Final Report '01 Focus Areaswildlife Habitat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lost Lake/ Knops Pond Groton, MA Resource Management Plan

Lost Lake/ Knops Pond Groton, MA Resource Management Plan Dsa\ “A lake is the landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature.” Henry David Thoreau Prepared by: Groton Lakes Association Revision 4.01 August 12, 2012 Table of Contents Part 1- Overview, Identification and Inventories ................................................................ 3 Overview & Executive Summary ....................................................................................... 3 Lake Identification .............................................................................................................. 3 Inventory of Physical Conditions........................................................................................ 6 Species and Wildlife Habitat Inventory ............................................................................ 13 Inventory of Structures ..................................................................................................... 16 Human Use Activity Inventory ......................................................................................... 16 Part 2- Action Plan ............................................................................................................ 17 Goals and Objectives ........................................................................................................ 17 Weed Management .......................................................................................................... -

Botanical Survey of Bussey Brook Meadow Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts

Botanical Survey of Bussey Brook Meadow Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts Botanical Survey of Bussey Brook Meadow Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts New England Wildflower Society 180 Hemenway Road Framingham, MA 01701 508-877-7630 www.newfs.org Report by Joy VanDervort-Sneed, Atkinson Conservation Fellow and Ailene Kane, Plant Conservation Volunteer Coordinator Prepared for the Arboretum Park Conservancy Funded by the Arnold Arboretum Committee 2 Conducted 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................4 METHODS....................................................................................................................................6 RESULTS .......................................................................................................................................8 Plant Species ........................................................................................................................8 Natural Communities...........................................................................................................9 DISCUSSION .............................................................................................................................15 Recommendations for Management ..................................................................................15 Recommendations for Education and Interpretation .........................................................17 Acknowledgments..............................................................................................................19 -

Developing a Strategy Guide for Trail Planning in Princeton, Massachusetts

2020 DEVELOPING A STRATEGY GUIDE FOR TRAIL PLANNING IN PRINCETON, MASSACHUSETTS Matthew Karns Mason Ocasio Steven Pardo Mackenzie Warren Advisors John-Michael Davis 0 Hektor Kashuri Developing a Strategy Guide for Trail Planning in Princeton, Massachusetts An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by: Matthew Karns Mason Ocasio Steven Pardo Mackenzie Warren Date: May 13th, 2020 Report Submitted to: Rick Gardner Princeton Open Space Committee Professor John-Michael Davis Professor Hektor Kashuri Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate students submitted to the faculty as evidence of a degree requirement. WPI routinely publishes these reports on its web site without editorial or peer review. For more information about the projects program at WPI, see http://www.wpi.edu/Academics/Projects. ABSTRACT Princeton, Massachusetts, has faced challenges negotiating with private and government entities to develop a town-wide connected recreational trail system. This project provides a detailed strategy guide for the Princeton Open Space Committee to overcome these challenges and develop future trails in Princeton. To achieve this, we conducted a GIS analysis of existing trails, consulted with key stakeholders to determine trail building regulations, and interviewed 11 local trail planning groups to determine best practices for trail standards and maintenance plans. Based on our findings, we provided a comprehensive trail map and recommendations to advance future trail projects. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our group would like to thank the following people and organizations for supporting this project: ● The Princeton Open Space Committee, for an opportunity to complete this project. -

Tall Pines Trail

Tall Pines Trail Location: Mohawk Trail State Forest. Updated 7-29-2019 County: Franklin Township: Charlemont Start and End of Trail Network: Lat 42.638425 N, Long 72.936285 W Trail length (complete loop plus spur): 3.0 miles Introduction Mohawk Trail State Forest (MTSF) was one of the first state forests to be established as part of the Massachusetts system of Forests and Parks. Today the property covers approximately 6,700 acres and is split by State Route #2, named the Mohawk Trail in recognition of the ancient Indian path that ran from the waters of the Hudson to the Connecticut River. MTSF is mountainous, possessing some of the most rugged topography in the Commonwealth. The Cold River and Deerfield River gorges reach depths of 1,000 feet in Mohawk, and elevations vary from 600 to almost 2100 feet within the property. Mohawk has many outstanding features, including: (1) its wealth of old growth forests (nearly half of the total for Massachusetts), (2) record-breaking tall, second-growth white pines, (3) a section of the original Mohawk Indian Trail, (4) section of the old Shunpike, (5) site of an old Indian encampment, and (6) the gravesite of Revolutionary War veteran John and his wife Susannah Wheeler. The State Forest is part of the 9th Forest Reserve, which is maintained in pristine condition. The Park area is located on the north side of Route #2, and includes the Headquarters, picnic area, campground (for RVs and tents), cabin area (six rental cabins), the Old Cold River Road, and the upper and lower meadows. -

Continuous Forest Inventory 2014

Manual for Continuous Forest Inventory Field Procedures Bureau of Forestry Division of State Parks and Recreation February 2014 Massachusetts Department Conservation and Recreation Manual for Continuous Forest Inventory Field Procedures Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation February, 2014 Preface The purpose of this manual is to provide individuals involved in collecting continuous forest inventory data on land administered by the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation with clear instructions for carrying out their work. This manual was first published in 1959. It has undergone minor revisions in 1960, 1961, 1964 and 1979, and 2013. Major revisions were made in April, 1968, September, 1978 and March, 1998. This manual is a minor revision of the March, 1998 version and an update of the April 2010 printing. TABLE OF CONTENTS Plot Location and Establishment The Crew 3 Equipment 3 Location of Established Plots 4 The Field Book 4 New CFI Plot Location 4 Establishing a Starting Point 4 The Route 5 Traveling the Route to the Plot 5 Establishing the Plot Center 5 Establishing the Witness Trees 6 Monumentation 7 Establishing the Plot Perimeter 8 Tree Data General 11 Tree Number 11 Azimuth 12 Distance 12 Tree Species 12-13 Diameter Breast Height 13-15 Tree Status 16 Product 17 Sawlog Height 18 Sawlog Percent Soundness 18 Bole Height 19 Bole Percent Soundness 21 Management Potential 21 Sawlog Tree Grade 23 Hardwood Tree Grade 23 Eastern White Pine Tree Grade 24 Quality Determinant 25 Crown Class 26 Mechanical Loss -

List of Insect Species Which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists

Conservation Biology Research Grants Program Division of Ecological Services © Minnesota Department of Natural Resources List of Insect Species which May Be Tallgrass Prairie Specialists Final Report to the USFWS Cooperating Agencies July 1, 1996 Catherine Reed Entomology Department 219 Hodson Hall University of Minnesota St. Paul MN 55108 phone 612-624-3423 e-mail [email protected] This study was funded in part by a grant from the USFWS and Cooperating Agencies. Table of Contents Summary.................................................................................................. 2 Introduction...............................................................................................2 Methods.....................................................................................................3 Results.....................................................................................................4 Discussion and Evaluation................................................................................................26 Recommendations....................................................................................29 References..............................................................................................33 Summary Approximately 728 insect and allied species and subspecies were considered to be possible prairie specialists based on any of the following criteria: defined as prairie specialists by authorities; required prairie plant species or genera as their adult or larval food; were obligate predators, parasites -

Singletracks #41 December 1998

The Magazine of the New England Mountain Bike Association December 1998 Number 41 SSingleingleTTrackrackSS FlyingFlyingFlyingFlying HighHighHighHigh WithWithWithWith MerlinMerlinMerlinMerlin NEMBANEMBA goesgoes WWestest HotHot WinterWinter Tips!Tips! BlueBlue HillsHills MountainMountain FFestest OFF THE FRONT Howdy, Partner! artnerships are where it's at. Whether it's captain NEMBA is working closely with the equestrian group, and stoker tandemming through the forest, you the Bay State Trail Riders Association. Not only did the Pand your buds heading off to explore uncharted groups come together to ride and play a bit of poker to trails, or whether it's organizations like NEMBA teaming celebrate the new trails at Mt. Grace State Forest in up with other groups, partnerships make good things Warwick MA, but over the course of the summer they happen. also built new trail loops in Upton State Forest. Many of the misunderstandings between the horse and bike Much of this issue is about partnerships -- set were thrown out the window as they jockeyed for well, maybe not of the squeeze kind-- and position and shared the trails. There are already plans why they're good for New England trails. In for a second Hooves and Pedals, so if you missed the October, GB NEMBA's trail experts took first one, don't miss the next. leadership roles in an Appalachian Mountain Club project designed to assess NEMBA's been building many bridges over the last year, the trails of the Middlesex Fells both literally and figuratively. We're working closely Reservation. Armed with cameras and clip- with more land managers and parks than I can count boards, they led teams across the trails to and we've probably put in just as many bridges and determine the state of the dirt and to figure boardwalks! We’ve also secured $3000 of funding to out which ones needed some tender loving overhaul the map of the Lynn Woods working together care. -

Fishing Regulations, 2020-2021, Available Online, from Your License Distributor, Or Any DNR Service Center

Wisconsin Fishing.. it's fun and easy! To use this pamphlet, follow these 5 easy steps: Restrictions: Be familiar with What's New on page 4 and the License Requirements 1 and Statewide Fishing Restrictions on pages 8-11. Trout fishing: If you plan to fish for trout, please see the separate inland trout 2 regulations booklet, Guide to Wisconsin Trout Fishing Regulations, 2020-2021, available online, from your license distributor, or any DNR Service Center. Special regulations: Check for special regulations on the water you will be fishing 3 in the section entitled Special Regulations-Listed by County beginning on page 28. Great Lakes, Winnebago System Waters, and Boundary Waters: If you are 4 planning to fish on the Great Lakes, their tributaries, Winnebago System waters or waters bordering other states, check the appropriate tables on pages 64–76. Statewide rules: If the water you will be fishing is not found in theSpecial Regulations- 5 Listed by County and is not a Great Lake, Winnebago system, or boundary water, statewide rules apply. See the regulation table for General Inland Waters on pages 62–63 for seasons, length and bag limits, listed by species. ** This pamphlet is an interpretive summary of Wisconsin’s fishing laws and regulations. For complete fishing laws and regulations, including those that are implemented after the publica- tion of this pamphlet, consult the Wisconsin State Statutes Chapter 29 or the Administrative Code of the Department of Natural Resources. Consult the legislative website - http://docs. legis.wi.gov - for more information. For the most up-to-date version of this pamphlet, go to dnr.wi.gov search words, “fishing regulations. -

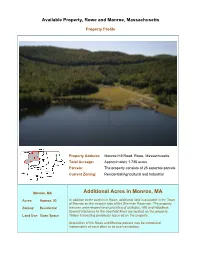

Additional Acres in Monroe, MA

Available Property, Rowe and Monroe, Massachusetts Property Profile Property Address: Monroe Hill Road, Rowe, Massachusetts Total Acreage: Approximately 1,735 acres Parcels: The property consists of 25 separate parcels Current Zoning: Residential/Agricultural and Industrial Monroe, MA Additional Acres in Monroe, MA Acres: Approx. 93 In addition to the parcels in Rowe, additional land is available in the Town of Monroe on the western side of the Sherman Reservoir. The property Zoning: Residential features undeveloped land consisting of plateaus, hills and ridgelines. Several tributaries to the Deerfield River are located on the property. Land Use: Open Space Timber harvesting previously occurred on the property. Acquisition of the Rowe and Monroe parcels may be completed independent of each other or as one transaction. Available Property, Rowe and Monroe, Massachusetts Property Location: The two properties are located in the Towns of Monroe and Rowe in the northwest corner of Franklin County, Massachusetts. The towns of Monroe and Rowe are separated by Sherman Reservoir, the largest lake on the Deerfield River. Franklin County is a sparsely populated rural area in north central Massachusetts. The land is currently owned by Yankee Atomic Electric Company. The decommissioned Yankee Rowe nuclear power station was previously located on approximately 80 acres of the property. The remaining land served as open space buffer land during the plant’s operation. Franklin County Massachusetts Rowe Property Description: The Rowe property is located in the northwest corner of the Town of Rowe at its border with the State of Vermont and east of the Sherman Reservoir. The property is accessed via Monroe Hill Road, a well- maintained secondary Town- owned roadway. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Mercury Pollution in Massachusetts' Waters

Photo: Supe87, Under license from Shutterstock.com from Supe87, Under license Photo: ToXIC WATERWAYS Mercury Pollution in Massachusetts’ Waters Lauren Randall Environment Massachusetts Research & Policy Center December 2011 Executive Summary Coal-fired power plants are the single larg- Human Services advises that all chil- est source of mercury pollution in the Unit- dren under twelve, pregnant women, ed States. Emissions from these plants even- women who may become pregnant, tually make their way into Massachusetts’ and nursing mothers not consume any waterways, contaminating fish and wildlife. fish from Massachusetts’ waterways. Many of Massachusetts’ waterways are un- der advisory because of mercury contami- Mercury pollution threatens public nation. Eating contaminated fish is the main health source of human exposure to mercury. • Eating contaminated fish is the main Mercury pollution poses enormous public source of human exposure to mercury. health threats. Mercury exposure during • Mercury is a potent neurotoxicant. In critical periods of brain development can the first two years of a child’s life, mer- contribute to irreversible deficits in verbal cury exposure can lead to irreversible skills, damage to attention and motor con- deficits in attention and motor control, trol, and reduced IQ. damage to verbal skills, and reduced IQ. • While adults are at lower risk of neu- In 2011, the U.S. Environmental Protection rological impairment than children, Agency (EPA) developed and proposed the evidence shows that a low-level dose first national standards limiting mercury and of mercury from fish consumption in other toxic air pollution from existing coal- adults can lead to defects similar to and oil-fired power plants. -

Outdoor Recreation Recreation Outdoor Massachusetts the Wildlife

Photos by MassWildlife by Photos Photo © Kindra Clineff massvacation.com mass.gov/massgrown Office of Fishing & Boating Access * = Access to coastal waters A = General Access: Boats and trailer parking B = Fisherman Access: Smaller boats and trailers C = Cartop Access: Small boats, canoes, kayaks D = River Access: Canoes and kayaks Other Massachusetts Outdoor Information Outdoor Massachusetts Other E = Sportfishing Pier: Barrier free fishing area F = Shorefishing Area: Onshore fishing access mass.gov/eea/agencies/dfg/fba/ Western Massachusetts boundaries and access points. mass.gov/dfw/pond-maps points. access and boundaries BOAT ACCESS SITE TOWN SITE ACCESS then head outdoors with your friends and family! and friends your with outdoors head then publicly accessible ponds providing approximate depths, depths, approximate providing ponds accessible publicly ID# TYPE Conservation & Recreation websites. Make a plan and and plan a Make websites. Recreation & Conservation Ashmere Lake Hinsdale 202 B Pond Maps – Suitable for printing, this is a list of maps to to maps of list a is this printing, for Suitable – Maps Pond Benedict Pond Monterey 15 B Department of Fish & Game and the Department of of Department the and Game & Fish of Department Big Pond Otis 125 B properties and recreational activities, visit the the visit activities, recreational and properties customize and print maps. mass.gov/dfw/wildlife-lands maps. print and customize Center Pond Becket 147 C For interactive maps and information on other other on information and maps interactive For Cheshire Lake Cheshire 210 B displays all MassWildlife properties and allows you to to you allows and properties MassWildlife all displays Cheshire Lake-Farnams Causeway Cheshire 273 F Wildlife Lands Maps – The MassWildlife Lands Viewer Viewer Lands MassWildlife The – Maps Lands Wildlife Cranberry Pond West Stockbridge 233 C Commonwealth’s properties and recreation activities.