Bretton Woods System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region for Toll-Free Reservations 1-888-237-8642 Vol

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region FOR TOLL-FREE RESERVATIONS 1-888-237-8642 Vol. 20 No. 1 GPS: 893 White Mountain Hwy, Tamworth, NH 03886 PO Box 484, Chocorua, NH 03817 email: [email protected] Tel. 1-888-BEST NHCampground (1-888-237-8642) or 603-323-8536 www.ChocoruaCamping.com www.WhiteMountainsLodging.com Your Camping Get-Away Starts Here! Outdoor spaces and smiling faces. Fishing by the river under shade trees. These are what makes your get-away adventures come alive with ease. In a tent, with a fox, in an RV with a full utility box. Allow vacation dreams to put you, sunset, at the boat dock. Glamp with your sweetie in a Tipi, or arrive with your dogs, flop down and live-it-up, in a deluxe lodge. Miles of trails for a ramble and bike. Journey down the mile to the White Mountains for a leisurely hike. We’ve a camp store, recreation, food service, Native American lore. All you have to do is book your stay, spark the fire, and you’ll be enjoying s’mores. Bring your pup, the kids, the bikes, and your rig. Whatever your desire of camping excursion, we’ve got you covered with the push of a button. Better yet, give us a call and we’ll take care of it all. Every little things’ gonna be A-Okay. We’ve got you covered in our community of Chocorua Camping Village KOA! See you soon! Unique Lodging Camp Sites of All Types Vacation for Furry Family! Outdoor Recreation Check out our eclectic selection of Tenting, Water Front Patio Sites, Full- Fully Fenced Dog Park with Agility Theme Weekends, Daily Directed lodging! hook-up, Pull-thru – We’ve got you Equipment, Dog Beach and 5 miles of Activities, Ice Cream Smorgasbords, Tie covered! trails! Happy Pups! Dye! Come join the Summer Fun! PAGE 4, 5 & 6 PAGE 5 & 6 PAGE 2 & 20 PAGE 8 & 9 CHOCORUA CAMPING VILLAGE At Your Service Facilities & Activities • NEW! Food Service at the Pavilion! • Tax- Free “Loaded” campstore • Sparkling Pool with Chaise Lounges • 15,000sq.ft. -

A 21St-Century Bretton Woods? Global Financial Summit Hinges on China Playing a Role Once Taken by U.S

Volume 6 | Issue 11 | Article ID 2937 | Nov 01, 2008 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus A 21st-Century Bretton Woods? Global financial summit hinges on China playing a role once taken by U.S. Sebastian Mallaby A 21st-Century Bretton Woods? Global financial summit hinges on China playing a role once taken by U.S. Sebastian Mallaby As international pressures build to create a new international financial and currency order in the wake of the most severe global crisis since the 1930s, interest—and fantasy—center not only on the critical role of the United States but equally on China. China is now in the spotlight not only because of its position as a rising economic power, not only because of its The Mount Washington Hotel. site of the Bretton vast financial currency reserves in the range of Woods Conference $2 trillion, but also because of currency strategies that align the yen to the dollar to In this scene of rustic isolation, 168 statesmen keep its value low in order to maximize exports. (and one lone stateswoman, Mabel Newcomer Here Sebastian Mallaby looks back and forward of Vassar College) joined in history's most to envisage a new financial order that would celebrated episode of economic statecraft, place China at the center. Japan Focus remaking the world's monetary order to fend off another Great Depression and creating an unprecedented multinational bank, to be There wasn't much to see in Bretton Woods in focused on postwar reconstruction and July 1944, when delegates from 44 countries development. checked into the sprawling Mount Washington Hotel for the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference. -

The Mount Washington Resort at Bretton Woods Is Already Both Viable and Successful

FOREWORD Mount Washington Resort ENVISIONING SESSION OCTOBER ELEVENTH AND TWELFTH, 2006 • Bretton Woods, New Hampshire Foreword INTRODUCTORYRE-SETTING REMARKS AT THE BEGINNING OF A DOCUMENT OR BOOK, USUALLY written by someone other than the author. IN THIS INSTANCE, A PREFACE CONTAINING backgroundthe information to be reviewed by participants and presentersGold IN PREPARATIONStandard FOR AN envisioning session. An envisioning is a two-day process that stimulates all participants to visualize the future, to imagine, to picture in the mind, what this resort might become and how it will be experienced years hence. 3 RE-SETTING THE GOLD STANDARD 4 WELCOME TO THE WHITE MOUNTAINS 8 A RIVER RUNS THROUGH IT 10 A CAPSULE HISTORY 16 PLAINSPOKEN: THE APPEALS AND CHALLENGES 18 APPALACHIAN MOUNTAIN CLUB 20 AGENDA 22 PARTICIPANTS 26 PRESENTERS 27 E+S TEAM 28 HOW GRAND IS GRAND? 31 OVER THE RIVER AND THROUGH THE WOODS 35 BUYERS IN THE BACK YARD 40 THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MOUNTAIN 42 TECHNICOLOR THOUGHT-STARTERS 43 THE PARTNERS Re-setting the Gold Standard From July 1 to 24, 1944, 730 people from 44 countries gathered for the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference at the Mount Washington Hotel; their goals included finding a way to determine which disparate international currencies, each historic, were of how much value in relation to one another. They developed a new way of valuing money: the gold standard. Though financially, the gold standard is past its prime, the use of it as a phrase to denote unparalleled excellence remains. For example, when the Mount Washington Hotel opened in 1902, it set the gold standard for grand hotels and resorts. -

THE FLAVOR of the GRAND NORTH Experience North Ern N Ew Hampshire’S Culinary Delights with Th Ese Recipes TABLE of CONTENTS

THE FLAVOR OF THE GRAND NORTH Experience north ern N ew Hampshire’s culinary delights with th ese recipes TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................................3 BREAKFAST Bear Rock Adventures No-Bake Pumpkin Breakfast Bites ......................................................................................................4 Omni Mount Washington Resort Raspberry Stuffed French Toast ........................................................................................5 Rek’-Lis Brewing Company Coconut Chai Granola ...............................................................................................................6 BEVERAGES The Granite Grind Franconia Frenzy ......................................................................................................................................7 Mount Washington Cog Railway Keep ‘Em Warm! Mulled Cider ........................................................................................8 Potato Barn Antiques Cranberry Cosmo ...............................................................................................................................9 Raft NH Cowboy Coffee ......................................................................................................................................................10 BREAD/SALAD/SOUP Appalachian Mountain Club High Huts Cheese and Garlic Bread .....................................................................................11 -

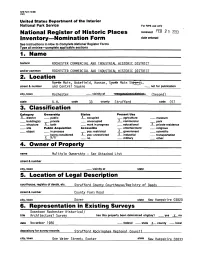

Nomination Form Date Entered 1. Name 2. Location Classif

NFS Form 10-900 (7-81) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received FEB 25 1933 Inventory — Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries— complete applicable sections 1. Name historic ________ ROCHESTER COMMERCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL HISTORIC DISTRICT and/or common ROCHESTER COMMERCIAL AND INDUSTRIAL HISTORIC DISTRICT 2. Location North Main, Wakefield, Hanson, S.wtft Main Streets., street & number ____and Central Square __________* _____________ not for publication city, town ________ Rochester _______ —— vicinity of -oongrnrrinnnl dietrict ( Second ) state M.H. code 33 county Straff ord code Q17 3. Classification Cat<egory Ownership Status Present Use X district Dublic X oeeunied aariculturp museum building(s) private . unoccupied X commercial park structure X both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Ac<:essible entertainment religious object in nrocess . yes: restricted X government Scientific being considered X yes: unrestricted X industrial transportation X N/A .no military other: 4. Owner of Property name________Multiple Ownership - See Attached List street & number city, town______________________—— vicinity of_____________state_______________ 5. Location of Legal Description______________ courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Strafford County Courthouse/Registry of Deeds_________ street & number___________County Farm Road___________________________ city,town______________Dover___________________state -

White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study

White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study June 2011 USDA Forest Service White Mountain National Forest Appalachian Mountain Club Plymouth State University Center for Rural Partnerships U.S. Department of Transportation, John A. Volpe National Transportation Systems Center Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing the burden, to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (From - To) 09/22/2011 Study September 2009 - December 2011 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER White Mountain National Forest Alternative Transportation Study 09-IA-11092200-037 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER Alex Linthicum, Charlotte Burger, Larry Garland, Benoni Amsden, Jacob 51VXG70000 Ormes, William Dauer, Ken Kimball, Ben Rasmussen, Thaddeus 5e. TASK NUMBER Guldbrandsen JMC39 5f. -

$3,699 PER PERSON • DOUBLE OCCUPANCY Non-Customers Additional $200 Per Person

$3,699 PER PERSON • DOUBLE OCCUPANCY Non-customers additional $200 per person $800 DEPOSIT DUE AT REGISTRATION FINAL PAYMENT DUE JUNE 14, 2019 Price includes: • Roundtrip ferry to Martha’s Vineyard • Round-trip transportation ~ Minneapolis airport • Visits to: Breakers Mansion, Vermont Country Store, • Non-stop air from Minneapolis to Boston Quechee Gorge, Mount Washington Cog Railway • One night in Boston; two nights at Cape Codder Resort • Kancamagus Highway autumn foliage drive NEW ENGLAND in Hyannis; one night at the Jackson Gore Inn at Okemo • M/S Mount Washington Cruise Mountain Resort; two nights at the Mountain Club at Loon; • Picture stop at Cape Neddick Lighthouse one night at the Ogunquit River Inn • Trip Insurance valued at $316* per person • 13 Meals (7 breakfasts, Grand Buffet luncheon at Mount • Bank Hosts to handle all the details • 12 meals (7 breakfasts, 1 lunch, 4 dinners) Washington Hotel, 5 dinners including a lobster bake) • Professional local guide OCTOBER 5 - 12, 2019 • Admissions per itinerary • Tours of: Historic Boston, Plymouth, Newport’s Ten • Baggage handling (one bag per person) • Baggage handling (one bag per person) Mile Coastal Drive, Mount Washington Hotel, • Tours and admissions per itinerary • Bank hosts to handle all the details. Kennebunkport & Ogunquit • Driver and guide gratuities • Travel protection is included and valued at $276 pp (To decline this option, speak with a personal banker at time of registration) • Driver and guide gratuities FIRST CITIZENS BANK Mason City • Charles City • New Hampton • Osage Clarion • Kanawha • Latimer • Mora 1-800-423-1602 TRAVEL PROTECTION: First Citizens has purchased travel protection on behalf of all travelers valued at $316pp, which is provided by Travelex Insurance. -

OMNI Mount Washington Hotel

OMNI Mount Washington Hotel Description of Host Business Housing & Boarding Information Transportation Information A grand masterpiece of Spanish Preferred International Arrival Airport: Boston, Renaissance architecture, Omni Mount MA Logan International Airport. A Concord Washington Resort in New Hampshire's Coach Line bus will take participants from White Mountains was a two-year labor of the airport to Littleton, NH. The cost for this is love for 250 master craftsmen. approx $35. Here they will be picked up by a resort representative who will take them to Omni Mount Washington Hotel is the Mount Washington by shuttle. located in Bretton Woods, New Hamp- A free shuttle goes to Wal-Mart in Littleton, shire, only 2.5 hours from Boston. NH twice a week. 200 luxury guest rooms and suites 30,000 square feet of meeting space Housing is $95/week. Dorms vary but are Full-service 25,000-square-foot spa standard Dormitory style with no formal and salon kitchen. They will be able to keep basic Recently-renovated 18-hole Donald food items and can put a small fridge in Ross designed golf course the room. The Men’s dorm has single One of the longest zip line tours in New rooms with bathrooms on each floor. Ladies England (open year round) will share with a roommate, and may Nordic Skiing and Alpine Skiing in the have an en-suite bathroom or a shared winter at Bretton Woods – New bathroom depending on the building. Hampshire’s largest ski area Premium housing is an option for Fine and casual dining including $125/week per person (rooms accommo- two Four Diamond dining rooms, the date up to two people). -

DAMAGE ASSESSMENT and RESTORATION PLAN for the OMNI MOUNT WASHINGTON RESORT #6 FUEL OIL DISCHARGE Bretton Woods, New Hampshire

Draft DARP December 2020 DRAFT DAMAGE ASSESSMENT AND RESTORATION PLAN for the OMNI MOUNT WASHINGTON RESORT #6 FUEL OIL DISCHARGE Bretton Woods, New Hampshire December 2020 Prepared by: United States Fish and Wildlife Service [i] Draft DARP December 2020 DRAFT DAMAGE ASSESSMENT AND RESTORATION PLAN FOR THE OMNI MOUNT WASHINGTON RESORT #6 FUEL OIL DISCHARGE BRETTON WOODS, NEW HAMPSHIRE Note to Reader: The following is the draft Damage Assessment and Restoration Plan (“DARP”) for the Omni Mount Washington Resort #6 Fuel Oil Discharge (the “Incident”) that occurred in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, and that was first observed on May 29, 2018. Executive Summary: This draft DARP has been prepared by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (“USFWS”), on behalf of the Department of the Interior (“DOI”), the Natural Resource Trustee (“Trustee”), to address natural resources and services injured or lost due to the release of #6 fuel oil (“Bunker C”) at or from the boiler house at the Omni Mount Washington Resort, located in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. On May 29, 2018 at 11:31am, federal and state agencies were notified of a release of #6 fuel oil from the boiler house of the Omni Mount Washington Resort in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire (“Site”). The Incident may have been ongoing since winter 2017-2018, and had been discovered in late May 2018 due to warmer weather. The oil originated from an unknown location under the boiler house and migrated to adjacent wetlands, Dartmouth Brook, and the Ammonoosuc River. New Hampshire Fish and Game (“NH F&G”) and the USFWS were notified, and New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services (“NH DES”) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“USEPA”) responded to the Incident. -

New Hampshire's Largest Ski Resort

Home Blog Articles Cartoons Contact Us New Hampshire’s Largest Ski Resort – Grandest Hotel by Peter Hines Editor Bretton Woods, New Hampshire is the setting of New Hampshire’s largest ski and snowboard resort. It is also home of the Omni Mount Washington Hotel. Together they offer arguably one of the best ski and stay experiences in the East. If you are looking for a stay in a grand hotel that is over century old, steeped in history, yet wellmaintained and cruising wide trails during the day and night the Omni Mount Washington Resort (OMWR) is the place for you. Omni Mt Washington Hotel The Mount Washington Hotel Even though Bretton Woods is the largest ski area in New Hampshire, it has a modest vertical drop of 1,500 feet. The trail and lift layout is such that one can easily traverse peaks to access almost all areas without much poling or skating. The mountain operations staff really knows how to lay down the snow and groom it with natural snow for an enjoyable experience. We found some stellar early morning corduroy on the "groomers" like Range View and Big Ben, Bigger Ben and Coos Caper. The many wide trails with gentle slopes make for a great on mountain experience. My favorite trails are Granny’s Grit and Herb’s Secret just below the top of the Zephyr Quad. If you don’t get enough runs in during the day, Bretton Woods offers night skiing off of the Bethlehem Quad. The OMWH is one of those grand hotels of a bygone era where many of the rich and famous of the late 1800s would spend their summers. -

Historic Omni Mt.Washington

Case Study HOS T® Delivers Clean Carpet 24/7 at the Historic Omni Mount Washington Resort Using HOS T Makes it Easy to Maintain this National Historic Landmark Since the summer of 1902, this beautiful resort, nestled in a valley surrounded by the White Mountains, has entertained presidents, royalty, celebrities and guests from all over the world. Traditionally it had been a summer resort but in 1999 the Mount Washington Hotel opened its doors to winter guests for the first time. Now this national historic landmark welcomes an average of 10,000 guests every The Omni Mount Washington Resort is elegant, clean and inviting. month. Railroad magnate, Joseph Stickney, who resolved to build money provide,” conceived the the hotel clean, dry and spotless. “a hotel in which nothing will hotel. Perhaps it is most famous be lacking that experience can for the 1944 Bretton Woods The 10-year-old red patterned, suggest or the liberal use of Monetary Conference that wool, Axminster carpet stretches established the World Bank and through the towering columns International Monetary Fund, of the stately lobby transporting set the gold standard at $35 an guests back to a time of romance ounce and chose the US dollar and luxury. It’s no wonder the as the backbone of international hotel earns national media exchange. recognition for its location and amenities. The 200 plus Today Suzanne Russell, guestrooms are carpeted in a Executive Housekeeper, has nylon carpet and are kept clean established her own gold standard and spotless by a dedicated and –clean and dry carpet that looks diverse housekeeping crew. -

Journal New England Ski Museum

Journal of the New England Ski Museum Spring 2015 Green Mountains, White Gold: Issue Number 96 Origins of Vermont Skiing Part 3 By Jeff Leich Photo by Walter Morrison, courtesy of Karen Lorentz Morrison, courtesy of Karen Walter Photo by The State of Vermont appropriated over a half million dollars of highway funds for construction of access roads to five fledgling ski areas in 1957. Included in that appropriation, Killington’s approach road was built in 1958 by the state, which also added $30,000 to the project for a parking lot and base lodge. Here, Preston Smith looks over construction of the access road. Vermonters had long been aware that their neighbor to the east, Hampshire, so that in 1961, that state reported that Vermont had New Hampshire, had taken a large role in the encouragement of the 60 major ski lifts, compared to 33 in New Hampshire. Of the nine fledgling ski industry in the 1930s. The ski area that New Hampshire major ski areas in New England, the top seven were in Vermont. built around an aerial tramway at Cannon Mountain was seen in Mount Snow alone had 60% of the uphill lift capacity of the Vermont chiefly as an affront to private enterprise that would stifle entire state of New Hampshire, while Mount Mansfield had 40%. future private investments in skiing. With the development of Mount Clearly, Vermont’s economic incentives for ski area development Mansfield on state forest land, Vermont established a precedent were effective. for leasing state lands for skiing, and in the 1950s that policy was expanded to include