Cloverfield the Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MICHAEL BONVILLAIN, ASC Director of Photography

MICHAEL BONVILLAIN, ASC Director of Photography official website FEATURES (partial list) OUTSIDE THE WIRE Netflix Dir: Mikael Håfström AMERICAN ULTRA Lionsgate Dir: Nima Nourizadeh Trailer MARVEL ONE-SHOT: ALL HAIL THE KING Marvel Entertainment Dir: Drew Pearce ONE NIGHT SURPRISE Cathay Audiovisual Global Dir: Eva Jin HANSEL & GRETEL: WITCH HUNTERS Paramount Pictures Dir: Tommy Wirkola Trailer WANDERLUST Universal Pictures Dir: David Wain ZOMBIELAND Columbia Pictures Dir: Ruben Fleischer Trailer CLOVERFIELD Paramount Pictures Dir: Matt Reeves A TEXAS FUNERAL New City Releasing Dir: W. Blake Herron THE LAST MARSHAL Filmtown Entertainment Dir: Mike Kirton FROM DUSK TILL DAWN 3 Dimension Films Dir: P.J. Pesce AMONGST FRIENDS Fine Line Features Dir: Rob Weiss TELEVISION (partial list) PEACEMAKER (Season 1) HBO Max DIR: James Gunn WAYS & MEANS (Season 1) CBS EP: Mike Murphy, Ed Redlich HAP AND LEONARD (Season 3) Sundance TV, Netflix EP: Jim Mickle, Nick Damici, Jeremy Platt Trailer WESTWORLD (Utah; Season 1, 4 Episodes.) Bad Robot, HBO EP: Lisa Joy, Jonathan Nolan CHANCE (Pilot) Fox 21, Hulu EP: Michael London, Kem Nunn, Brian Grazer Trailer THE SHANNARA CHRONICLES MTV EP: Al Gough, Miles Millar, Jon Favreau (Pilot & Episode 102) FROM DUSK TIL DAWN (Season 1) Entertainment One EP: Juan Carlos Coto, Robert Rodriguez COMPANY TOWN (Pilot) CBS EP: Taylor Hackford, Bill Haber, Sera Gamble DIR: Taylor Hackford REVOLUTION (Pilot) NBC EP: Jon Favreau, Eric Kripke, Bryan Burk, J.J. Abrams DIR: Jon Favreau UNDERCOVERS (Pilot) NBC EP: J.J. Abrams, Bryan Burk, Josh Reims DIR: J.J. Abrams OUTLAW (Pilot) NBC EP: Richard Schwartz, Amanda Green, Lukas Reiter DIR: Terry George *FRINGE (Pilot) Fox Dir: J.J. -

Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans

1 “Everybody Loves a Muscle Boi”: Homos, Heroes, and Foes in Post-9/11 Spoofs of the 300 Spartans Ralph J. Poole “It’s Greek to whom?” In 2007-2008, a significant accumulation of cinematic and other visual media took up a celebrated episode of Greek antiquity recounting in different genres and styles the rise of the Spartans against the Persians. Amongst them are the documentary The Last Stand of the 300 (2007, David Padrusch), the film 300 (2007, Zack Snyder), the video game 300: March to Glory (2007, Collision Studios), the short film United 300 (2007, Andy Signore), and the comedy Meet the Spartans (2008, Jason Friedberg/Aaron Seltzer). Why is the legend of the 300 Spartans so attractive for contemporary American cinema? A possible, if surprising account for the interest in this ancient theme stems from an economic perspective. Written at the dawn of the worldwide financial crisis, the fight of the 300 Spartans has served as point of reference for the serious loss of confidence in the banking system, but also in national politics in general. William Streeter of the ABA Banking Journal succinctly wonders about what robs bankers’ precious resting hours: What a fragile thing confidence is. Events of the past six months have seen it coalesce and evaporate several times. […] This is what keeps central bankers awake at night. But then that is their primary reason for being, because the workings of economies and, indeed, governments, hinge upon trust and confidence. […] With any group, whether it be 300 Spartans holding off a million Persians at Thermopylae or a group of central bankers trying to keep a global financial community from bolting, trust is a matter of individual decisions. -

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706

KATHRINE GORDON Hair Stylist IATSE 798 and 706 FILM DOLLFACE Department Head Hair/ Hulu Personal Hair Stylist To Kat Dennings THE HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Camp Sugar Director: Chris Addison SERENITY Personal Hair Stylist and Hair Designer To Anne Hathaway Global Road Entertainment Director: Steven Knight ALPHA Department Head Studio 8 Director: Albert Hughes Cast: Kodi Smit-McPhee, Jóhannes Haukur Jóhannesson, Jens Hultén THE CIRCLE Department Head 1978 Films Director: James Ponsoldt Cast: Emma Watson, Tom Hanks LOVE THE COOPERS Hair Designer To Marisa Tomei CBS Films Director: Jessie Nelson CONCUSSION Department Head LStar Capital Director: Peter Landesman Cast: Gugu Mbatha-Raw, David Morse, Alec Baldwin, Luke Wilson, Paul Reiser, Arliss Howard BLACKHAT Department Head Forward Pass Director: Michael Mann Cast: Viola Davis, Wei Tang, Leehom Wang, John Ortiz, Ritchie Coster FOXCATCHER Department Head Annapurna Pictures Director: Bennett Miller Cast: Steve Carell, Channing Tatum, Mark Ruffalo, Siena Miller, Vanessa Redgrave Winner: Variety Artisan Award for Outstanding Work in Hair and Make-Up THE MILTON AGENCY Kathrine Gordon 6715 Hollywood Blvd #206, Los Angeles, CA 90028 Hair Stylist Telephone: 323.466.4441 Facsimile: 323.460.4442 IATSE 706 and 798 [email protected] www.miltonagency.com Page 1 of 6 AMERICAN HUSTLE Personal Hair Stylist to Christian Bale, Amy Adams/ Columbia Pictures Corporation Hair/Wig Designer for Jennifer Lawrence/ Hair Designer for Jeremy Renner Director: David O. Russell -

O Marketing E O Monstro: Um Estudo Sobre O Marketing De Cloverfield

PRISMA.COM n.º 43 ISSN: 1646 - 3153 O marketing e o monstro: um estudo sobre o marketing de Cloverfield Marketing and the Monster: A Study on Cloverfield Marketing Luciano Augusto Toledo Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Brasil [email protected] Henrique Barros Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Brasil [email protected] Lucas Silva Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Brasil [email protected] Verônica Santos Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Brasil [email protected] Wilder Pinto Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Brasil [email protected] Resumo Abstract Para concorrer com grandes produções, os estúdios de To compete with major productions, low-budget Holly- Hollywood com baixo orçamento buscam investir em es- wood studios seek to invest in different strategies to pro- tratégias diferentes para promover suas produções e mote their productions and engage with their target au- engajar seu público-alvo. Dentro dessa proposta os pro- dience. Within this proposal, Cloverfield franchise pro- dutores da franquia Cloverfield desenvolveram, em ducers developed in 2008 a viral marketing-based strat- 2008, uma estratégia baseada em marketing viral. Com egy. By the Collective Subject Speech, the researchers a análise do Discurso do Sujeito Coletivo, os pesquisa- sought out to understand how this strategy was devel- dores se propuseram a entender como foi desenvolvi- oped, how it was implemented, and whether the film's vda a estratégia de marketing, como foi implementada e success was due to the implemented campaign. The re- sults obtained through qualitative analysis show that the PRISMA.COM (43) 2020, p. 170-192 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21747/16463153/43a9 170 PRISMA.COM n.º 43 ISSN: 1646 - 3153 se o sucesso do filme foi graças à campanha implemen- good results achieved by the film are due to the effi- tada. -

Development Slate the ROAD to the TOP

Development Slate THE ROAD TO THE TOP SPT has more broadcast series than ever for the 2011-2012 season (11 series) 26 SERIES Charlie’s Angels 22 SERIES Pan Am Unforgettable Happy Endings Necessary Roughness Mad Love Re-Modeled Mr. Sunshine Substitute 17 SERIES 17 SERIES 17 SERIES Plain Jane Men at Work 16 SERIES Canterbury’s Law Sit Down, Shut Up Brothers The Big C Big Day Franklin & Bash Cashmere Mafia The Unusuals Community Franklin & Bash Heist Happy Endings Power of 10 The Beast Shark Tank Pretend Time Plain Jane Kidnapped Spider-Man Newlywed Game The Sing-Off Nate Berkus The Big C 11 SERIES Rules of Engagement Viva Laughlin Judge Karen Drop Dead Diva Community Breaking In Book of Daniel Runaway Breaking Bad Rules of Engagement Hawthorne Rules of Engagement Nate Berkus Emily’s Reasons Til Death Damages Spider-Man Justified Shark Tank Community Love Monkey 10 Items or Less Judge David Young Til Death Make My Day The Sing-Off Rules of Engagement Beautiful People My Boys Rules of Engagement 10 Items or Less Dr. Oz The Boondocks Shark Tank The Boondocks Judge Maria Lopez Til Death The Boondocks Rules of Engagement Breaking Bad Greg Behrendt The Sing-Off King of Queens 10 Items or Less Breaking Bad Til Death Damages The Boondocks The Boondocks Huff The Boondocks Damages The Boondocks Drop Dead Diva Breaking Bad Rescue Me Huff My Boys My Boys Breaking Bad Hawthorne Damages Strong Medicine King of Queens Rescue Me Rescue Me Damages Justified Drop Dead Diva The Shield Rescue Me The Shield The Shield My Boys My Boys Hawthorne 2005–2006Judge Hatchett 2006–2007The Shield 2007–2008Judge Hatchett Judge2008–2009 David Young 2009–2010Rescue Me 2010–2011Rescue Me 2011–2012 Justified Judge Hatchett Judge Maria Lopez Judge Hatchett Newlywed Game Newlywed Game Rescue Me Dr. -

SBS VICELAND and SBS on Demand

WEEK 18: Sunday, 25 April - Saturday, 1 May 2021 EASTERN STATES (NSW, ACT, TAS, VIC, QLD) Start Consumer Closed Audio Date Genre Title Episode Title Series Episode TV Guide Text Country of Origin Language Year Repeat Classification Subtitles Time Advice Captions Description 2021-04-25 0500 News - Overseas Korean News Korean News 0 News via satellite from YTN Korea, in Korean, no subtitles. SOUTH KOREA Korean-100 2013 NC 2021-04-25 0530 News - Overseas Indonesian News Indonesian News 0 News via satellite from TVRI Jakarta, in Indonesian, no subtitles. INDONESIA Indonesian-100 2013 NC 2021-04-25 0610 News - Overseas Hong Kong News Hong Kong News 0 News via satellite from TVB Hong Kong, in Cantonese, no subtitles. HONG KONG Cantonese-100 2013 NC Deutsche Welle English News and analysis of the top international and European news and 2021-04-25 0630 News - Overseas Deutsche Welle English News 0 GERMANY English-100 0 NC News current affairs from Berlin, in English. 2021-04-25 0700 News - Overseas Russian News Russian News 0 News via satellite from NTV Moscow, in Russian, no subtitles. RUSSIA Russian-100 2013 NC 2021-04-25 0730 News - Overseas Polish News Polish News 0 Wydarzenia from Polsat in Warsaw via satellite, in Polish, no subtitles. POLAND Polish-100 2013 NC News from Public Broadcasting Services Limited, Malta, in Maltese, no 2021-04-25 0800 News - Overseas Maltese News Maltese News 0 MALTA Maltese-100 2013 NC subtitles. News via satellite from public broadcaster MRT in Skopje, in 2021-04-25 0830 News - Overseas Macedonian News Macedonian News 0 MACEDONIA Macedonian-100 2013 NC Macedonian, no subtitles. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

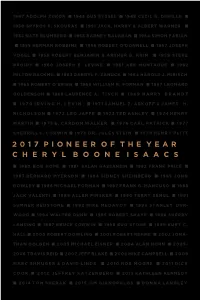

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner. -

The Participatory Networks of 9/11 Media Culture

The Politics of Ethical Witnessing: The Participatory Networks of 9/11 Media Culture A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Emanuelle Wessels IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Adviser: Ronald Walter Greene September 2010 © Emanuelle Wessels 2010 Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my advisor, Ronald Walter Greene. Professor Greene consistently went above and beyond to guide me through this project, and his insight, patience, and encouragement throughout the process gave me the motivation and inspiration to see this dissertation to the end. Thank you for everything, Ron. Thank you to Professors Laurie Ouellette, Cesare Casarino, and Gilbert Rodman for conversing with me about the project and providing helpful and thoughtful suggestions for future revisions. I would also like to thank Professor Mary Vavrus for serving on my committee, and for assisting me with crucial practical and administrative matters. Professor Edward Schiappa, whose pragmatic assistance has also been much appreciated, has been invaluably supportive and helpful to me throughout my graduate career. I would also like to acknowledge the many professors who have inspired me throughout the years, including Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, Donald Browne, Thomas Pepper, Elizabeth Kotz, Greta Gaard, and Richa Nagar. Without the kindness and friendship of the many wonderful people I have had the pleasure of meeting in graduate school, none of this would have been possible either. A heartfelt thank you to my friends, including Julie Wilson, Joseph Tompkins, Alyssa Isaacs, Carolina and Eric Branson, Kate Ranachan, Matthew Bost, Kaitlyn Patia, Alice Leppert, Anthony Nadler, Helen and Justin Parmett, Thomas Johnson, and Rebecca Juriz. -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Jay O'connell

JAY O’CONNELL Producer / UPM I MOM SO HARD (multi-cam pilot; UPM) – CBS/WBTV; Prods: Michelle Nader, Rob Thomas, Kristin Hensley, Jen Smedley; Dir: Don Scardino; w/ Freddie Prinze, Jr, David Fynn LIVING BIBLICALLY (multi-cam series; UPM) – CBS/WBTV; Prods: Patrick Walsh, Johnny Galecki, Spencer Medof, Andrew Haas; Dir: Andy Ackerman; w/ Jay Ferguson, Ian Gomez, David Krumholtz RELATIVELY HAPPY (multi-cam pilot; UPM) – CBS/WBTV; Prods: Max Mutchnick, Jeff Astrof; Dir: James Burrows; w/ Jane Lynch, Genevieve Angelson, Jon Rudnitsky, Stephen Guarino TWO BROKE GIRLS (multi-cam pilot and series, Co-Producer/UPM) – CBS / WBTV; Prods: Michael Patrick King, Whitney Cummings; Dir: Jim Burrows, Ted Wass, Scott Ellis, John Fortenberry, Fred Savage, Julie Anne Robinson, Thomas Kail, Michael McDonald, Don Scardino; w/ Kat Dennings, Beth Behrs MAN WITH A PLAN (multi-cam pilot; UPM) – CBS/CBSP; Prods: Jackie Filgo, Jeff Filgo, Michael Rotenberg, Matt LeBlanc; Dir: James Burrows; w/ Matt LeBlanc, Jenna Fischer, Grace Kaufman HAPPY LIFE (multi-cam pilot, UPM) – CBS / WBTV; Prods: Bill Wrubel; Dir: James Burrows; w/ Steven Weber, Duane Martin, Eric Petersen, Rita Moreno, Bill Smitrovich, Minnie Driver ONE BIG HAPPY (multi-cam pilot and series, UPM) – NBC/WBTV; Prods: Ellen DeGeneres, Liz Feldman, Jeff Kleeman; Dir: Scott Ellis; w/ Nick Zano, Elisha Cuthbert BIG BANG THEORY (multi-cam series, UPM) – CBS/WBTV; Prods: Chuck Lorre, Lee Aronsohn, Bill Prady; Dir: Mark Cendrowski; w/ Johnny Galecki, Jim Parsons, Kaley Cuoco, Simon Helberg, Kunal Nayyar PARTNERS -

For Incentives, Programming and More Visit: Sho.Com/Bulk

Adventurous, unexpected, hilarious, thrilling and raw, we have become known for programming that pushes boundaries, elicits emotional reactions, and always surprises. HOMELAND BILLIONS SHAMELESS Emmy® and Golden Globe® winners Paul Giamatti and WILLIAM H. MACY and EMMY ROSSUM star in this wildly Emmy®, SAG and Golden Globe® winner CLAIRE Damian Lewis star in BILLIONS – a bold drama that engaging and fearlessly twisted series – an ensemble DANES stars as the brilliant Carrie Mathison, who gives secret access into the lives of two powerful New comedy with a family like you’ve never seen before. will stop at nothing to keep America safe. The York titans. Tenacious US Attorney Chuck Rhoades When dad, Frank (MACY) is not at the bar, he’s stirring award-winning and critically acclaimed series is (GIAMATTI) is locked in a battle with brilliant hedge up trouble – so it’s a good thing he has Fiona (ROSSUM), an addicting thrill ride of action and espionage fund king Bobby ‘Axe’ Axelrod (LEWIS) and there is no his eldest daughter who keeps the family together. The that keeps you guessing at every turn. line they won’t cross to win. It’s a high stakes war Gallaghers may not have much in the way of money Stars CLAIRE DANES, RUPERT FRIEND, where both men are forced to answer the question: or rules, but they know who they are – and they’re F. MURRAY ABRAHAM.and MANDY PATINKIN. What is power worth? absolutely, wildly and unapologetically SHAMELESS. Stars PAUL GIAMATTI and DAMIAN LEWIS. Stars WILLIAM H. MACY and EMMY ROSSUM. THE AFFAIR RAY DONOVAN MASTERS OF SEX Golden Globe® nominee MICHAEL SHEEN and EMMY® The 2015 Golden Globe® winner for Best Television In the glamorous, over-indulgent world of Hollywood, nominee LIZZY CAPLAN star in this provocative true story Series—Drama, THE AFFAIR is a relationship drama Ray Donovan (LIEV SCHREIBER) discreetly arranges chronicling the controversial work, scandalous romance that unfolds like a thriller, taking you down unexpected and conveniently erases all the dirty little secrets and groundbreaking discoveries of Dr.