centre (IDRC) CPED Monograph Series 2014 i Published by Centre for Population and Environmental Development (CPED) BS-1 and SM2 Ugbowo Shopping Complex, Ugbowo Housing Estate P.O. Box 10085, Ugbowo Post Office Benin City, Nigeria (C) Samson EDO and Augustine IKELEGBE First published in 2014 Series Editor: Professor Emeritus Andrew G. Onokerhoraye Executive Director, CPED, Benin City All rights reserved. This monograph is copyright and so no part of it may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the express written permission of the publisher, and author who is the copyright owner. Printed in Nigeria by: #4, Otike-Odibi Avenue, Isiohor, Via Ugbowo Old Lagos Road, P.O. Box 5027, Benin City, Edo State. 052-880527 & 08074009192 CPED Monograph Series 2014 ii FORWARD This policy research monograph is part of the ongoing research of the Centre for Population and Environmental Development (CPED) on the research theme titled “ Growth and Equity in Nigeria” in the current strategic plan (2010-2014) of the Centre. The title of this monograph is quite germane to contemporary discourse on national development in Nigeria. The Nigerian economy has not experienced much consistent positive growth and the consequences for national development have been dire. The deterioration in the standards of living, public welfare, social service delivery and infrastructure has been extensive. -

Growth and Economic Transfor

Copyright c African Development Bank Group 2019 Rights and Permissions This document may be ordered from: All rights reserved. African Development Bank The text and data in this publication may be reproduced Nigeria Country Department as long as the source is cited. Reproduction for Plot 1521, Cadastral Zone A0 commercial purposes is forbidden. Off Memorial Close Central Business District Abuja, Nigeria Legal Disclaimer This study was prepared as part of analytical work to Phone (Standard): (+234) 9 700 2092 underpin preparation of the Country Strategy Paper (+234) 9 700 2095 (CSP) 2020-2024 for Nigeria. The study was led by Chuku Chuku and Anthony Simpasa with input from a Email: [email protected] team of staff from the Nigeria Country Department. Cover design, typesetting, interior design The views expressed herein are entirely those of the and production: KeyKoncepts Nigeria Limited authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the African Development Bank, its Boards of Directors, or the countries they represent. Growth and Economic Transformation Options for Nigeria: i An Assessment Using Growth, Identification and Facilitation Framework Preface For nearly two decades until the 2016 economic recession, Nigeria’s economy grew at average of more than 6 percent per annum. However, this growth has not been transformational as evidenced by a steady rise in unemployment and slow progress in poverty reduction. Effectively therefore, Nigeria has experienced a jobless growth. This reflects structural deficiencies of the economy, which is largely anchored on the oil sector. The federal government has initiated some policy measures aimed at transforming the economy and diversifying exports from oil and gas into sectors that have potential to create jobs. -

Nigerian Economy: Business, Governance and Investment in Period of Crisis

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Nigerian economy: business, governance and investment in period of crisis Ibrahim Abdullahi, Shafiu 23 October 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/91074/ MPRA Paper No. 91074, posted 31 Dec 2018 10:41 UTC 1 NIGERIAN ECONOMY BUSINESS, GOVERNANCE AND INVESTMENT IN PERIOD OF CRISIS SHAFIU IBRAHIM ABDULLAHI 2 Copyright © 2018 ECONOMIC ISSUES, P.O. BOX 14608 KANO-NIGERIA Text copyright © 2018 Shafiu Ibrahim Abdullahi All rights reserved. No part of this material may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means for a commercial purpose, without the prior permission of the author. 3 Contents I. Preface II. Introduction III. Inflation, growth and macro-management 1- Nigeria economic conundrum 2- Economic growth and human development 3- Inflation and public debt IV. Money, banking and finance 1- Central Banking 2- Commercial banking 3- Banking reform 4- Conventional and Islamic banks 5- Microfinance V. Capital market and foreign investment 1- Nigerian stock exchange 2- Capital market supervision 3- Effect of government policy on capital market 4- Foreign investments VI. Trade and Business management 1- Retail Business 2- Brand Building 3- Business Conglomerates 4- Entrepreneurship 5- Real Estate Business VII. Corruption, insecurity and climate change 1- Corruption and development 2- Regional development 3- Effect of insecurity on development 4- Climate change and development VIII. Women in government and business 1- Role of Women in Development 2- Women and corruption 3- Women and Entrepreneurship IX. Economics education, media and technology 1- Economics of education 2- Financial journalism 3- Advertising in Nigeria 4- Technology Startups 4 X. -

Naira - Yuan Diplomacy: a Pathway for Unlocking Nigeria’S Manufacturing Sub-Sector Potentials

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 12 No 1 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) www.richtmann.org January 2021 . Research Article © 2021 Simeon G. Nenbee and Jonah O. Orji. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Received: 18 August 2020 / Accepted: 9 October 2020 / Published: 17 January 2021 Naira - Yuan Diplomacy: A Pathway for Unlocking Nigeria’s Manufacturing Sub-Sector Potentials Simeon G. Nenbee Jonah O. Orji Department of Economics, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Port Harcourt, PMB 5323 Choba, East-West Rd, Port Harcourt, Nigeria DOI: https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss-2021-0006 Abstract The fountain head for weighing one unit of a domestic currency in-terms of another within an international framework is rooted in the famous Gold Standard proposed by the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs). This brand of thought had since been practiced and experienced in numerous trade ties that Nigeria had had with China. Like other bilateral agreements, it sets to re-define and deepen the two countries’ economic space. Thus, this paper shed lights on Naira - Yuan Diplomacy as a Pathway for Unlocking Nigeria’s Manufacturing Sub-Sector Potentials.The manufacturing industries are engines of economic prosperity. Facilitation of job creation space and poverty reducing strategies are core values in manufacturing too. This paper conclusively presume that the exchange rate pass-through mechanism can transmit price increase and macroeconomic instability from China and supply shocks to the Nigerian economy (especially from manufactured products) when adequate provisions are not domestically taken. -

Strategies of State Control of the Economy: Nationalization and Indigenization in Africa Author(S): Ernest J

Strategies of State Control of the Economy: Nationalization and Indigenization in Africa Author(s): Ernest J. Wilson III Source: Comparative Politics, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Jul., 1990), pp. 401-419 Published by: Ph.D. Program in Political Science of the City University of New York Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/421971 Accessed: 11/11/2008 17:06 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=phd. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Ph.D. Program in Political Science of the City University of New York and Ph.D. -

Diversification of Nigeria Economy Through Agricultural Production

IOSR Journal of Economics and Finance (IOSR-JEF) e-ISSN: 2321-5933, p-ISSN: 2321-5925.Volume 7, Issue 6 Ver. III (Nov. - Dec. 2016), PP 104-107 www.iosrjournals.org Diversification of Nigeria Economy through Agricultural Production Adams Oluwadamilola Kemi Department of Science and Technology National Defence College Abuja, Nigeria Abstract: There is no doubt that petroleum (crude oil) has contributed substantially to Nigerian revenue since its discovery in 1956 and more especially, since 1970 when its price was on the upward trend, it is a well-known fact that Nigeria's continuous large earnings or revenue from this sector will be impossible due to the reduction in oil price. However, it is a known fact across the globe that for a country to attain growth and development, its economy has to be diversified. Mono-economy needs to give way to the productive development of various sectors of the economy. As a matter of fact, there is an urgent need for the Nigerian government to begin looking into diversification of the economy into the agricultural sector so as to attain solid economic growth. These studies have shown that there exists a positive relationship between economic growth in Nigeria and diversification into the agricultural sector. Descriptive statistical method and correlation analysis was employed in this paper. This paper however, attempted to seek out how diversification of the economy will enhance stable and viable economic growth in Nigeria. Keywords: Economic diversification, Agricultural production I. Introduction As global oil prices continue to fall sharply over the past 18 months, Nigerians, for an economy that is largely dependent on oil needs not be told that tough times beckons. -

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY of HEALTH CARE PROBLEMS in NIGERIA by Dennis A

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF HEALTH CARE PROBLEMS IN NIGERIA by Dennis A. Ityavyar The economy of Nigeria is based on the capitalist system established by the Britisb. colonial government in the early 20th c~ntury. · Today, the Nigerian economy is sustained by the neo-colonial forces of Europe and America through International agencies and multinational companies such as Lever Brothers, Coca-Cola, World Bank, Barclays Bank International, etc. It is from these organizations and corporations that the domestic capitalist relations of production derive their operative force and support. The institutions and values of the capitalist · system now shape the productive process and consequently deter mine class structure, nature of the ·state and policy-making and implimentation in Nigeria. The class structure of a state determines the character of its social services through policy-making· and implementation. State organs responsible for the· operation of different social services are thereby directly determined by the structure of the political economy of the country in question. That is why it is important to understand the political economy of a coun try in order to appreciate the nature of its health services. The main health care problems considered here are therefore closely related to the structure of Nigeria's socio-political economy. I Class factors and the distribution of health care services The quality of services rendered to Nigerians in the pri vileged classes is much better than that of the poor. For in stance,. one doctor .serves only about 400 patients in the former, but 25,000 in the latter category. Life expectancy in.Nigeria· is 41 years for the poor~ but as high ·as 62 years for the more privileged ·classes.* · *The statistics in this section are based on estimates calculated using WHO data. -

Nigeria-China Trade Relations: Implication on the Nigerian Domestic Economy

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1697 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2847 (Online) Vol.4, No.17, 2013 Nigeria-China Trade Relations: Implication on the Nigerian Domestic Economy Tajudeen. J. AYOOLA Dept. of Management & Accounting, Faculty of Administration, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The study assesses the increased trade relations between Nigeria and China with a view to providing information on its implication on the Nigerian domestic economy through the assessment of the perceptions of local manufacturers and entrepreneurs and current trade statistics between the two countries. Data were collected from both primary and secondary sources. Primary data were sourced through the administration of questionnaire on 400 randomly selected respondents. The results showed a trade imbalance in favour of China, however, Nigeria stands to gain from the China’s model of growth and manufacturing expertise. The study concluded that the Nigerian government should encourage massive direct investment and the location of production facilities in Nigeria by the Chinese firms rather than trade relations to correct the imbalance and provide more jobs for Nigerians. Keywords: Nigeria, China, Trade, Manufacturing 1. Introduction Globalization has been defined as the process through which goods and services, capital, people, information and ideas flow across borders and lead to greater integration of economics and societies (Agenor, 2004). It seeks to remove all national barriers to the free movement of international capital and this process is accelerated and facilitated by the supersonic transformation in information technology (Tandon, 1998). It deals with the increasing breakdown of trade barriers and the increasing integration of world market; this is evident from its push of free-market economics, liberal democracy, good governance, gender equality and environmental sustainability among other holistic values; (Akindele, Gidado and Olaopa, 2002). -

Nigeria Background Report.Pdf

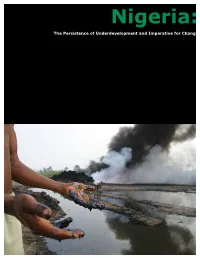

Nigeria: The Persistence of Underdevelopment and Imperative for Change Nigeria IR 322: Poverty and Development Professor Bruce Moon Lehigh University Bethlehem, PA Background Report: Nigeria ABSTRACT: Nigeria is one of the wealthier nations in the world, yet the majority of its population is strikingly poor. This report seeks to address this issue by assessing the potential for development in Nigeria. While there are numerous obstructions to development, there are also many aspects of the country that make its prospects for development promising. This report uses this assessment to develop a proposal for a development plan focused on increasing the quality and availability of primary education in Nigeria. Glen DeVillafranca Nicholas Lancaster Daniel Letts Kate McCarthy Diego Molina 1 of 84 Nigeria Table of Contents Introduction . 5 Section 1: State of Nigeria . 6 A Thriving Economy . 7 The Real Problem – Poverty . 12 Capital . 12 Employment . 14 Education . 19 Health . 28 Inequity . 32 Section 2: Cause - Why the Underdevopment? . 38 Nigeria Since Independence . 39 The Impact of Oil . 40 The Real Problem: Patron-Clientage . 45 Violence Prevents Development . 49 Violence in the Delta . 49 Violence from Ethnic Conflict . 52 Section 3: Constraints on Future Development . 56 Consolidation of Influence . 57 Social Structures . 58 Political Structure . 59 Economic Structure . 62 Section 4: Potential and Promise . 64 Fatalism – The Wrong Approach . 65 2 of 84 Nigeria Table of Contents Why Nigeria . 67 Economic and Fiscal Framework . 68 System of Governance . 68 Human Capital . 69 Young Population . 72 Section 5: How to Start the Change: A Proposal . .. 76 3 of 84 Nigeria Introduction Nigeria is a nation characterized by both problems and potential.