Experience and Personal Narrative of Uncle Tom Jones; Who Was for Forty Years a Slave

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 85 ALARM SYSTEMS

§ 85-1 ALARM SYSTEMS § 85-2 Chapter 85 ALARM SYSTEMS § 85-1. Short title. § 85-2. Definitions. § 85-3. Registration of system required. § 85-4. Timing mechanisms. § 85-5. Remote-controlled fences and gates. § 85-6. False alarm fees. § 85-7. Effect of chapter on pending proceedings. § 85-8. Compliance required. § 85-9. Violations and penalties. [HISTORY: Adopted by the Borough Council of the Borough of North Wales 12-22-1992 as Ord. No. 653. Amendments noted where applicable.] GENERAL REFERENCES Fire Department — See Ch. 21. Police Department — See Ch. 55. Fire prevention — See Ch. 118. § 85-1. Short title. This chapter shall be known as the "Alarm Systems Ordinance of North Wales." § 85-2. Definitions. As used in this chapter, the following terms shall have the meanings indicated: 8501 § 85-2 NORTH WALES CODE § 85-2 ALARM EQUIPMENT SUPPLIER — Any person who sells, leases and/or installs automatic protection devices or audible alarm systems. ALARM USER Any person in control of a premises having an audible alarm system or automatic protection device which notifies the Police Department or Fire De- partment, either directly or indirectly, and requires the response of the Police Department or Fire Department or a rescue company. ANSWERING SERVICE — A service whereby trained employees who are in attendance at all times receive prerecorded messages or signals from automatic protection devices reporting an emergency at a stated location, which employees have the duty to reply immediately, by live voice, any such emergency to the Police Department or Fire Department or rescue company. AUDIBLE ALARM — Any device, bell, horn or siren which is attached to the interior or exterior of a building, which emits a warning signal audible outside the building and which is designed to attract attention when activated by a criminal act or emergency requiring police, firefighters or a rescue company to respond. -

Fire and Burglary System

FFiirree aanndd BBuurrggllaarryy SSyysstteemm User's Manual 5120XM N8031 6/96 TABLE OF CONTENTS SYSTEM OVERVIEW...................................................................................... 3BYPASSING BURGLARY PROTECTION ZONES ................................... 18 General.......................................................................................................... 3Using the BYPASS Key ............................................................................. 18 Zones............................................................................................................. 3Quick Bypass .............................................................................................19 Fire & Emergency Protection ......................................................................3ARMING PERIMETER BURGLARY PROTECTION ONLY (STAY) ...... 20 Burglary Protection....................................................................................... 4ARMING PERIMETER BURG. PROTECTION ONLY (INSTANT) ........ 21 Alarms........................................................................................................... 4 ARMING ALL BURGLARY PROTECTION (AWAY)................................. 22 Memory of Alarm .........................................................................................4 ARMING ALL BURGLARY PROTECTION (MAXIMUM)......................... 23 ABOUT THE KEYPADS ..................................................................................5 General......................................................................................................... -

AMP2-16V Series User Guide

AMP2-16V Series • AMP2-16V-M • AMP2-E16V-M Modular Audio/Video Management and Monitoring Platform User Guide (Software Release: V7.xx) Part Number 821116, Revision M © 2017 Wohler Technologies, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by federal copyright law. No part of this publication may be copied or distributed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any human or computer language in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, manual, magnetic, or otherwise, or disclosed to third parties without the express written permission of Wohler Technologies. Reproduction Licensed users and authorized distributors of Wohler Technologies, Inc. products may copy this document for use with Wohler Technologies., Inc. products provided that the copyright notice above is included in all reproductions. Customer Support Wohler Technologies, Inc. 31055 Huntwood Avenue Hayward, CA 94544 www.wohler.com Phone: 510-870-0810 FAX: 510-870-0811 US Toll Free: 1-888-596-4537 (1-888-5-WOHLER) Web: www.wohler.com Sales: [email protected] Support: [email protected] Disclaimers Even though Wohler Technologies, Inc. has tested its equipment and software, and reviewed the documentation, Wohler Technologies, Inc makes no warranty or representation, either express or implied, with respect to software, documentation, their quality, performance, merchantability, or fitness for a particular purpose. In no event will Wohler Technologies, Inc. be liable for direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages resulting from any defect in the hardware, software, or its documentation, even if advised of the possibility of such damages. Some states do not allow the exclusion or limitation for incidental or consequential damages, so the above exclusion or limitation may not apply to you. -

Business Fire Safety Log Book

Business Fire Safety Log Book It is best practice to keep this log book up to date as it may be inspected by the Fire and Rescue Authority. Property/Business Name Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Town Post Code Contact Name 1 Contact Name 2 Gwasanaeth Tân ac Achub Fire and Rescue Service Gwasanaeth Tân ac Achub Fire and Rescue Service Contents Useful Contacts Page 3 The Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 Page 4 General Fire Safety Requirements Page 6 Fire Alarm System Page 8 Unwanted Fire Signals Page 10 Emergency Lighting System Page 12 Fire Fighting Equipment Page 14 Sprinkler Systems Page 16 Smoke Ventilation Systems Page 18 Miscellaneous Provisions Page 19 Fire Instruction and Training Page 21 Fire Evacuation and Drills Page 23 Fire Risk Assessment Page 25 Business Continuity and Planning Page 26 Useful Telephone Contacts Contact Company Number Fire Alarm Service Engineer Fire Extinguisher Engineer Emergency Lighting Engineer Sprinkler Engineer For further fire safety advice please contact: ADVICE LINE: 01443 232000 email [email protected] Information about Fire Protection or other related matters can be found on the South Wales Fire and Rescue Service website www.southwales-fire.gov.uk and www.fire.gov.uk Information and guidance is available in the fire safety guides published by Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government www.communities.gov.uk The Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 The vast majority of sites and business premises throughout England and Wales must now conform with the requirements of the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 (the “Fire Safety Order”), which has replaced the Fire Precautions Act 1971 and the Fire Precautions (Workplace) Regulations 1997, as well as over 100 pieces of legislation relating to Fire Safety. -

Dj Vladi Playlist Christmas Songs 2014

DJ VLADI PLAYLIST CHRISTMAS SONGS 2014 Dean Martin - Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Judith Durham - White Christmas Al Martino - Silver Bells Jo Stafford - Winter Wonderland Bing Crosby - Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas Vera Lynn - Away In A Manger Wayne Newton - Hark! The Herald Angels Sing Ella Fitzgerald - God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen John Farnham - The First Noel Anne Murray - It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Dion - Rockin' Around The Christmas Tree Crystal Gayle - I'll Be Home For Christmas Jan & Dean - Frosty The Snowman Les Paul - Jingle Bells The Spinners - The Twelve Days Of Christmas Lou Rawls - Merry Christmas, Baby Carnie & Wendy Wilson - Jingle Bell Rock Ferrante & Teicher - Sleigh Ride Stacie Orrico - O Come, All Ye Faithful Matt Monro - Mary's Boy Chi ld Eternal - Amazing Grace Kenny Rogers - When A Child Is Born Jamelia - Last Christmas Celtic Woman - O Holy Night Sin ad O'Connor - Silent Night Aled Jones - Walking In The Air Shirley Bassey - Ave Maria {Disc 2} Cliff Richard - Mistletoe And Wine Sarah Brightman - I Believe In Father Christmas the bird and the bee - Carol Of The Bells Amy Grant - Grown-Up Christmas List Glen Campbell - Blue Christmas Deniece Williams - Do You Hear What I Hear? Willie Nelson feat. Norah Jones - Baby It's Cold Outside Bobby Goldsboro - Look Around You Andy Williams - Christmas Holiday Barry Blue - Christmas Moon 11.Keith Marshall - Another Christmas Aaron Neville - Christmas Prayer Dianne Reeves - Christmas Time Is Here Bebe & Cece Winans - Joy To The World Faith Evans -

Platinum Plus and Platinum Junior Controllers

Platinum Plus and Platinum Junior Controllers User Manual (Precision) P/N: 110016 WARRANTY & LIMITATION OF LIABILITY 1. ROTEM warrants that the product shall be free of defects in materials or workmanship and will conform to the technical specification for a period of 1 (one) year from the date of initial installation on site (the "warranty period"). 2. Load cells are not covered by ROTEM’s warranty. 3. ROTEM warrants that during said warranty period, any item/items or part/parts of equipment found defective with respect to materials or workmanship or which do not conform to the technical specification shall be repaired or replaced (at ROTEM's sole discretion), free of charge. 4. During the warranty period, in the event of an alleged defect, authorized resellers in relevant regions should be notified as soon as possible from the date of noticing the said defect, but no longer than thirty (30) days from such a discovery. The report shall include (1) a short description of the defects noticed (2) type of card / component and its matching serial number. 5. ROTEM's sole liability under this warranty is the repair or replacement of the defective item of product. CONDITIONS AND LIMITATIONS 1. ROTEM will not be responsible for any labor costs or expenses associated with replacement of defective items or other parts of the product or repair. 2. This warranty shall not cover: (i) product or part therein which has been modified (without prior written approval of ROTEM), or (ii) product or part therein which has not handled or installed by an authorized reseller of ROTEM or (iii) product or part therein which has either handled or installed not in strict accordance with ROTEM's instructions, (iv) products which were used for function other than agriculture industry. -

Bach Flower Remedies & Mixes

BACH FLOWER REMEDIES & MIXES Agrimony "The jovial, cheerful, humorous people who love peace and are distressed by argument or quarrel, to avoid which they will agree to give up much. Though generally they have troubles and are tormented and restless and worried in mind or in body, they hide their cares behind their humor and jesting and are considered very good friends to know. They often take alcohol or drugs in excess, to stimulate them and help themselves bear their trials with cheerfulness." - Dr. Edward Bach Aspen "Vague unknown fears, for which there can be given no explanation, no reason. It is a terror that something awful is going to happen even though it is unclear what exactly. These vague inexplicable fears may haunt by night or day. Sufferers may often be afraid to tell their trouble to others." - Dr. Edward Bach Beech "For those who feel the need to see more good and beauty in all that surrounds them. And, although much appears to be wrong, to have the ability to see the good growing within. So as to be able to be more tolerant, lenient and understanding of the different way each individual and all things are working to their own perfection." - Dr. Edward Bach Centaury "Kind, quiet, gentle people who are over-anxious to serve others. They overtax their strength in their endeavors. Their wish so grows upon them that they become more servants than willing helpers. Their good nature leads them to do more than their own share of work, and in so doing they may neglect their own particular mission in life" - Dr. -

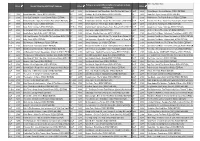

Price Record Store Day 2021 Drop1 Releases Price Follow Us on Twitter @Piccadillyrecs for Updates on Items Selling out E

Fill In Your Name Here: Follow us on twitter @PiccadillyRecs for updates on items Price ✓ Record Store Day 2021 Drop1 Releases Price ✓ Price ✓ selling out etc. LP's 2xLP 36.99 Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds : Back The Way We Came: Vol 12xLP (2011-2021)24.99 - ColouredRoisin Double Murphy LP : HandCrooked Pressed Machine With (RSD21 Exclusive EDITION) Art Print (RSD21 EDITION) LP 25.99 Kamal Abdul-Alim : Dance (RSD21 EDITION) LP 24.99 Garbage : No Gods No Masters (RSD21 EDITION) LP 24.99 Nada Surf : Cycle Through (RSD21 EDITION) LP 21.99 Asian Dub Foundation : Access Denied (RSD21 EDITION) LP 19.99 Howe Gelb : Hisser (RSD21 EDITION) LP 21.99 Molly Nilsson : The Travels Reissue (RSD21 EDITION) LP 28.99 Banda Black Rio : Super Nova Samba Funk (RSD21 EDITION) LP 25.99 Freddie Gibbs & Madlib : Pinata: The 1984 Version (RSD21 EDITION) 2xLP 40.99 The Notorious B.I.G. : Duets: The Final Chapter (RSD21 EDITION) LP 19.99 Bardo Pond : Volume 1 (RSD21 EDITION) LP 17.99 Girls In Synthesis : Shift In State (RSD21 EDITION) 2xLP 24.99 Conor Oberst : Ruminations (RSD21 EDITION) LP 19.99 Bardo Pond : Volume 2 (RSD21 EDITION) LP Box 97.99 Grateful Dead : Olympia Theatre, Paris, France 5/3/72 (RSD21 EDITION) 2xLP 22.99 Ocean Colour Scene : Saturday (RSD21 EDITION) 2xLP 25.99 BC Camplight : Hide, Run Away / Blink Of A Nihilist (RSD21 EDITION) LP 16.99 Owen Gray : Sings (RSD21 EDITION) 2xLP 39.99 Oh Sees : Live At The Chapel SF (RSD21 EDITION) LP 25.99 Beastie Boys : Aglio E Olio (RSD21 EDITION) LP 20.99 Al Green : Give Me More Love (RSD21 EDITION) LP -

Security System

SSeeccuurriittyy SSyysstteemm User's Manual VISTA-50P VISTA-50PUL N5943-6 7/95 TABLE OF CONTENTS SYSTEM OVERVIEW .................................... 3BYPASSING PROTECTION ZONES................ 22 A Partitioned System ................................ 3Quick Bypass ........................................23 Zones .................................................... 3Displaying Bypassed Protection Zones .......23 Fire Protection......................................... 4ARMING PERIMETER ONLY (STAY)........... 24 Burglary Protection .................................. 4ARMING PERIMETER ONLY (INSTANT) ..........25 Alarms ................................................... 4ARMING ALL PROTECTION (AWAY)............... 26 Memory of Alarm ...................................... 4ARMING ALL PROTECTION (MAXIMUM) .........27 Speed Key (Macros) ................................. 5DISARMING AND SILENCING ALARMS........... 28 Using Schedules...................................... 5USING THE KEYSWITCH.............................. 29 Device Timers ......................................... 5CHIME MODE............................................. 30 Accessing other partitions (GOTO command) 5 VIEWING CENTRAL STATION MESSAGES...... 31 Master Keypad Operation .......................... 6 PANIC KEYS.............................................. 32 Self-Help Feature ..................................... 6 Phone Access & Voice Response ............... 6SPEED KEY (MACROS) ...............................33 ABOUT THE KEYPADS.................................. 7ACCESS -

'Making a List, Checking It Twice' Tree Damaged at Old Roy's Site

•!• Greater Newark's Hometown Newspaper Since 1910 •!• 90th Year, Issue 44 © 1999 lTecember 1 0, 1999 Newark, Del. • 50¢ THis WEEK Tree ... damaged ..... --· IN .SPORTS at old Sr. MARK's, Roy's site CHRISTIANA Unauthorized HOOPS excavation cut into PREPFOR 21 roots of the tree SEASON. - By MARY E. PETZAK NEWARK POST STAFF WR ITER he sycamore tree on the former Roy Rogers site, currently under T development by NewCap on Main Street, may have been irreparably CEMETERY damaged during construction of a Charcoal Pit restaurant. "I walked by and looked at it," said GETIING Steven Dente!, chair of the Newark Conservation Advisory Commission. "Two significant roots on the tree are AFACE cut right through." According to city manager Carl Luft, LIFf he had the city staff examine the tree several weeks ago at the request of city councilmember Gerald Grant (District 6). "We thought the tree already was IN THE NEWS stressed by the construCtion," said Luft. "We analyzed the status at that time and made four recommendations to the con struction manager, including cabling the .CITY OF NEWARK . limbs of the tree, deep root feeding, and dead wooding and thinning the tree limbs." Will BURY However, before anything could be done, the city discovered the construc tion crews had proceeded to dig a trench TIME on the site which cut directly into the tree roots. "We're very upset about what they did- there's not even supposed to INA be a trench there, according to the sub CAPSULE. division plan," said Luft. "If they need- See TREE, 4 ~ INDEX WE ARE THE CHAMPIONS NEWS 1=5 ~- 'Making a list, POLICE BLOTTER 2 OPINION 8 checking it twice' LIFESTYLE 10 By SHARON COLE THE ARTS 11 . -

The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-Of-Age Narratives in Album Form

The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-of-Age Narratives in Album Form Dallas Killeen TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 2019 __________________________________________ Hannah Wojciehowski Department of English Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Chad Bennett Department of English Second Reader Abstract Author: Dallas Killeen Title: The Sonic Bildungsroman: Coming-of-Age Narratives in Album Form Supervising Professors: Hannah Wojciehowski, Ph.D. Chad Bennett, Ph.D. The Bildungsroman, or coming-of-age story, deals with the transitional period of adolescence. Although initially conceived in the novel form, the Bildungsroman has since found expression in various media. This thesis expands the scope of the genre by describing the “sonic Bildungsroman,” or coming-of-age album, and exploring a few key examples of this previously undefined concept. Furthermore, the record as a medium affords musicians narrative agency critical to their identity development, so this project positions the coming- of-age album squarely in the tradition of the Bildungsroman as a tool for self-cultivation. This thesis examines two albums in great detail: Pure Heroine by Lorde and Channel Orange by Frank Ocean. In these records, Lorde and Ocean lyrically, musically, and visually portray their journeys toward self-actualization. While the works show thematic similarities in their respective presentations of the adolescent experience, Lorde and Ocean craft stories colored by their unique identities. In this way, the two albums capture distinct approaches to constructing coming-of-age narratives in album form, yet both represent foundational examples of the genre due to their subject matter, narrative trajectory, and careful composition. From this basis, this project offers a framework for understanding how popular musicians construct coming-of-age stories in their albums—and for understanding how these stories affect us as listeners. -

THE ALARM 'STRENGTH (30Th ANNIVERSARY)'

THE ALARM ‘STRENGTH (30th ANNIVERSARY)’ Release date: 2nd October 2015 Record Label: The Twenty First Century Recording Company Formats: CD, Vinyl and Download Catalogue number: 21C074 MIKE PETERS TO RELEASE 30TH ANNIVERSARY REWORKING OF THE ALARM’S 1985 ALBUM ‘STRENGTH’ ‘If a man can't change the world these days, I still believe a man can change his own destiny". The Alarm - Strength (30th Anniversary) To mark the 30th anniversary of The Alarm’s highly acclaimed second album Strength, the entire album has been rearranged and rerecorded by the band’s lead singer and songwriter Mike Peters to create to create a brand new listening experience entitled ‘Strength (30th Anniversary)’. “I always felt that song for song, word for word, 'Strength' was The Alarm's best album of the 1980's and had layers of hidden qualities that were never truly revealed or properly explored back in those heady days", says Peters. Following last year’s release of the 30th anniversary edition of The Alarm’s debut album Declaration, the reworked songs on Strength (30th Anniversary) have shed their skin to live again for new times as the result of experience gained. "There are a lot of stories on Strength, many of them autobiographical or written from personal experience," continues Peters, "I still see the people I wrote about in the songs and live on the same streets affected by the political landscape documented in the original telling and I felt that they deserved an updating so that they could tell of challenges met and of relationships strengthened by time." To conceive the album for 2015, Mike Peters was aided by the original production notes and lyric book he had first started writing in as far back as 1984 when the band went to New York to work with uber-producer Jimmy Iovine (Credits include John Lennon, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Petty, U2, Patti Smith etc.).