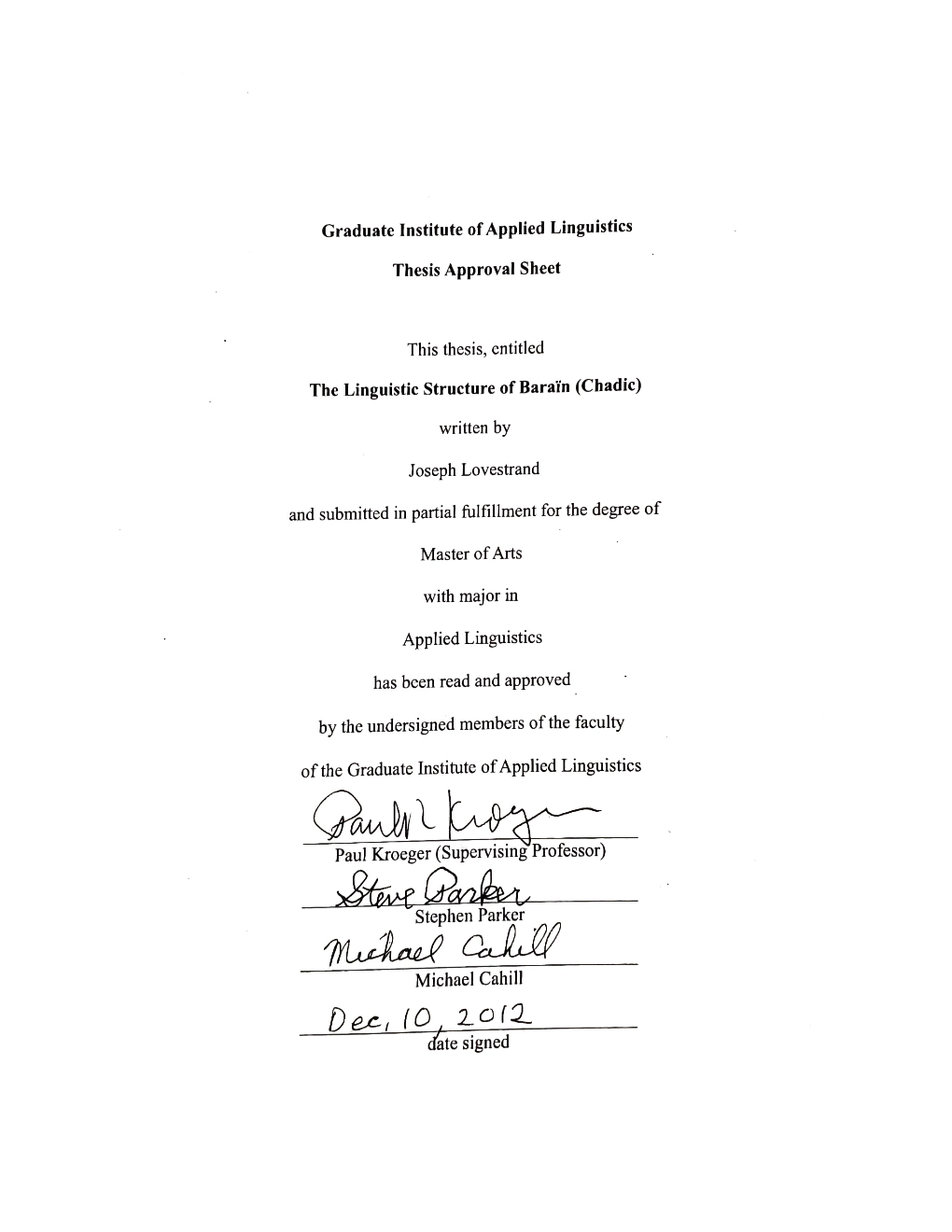

The Linguistic Structure of Baraïn (Chadic)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T3 Sandhi Rules of Different Prosodic Hierarchies

T3 Sandhi rules of different prosodic hierarchies Abstract This study conducts acoustic analysis on T3 sandhi of two characters across different boundaries of prosodic hierarchies. The experimental data partly support Chen (2000)’s view about sandhi domain that “T3 sandhi takes place obligatorily within MRU”, and “sandhi rule can not apply cross intonation phrase boundary”. Nonetheless, the results do not support his claim that “there are no intermediate sandhi hierarchies between MRU and intonation phrase”. On the contrary, it is found that, although T3 sandhi could occur across all kinds of hierarchical boundaries between MRU and intonation phrase, T3 sandhi rules within a foot (prosodic word), or between foots without pause, or between pauses without intonation (phonology phrase) are very different in terms of acoustic properties. Furthermore, based on the facts that (1) T3 sandhi could occur cross boundary of pauses and (2) phrase-final sandhi could be significantly lengthening, it is argued that T3 sandhi is due to dissimilation of low tones, rather than duration reduction within MRU domain. It is also demonstrated that tone sandhi and prosodic hierarchies may not be equivalently evaluated in Chinese phonology. Prosodic hierarchies are determined by pause and lengthening, not by tone sandhi. Key words: tone sandhi; prosodic hierarchies; boundary; Mandarin Chinese 1 Introduction So-called T3 sandhi in mandarin Chinese has been widely discussed in Chinese Phonology. Mandarin Chinese has four tones: T1 (level 55), T2 (rising 35), T3 (low-rise 214), T4 (falling 51).Generally, when a T3 is followed by another T3, it turns into T2. The rule could be simply stated as: 214->35/ ___214. -

The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology Phonology – the study of how the sounds of speech are represented in our minds – is one of the core areas of linguistic theory, and is central to the study of human language. This state-of-the-art handbook brings together the world’s leading experts in phonology to present the most comprehensive and detailed overview of the field to date. Focusing on the most recent research and the most influential theories, the authors discuss each of the central issues in phonological theory, explore a variety of empirical phenomena, and show how phonology interacts with other aspects of language such as syntax, morph- ology, phonetics, and language acquisition. Providing a one-stop guide to every aspect of this important field, The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology will serve as an invaluable source of readings for advanced undergraduate and graduate students, an informative overview for linguists, and a useful starting point for anyone beginning phonological research. PAUL DE LACY is Assistant Professor in the Department of Linguistics, Rutgers University. His publications include Markedness: Reduction and Preservation in Phonology (Cambridge University Press, 2006). The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology Edited by Paul de Lacy CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521848794 © Cambridge University Press 2007 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

Turkish Vowel Harmony: Underspecification, Iteration, Multiple Rules

Turkish vowel harmony: Underspecification, iteration, multiple rules LING 451/551 Spring 2011 Prof. Hargus Data • Turkish data on handout. [a] represents a low back unrounded vowel (more standardly [ɑ]). Morphological analysis and morpheme alternants • Words in Turkish – root alone – root followed by one or two suffixes • Suffixes – plural suffix, -[ler] ~ -[lar] – genitive suffix, -[in] ~ -[un] ~ -[ün] ~ -[ɨn] • Order of morphemes – root - plural - genitive Possible vowel features i ɨ u ü e a o ö high + + + + - - - - low - - - - - + - - back - + + - - + + - front + - - + + - - + round - - + + - - + + Distinctive features of vowels i ɨ u ü e a o ö high + + + + - - - - back - + + - - + + - round - - + + - - + + ([front] could be used instead of [back].) Values of [low] are redundant: V -high [+low] +back -round Otherwise: V [-low] Distribution of suffix alternants • Plural suffix – -[ler] / front vowels C(C) ___ – -[lar] / back vowels C(C) ___ • Genitive suffix – -[in] / front non-round vowels C(C) ___ – -[ün] / front round vowels C(C) ___ – -[ɨn] / back non-round vowels C(C) ___ – -[un] / back round vowels C(C) ___ Subscript and superscript convention • C1 = one or more consonants: C, CC, CCC, etc. • C0 = zero or more consonants: 0, C, CC, CCC, etc. • C1 = at most one consonant: 0, C 2 • C1 = minimum one, maximum 2 C: C(C) Analysis of alternating morphemes • Symmetrical distribution of suffix alternants • No non-alternating suffixes No single suffix alternant can be elevated to UR URs • UR = what all suffixes have in common • genitive: -/ V n/ [+high] (values of [back] and [round] will be added to match preceding vowel) an underspecified vowel, or ―archiphoneme‖ (Odden p. 239) Backness Harmony • Both high and non-high suffixes assimilate in backness to a preceding vowel • Backness Harmony: V --> [+ back] / V C0 ____ [+back] V --> [-back] / V C0 ____ [-back] (―collapsed‖) V --> [ back] / V C0 ____ [ back] (This is essentially the same as Hayes‘ [featurei].. -

Phonemic Vs. Derived Glides

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/240419751 Phonemic vs. derived glides ARTICLE in LINGUA · DECEMBER 2008 Impact Factor: 0.71 · DOI: 10.1016/j.lingua.2007.10.003 CITATIONS READS 14 32 1 AUTHOR: Susannah V Levi New York University 24 PUBLICATIONS 172 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Susannah V Levi Retrieved on: 09 October 2015 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Lingua 118 (2008) 1956–1978 www.elsevier.com/locate/lingua Phonemic vs. derived glides Susannah V. Levi * Department of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, New York University, 665 Broadway, 9th Floor, New York, NY 10003, United States Received 2 February 2007; received in revised form 30 June 2007; accepted 2 October 2007 Available online 27 September 2008 Abstract Previous accounts of glides have argued that all glides are derived from vowels. In this paper, we examine data from Karuk, Sundanese, and Pulaar which reveal the existence of two types of phonologically distinct glides both cross-linguistically and within a single language. ‘‘Phonemic’’ glides are distinct from underlying vowels and pattern with other sonorant consonants, while ‘‘derived’’ glides are non-syllabic, positional variants of underlying vowels and exhibit vowel-like behavior. It is argued that the phonological difference between these two types of glides lies in their different underlying featural representations. Derived glides are positional variants of vowels and therefore featurally identical. In contrast, phonemic glides are featurally distinct from underlying vowels and therefore pattern differently. Though a phono- logical distinction between these two types of glides is evident in these three languages, a reliable phonetic distinction does not appear to exist. -

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M. Hyman 5.1. Introduction The historical relation between African and general phonology has been a mutu- ally beneficial one: the languages of the African continent provide some of the most interesting and, at times, unusual phonological phenomena, which have con- tributed to the development of phonology in quite central ways. This has been made possible by the careful descriptive work that has been done on African lan- guages, by linguists and non-linguists, and by Africanists and non-Africanists who have peeked in from time to time. Except for the click consonants of the Khoisan languages (which spill over onto some neighboring Bantu languages that have “borrowed” them), the phonological phenomena found in African languages are usually duplicated elsewhere on the globe, though not always in as concen- trated a fashion. The vast majority of African languages are tonal, and many also have vowel harmony (especially vowel height harmony and advanced tongue root [ATR] harmony). Not surprisingly, then, African languages have figured dispro- portionately in theoretical treatments of these two phenomena. On the other hand, if there is a phonological property where African languages are underrepresented, it would have to be stress systems – which rarely, if ever, achieve the complexity found in other (mostly non-tonal) languages. However, it should be noted that the languages of Africa have contributed significantly to virtually every other aspect of general phonology, and that the various developments of phonological theory have in turn often greatly contributed to a better understanding of the phonologies of African languages. Given the considerable diversity of the properties found in different parts of the continent, as well as in different genetic groups or areas, it will not be possible to provide a complete account of the phonological phenomena typically found in African languages, overviews of which are available in such works as Creissels (1994) and Clements (2000). -

ELISION in ESAHIE Victoria Owusu Ansah Abstract One of the Syllable Structure Changes That Occur in Rapid Speech Because of Sounds Influencing Each Other Is Elision

Ghana Journal of Linguistics 9.2: 22-43 (2020) ________________________________________________________________________ http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/gjl.v9i2.2 ELISION IN ESAHIE Victoria Owusu Ansah Abstract One of the syllable structure changes that occur in rapid speech because of sounds influencing each other is elision. This paper provides an account of elision in Esahie, also known as Sehwi, a Kwa language spoken in the Western North region of Ghana. The paper discusses the processes involved in elision, and the context within which elision occurs in the language. The paper shows that sound segments, syllables and tones are affected by the elision process. It demonstrates that elision, though purely a phonological process, is influenced by morphological factors such as vowel juxtapositioning during compounding, and at word boundary. The evidence in this paper show that there is an interface between phonology and morphology when accounting for elision in Esahie. Data for this study were gathered from primary sources using ethnographic and stimuli methods. Keywords: Elision, Esahie, Sehwi, Tone, Deletion, Phonology 1.0 Introduction This paper provides an account of elision in Esahie, a Kwa language spoken in the Western North Region of Ghana1. It discusses the processes involved in elision in Esahie, and the context within which elision occurs in the language. The paper demonstrates that elision is employed in Esahie as a syllable structure repair mechanism. Elision is purely a phonological process but can sometimes be triggered by morphological factors. Indeed, the works of (Abakah 2004a, 2004b), Abdul-Rahman (2013), Abukari (2018), Becker and Gouskova (2016) writing on Akan, Dagbani and Russia respectively, confirm that elision 1 Speakers of Esahie in Ghana number about 580,000 and they live mostly in the Western North Region of the country (Ghana Statistical Service Report 2012, 2010 National Population Census). -

The Development of the English Vocalic System

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND GERMAN AND TRANSLATION AND INTERPRETATION STUDIES DEGREE IN ENGLISH STUDIES FINAL DEGREE PROJECT THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE VOCALIC SYSTEM OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE: from Proto-Germanic to Present-Day English Student: Nekane Ariz Uriz Responsible for tutoring: Reinhard Bruno Stempel Academic course: 2019/2020 1 Abstract This dissertation focuses in the evolution of the vocalic system of English: the aim of this work is to analyze and explain why and how vowels have developed from Old English to Present-Day English. To begin with, the changes in the Indo-European and Proto- Germanic languages are concisely described, and later the changes in Old, Middle, and Modern English are more deeply analyzed until reaching the Present-Day English vowel system. Through this process and comparing studies by different expert authors in the area of linguistics, an attempt will be made to illustrate as clearly as possible what the evolution of the vowels has been and how they have become what they are today. Another main goal of this work is to analyze the changes taking into account the articulatory properties of vowels; that is, to have a general idea of the physiology of the mouth and the movement of its articulators to realize how vowels are formed by humans, which include raising or lowering and advancing or retracting the body of the tongue, rounding or not rounding the lips, and producing the movements with tense or lax gestures. Besides, different kinds of sound change are also provided to clarify how the linguistic environment affects the vowels, that is, their previous and next sounds. -

Two Statistical Approaches to Finding Vowel Harmony

Two Statistical Approaches to Finding Vowel Harmony Adam C. Baker University of Chicago [email protected] July 27, 2009 Abstract The present study examines two methods for learning and modeling vowel harmony from text corpora. The first uses Expectation Maximization with Hidden Markov Mod- els to find the most probable HMM for a training corpus. The second uses pointwise Mutual Information between distant vowels in a Boltzmann distribution, along with the Minimal Description Length principle to find and model vowel harmony. Both methods correctly detect vowel harmony in Finnish and Turkish, and correctly recognize that English and Italian have no vowel harmony. HMMs easily model the transparent neu- tral vowels in Finnish vowel harmony, but have difficulty modeling secondary rounding harmony in Turkish. The Boltzmann model correctly captures secondary roundness harmony and the opacity of low vowels in roundness harmony in Turkish, but has more trouble capturing the transparency of neutral vowels in Finnish. 1 Introduction: Vowel Harmony and Unsupervised Learning The problem of child language acquisition has been a driving concern of modern theoret- ical linguistics since at least the 1950s. But traditional linguistic research has focused on constructing models like the Optimality Theory model of phonology (Prince and Smolensky, 2004). Learning models for those theories like the OT learning theory in Riggle (2004) are 1 sought later to explain how a child could learn a grammar. A lot of recent research in computational linguistics has turned this trend around. Break- throughs in artificial intelligence and speech processing in the '80s has lead many phonologists starting from models with well-known learning algorithms and using those models to extract phonological analyses from naturally occurring speech (for an overview and implications, see Seidenberg, 1997). -

Consonant Mutation and Reduplication in Blin Singulars and Plurals

Consonant Mutation and Reduplication in Blin Singulars and Plurals Paul D. Fallon Howard University 1. Introduction Blin1, a Central Cushitic (Agaw) language of Eritrea, displays a complex series of consonant mutations between plural and singular forms, with several unusual properties. This paper describes several such properties, focusing on consonant mutation (or apophony), especially in relation to reduplication, using Correspondence Theory (McCarthy and Prince 1995) within the overall framework of Optimality Theory, drawing on data based on both published sources (e.g. Lamberti and Tonelli 1997) and the author's fieldwork in Eritrea. This paper describes the rare interaction between mutation and reduplication, and provides additional support for Mc Laughlin's (2000) analysis of mutation as the result of featural affixation (Akinlabi 1996, Zoll 1998) to the root node of a consonant. However, unlike Mc Laughlin's analysis, where mutation was stem-initial, in Blin such mutation is stem-final. One of the more unusual properties of Blin is that for phonological purposes, it is often easier to take the plural as the underlying form, since singulars and singulatives are morphologically marked. For example, /kr/ 'stones' has a singular /kr-a/. One common mutation is the lenition of velar stops: /lk/ 'fires', /lx-a/ (sg.). The loss of continuancy also results in the loss of ejection (/ak'/ → /ax-a/ 'cave (pl./sg.)', but not labialization /kin/ → /xin-a/ 'woman (pl./sg.)', /sak’/ → /sax-a/ 'fat (n.)(pl./sg.)'. In addition, velar lenition may occur word-medially, e.g. [bkl] → [bxl-a] 'mule (pl./sg.)'. More than one mutation process may also occur within the word: /dk’l/ → /dxar-a/ 'donkey (pl./sg.)'. -

An Analysis of I-Umlaut in Old English

An Analysis of I-Umlaut in Old English Meizi Piao (Seoul National University) Meizi Piao. 2012. An Analysis of I-Umlaut in Old English. SNU Working Papers in English Linguistics and Language X, XX-XX Lass (1994) calls the period from Proto-Germanic to historical Old English ‘The Age of Harmony’. Among the harmony processes in this period, i-umlaut has been considered as ‘one of the most far-reaching and important sound changes’ (Hogg 1992, Lass 1994) or as ‘one of the least controversial sound changes’ (Colman 2005). This paper tries to analyze i-umlaut in Old English within the framework of the Autosegmental theory and the Optimality theory, and explain how suffix i or j in the unstressed syllable cause the stem vowels in the stressed syllable to be fronted or raised. (Seoul National University) Keywords: I-umlaut, Old English, Autosegmental theory, vowel harmony Optimality theory 1. Introduction Old English is an early form of the English language that was spoken and written by the Anglo-Saxons and their descendants in the area now known as England between at least the mid-5th century to the mid-12th century. It is a West Germanic language closely related to Old Frisian. During the period of Old English, one of the most important phonological processes is umlaut, which especially affects vowels, and become the reason for the superficially irregular and unrelated Modern English phenomenon. I-Umlaut is the conditioned sound change that the vowel either moves directly forward in the mouth [u>y, o>e, A>&] or forward and up [A>&>e]. -

From Dilation to Coarticulation: Is There Vowel Harmony in French? Zsuzsanna Fagyal, Noël Nguyen, Philippe Boula De Mareüil

From dilation to coarticulation: is there vowel harmony in French? Zsuzsanna Fagyal, Noël Nguyen, Philippe Boula de Mareüil To cite this version: Zsuzsanna Fagyal, Noël Nguyen, Philippe Boula de Mareüil. From dilation to coarticulation: is there vowel harmony in French?. Studies in the linguistic sciences, Urbana, Ill. : Department of Linguistics, University of Illinois, 2003, 32 (2), pp.1-21. hal-00308395 HAL Id: hal-00308395 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00308395 Submitted on 30 Jul 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences Volume 32, Number 2 (Spring 2002) FROM DILATION TO COARTICULATION: IS THERE VOWEL HARMONY IN FRENCH ? Zsuzsanna Fagyal*, Noël Nguyen#, and Philippe Boula de Mareüil± *University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign # Laboratoire Parole et Langage, CNRS & Université de Provence, Aix-en- Provence, France ± LIMSI, CNRS, Orsay [email protected] This paper presents the preliminary results of an acoustic study, and a review of previous work on vowel harmony in French. It shows that harmony, initially regarded as regular sound change, is considered an optional constraint on the distribution of mid vowels. Acoustic evidence of anticipatory assimilation of pretonic mid vowels to tonic high and low vowels is shown in three speakers' readings of disyllabic words in two dialects. -

How to Study a Tone Language, with Exemplification from Oku (Grassfields Bantu, Cameroon)

UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2010) How To Study a Tone Language, with exemplification from Oku (Grassfields Bantu, Cameroon) Larry M. Hyman University of California, Berkeley DRAFT • August 2010 • Comments Welcome 1. Introduction On numerous occasions I have been asked, “How does one study a tone language?” Or: “How can I tell if my language is tonal?” Even seasoned field researchers, upon confronting their first tone system, have asked me: “How do I figure out the number of tones I have?” When it comes to tone, colleagues and students alike often forget everything they’ve learned about discovering the phonology of a language and assume that tone is somehow different, that it requires different techniques or expertise. Some of this may derive from an incomplete understanding of what it means to be a tone system. Prior knowledge of possible tonal inventories, tone rules, and tone- grammar interfaces would definitely be helpful to a field researcher who has to decipher a tone system. However, despite such recurrent encounters, general works on tone seem not to answer these questions—specifically, they rarely tell you how to start and how to discover. I sometimes respond to the last question, “How do I figure out the number of tones I have?”, by asking in return, “Well, how would you figure out the number of vowels you have?” Hopefully the answer would be something like: “I would get a word list, starting with nouns, listen carefully, transcribe as much detail as I can, and then organize the materials to see if I have been consistent.” (I will put off until §5 commentary concerning the use of speech software as an aid in linguistic discovery.) Although I don’t think the elicitation techniques that one applies in studying segmental vs.