Refugee Protection and Human Trafficking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: an Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A

Penn State International Law Review Volume 23 Article 15 Number 4 Penn State International Law Review 5-1-2005 International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A. Yasmine Rassam Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr Recommended Citation Rassam, A. Yasmine (2005) "International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach," Penn State International Law Review: Vol. 23: No. 4, Article 15. Available at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/psilr/vol23/iss4/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Penn State International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Articles I International Law and Contemporary Forms of Slavery: An Economic and Social Rights-Based Approach A. Yasmine Rassam* I. Introduction The prohibition of slavery is non-derogable under comprehensive international and regional human rights treaties, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights'; the International Covenant on Civil and * J.S.D. Candidate, Columbia University School of Law. LL.M. 1998, Columbia University School of Law; J.D., magna cum laude, 1994, Indiana University, Bloomington; B.A. 1988, University of Virginia. I would like to thank the Columbia Law School for their financial support. I would also like to thank Mark Barenberg, Lori Damrosch, Alice Miller, and Peter Rosenblum for their comments and guidance on earlier drafts of this article. I am grateful for the editorial support of Clara Schlesinger. -

Migrant Smuggling to Canada

Migrant Smuggling to Canada An Enquiry into Vulnerability and Irregularity through Migrant Stories The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. _____________________________ Publisher: International Organization for Migration House No. 10 Plot 48 Osu-Badu Road/Broadway, Airport West IOM Accra, Ghana Tel: +233 302 742 930 Ext. 2400 Fax: +233 302 742 931 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.iom.int Cover photo: An Iraqi refugee who did not want to have his identity revealed stands in Istanbul's commercial district of Gayrettepe during afternoon rush hour. Istanbul districts, such as Aksaray and Beyoglu have been refugee transit hubs since at least the 1979 Iranian Revolution, with subsequent waves including Afghans, Africans, Iraqis and now Syrians. © Iason Athanasiadis, 2017. Recommended citation: International Organization for Migration (IOM)/Samuel Hall, Migrant Smuggling to Canada – An Enquiry into Vulnerability and Irregularity through Migrant Stories, IOM, Accra, Ghana, 2017. -

Contemporary Slavery and Its Definition In

Contemporary Slavery 2 and Its Definition in Law Jean Allain Had Olaudah Equiano, Abraham Lincoln, or William Wilberforce been able to look into the future to the twenty-first century, what they may have been most struck by was not how far we had come in ending slav- ery and suppressing human exploitation but, rather, that we had yet to agree on what in fact the term “slavery” means. This is a rather intrigu- ing puzzle, as a consensus has existed for more than eighty-five years among states as to the legal definition of slavery. Yet, this definition has failed to take hold among the general public or to “speak” to those in- stitutions interested in the ending of slavery. At first blush, this is not so hard to understand since the definition, drafted in the mid-1920s by legal experts, is rather opaque and seems to hark back to a bygone era. The definition found in the 1926 Slavery Convention reads: “Slavery is the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership is exercised.”1 At first sight, the definition really does not convey much to the reader, but for the fact that it appears to require that a person own another. As the ownership of one person by another has been legislated out of existence – again – it appears that this definition would have no traction in the contemporary world. Yet, this is not so since the legal definition of slavery established in 1926 has been confirmed twice: first, by being included in substance in the 1956 Supplementary Convention Contemporary Slavery -

The Child's Right to Participation – Reality Or Rhetoric? 301 Pp

The Child’s Right to Participation – Reality or Rhetoric? The Child’s Right to Participation – Reality or Rhetoric? Rebecca Stern Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Grotiussalen, Uppsala, Friday, September 22, 2006 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Laws. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Stern, R. 2006. The Child's Right to Participation – Reality or Rhetoric? 301 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-506-1891-1. This dissertation examines the child’s right to participation in theory and practice within the context of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and other international human rights instruments. Article 12 of the Convention establishes the right of the child to express views and to have those views respected and properly taken into consideration. The emphasis of the study is on the democracy aspects of child participation and on how the implementation of the right to participation could become more effective. For these purposes, the theoretical underpinnings of the child’s right to participation are examined with a particular focus on the impact of power structures. In order to clarify how state parties to the Convention have implemented article 12 and the way they argue regarding possible obstacles for implementation, jurisprudence and case law (practice) of the Committee on the Rights of the Child, as well as supervisory bodies of other international human rights instruments, are studied. In particular, the importance of traditional attitudes towards children on the realisation of participation rights for children is analysed. The case of India is presented as an example of how a state party to the Convention can argue on this matter. -

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery

Unfree Labor, Capitalism and Contemporary Forms of Slavery Siobhán McGrath Graduate Faculty of Political and Social Science, New School University Economic Development & Global Governance and Independent Study: William Milberg Spring 2005 1. Introduction It is widely accepted that capitalism is characterized by “free” wage labor. But what is “free wage labor”? According to Marx a “free” laborer is “free in the double sense, that as a free man he can dispose of his labour power as his own commodity, and that on the other hand he has no other commodity for sale” – thus obliging the laborer to sell this labor power to an employer, who possesses the means of production. Yet, instances of “unfree labor” – where the worker cannot even “dispose of his labor power as his own commodity1” – abound under capitalism. The question posed by this paper is why. What factors can account for the existence of unfree labor? What role does it play in an economy? Why does it exist in certain forms? In terms of the broadest answers to the question of why unfree labor exists under capitalism, there appear to be various potential hypotheses. ¾ Unfree labor may be theorized as a “pre-capitalist” form of labor that has lingered on, a “vestige” of a formerly dominant mode of production. Similarly, it may be viewed as a “non-capitalist” form of labor that can come into existence under capitalism, but can never become the central form of labor. ¾ An alternate explanation of the relationship between unfree labor and capitalism is that it is part of a process of primary accumulation. -

Out of Sight: Modern Slavery in Pacific Supply Chains of Canned Tuna

Out of Sight: Modern Slavery in Pacific Supply Chains of Canned Tuna A SURVEY & ANALYSIS OF COMPANY ACTION 02 Out of Sight: Modern Slavery in Pacific Supply Chains of Canned Tuna Table of Contents 03 Executive Summary 07 Company Evaluation 08 Company Survey 09 Context: Pacific Tuna Industry ▌ Fishing in the Pacific ▌ Drivers of Abuse ▌ Fishing Industry Practices ▌ Workforce Characteristics ▌ Legal Standards in the Fishing Industry ▌ Multi-Stakeholder Initiatives 15 Survey Findings ▌ Policies & Public Human Rights Commitments ▌ Due Diligence & Supply Chain Awareness ▌ Practical Actions to Address Modern Slavery in Supply Chains ▌ Remediation, Grievance Mechanisms & Reported Complaints ▌ Overcoming Obstacles ▌ External Stakeholder Engagement 23 Conclusion 25 Appendix: Company Responses & Non-Responses Out of Sight: Modern Slavery in Pacific Supply Chains of Canned Tuna 03 Executive Summary The Pacific is home to the world’s largest tuna fisheries, providing almost 60% of the world’s tuna catch, worth US$22 billion (out of US$42 billion globally) in 2016, and demand is growing. Yet reports of severe human rights abuses, including forced labour, slavery, human trafficking and child labour, are rife. Modern slavery is endemic in this industry, where the tuna supply chain is remote, complex and opaque. Few stories leak out about conditions but, when they do, they are often horrendous: with migrant workers bought and sold as unpaid slaves, and tossed overboard if they complain or get injured. In this context of abuse, the buyers – canned tuna companies and supermarkets – have an obligation to ensure their supply chains are not infested with slavery. Increasingly, they also have legal obligations under UK and Australian modern slavery laws. -

Key Elements of the ILO Standards on Forced Labour

Key elements of the ILO standards on forced labour The ILO has adopted four instruments on forced labour: two conventions and a protocol, which are legally binding and open to ratification, and a recommendation which provides practical guidance. The main provisions of the three binding instruments are listed below. Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29) Article 1 1. Each Member of the International Labour Organisation which ratifies this Convention undertakes to suppress the use of forced or compulsory labour in all its forms within the shortest possible period. Article 2 1. For the purposes of this Convention the term forced or compulsory labour shall mean all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily. 2. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this Convention, the term forced or compulsory labour shall not include-- a. any work or service exacted in virtue of compulsory military service laws for work of a purely military character; b. any work or service which forms part of the normal civic obligations of the citizens of a fully self-governing country; c. any work or service exacted from any person as a consequence of a conviction in a court of law, provided that the said work or service is carried out under the supervision and control of a public authority and that the said person is not hired to or placed at the disposal of private individuals, companies or associations; d. any work or service exacted in cases of emergency, that is to say, in the event of war or of a calamity or threatened calamity, such as fire, flood, famine, earthquake, violent epidemic or epizootic diseases, invasion by animal, insect or vegetable pests, and in general any circumstance that would endanger the existence or the well-being of the whole or part of the population; e. -

Analysis of the Definition of Trafficking in Human Beings in the Palermo Protocol

Analysis of the definition of trafficking in human beings in the Palermo Protocol October 2005 Marjan Wijers (LL.M, MA) Table of content General introduction Part I The Palermo Protocol 1. Introduction 2. Definition of trafficking in human beings in the Palermo Protocol 3. Background 4. The concept of “exploitation” 5. Relation between trafficking in human beings and prostitution 5.1 The concept of forced prostitution: can prostitutes be trafficked? 6. The issue of consent 7. Relation between trafficking in human beings and smuggling 8. Relation between trafficking in human beings and the forced labour or slavery-like outcomes of trafficking 9. Relation with the parent Convention: the crossing of borders and the involvement of organised crime 10. Intent, attempting, participating, organising and directing 11. Definition of victim Part II Explanation of the different elements of the definition 1. Introduction 2. The “acts” 3. The “means” 3.1 The issue of consent 4. The “purposes”: the concept of exploitation Exploitation of the prostitution of others and sexual exploitation Removal of organs Illegal adoption Part III Interpreting the Protocol: meaning and interpretation of the various prohibitions on forced labour, slavery and related practices 1. Introduction 2. Universal Declaration on Human Rights, 1948 2 3. Slavery Convention, 1926, amended by Protocol, 1953 4. UN Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery, the Slave Trade and Practices similar to Slavery, 1956 5. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), 1966 6. ILO Conventions on Forced Labour No. 29, 1930, and No. 105, 1957 7. Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989 8. -

Irregular Migration, Trafficking and Smuggling of Human Beings in EU Law and Policy

This book examines the treatment of irregular migration, trafficking and smuggling of human beings in EU law and policy. What are the policy dilemmas encountered in efforts to criminalise irregular migration and humanitarian assistance to irregular immigrants ? The various contributions in this edited Irregular Migration, volume examine the principal considerations that make up EU policies directed towards irregular migration and its relationship with trafficking and smuggling of human beings. This book aims Trafficking and to provide academic input to informed policy-making in the next phase of the European Agenda on Migration. smuggling of human beings Policy Dilemmas in the EU Centre for European Policy Studies 1 Place du Congrès 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel : 32(0)2.229.39.11 Fax : 32(0)2.219.41.51 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.ceps.eu IRREGULAR TRAFFICKING MIGRATION, OF HUMAN ANDBEINGS SMUGGLING Edited by Sergio Carrera CEPS Elspeth Guild IRREGULAR MIGRATION, TRAFFICKING AND SMUGGLING OF HUMAN BEINGS IRREGULAR MIGRATION, TRAFFICKING AND SMUGGLING OF HUMAN BEINGS POLICY DILEMMAS IN THE EU EDITED BY SERGIO CARRERA AND ELSPETH GUILD FOREWORD BY MATTHIAS RUETE CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY STUDIES (CEPS) BRUSSELS The Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) is an independent policy research institute in Brussels. Its mission is to produce sound policy research leading to constructive solutions to the challenges facing Europe. The views expressed in this book are entirely those of the authors and should not be attributed to CEPS or any other institution with which they are associated or to the European Union. This book falls within the framework of FIDUCIA (New European Crimes and Trust-based Policy), a research project financed by the European Commission under the Seventh Framework Programme, which ran from 2012-15. -

Country Baseline Under the Ilo Declaration Annual Review (2008)1: Brunei Darussalam

COUNTRY BASELINE UNDER THE ILO DECLARATION ANNUAL REVIEW (2008)1: BRUNEI DARUSSALAM THE ELIMINATION OF ALL FORMS OF FORCED OR COMPULSORY LABOUR (FL) REPORTING Fulfillment of YES, under the 2008 Annual Review (AR). Government’s reporting obligations Involvement of YES, according to the Government: Involvement of the employers’ organizations (the National Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Employers’ and Workers’ NCCI) and workers’ organizations (the Brunei Oilfield Workers Union, BOWU) by means of consultation and communication of a organizations in the copy of the Government’s report and country baseline. reporting process OBSERVATIONS BY THE Employers’ organizations 2008 AR: Observations by the NCCI and its three affiliates. SOCIAL PARTNERS Workers’ organizations 2008 AR: Observations by the BOWU EFFORTS AND PROGRESS Brunei Darussalam has ratified neither the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29) (C.29) nor the Ratification status MADE IN REALIZING THE Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105) (C.105). PRINCIPLE AND RIGHT Ratification YES, for both C.29 and C.105. Ratification intention 2008 AR: The Government indicated its intention to ratify C. 29 and C.105. The BOWU and the NCCI supported the ratification of these two Conventions by Brunei Darussalam. Recognition of the Constitution NO principle and right (prospect(s), means of Legislation action, basic legal provisions) The Penal Code (CAP 22); Policy, legislation The Women and Girls Protection Act (CAP 120); and/or regulations ) The Children Order, 2000; The Trafficking and Smuggling of Persons Order, 2004; Employment Agencies Order, 2004; and The Children and Young Persons Order, 2006 (will repeal the Children’s Order, 2000 once it is in force). -

Creating an Effective Coalition to Achieve SDG 8.7

CHRI 2018 REPORT CREATING AN EFFECTIVE COALITION TO ACHIEVE SDG 8.7 A REPORT of the International Advisory Commission of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative Chaired by Professor Yash Ghai Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative The Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan, international non-governmental organisation, mandated to ensure the practical realisation of human rights in the countries of the Commonwealth. In 1987, several Commonwealth professional associations founded CHRI, with the conviction that there was little focus on the issues of human rights within the Commonwealth although the organisation provided member countries a shared set of values and legal principles from which to work. CHRI’s objectives are to promote awareness of and adherence to the Commonwealth Harare Principles, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other internationally recognised human rights instruments, as well as domestic instruments supporting human rights in Commonwealth member states. Through its reports and periodic investigations, CHRI continually draws attention to progress and setbacks to human rights in Commonwealth countries. In advocating for approaches and measures to prevent human rights abuses, CHRI addresses the Commonwealth Secretariat, member Governments and civil society associations. Through its public education programmes, policy dialogues, comparative research, advocacy and networking, CHRI’s approach throughout is to act as a catalyst around its priority issues. CHRI is headquartered in New Delhi, India, and has offices in London, UK and Accra, Ghana. International Advisory Commission: Yashpal Ghai - Chairperson. Members: Lord Carlile of Berriew, Alison Duxbury, Wajahat Habibullah, Vivek Maru, Edward Mortimer, Sam Okudzeto, and Sanjoy Hazarika. Executive Committee (India): Wajahat Habibullah – Chairperson. -

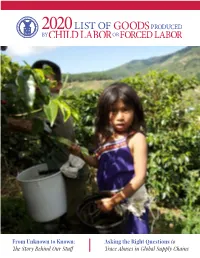

2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor Or Forced Labor

From Unknown to Known: Asking the Right Questions to The Story Behind Our Stuff Trace Abuses in Global Supply Chains DOWNLOAD ILAB’S COMPLY CHAIN AND APPS TODAY! Explore the key elements Discover of social best practice COMPLY CHAIN compliance 8 guidance Reduce child labor and forced systems 3 labor in global supply chains! 7 4 NEW! Explore more than 50 real 6 Assess risks Learn from world examples of best practices! 5 and impacts innovative in supply chains NEW! Discover topics like company responsible recruitment and examples worker voice! NEW! Learn to improve engagement with stakeholders on issues of social compliance! ¡Disponible en español! Disponible en français! Check Browse goods countries' produced with efforts to child labor or eliminate forced labor 1,000+ pages of research in child labor the palm of your hand! NEW! Examine child labor data on 131 countries! Review Find child NEW! Check out the Mexico laws and labor data country profile for the first time! ratifications NEW! Uncover details on 25 additions and 1 removal for the List of Goods! How to Access Our Reports We’ve got you covered! Access our reports in the way that works best for you. On Your Computer All three of the U.S. Department of Labor’s (USDOL) flagship reports on international child labor and forced labor are available on the USDOL website in HTML and PDF formats at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor. These reports include Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, as required by the Trade and Development Act of 2000; List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, as required by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005; and List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor, as required by Executive Order 13126.