Download Extinctions [PDF, 4.5MB]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

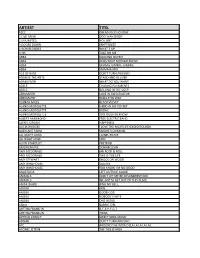

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

Hothouse Flowers

MTM Checks Out Europe's Own MTV Unplugged. Also, GrooveMix Looks At French Club Charts. See page 10 & 12. Europe's Music Radio Newsweekly Volume 10 . Issue 11 . March 13, 1993 . £ 3, US$ 5, ECU 4 Radio Wins UK PolyGram Operating Copyright Battle Income Up 7% broadcasting revenue, including by Thom Duffy & income from sponsorship, barter Mike McGeever and contra deals for the first time, by Steve Wonsiewicz Record companies inthe UK as well as advertising revenue. Worldwide music and entertain- have been dealt a major setback The ratefor stations with net ment group PolyGram reported in their bid to boost the royalty broadcastingrevenuebetween a 7.3% increaseinoperating payments they receive from com- US$1.02 million and US$525.000 income to Dfl 789 million (app. mercial radio stations, under a will drop to 3% and 2% for those US$448 million) on a 4.6% rise ruling handed down March 2 by with net income below in sales to Dfl 6.62 billion last the Copyright Tribunal. US$525.000. The royaltiesare year, despite a severe recession DANISH GRAMMIES - Danish band Gangway (BMG/Genlyd Den- In an action brought by the retroactive to April 1, 1991. in several of its key European mark) received four prizes in this year's Danish Grammy Show while Association ofIndependent The total operating profit of markets. Lisa Nilsson (Diesel Music, Sweden) took two awards. Pictured (4) are: Radio Contractors (AIRC) to set the commercial UK radio indus- Net income for thefiscal Tonja Pedersen (musician, Lisa Nilsson), Lasse Illinton (Gangway), BMG new broadcast royalty rates for 79 try in 1990-91 was approximately year ended December 31 was up label manager Susanne Kier, Diesel Music MD Torbjorn Sten, Lisa Nils- commercialradiocompanies, US$11 millionwithCapital 13.5% to Dfl 506 million. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Arry Music from the 40’S to All of Today’S Hits ! John E Martell Wedding Mobile Disc Jockeys 460 E

We carry music from the 40’s to all of today’s hits ! John E Martell Wedding Mobile Disc Jockeys 460 E. Lincoln Hwy. Specialists 215-752-7990 Langhorne Pa 19047 1/1/2017 SOME OF THE MUSIC AVAILABLE ( OUR MUSIC LIBRARY CONSISTS OF OVER 70,000 TITLES ) your name : ______________________ date of affair : ________________ location of affair : ___________________ [ popular dance ] ELECTRIC SLIDE - Marcia Griffiths CHA CHA SLIDE - DJ DON'T STOP BELIEVING - Journey OLD TIME ROCK N ROLL - Bob Seger WE ARE FAMILY - Sister Sledge DA BUTT - E U SO MANY MEN - Miguel Brown THIS IS HOW WE PARTY - S.O.A.P DO YOU WANNA FUNK - Sylvester FUNKYTOWN - Lipps Inc FEELS LIKE I'M IN LOVE - Kelly Marie THE BIRD - The Time IT'S RAINING MEN - Weather Girls SUPERFREAK-Rick James YOU DROPPED A BOMB-Gap Band BELIEVE - Cher ZOOT ZOOT RIOT-Cherry Poppin' Daddies IT TAKES TWO- Rob Base LOVE SHACK- B-52's EVERYBODY EVERYBODY-Black Box MIAMI- Will Smith HOT HOT HOT- Buster Poindexter HOLIDAY-Madonna JOCK JAMS- Various Artists IT WASN'T ME - Shaggy MACARENA- Los Del Rios RHYTHM IS A DANCER- Snap WHOOP THERE IT IS- Tag Team DO YOU REALLY WANT ME- Robyn GONNA MAKE YOU SWEAT- C&C Music TWLIGHT ZONE - 2 Unlimited PUMP UP THE JAM - Technotronics NEW ELECTRIC SLIDE - Grand Master Slice RAPPER'S DELIGHT - Sugar Hill Gang MOVE THIS - Technotronics HEARTBREAKER - Mariah Carey HIT MAN - A B Logic I'M GONNA GET YOU - Bizarre Inc SUPERMODEL - Ru Paul APACHE - Sugar Hill Gang CRAZY IN LOVE - Beyonce' DA DA DA - Trio GET READY FOR THIS - 2 Unlimited THE BOMB - Bucketheads STRIKE IT UP -

Grand Entrances Speciality Dances

Bat Mitzah Grand Entrances 1. Isn’t She Lovely – Stevie Wonder 14. Perfect Day ‐ Hoku 2. I’m Every Women – Whiteny Houston 15. I’m A Star ‐ Prince 3. Everything She Does Is Magic – Police 16. Pretty Women – Roy Orbison 4. Just Dance – Lady GaGa & Colby O’Donis 17. Waiting for Tonight – Jennifer Lopez 5. Glamorous – Fergie 18. Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison 6. Single Ladies – Beyonce 19. What Dreams Are Made Of – Hillary Duff 7. I’m Coming Out – Diana Ross 20. Get the Party Started ‐ Pink 8. Dancing Queen – Abba 21. Let’s Get It Started – Black Eyed Peas 9. She’s A Lady – Tom Jones 22. That Lady – Isley Brothers 10. Simply Irresistible – Robert Palmer 23. Don’t Ya – Pussycat Dolls 11. Beautiful Day – U2 24. Material Girl – Madonna 12. Forever – Chris Brown 25. One – Chrous Line 13. Beautiful – Akon 26. Beautiful – Snoop Dogg & Pharell Bar Mitzvah Grand Entrances 1. Macho Man – Village People 12. Yeah ‐ Usher 2. Wild Thing – Troggs/ Ton Loc 13. All Star ‐ Smashmouth 3. Let’s Hear It For the Boys – Denise Williams 14. Sharp Dressed Man – ZZ Tops 4. Pretty Fly (for a White Guy) – The Offspring 15. Party Like a Rock Star – Shop Boyz 5. #1 – Nelly 16. Fly Eagles Fly – Theme Song 6. We Fly High – Jim Jones 17. Chicago Bulls Theme – Theme Song 7. I’m Too Sexy – Right Said Fred 18. Born to Be Wild – Steppinwolf 8. Let’s Get It Started – Black Eyed Peas 19. World’s Greatest – R. Kelly 9. Mr. Big Stuff – Jean Knight 20. -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

SWR1 Hitwoch: Nummer 1-Hits Mittwoch, 28. September 2016 Title Artist

SWR1 Hitwoch: Nummer 1-Hits Mittwoch, 28. September 2016 Title Artist (I'll never be) Maria Magdalena Sandra 99 Luftballons Nena Absolute beginners David Bowie Ain't no doubt Jimmy Nail All about that bass Meghan Trainor All around the world Lisa Stansfield All of me John Legend American pie - part I Don McLean Angel Shaggy Annie's song John Denver Another day in paradise Phil Collins Auf uns Andreas Bourani Avenir Luane Babe Styx Baby come back Player Back for good Take That Bad Day Daniel Powter Bad moon rising Creedence Clearwater Revival Baila (Sexy thing) Zucchero Best of my love The Emotions Bette Davis eyes Kim Carnes Big girls don't cry Fergie Bonfire heart James Blunt Born to make you happy Britney Spears Brass in pocket Pretenders Breakfast at Tiffany's Deep Blue Something Bridge over troubled water Simon & Garfunkel Bright eyes Art Garfunkel Brown sugar The Rolling Stones Call me Blondie Can't get you out of my head Kylie Minogue Can't stop the feeling! Justin Timberlake Car wash Rose Royce Cat's in the cradle Harry Chapin Crazy little thing called love Queen Da ya think I'm sexy Rod Stewart Dancing in the city Marshall-Hain Dancing in the street David Bowie & Mick Jagger Dancing queen Abba Deeply dippy Right Said Fred Der Kommissar Falco Didn't we almost have it all Whitney Houston Do that to me one more time Captain & Tennille Don't be so shy Imany Don't gimme that The BossHoss Don't leave me this way Thelma Houston Don't stand so close to me The Police Don't wanna lose you Gloria Estefan Don't worry, be happy Bobby McFerrin Dreams Fleetwood Mac El condor pasa Simon & Garfunkel Ella, elle l'a France Gall Emotions Mariah Carey Everybody wants to rule the worldTears For Fears Everything I do ( I do it for you ) Bryan Adams Eye of the tiger Survivor Fairground Simply Red Fame Irene Cara Fastlove George Michael Fight for this love Cheryl Cole Fotoromanza Gianna Nannini Get lucky Daft Punk featuring Pharrell.. -

The Sunrise Jones Song List C/O Cleveland Music Group

The Sunrise Jones Song List c/o Cleveland Music Group Take on Me ‐ A‐ha Dancing Queen ‐ ABBA Shook Me All Night Long ‐ AC/DC Sweet Emotion ‐ Aerosmith Melissa ‐ Allman Brothers The Criminal ‐ Apple, Fionna What a Wonderful World ‐ Armstrong, Louis Love Shack ‐ B‐52's, The Walk Like an Egyptian ‐ Bangles, The Beatles Abbey Road Medley – You Never Give Me Your Money Abbey Road Medley – Sun King Abbey Road Medley – Mean Mr. Mustard Abbey Road Medley – Polythene Pam Abbey Road Medley – She Came In Through The Bathroom Window Abbey Road Medley – Golden Slumbers Abbey Road Medley – Carry That Weight Abbey Road Medley – The End Blackbird ‐ Beatles, The Birthday ‐ Beatles, The Don't Let Me Down ‐ Beatles, The Hey Jude ‐ Beatles, The I Saw Her Standing There ‐ Beatles, The Two of Us ‐ Beatles, The Twist and Shout ‐ Beatles, The Where It's At ‐ Beck Stayin' Alive ‐ Bee Gees Livin' On a Prayer ‐ Bon Jovi Golden Years ‐ Bowie, David Boot Scootin' Boogie ‐ Brooks and Dunn Friends in Low Places ‐ Brooks, Garth Just What I Needed ‐ Cars, The Folsom Prison Blues ‐ Cash, Johnny Twist ‐ Checker, Chubby Le Freak ‐ Chic Wonderful Tonight ‐ Clapton, Eric Feelin' Alright ‐ Cocker, Joe Do You Love Me? ‐ Contours, The Pump It Up ‐ Costello, Elvis & the Attractions Green River ‐ Credence Clearwater Revival Just Like Heaven ‐ Cure, The Achy Breaky Heart ‐ Cyrus, Billy Ray Party in the U.S.A. ‐ Cyrus, Miley Get Lucky ‐ Daft Punk Shout ‐ Day, Otis Lady in Red ‐ De Burgh, Chris You Spin Me Round (Like a Record) ‐ Dead or Alive Groove Is in the Heart ‐ Deee‐Lite Sweet -

Accident Claims Two Lives on Campus

22/11/01 The University of Surrey Students’ Newspaper www.ussu.co.uk Issue no: 1020 FREE The World After Will you watch Barearts What’s On? the Queen’s 8 Page Ents Pullout September 11th Speech? p9 - 16 p5 p3 p6-8, 17-20 News in Brief BY REUBEN THOMPSON Accident Levis Thrash Tesco In Court In a landmark ruling on Tuesday, the European Court of Justice ruled that Tesco could not import brand Claims Two name goods from the United States and elsewhere and sell them at lower prices than the officially rec- ommended ones. The supermarket chain had been buying goods at Lives On wholesale prices abroad (i.e. not in the EU) and then selling them on at reduced prices, and undercutting the brands' own chains by up to forty per cent. A spokesperson for Campus Levi Strauss, who sued the compa- ny over the affair said that it was good news for the consumer as "it BY TRISTAN O’DWYER Emergency services and will help to guarantee choice and Editor University security were on the the availability of new and interest- scene within minutes but unfortu- ing products". You have to won- A car crash on the morning of nately nothing could be done to der… Friday 16th November has result- save the men’s lives. The men have ed in the deaths of two young men. been named by Surrey Police as Plane Spotters Arrested For The accident occurred at around Mark Herbert and David Davies, Boring Hobby 12:30 AM on the Campus perime- both 23 years of age. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

Station Reports

STATION REPORTS COOL FM/Belfast GWR FM/Bristol/Swindon RTL: WRTL/Paris RADIO XANADU/Munich REIF 105 NETWORK/Milan RADIO NOORD-HOLLAND/Haarlem Station reports include John Paul BallantineHead Of Music Andy Westgate Head Of Musk Georges Lang Benny Schnhr Head Of Music Angelo De Robertis - Head Of Prog Pieter 130110 Producer A List: A List: Lionel Richebourg Power Ploy: A List A List: SWUM all new additions to the AD John Lennon- instant Karma AD Geoffrey William. Summer A List: Christopher Cros. In The Blink AD Double You- We All AD Banda Blanca Fiesta 40 PRINCIPALES/Madrid Suzanne Vegas Liverpool Link & Bikini KISSING AD Beach Boys Ho Fu^ Crowded House Weather Promised Land C,rcle Cover Girl. Wishing On Luis Merino - Music Mgr playlist,indicatedby B List: B List AL Dr. John Del Amitri. Alwoys Del Amilri- Be My Downfall Power Play: AD Beagle- The Things AD Beagle T. Things Thomas Dolby Jeremy Day. Loved RTL 102.5 - HIT RADIO/Bergamo Elton John, Runaway Train the abbreviation "AD." Tramp* Al Ledo De Ti Cygnet Ring- Banjos In Cud Purple Love Mr. Big Just Toke My Grant Benson - Head Of Musk En Vogue Giving Him Double lox We All Daryl Braithwaite Horses ISABELLE FM/Tocane Saint Apre Stefan Andersson- Ws Over A List: Jimmy Nail- Ain't No Doubt A List: Reports fromcertain AD Bobby Brown Hun.' Esperanto- Love Is Lionel Richie- My Destiny Patrick Lopeyronnie Prog Dir AD Roxette How Do AD Betty Boo Let Me Lionel Richie My Destiny Cellos Corto. Ya Ester stations will also Lionel Richie My Destiny Shamen.