Brown Creeper Certhia Americana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Volcanic Vistas Discover National Forests in Central Oregon Summer 2009 Celebrating the Re-Opening of Lava Lands Visitor Center Inside

Volcanic Vistas Discover National Forests in Central Oregon Summer 2009 Celebrating the re-opening of Lava Lands Visitor Center Inside.... Be Safe! 2 LAWRENCE A. CHITWOOD Go To Special Places 3 EXHIBIT HALL Lava Lands Visitor Center 4-5 DEDICATED MAY 30, 2009 Experience Today 6 For a Better Tomorrow 7 The Exhibit Hall at Lava Lands Visitor Center is dedicated in memory of Explore Newberry Volcano 8-9 Larry Chitwood with deep gratitude for his significant contributions enlightening many students of the landscape now and in the future. Forest Restoration 10 Discover the Natural World 11-13 Lawrence A. Chitwood Discovery in the Kids Corner 14 (August 4, 1942 - January 4, 2008) Take the Road Less Traveled 15 Larry was a geologist for the Deschutes National Forest from 1972 until his Get High on Nature 16 retirement in June 2007. Larry was deeply involved in the creation of Newberry National Volcanic Monument and with the exhibits dedicated in 2009 at Lava Lands What's Your Interest? Visitor Center. He was well known throughout the The Deschutes and Ochoco National Forests are a recre- geologic and scientific communities for his enthusiastic support for those wishing ation haven. There are 2.5 million acres of forest including to learn more about Central Oregon. seven wilderness areas comprising 200,000 acres, six rivers, Larry was a gifted storyteller and an ever- 157 lakes and reservoirs, approximately 1,600 miles of trails, flowing source of knowledge. Lava Lands Visitor Center and the unique landscape of Newberry National Volcanic Monument. Explore snow- capped mountains or splash through whitewater rapids; there is something for everyone. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Meghan Powell Meghan Sunset view of White House Cove Marina in Poquoson Bibliography Bibliography Bibliography Adamcik, R.S., E.S. Bellatoni, D.C. DeLong, J.H. Schomaker, D.B Hamilton, M.K. Laubhan, and R.L. Schroeder. 2004. Writing Refuge Management Goals and Objectives: A Handbook. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Geological Survey. Atlantic Coast Joint Venture (ACJV). 2005. North American Waterfowl Management Plan. Atlantic Coast Joint Venture Waterfowl Implementation Plan Revision June 2005. Accessed September 2016 at: http://acjv.org/planning/waterfowl-implementation-plan/. —. 2007. New England/Mid-Atlantic Coast Bird Conservation Region (BCR) 30 Implementation Plan. Accessed September 2016 at: http://www.acjv.org/documents/BCR30_June18_07_final_draft.pdf. —. 2008. New England/Mid-Atlantic Coast Bird Conservation Region (BCR) 30 Implementation Plan. Accessed September 2016 at: http://www.acjv.org/BCR_30/BCR30_June_23_2008_final.pdf. —. 2009. Atlantic Coast Joint Venture Strategic Plan 2009 Update. Accessed September 2016 at: http://acjv.org/documents/ACJV_StrategicPlan_2009update_final.pdf. Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (AFWA). 2009. Voluntary Guidance for States to Incorporate Climate Change into State Wildlife Action Plans and Other Management Plans. Washington, D.C. Atwood, J.L. and P.R. Kelly. 1984. Fish dropped on breeding colonies as indicators of least tern food habits. Wilson Bulletin 96:34–47. Accessed September 2016 at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4161869. Baker, P.J., M. Dorcas, and W. Roosenburg. 2012. Malaclemys terrapin. In: IUCN 201X. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Balazik, M.T. and J.A. Musick. 2015. Dual annual spawning races in Atlantic sturgeon. PLoS One 10(5):e0128234. -

Colorado Birds the Colorado Field Ornithologists’ Quarterly

Vol. 50 No. 4 Fall 2016 Colorado Birds The Colorado Field Ornithologists’ Quarterly Stealthy Streptopelias The Hungry Bird—Sun Spiders Separating Brown Creepers Colorado Field Ornithologists PO Box 929, Indian Hills, Colorado 80454 cfobirds.org Colorado Birds (USPS 0446-190) (ISSN 1094-0030) is published quarterly by the Col- orado Field Ornithologists, P.O. Box 929, Indian Hills, CO 80454. Subscriptions are obtained through annual membership dues. Nonprofit postage paid at Louisville, CO. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Colorado Birds, P.O. Box 929, Indian Hills, CO 80454. Officers and Directors of Colorado Field Ornithologists: Dates indicate end of cur- rent term. An asterisk indicates eligibility for re-election. Terms expire at the annual convention. Officers: President: Doug Faulkner, Arvada, 2017*, [email protected]; Vice Presi- dent: David Gillilan, Littleton, 2017*, [email protected]; Secretary: Chris Owens, Longmont, 2017*, [email protected]; Treasurer: Michael Kiessig, Indian Hills, 2017*, [email protected] Directors: Christy Carello, Golden, 2019; Amber Carver, Littleton, 2018*; Lisa Ed- wards, Palmer Lake, 2017; Ted Floyd, Lafayette, 2017; Gloria Nikolai, Colorado Springs, 2018*; Christian Nunes, Longmont, 2019 Colorado Bird Records Committee: Dates indicate end of current term. An asterisk indicates eligibility to serve another term. Terms expire 12/31. Chair: Mark Peterson, Colorado Springs, 2018*, [email protected] Committee Members: John Drummond, Colorado Springs, 2016; Peter Gent, Boul- der, 2017*; Tony Leukering, Largo, Florida, 2018; Dan Maynard, Denver, 2017*; Bill Schmoker, Longmont, 2016; Kathy Mihm Dunning, Denver, 2018* Past Committee Member: Bill Maynard Colorado Birds Quarterly: Editor: Scott W. Gillihan, [email protected] Staff: Christy Carello, science editor, [email protected]; Debbie Marshall, design and layout, [email protected] Annual Membership Dues (renewable quarterly): General $25; Youth (under 18) $12; Institution $30. -

Behavioral Thermoregulation by Treecreepers: Trade-Off Between Saving Energy and Reducing Crypsis

Ecology, 82(6), 2001, pp. 1642±1654 q 2001 by the Ecological Society of America BEHAVIORAL THERMOREGULATION BY TREECREEPERS: TRADE-OFF BETWEEN SAVING ENERGY AND REDUCING CRYPSIS LUIS M. CARRASCAL,1,3 JOSE A. DõÂAZ,2 DANIEL L. HUERTAS,2 AND INGRID MOZETICH1 1Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (CSIC), Jose GutieÂrrez Abascal 2, E-28006 Madrid, Spain 2Departamento de BiologõÂa Animal I (Vertebrados), Facultad de BiologõÂa, Universidad Complutense, E-28040 Madrid, Spain Abstract. We studied the effect of solar radiation on the winter biology of Short-toed Treecreepers Certhia brachydactyla inhabiting a montane forest in Spain. We hypothesized that, in temperate latitudes of cold winter climate, with low cloudiness and under windless conditions, birds should select sunlit sites (i.e., forest sectors or trunk patches with high levels of exposure to sunlight) to reduce the metabolic cost of thermoregulation. At a within- habitat scale, a hypothesis of ``only metabolic bene®ts'' predicts that birds should select sunlit patches at shade temperatures (Tshade) below the birds' lower critical temperature (Tlc). They should shift to a random use of sunlit and shaded patches at temperatures above Tlc. Alter- natively, there could be added costs (e.g., travel costs, predation risk) in using sunlit patches. If higher visibility leads to diminished crypsis at sunlit patches (``trade-off with predation risk'' hypothesis), birds should select only shaded patches at Tshade values above Tlc (to enhance crypsis). They should increasingly select sunlit patches as Tshade decreases below Tlc. Treecreepers were selective in their use of sun±shade patches, across different spatial scales. At the among-plots scale, treecreeper abundance was positively related to the avail- ability of sunlit trunks, after we controlled for the effects of tree density, prey availability, and altitude. -

Creating a Songbird Remix Bird with Poser Or DAZ Studio 5 Using Conforming Crests with Poser 6 Using Conforming Crests with DAZ Studio 8

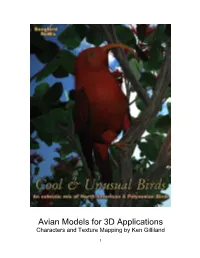

Avian Models for 3D Applications Characters and Texture Mapping by Ken Gilliland 1 Songbird ReMix Cool & Unusual Birds Contents Manual Introduction 3 Overview and Use 3 Conforming Crest Quick Reference 4 Creating a Songbird ReMix Bird with Poser or DAZ Studio 5 Using Conforming Crests with Poser 6 Using Conforming Crests with DAZ Studio 8 Field Guide List of Species 9 Baltimore Oriole 10 Brown Creeper 11 Curve-billed Thrasher 12 Greater Roadrunner 13 ’I’iwi 14 Oak Titmouse 15 ‘Omao 17 Red-breasted Nuthatch 18 Red Crossbill 19 Spotted Towhee 20 Western Meadowlark 21 Western Scrub-Jay 22 Western Tanager 23 White-crowned Sparrow 24 Resources, Credits and Thanks 25 Opinions expressed on this booklet are solely that of the author, Ken Gilliland, and may or may not reflect the opinions of the publisher, DAZ 3D. 2 Songbird ReMix Cool & Unusual Manual & Field Guide Copyrighted 2006-2011 by Ken Gilliland SongbirdReMix.com Introduction Songbird ReMix 'Cool and Unusual' Birds is an eclectic collection of birds from North America and the Hawaiian Islands. 'Cool and Unusual' Birds adds many new colorful and specialized bird species such as the Red Crossbill, whose specialized beak that allow the collection of pine nuts from pine cones, or the Brown Creeper who can camouflage itself into a piece of bark and the Roadrunner who spends more time on foot than on wing. Colorful exotics are also included like the crimson red 'I'iwi, a Hawaiian honeycreeper whose curved beak is a specialized for feeding on Hawaiian orchids, the Orange and Black Baltimore Oriole, who has more interest in fruit orchards than baseball diamonds and the lemon yellow songster, the western meadowlark who could be coming soon to a field fence post in your imagery. -

42. Chickadees, Nuthatches, Titmouse and Brown Creeper These Woodland Birds Are Mainly Year-Round Residents in Their Breeding Areas

42. Chickadees, Nuthatches, Titmouse and Brown Creeper These woodland birds are mainly year-round residents in their breeding areas. They become most apparent in fall and winter when all four types may occasionally be seen together, along with downy woodpeckers and kinglets, in mixed-species foraging flocks. In these groupings, the greater number of eyes may improve foraging efficiency and detect potential predators. Pennsylvania’s two chickadee species and the tufted titmouse belong to Family Paridae—omnivorous feeders that cache excess seeds in holes or bark crevices, remember the locations, and return later to eat the food. The two nuthatch species are in Family Sittidae. They glean insect food from the trunks of trees and also eat nuts. Their common name derives from the way they “hack” nuts apart using their stout pointed bills. Taxonomists place the brown creeper in Family Certhiidae, a group that includes ten species, eight of which inhabit Europe and Asia and another India and Africa. The brown creeper is the only species of this family found in black-capped North America. chickadee Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) — A black cap and bib, buffy flanks, and a white belly mark this small (five eat wild berries and the seeds of various plants including inches long), spunky bird. Chickadees have short, sharp ragweed, goldenrod and staghorn sumac. Seeds and the bills and strong legs that let them hop about in trees and eggs and larvae of insects are important winter staples. cling to branches upside down while feeding. They fly in In the fall, chickadees begin storing food in bark crevices, an undulating manner, with rapid wingbeats, rarely going curled leaves, clusters of pine needles, and knotholes. -

Status of the Brown Creeper (Certhia Americana) in Alberta

Status of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) in Alberta Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 49 Status of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) in Alberta Prepared for: Alberta Sustainable Resource Development (SRD) Alberta Conservation Association (ACA) Prepared by: Kevin Hannah This report has been reviewed, revised, and edited prior to publication. It is an SRD/ACA working document that will be revised and updated periodically. Alberta Wildlife Status Report No. 49 June 2003 Published By: i Publication No. T/047 ISBN: 0-7785-2917-7 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-2918-5 (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1206-4912 (Printed Edition) ISSN: 1499-4682 (On-line Edition) Series Editors: Sue Peters and Robin Gutsell Illustrations: Brian Huffman For copies of this report,visit our web site at : http://www3.gov.ab.ca/srd/fw/riskspecies/ and click on “Detailed Status” OR Contact: Information Centre - Publications Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Division Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 - 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment/Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 - 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-6424 This publication may be cited as: Alberta Sustainable Resource Development. 2003. Status of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) in Alberta. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, and Alberta Conservation Association, Wildlife Status Report No. 49, Edmonton, AB. 30 pp. ii PREFACE Every five years, the Fish and Wildlife Division of Alberta Sustainable Resource Development reviews the status of wildlife species in Alberta. These overviews, which have been conducted in 1991, 1996 and 2000, assign individual species “ranks” that reflect the perceived level of risk to populations that occur in the province. -

Brown Creeper September 2016 Certhia Americana

National Park Service Klamath Network Featured Creature U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship & Science Klamath Network Brown Creeper September 2016 Certhia americana Field Notes crevices in the bark of trees. Beetles, raptors in the genus Accipiter ants, spiders, and pseudoscorpions equipped with short wings and long are common prey. Deeply furrowed tails for maneuvering in dense forest bark is a gold mine for these birds, conditions. Squirrels, deer mice, and which explains why they tend to other rodents will take eggs and young inhabit older forests containing large from the nest. trees that have had to time to develop thick bark. For nesting, they rely on Reproduction another feature of older forest: snags, Beginning in April or May, the female or standing dead trees. In the West, builds her nest behind a loose flap of they tend to occur in coniferous or bark against the trunk of a tree, mixed forests, but can also inhabit typically a snag. The base layer is orchards, woodlands, forested coarser twigs and bark held together floodplains, and swamps. by insect cocoons and spider-egg cases, forming a sort of “sling.” The Behavior and Life History nest cup is made of finer material such Brown creepers spend most of their as wood fibers, hair, feathers, grass, time in motion, foraging. Starting at lichens, and mosses. The female lays the base of a tree, they move upward, 4–8 white eggs, speckled with pink or Brown creeper. Photo: Tom Talbott, Creative Commons. often in a spiral, probing and picking reddish-brown spots at the large end. -

Taxonomy of the Brown Creeper in California. In: Dickerman, R.W

TAXONOMY OF THE BROWN CREEPER IN CALIFORNIA PHILIP UNITT1 and AMADEO M. REA2 Ab s t r a c t . — Three subspecies of the Brown Creeper breed in California: C. a. zelotes, from the inner Coast Range of northern California east to the Warner Mountains and south through the Sierra Nevada, Transverse, and Peninsular ranges, has a dark cinna mon rump, a dusky brown crown and back narrowly streaked whitish, and white under parts. C. a. occidentalis from the humid coast belt from the Oregon border south to Marin and Alameda counties: has a dark cinnamon rump, a deep rufous crown and back nar rowly streaked buff, and white underparts. C. a. phillipsi, new subspecies, of the central coast from San Mateo to San Luis Obispo counties, has a golden cinnamon rump, a deep rufous crown and back narrowly streaked whitish and smoke gray, and grayish brown underparts. Two additional subspecies occur as rare winter visitors: C. a. montana, breed ing in the Rocky Mountains and known in California from five specimens; has a paler tawny rump, a relatively pale crown and back with broad white streaks but little rufous, and white underparts. C. a. americana, breeding in eastern North America and known in California from four specimens: has also a pale tawny rump, a relatively pale crown with broad buff-tinted whitish streaks, a broadly white-streaked back with much rufous, usu ally white underparts (sometimes tinted pale peach color), and a tendency to a shorter bill. Webster (1986) reviewed the subspecies of the Brown Creeper (Certhia americana) most recently. -

Birds of Norther America (2000), Atlas of Breeding Birds of Monterey County (1993) and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Website (Accessed 2011)

1 Facts on the bird species most commonly observed at the Preserve: Sources: The Sibley Guide to Birds of Norther America (2000), Atlas of Breeding Birds of Monterey County (1993) and The Cornell Lab of Ornithology website (Accessed 2011) 1. Spotted Towhee (Pipilo maculatus) This is a common permanent-resident seen and heard in all the habitat types on the preserve except the deep redwood canyon, however it is most abundantly in chaparral. It forages for food in the dense brush by scratching at the leaf litter with its powerful legs. In one scientific study, a male of this species was recorded singing continuously for 45 minutes! The males’ loud singing declines as the summer progresses and they become busy feeding the young, until the singing ends in early August. The song is described as having “0-8 identical introductory notes followed by a buzzy rapid trill.” 2. California Quail (Callipepla californica) “Chi-ca-go! Chi-ca-go!” is ironically the call of the state bird of California that you may hear while walking in the grassland/chaparral ecotone or oak woodland habitat. Quail are classified in the same family as chickens and pheasants. Quail populations are known to be highly variable depending on if it is a wet or dry year – in wet years, pairs will attempt to raise two sets of young sequencially. A group of quail is called a covey (“cuh-vee”) and ranges from about 10-30 individuals where multiple pairs of parents take care of the young collectively. At the preserve, you will most often see quail in parking lot area.