A Water Preparedness Guide for State Action a Water Preparedness Guide for State Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programming NOAA Weather Radio

Why Do I Need a NOAA Weather Radio? ⦿ NOAA Weather Radio is an "All Hazards" radio network, making it your single source for comprehensive weather and emergency information. ⦿ One of the quickest and most reliable way to get life saving weather and emergency alerts from government and public safety officials. ⦿ NWR is provided as a public service by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), part of the Department of Commerce. What Features Do Weather Radios Have? ⦿ Tone alarm ⦿ S.A.M.E. Technology ⦿ Selectable alerting of events ⦿ Battery backup ● In the event of a power outage the radio will still work with the batteries ⦿ External antenna jack ⦿ Can be hooked up to attention getting devices ● Strobe lights, pagers, bed shakers, computers, text printers Where Should They Be Kept? ⦿ Near a window in a home or office. ● Receive better reception ⦿ It is a good idea to keep one with sports equipment for emergency alerts. ⦿ Everyone should take one with them while outdoors (boating, camping) or traveling. Getting to Know Your NWR 3 4 1. Programming Buttons 2 2. Select 2 5 3. Menu 1 1 4. Warning Light-Red 6 5. Watch Light- Orange 6. Advisory Light- Yellow 7 7. Weather Radio On/Off Switch 8 8. Volume Up/Down 9 9. Weather/Snooze Button Getting to Know Your NWR: Display Icons 1. Low Battery 3 4 5 Indicator 2 6 1 7 2. Menu Indicator 3. Weather Radio On Indicator 4. Warning Tone Alert 5. Voice Alert 6. Clock Alarm 7. Volume Level Bars 8 8. Alphanumeric Starting Your NWR 1. -

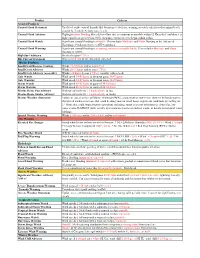

KJAX 2018 Product Criteria.Xlsx

Product Criteria Coastal Products Coastal Flood Statement Used to describe coastal hazards that do not meet advisory, warning or watch criteria such as minor beach erosion & elevated (Action) water levels. Coastal Flood Advisory Highlight minor flooding like tidal overflow that is imminent or possible within 12 Hours& if confidence is high (equal to or greater than 50%), then may extend or set to begin within 24 hrs. Coastal Flood Watch Significant coastal flooding is possible. This includes Moderate and Major flooding in the Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service (AHPS) product. Coastal Flood Warning Significant coastal flooding is occurring, imminent or highly likely. This includes Moderate and Major flooding in AHPS. High Surf Advisory Breaker heights ≥ 7 Feet Rip Current Statement When a high risk of rip currents is expected Marine Products Small Craft Exercise Caution Winds 15-20 knots and/or seas 6 Feet Small Craft Advisory Winds 20-33 knots and/or seas ≥ 7 Feet Small Craft Advisory (seas only) Winds< 20 knots & seas ≥ 7 Feet (usually with a swell) Gale Watch Wind speed 34-47 knots or frequent gusts 34-47 knots Gale Warning Wind speed 34-47 knots or frequent gusts 34-47 knots Storm Watch Wind speed 48-63 knots or gusts of 48-63 knots Storm Warning Wind speed 48-63 knots or gusts of 48-63 knots Marine Dense Fog Advisory Widespread visibility < 1 nautical mile in fog Marine Dense Smoke Advisory Widespread visibility < 1 nautical mile in smoke Marine Weather Statement Update or cancel at Special Marine Warning (SMW), a statement on non-severe showers & thunderstorms, short-lived wind/sea increase that could be dangerous for small boats, significant conditions prevailing for 2+ Hours that could impact marine operations including: rough seas near inlets/passes, dense fog, low water events, HAZMAT spills, rapidly increasing/decreasing or shifting winds, or details on potential water landings. -

Understanding and Improving Public Response to National Weather Service’S Coastal Flood Forecasts

FINAL REPORT Understanding and improving public response to National Weather Service’s coastal flood forecasts Prepared by Nurture Nature Center and RMC Research Corporation, 2015 for the New Jersey Sea Grant Consortium and National Sea Grant College Program, NOAA, U.S. Department of Commerce. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 INTRODUCTION 3 METHODOLOGY 4 Focus Group Process 4 Characteristics of the Study Sites 5 FINDINGS 6 Pre-Session Survey Findings: Participant Characteristics and Flooding Experiences 6 Demographics 6 Previous Flood Experience and Responses 7 Information Sources Consulted 8 Typical Actions Taken in the Face of Severe Weather 8 USE AND SALIENCE OF BRIEFING PACKAGES 9 DETAILED FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS OF NWS PRODUCTS 9 NWS Briefing Packages 9 Round 1 Briefing Discussion (Residents) 10 Emergency Personnel Briefing Discussion 12 Round 2 Briefing Discussion (Residents) 12 Survey Responses to Briefing Packages 16 Other NWS Coastal Flood Forecast Products 17 National Hurricane Center Track Forecast Cone 17 Weather Prediction Center Surface Prognosis Map (Renamed Surface Weather Patterns for Round 2) 18 NWS Precipitation Forecast Map (Renamed 5-Day Precipitation Forecast Map) 20 Extratropical Surge Forecast (Renamed Observed and Forecast Water Levels for Round 2) 22 Weather Forecast Office Wind Speed/ Wind Gust Forecast 24 NWS Coastal Flood Watch/ Flood Warning 26 NWS Temperature Forecast Map 28 NWS Low Tracks Ensemble Product 28 OTHER SURVEY FINDINGS 29 Barriers to Using NWS Products 29 Preferences for -

Owners Guide

Owners Guide Model 74-250(C) Digital Weather Receiver with NWR-SAME decoding, thermometer and Digital clock with 2 alarms PRODUCT INFORMATION The 74-250 N.W.R./ S.A.M.E. (National Weather Radio/Specific Area Message Encoding) Weather/All Hazard Monitor provides you with constant monitoring of your local National Weather Service broadcast for messages warning you of hazardous conditions. The NWR/SAME decoding allows you to hear only messages concerning the area concerning you. You now have a choice as to what information will be brought to you. No more will you be awakened to hear of a problem many miles from your home that will not affect you. A clock with alarm is also featured. The 74-250 NWR/SAME Weather/All Hazard Monitor is the latest advance in Weather monitoring technology providing you with the information you need for your greatest safety from the effects of weather and other external hazards. FEATURES: • VHF Weather Monitor with seven different National Weather Service channels in the 162 MHz FM band – Provides 24- hour-a-day National Weather Service information from seven different channels for maximum reception possible (in areas where available) • Alert monitor system receives NWR/SAME codes transmitted by National Weather Service stations warning of dangerous weather conditions and other general hazards. The SAME codes designate which counties or parts of counties are affected by the individual message. When the alert feature is activated, the receiver remains in a standby mode. As SAME coded messages are received, the receiver automatically activates to warn you of dangerous weather conditions. -

C:\My Documents\Research&Training

4.2A UTILIZING THE WEATHER FORECAST OFFICE HYDROLOGIC FORECAST SYSTEM FOR COASTAL FLOOD OPERATIONS David R. Vallee and James Notchey NOAA/National Weather Service Forecast Office Taunton, Massachusetts, 02780 1. INTRODUCTION by reading installed staff gages at predefined locations along the coastline. These elevation will be entered The Weather Forecast Office (WFO) Hydrologic directly into WHFS for incorporation into event assessment Forecast System (WHFS) provides an integrated suite of and product issuance. This network of staff gages in hydrologic software which is used by National Weather under development at the time of this writing. Service offices to more efficiently collect, analyze and monitor hydrologic conditions throughout its service area 2.2 Astronomical tide predictions ( NWS 2001). Data are received by satellite and phone communication, decoded, then placed into the hydrologic Hourly data sets of astronomical tide predictions, database for further interrogation and inclusion into daily out to 72 hours, are provided by the NOS for all primary products, watches and warnings. With the advent of stations and encoded in SHEF and disseminated by HADS telemetered tide gaging networks along the coast of to WFOs. Astronomical tide predictions for secondary Rhode Island and Massachusetts, WHFS can be stations are created through a local applications which configured to monitor tide data, including observations, utilizes a harmonic tide prediction scheme from the Xtide astronomical tide forecasts and extra tropical storm surge freeware package (Flater 1997) to determine the tide guidance. These data can then be incorporated into predictions. Additional information on this freeware detailed coastal flood watches and warnings, greatly package can be found at http://www.flaterco.com/xtide. -

Tactical Flood Response Plan Part One

OFFICIAL Tactical Flood Response Plan Part One Version 5.1 Author NRF Severe Weather & Flood Risk Group Reviewed by NRF Severe Weather & Flood Risk Authorised by Environment Agency Next review date June 2018 OFFICIAL Page 1 of 65 OFFICIAL Foreword This document has been produced after consultation with Category 1 and 2 Responders (as defined within the Civil Contingencies Act 2004), through the Norfolk Resilience Forum. It provides guidance by which Norfolk can be suitably prepared to respond to an actual or potential major flooding emergency, whereby the combined resources of numerous agencies are required. It will be used by these agencies when information is received or events occur that require a coordinated response at the tactical level. Tom McCabe NRF Executive Lead – Protection Capability Workstream Norfolk County Council OFFICIAL Page 2 of 65 OFFICIAL Table of Contents Foreword .............................................................................................................................................................................................2 Purpose ...............................................................................................................................................................................................8 Local Considerations: ........................................................................................................................................................................8 Protocols .............................................................................................................................................................................................9 -

10-320 Surf Zone Forecast and Coastal/Lakeshore Hazard Services

Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE INSTRUCTION 10-320 MAY 14, 2020 Operations and Services Marine And Coastal Weather Services, NWSPD 10-3 SURF ZONE FORECAST AND COASTAL/LAKESHORE HAZARD SERVICES NOTICE: This publication is available at: http://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/. OPR: W/AFS26 (J. Kuhn) Certified by: W/AFS26 (M. Angove) Type of Issuance: Unscheduled SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This instruction supersedes NWSI 10-320, “Surf Zone Forecast and Coastal/Lakeshore Hazard Services”, dated December 30, 2019. This instruction includes the following changes: Updated sections 2.3.3, 2.4, 2.6, 2.7 for reformatting of the Surf Zone Forecast Updated Appendix A Surf Zone Forecast examples. Digitally signed by STERN.ANDREW STERN.ANDREW.D.1382920348 .D.1382920348 Date: 2020.04.30 12:09:45 -04'00' 4/30/2020 Andrew D. Stern Date Director, Analyze, Forecast, and Support Office NWSI 10-320 MAY 14, 2020 Surf Zone Forecast and Coastal/Lakeshore Hazard Services Table of Contents: Page 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 4 2 Surf Zone Forecast (product category SRF) ............................................................................ 4 2.1 Mission Connection .......................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Issuance Guidelines ......................................................................................................... -

Blizzard Warning for CT Coast; Wind and 10-16 Inches of Snow Forecast; Cttransit Suspending Bus Service

Darienite News for Darien https://darienite.com Blizzard Warning for CT Coast; Wind and 10-16 Inches of Snow Forecast; CTTransit Suspending Bus Service Author : David Gurliacci Categories : Weather Tagged as : January 2016 Blizzard Date : January 23, 2016 The National Weather Service has issued a Blizzard Warning for most of the New York Metropolitan region and Connecticut's Long Island Coast and says Darien could be under 10 to 16 inches of snow through Saturday night, with blustery winds and dangerous travel conditions. Traveling roads could be "extremely dangerous" and the wind could cause power outages, the weather service says in the Blizzard Warning issued at 4 a.m. and in effect through 7 a.m. Sunday: EXTREMELY DANGEROUS TRAVEL DUE TO HEAVY SNOWFALL AND STRONG WINDS WITH WHITEOUT CONDITIONS LIKELY. SECONDARY AND TERTIARY ROADS MAY BECOME I MPASSABLE. STRONG WINDS MAY DOWN POWER LINES AND TREE LIMBS. 1 / 8 Darienite News for Darien https://darienite.com If an event in town has been scheduled for Saturday, assume it's cancelled. Report Any Downed Wires and Power Outages An update at 8:40 p.m. — Eversource has announced: "Remember: Always stay away from downed lines & report to 9-1-1. Report power outages to 1-800-286-2000 or online." UPDATES here: 5:22 p.m.: Here's the Latest Darien-specific forecast from the National Weather Service as of 3;56 p.m.: This Afternoon Snow. The snow could be heavy at times. Some thunder is also possible. High near 30. Wind chill values between 15 and 20. Windy, with a northeast wind around 33 mph. -

National Weather Service Warning Thresholds

NWS WARNINGS AND ADVISORIES FOR SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND (Last Updated: December 4, 2015) The following are National Weather Service criteria for issuing Watches/Warnings/Advisories: Watches: 50% confidence of meeting Warning criteria (generally within 36-48+ hours). Advisories and Warnings: 80% confidence in the event occurrence (generally within 24-36 hours). TYPE OF ISSUANCE WHEN ISSUED FOR SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND WINTER WEATHER ADVISORY More than one predominant hazard • Winter weather event having more than one predominant hazard (ie., snow and ice, snow and sleet, or snow, ice & sleet) meeting or exceeding advisory criteria for at least one of the precipitation elements, but remaining below warning criteria. Snow, Ocean Effect Snow, and/or Sleet • 3 inches averaged over a forecast zone in 12 hours (except 4 inches in Berkshire/Litchfield Counties) Snow and Blowing Snow • Sustained or frequent gusts of 25 to 34 mph accompanied by falling and blowing snow occasionally reducing visibility to ≤ 1/4 mile for ≥ 3 hours ` Blowing Snow • Widespread or localized blowing snow reducing visibility to ≤ ¼ mile with winds < 35 mph Black Ice • A Special Weather Statement will usually be issued when sufficient moisture is expected to cause a thin layer of ice on road surfaces, typically on cloudless nights (“black ice”). At forecaster discretion a formal Winter Weather Advisory may be issued instead. FREEZING RAIN ADVISORY Any accretion of freezing rain or freezing drizzle on road surfaces WIND CHILL ADVISORY Wind chill index between -15°F and -24°F for at least 3 hours using only the sustained wind WINTER STORM WARNING More than one predominant hazard • Winter weather event having more than one predominant hazard {ie. -

Department of Commerce $ National Oceanic

Department of Commerce • National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration • National Weather Service NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE INSTRUCTION 10-1710 February 1, 2018 Operations and Services Dissemination Policy NWSPD 10-17 NOAA WEATHER RADIO ALL HAZARDS (NWR) DISSEMINATION NOTICE: This publication is available at: https://www.nws.noaa.gov/directives/. OPR: W/DIS (C. Hodan) Certified by: W/DIS (Kevin C. Cooley) Type of Issuance: Routine SUMMARY OF REVISIONS: This directive supersedes NWSI 10-1710, “NOAA Weather Radio (NWR) Dissemination,” dated October 1, 2002. Changes were made to reflect the NWS Headquarters reorganization effective April 1, 2015. Content changes were made to: 1. Directive Name Change to NOAA Weather Radio All Hazards (NWR) Dissemination 2. Remove Console Replacement System (CRS) and the Voice Improvement Processor (VIP) 3. Add Broadcast Message Handler (BMH) 4. Remove “Backup Live;” function does not exist in current BMH configuration 5. Add BMH Practice Mode for proficiency requirements 6. Change RWT to be issued between “10:00am and 1:00pm. 7. Add length of record retention for message, system and error logs 8. Add procedures for recovery after an inadvertent alert is transmitted 9. Update numerous references to be consistent with other NWS documents 10. Update Appendix F to delete references to red-bordered envelope containing approved text of nuclear attack warning. 11. Change Appendix G to add NWR and Specific Area Message Encoding (SAME) relationship to the Emergency Alert System (EAS); and expand guidance on use of alert tones and Program Interrupt for SAME and EAS events __/signed/_______________________ 1/18/18 Kevin C. Cooley Date Acting Director, Office of Dissemination NWSI 10-1710 February 1, 2018 NOAA Weather Radio All Hazards (NWR) Dissemination Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................ -

Section 5.4-5.4.2

SECTION 5.4: RISK ASSESSMENT – HAZARDS PROFILES AND VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT 5.4 HAZARDS PROFILES AND VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT The following sections profile and assess vulnerability for each hazard of concern. For each hazard, the profile includes: the hazard description; its location and extent; previous occurrences and losses; and the probability of future events. The vulnerability assessment for each hazard includes: an overview of vulnerability; the data and methodology used; the impact on life, health and safety; impact on general building stock; impact on critical facilities; impact on the economy; additional data needs and next steps; and the overall vulnerability assessment finding. Hazards are presented in hazard priority order, starting with the coastal storm hazard and ending with the earthquake hazard. DMA 2000 Hazard Mitigation Plan – City of New Rochelle, New York 5.4-1 September 2010 SECTION 5.4.1: COASTAL AND SEVERE STORMS 5.4.1 COASTAL AND SEVERE STORMS This section provides a profile and vulnerability assessment for the coastal storm and severe storm hazards. HAZARD PROFILE Hazard profile information is provided in this section, including information on description, extent, location, previous occurrences and losses and the probability of future occurrences within the City of New Rochelle. Description Coastal storms (hurricanes, tropical depressions, tropical storms, and Nor’Easters) are typically events associated with severe storms (hailstorms, windstorms, lightning, thunderstorms and tornadoes). Therefore, for the purpose of this HMP, severe storms and coastal storms are grouped together. Both types of storms affect the City of New Rochelle. Severe Storm The severe storm hazard includes the following types of events: hailstorms, windstorms, lightning, thunderstorms and tornadoes. -

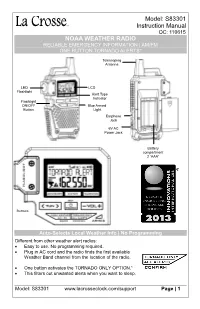

Model: S83301 Instruction Manual DC: 110615 NOAA WEATHER RADIO RELIABLE EMERGENCY INFORMATION | AM/FM ONE BUTTON TORNADO ALERTS*

Model: S83301 Instruction Manual DC: 110615 NOAA WEATHER RADIO RELIABLE EMERGENCY INFORMATION | AM/FM ONE BUTTON TORNADO ALERTS* Telescoping Antenna LED LCD Flashlight Alert Type Indicator Flashlight ON/OFF Blue Armed Button Light Earphone Jack 6V AC Power Jack Battery compartment 3 “AAA” Buttons Auto-Selects Local Weather Info | No Programming Different from other weather alert radios: • Easy to use. No programming required. • Plug in AC cord and the radio finds the first available Weather Band channel from the location of the radio. • One button activates the TORNADO ONLY OPTION.* • This filters out unwanted alerts when you want to sleep. Model: S83301 www.lacrosseclock.com/support Page | 1 Get Started Step 1: Insert the included 6-volt AC power adapter into the wall outlet then into the weather radio. Step 2 (Optional): Insert 3 new “AAA” batteries (not included) into the radio. Observe the correct polarity. Step 3: The radio automatically searches for the first available weather band channel for 30 seconds. Press the TORNADO ONLY / ALL ALERTS button to confirm the channel. Note: If the radio does not immediately turn on, press the POWER button one time. Easy One Button Alerts Selection: Tornado Only or All Alerts Select Tornado Only Alerts: • Filter out unwanted alerts when you want to sleep. • The NOAA Weather Radio will default to All Alerts. • One button will quickly select Tornado Only Alerts. 1. Press the TORNADO ONLY/ALL ALERTS button to toggle between Tornado Only Alerts and All NOAA Alerts. 2. Hold the TORNADO ONLY/ALL ALERTS button to enter (or exit) standby mode for either alert selection.