Aga Khan Iii and the British Empire: the Ismailis In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environment and Development AGA KHAN FOUNDATION

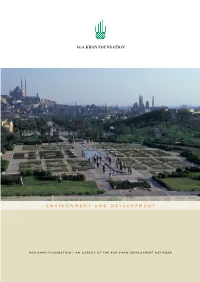

AGA KHAN FOUNDATION E N V I R ON ME NT A ND D EVEL O PME NT AG A K H A N F O U N D AT I O N – A N A G E N C Y O F TH E A G A K H A N D EVEL O PME NT N E T W O RK 1 COver: AL-AZHar Park, CAIRO, EGypT THE CREATION OF A PARK FOR THE CITIZENS OF THE EGYPTIAN CAPITAL, ON A 30-HECTARE (74-ACRE) MOUND OF RUBBLE ADJACENT TO THE HISTORIC CITY, HAS EVOLVED WELL BEYOND THE GREEN SPACE OF THE PARK TO INCLUDE A VARIETY OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC INITIATIVES IN THE NEIGHBOURING DARB AL-AHMAR DISTRICT. THE PARK ITSELF ATTRACTS AN AVERAGE OF 3,000 PEOPLE A DAY AND AS MANY AS 10,000 DAILY DURING RAMADAN. 2 CONTENTS 2 Foreword 3 About the Aga Khan Foundation 5 The Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan Fund for the Environment Case Studies: 9 • A “Green Lung” for Cairo 10 • Environmental Water and Sanitation 11 • Reforestation and Land Reclamation 12 • Environmentally Friendly Tourism Infrastructure 14 • Water Conservation 16 • Sustainable Energy for Developing Economies 18 • Fuel-Saving Stoves and Healthier Houses 19 • A University for Development in Mountain Environments 20 Environmental Awards for AKDN Programmes 24 About Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan and His Highness the Aga Khan 24 About the Aga Khan Development Network 26 AKDN Partners in Environment and Development 1 FOREWORD RiGHT: QESHLAQ-I-BAIKH VILLAGE, AFGHANISTAN IN recent Years, A DROught has COmpOunded difficulties EXperienced due TO the large-scale destructiON OF the agricultural infrastruc- ture and the sudden influX OF Afghan returnees frOM ABROad. -

Presentation by Abel Fernandes De Assis, Ministry of Education of Mozambique

REPÚBLICA DE MOÇAMBIQUE MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO International Literacy Day “All Children Reading” Washington, 8 September 2011 2 Outline presentation: Education in Mozambique Context, priorities and objectives Progress and challenges (EMIS data) Measuring learning outcomes: current status Different studies The case of Cabo Delgado (Aga Khan Study) SACMEQ (II and III) Improving learning outcomes: future implications Stronger focus on quality interventions Strengthening the management of the education system Focus on Monitoring (Learning )Achievements Major challenges 3 EDUCATION IN MOZAMBIQUE Priorities, progress and challenges 4 Education in Mozambique: Context, priorities, objectives Education key to combating poverty and increase (economic) development; First priority concerns the provision of seven-year primary education of quality for all children (commitment to the MDGs); At the same time, recognizing the importance of other levels of education, the sector prepares for their expansion within the parameters of existing (institutional and financial) capacity to ensure quality and sustainability. 5 Progress: exponential expansion at all level Number of students, Primary Education, day school, public Nº of students per class, 2004 and 2011, all school types 6 Progress: equity and quality indicators • Increased equity in gender in primary and secondary education • Less untrained teachers • Reduced pupil/teacher ratio, but still high. 7 Challenge: Increase in drop-out (5th and 7th grade) 8 Progress: reduction of illiteracy -

Backgrounder Global Centre for Pluralism Mission

Global Centre for Pluralism: Backgrounder Global Centre for Pluralism Mission: The Global Centre for Pluralism serves as a global platform for comparative analysis, education and dialogue about the choices and actions that advance and sustain pluralism. Vision: The Centre’s vision is a world where human differences are valued and diverse societies thrive. The Global Centre for Pluralism is an independent, charitable organization created to advance positive responses to the challenge of living peacefully and productively together in diverse societies. Why Canada Founded in Ottawa by His Highness the Aga Khan in partnership with the Government of Canada, the Centre takes inspiration from Canada’s experience. Respect for diversity has developed into a defining characteristic of Canada and a core element of the country’s identity. Although still a work in progress, Canada is a global leader in the way it has valued and managed its diverse multi-ethnic, multicultural fabric. The Centre’s headquarters will be a platform for analysing and sharing Canada’s ongoing pluralism journey with the world. His Highness the Aga Khan His Highness the Aga Khan is the 49th hereditary Imam (Spiritual Leader) of the Shia Imami Ismaili Muslims. For His Highness the Aga Khan, one manifestation of his hereditary responsibilities has been a deep engagement with development for almost 60 years. Ties with Canada: His Highness has long been interested in Canada’s experience of pluralism. His close ties with Canada go back almost four decades to the 1970s when many thousands of Asian refugees expelled from Uganda, including many Ismailis, were welcomed into Canadian society. -

![Diamond Jubilee His Highness the Aga Khan Iv [1957 – 2017]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5083/diamond-jubilee-his-highness-the-aga-khan-iv-1957-2017-145083.webp)

Diamond Jubilee His Highness the Aga Khan Iv [1957 – 2017]

DIAMOND JUBILEE HIS HIGHNESS THE AGA KHAN IV [1957 – 2017] . The Diamond Jubilee What is the Diamond Jubilee? The Diamond Jubilee marks the 60th anniversary of His Highness the Aga Khan’s leadership as the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslim Community. On 11th July, 1957, the Aga Khan, at the age of 20, assumed the hereditary office of Imam established by Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family), following the passing of his grandfather, Sir Sultan Mahomed Shah Aga Khan. Why is the Community celebrating His Highness the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee? The commemoration of the Aga Khan’s Diamond Jubilee is in keeping with the Ismaili Community’s longstanding tradition of marking historic milestones. Over the past six decades, the Aga Khan has transformed the quality of life of hundreds of millions of people around the world. In the areas of health, education, cultural revitalisation, and economic empowerment, he has inspired excellence and worked to improve living conditions and opportunities in some of the world’s most remote and troubled regions. The Diamond Jubilee is an opportunity for the Shia Ismaili Muslim community, partners of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), and government and faith community leaders in over 25 countries to express their appreciation for His Highness’s leadership and commitment to improve the quality of life of the world’s most vulnerable populations. It is also an occasion for His Highness to recognise the friendship and longstanding support of leaders of governments and partners in the work of the Imamat and to set the direction for the future. -

Nutritional Influences on the Health of Women and Children in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique: a Qualitative Study

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Nutritional Influences on the Health of Women and Children in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique: A Qualitative Study Adelaide Lusambili 1,2,*, Violet Naanyu 1, Gibson Manda 3, Lindsay Mossman 4 , Stefania Wisofschi 1, Rachel Pell 4, Sofia Jadavji 4 , Jerim Obure 1 and Marleen Temmerman 1 1 Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health, Aga Khan University, Nairobi P.O. Box 30270-00100, Kenya; [email protected] (V.N.); [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (J.O.); [email protected] (M.T.) 2 Department of Population Health, Aga Khan University, Nairobi P.O. Box 30270-00100, Kenya 3 Aga Khan Foundation Mozambique, Maputo P.O. Box 746, Mozambique; [email protected] 4 Aga Khan Foundation, Ottawa, ON K1N 1K6, Canada; [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (R.P.); Sofi[email protected] (S.J.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 July 2020; Accepted: 13 August 2020; Published: 27 August 2020 Abstract: In 2017, the Government of Mozambique declared localized acute malnutrition crises in a range of districts across Mozambique including Cabo Delgado. This is in spite of intensive efforts by different non-governmental organizations (NGO) and the Government of Mozambique to expand access to information on good nutritional practices as well as promote nutrition-specific interventions, such as cooking demonstrations, home gardens and the distribution of micronutrient powder to children. This paper examines and discusses key nutritional influences on the health of pregnant and breastfeeding mothers in Cabo Delgado province, Mozambique. We conducted 21 key informant interviews (KIIs) with a wide range of stakeholders and 16 in-depth interviews (IDIs) with women. -

Longines Turf Winner Notes- Owner, Aga Khan

H.H. Aga Khan Born: Dec. 13, 1936, Geneva, Switzerland Family: Children, Rahim Aga Khan, Zahra Aga Khan, Aly Muhammad Aga Khan, Hussain Aga Khan Breeders’ Cup Record: 15-2-0-2 | $3,447,400 • Billionaire, philanthropist and spiritual leader, Prince Karim Aga Khan IV is also well known as an owner and breeder of Thoroughbreds. • Has two previous Breeders’ Cup winners – Lashkari (GB), captured the inaugural running of Turf (G1) in 1984 and Kalanisi (IRE) won 2000 edition of race. • This year, is targeting the $4 million Longines Turf with his good European filly Tarnawa (IRE), who was also cross-entered for the $2 million Maker’s Mark Filly & Mare Turf (G1) after earning an automatic entry via the Breeders’ Cup Challenge “Win & You’re In” series upon winning Longines Prix de l’Opera (G1) Oct. 4 at Longchamp. Perfect in three 2020 starts, the homebred also won Prix Vermeille (G1) in September. • Powerhouse on the international racing stage. Has won the Epsom Derby five times, including the record 10-length victory in 1981 by the ill-fated Shergar (GB), who was famously kidnapped and never found. In 2000, Sinndar (IRE) became the first horse to win Epsom Derby, Irish Derby (G1) and Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe (G1) the same season. In 2008, his brilliant unbeaten filly Zarkava (IRE) won the Arc and was named Europe’s Cartier Horse of the Year. • Trainers include Ireland-based Dermot Weld, Michael Halford and beginning in 2021 former Irish champion jockey Johnny Murtagh, who rode Kalanisi to his Breeders’ Cup win, and France-based Alain de Royer-Dupre, Jean-Claude Rouget, Mikel Delzangles and Francis-Henri Graffard • Almost exclusively races homebreds but is ever keen to acquire new bloodlines, evidenced by acquisition of the late Francois Dupre's stock in 1977, the late Marcel Boussac’s in 1978 and Jean-Luc Lagardere’s in 2005. -

Islam in Kenya: the Khoja Ismilis

INSTITUTE OF CURRENT VJORLD AFFAIRS DER- 31 & 32 November 26, 1954 Islam in Kenya c/o Barclays Bank Introduction Queeusway Nairobi, Kenya Mr. Walter S. Rogers (Delayed fr revl sl Institute of Current World Affairs 522 Fifth Avenue New York 36, New York Dear Mr. Roers: All over the continent of Africa, from Morocco and Egypt to Zanzibar, Cape Town and Nigeria, millions of eople respond each day to a ringing cry heard across half the world for 1300 years. La i.l.aha illa-'llah: Muhmmadun rasulm,'llh, There is no God but Allah and Muhammad is his Prophet By these words, Muslims declare their faith in the teachings of the Arabian Prophet. The religion was born in Arabia and the words of its declaration of faith are in Arabic, but Islam has been accepted by many peoples of various races, natioual- i tie s and religious back- grounds, includiu a diverse number iu Kenya. Iu this colony there are African, Indian, Arab, Somali, Comoriau and other Muslims---even a few Euglishmeu---aud they meet each Frlday for formal worship in mosques iu Nairobi, Mombasa, Lamu and Kisumu, in the African Resewves and across the arid wastes of the northern frontier desert. Considerable attention has been given to the role of Christianity in Kenya and elsewhere iu East Africa, Jamia (Sunni) Mosque, and rightly so. But it Nairobl is sometimes overlooked that another great mouo- theistic religiou is at work as well. Islam arose later iu history than Christianity, but it was firmly planted lu Kenya centuries before the first Christian missionaries stepped ashore at Mombasa. -

The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: a Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966 Azizeddin Tejpar University of Central Florida Part of the African History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Tejpar, Azizeddin, "The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6324. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6324 THE MIGRATION OF INDIANS TO EASTERN AFRICA: A CASE STUDY OF THE ISMAILI COMMUNITY, 1866-1966 by AZIZEDDIN TEJPAR B.A. Binghamton University 1971 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2019 Major Professor: Yovanna Pineda © 2019 Azizeddin Tejpar ii ABSTRACT Much of the Ismaili settlement in Eastern Africa, together with several other immigrant communities of Indian origin, took place in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries. This thesis argues that the primary mover of the migration were the edicts, or Farmans, of the Ismaili spiritual leader. They were instrumental in motivating Ismailis to go to East Africa. -

The Fatimid Caliphate General Editor: Farhad Daftary Diversity of Traditions

'lltc Jnslitutc of lsmaili Studies Ismaili Heritage Series, 14 The Fatimid Caliphate General Editor: Farhad Daftary Diversity of Traditions Previously published titles: I. Paul E. Walker, Abu Ya'qub al-SijistiinI: Intellectual Missionary (1996) 2. Heinz Halm, The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning ( 1997) 3. Paul E. Walker, Jjamfd al-Din al-Kirmani: Ismaili Thought in the Age ofal-l:iiikim (1999) 4. Alice C. Hunsberger, Nasir Khusraw, The Ruby of Badakhshan: A Portrait of the Persian Poet, Traveller and Philosopher (2000) 5. Farouk Mitha, Al-Ghazalf and the Ismailis: A Debate in Medieval Islam (2001) Edited by 6. Ali S. Asani, Ecstasy and Enlightenment: The Ismaili Devotional Literature of South Asia (2002) Farhad Daftary and Shainool Jiwa 7. Paul E. Walker, Exploring an Islamic Empire: Fatimid History and its Sources (2002) 8. Nadia Eboo Jamal, Surviving the Mongols: Nizari Quhistani and the Continuity ofIsmaili Tradition in Persia (2002) 9. Verena Klemm, Memoirs of a Mission: The Ismaili Scholar; States man and Poet al-Mu'ayyad fi'l-Din al-Shfriizi (2003) 10. Peter Willey, Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria (2005) 11. Sumaiya A. Hamdani, Between Revolution and State: The Path to Fatimid Statehood (2006) 12. Farhad Daftary, Ismailis in Medieval Muslim Societies (2005) 13. Farhad Daftary, ed., A Modern History of the Ismailis (2011) I.B.Tauris Publishers LONDON • NEW YORK in association with The Institute oflsmaili Studies LONDON 1111 '1111' 1'itti111icl <: 11lifih111t· soun;cs and fanciful accounts of medieval times. 'lhus legends and misconceptions have continued to surround the Ismailis through the 20th century. -

Overview of the Aga Khan Foundation

brings them into federated structures and links them with local governments through collaboration on development issues. It also provides fund-raising advice and contacts through its civil society activities. Most AKF activities are implemented by effectively managed, local organisations interested in testing new solutions, in learning from experience and in being agents of lasting change. However, if no established group exists, AKF occasionally establishes new organisations to AGA KHAN FOUNDATION tackle particularly important issues. AKF generally maintains long-term involvement in building social institutions, and thus is able to make commitments to communities as well as carry through changes in attitudes, behaviours and organisational abilities, which require a longer time horizon. Overview of the Aga Khan Foundation Learning and evaluation AKF projects are designed to contribute lessons towards understanding complex issues and identifying potential solutions for adaptation to conditions in different regions. AKF measures success when beneficiaries report improvements in their lives, and when the processes which led to these improvements serve as useful models in other places. Wherever relevant, approaches are tested primarily in rural settings but also in some urban settings, and within different cultural and geographic environments. Evaluation and dissemination are equally essential. International teams, collaboratively with implementers, conduct reviews at agreed intervals in the project cycle. The conclusions are shared with AKF affiliates, beneficiaries and interested governmental and non-governmental organisations. Valuable lessons are brought to the attention of policymakers to enhance decision making, and to the public to raise awareness of important issues facing developing countries. FACTS AT A GLANCE Information for partners FOUNDED IN: 1967 The Foundation is largely an implementing organisation rather than a grant-making THEMATIC FOCUS: Rural develop- foundation. -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

Islam and the Abolition of Slavery in the Indian Ocean

Proceedings of the 10th Annual Gilder Lehrman Center International Conference at Yale University Slavery and the Slave Trades in the Indian Ocean and Arab Worlds: Global Connections and Disconnections November 7‐8, 2008 Yale University New Haven, Connecticut Islamic Abolitionism in the Western Indian Ocean from c. 1800 William G. Clarence‐Smith, SOAS, University of London Available online at http://www.yale.edu/glc/indian‐ocean/clarence‐smith.pdf © Do not cite or circulate without the author’s permission For Bernard Lewis, ‘Islamic abolitionism’ is a contradiction in terms, for it was the West that imposed abolition on Islam, through colonial decrees or by exerting pressure on independent states.1 He stands in a long line of weighty scholarship, which stresses the uniquely Western origins of the ending slavery, and the unchallenged legality of slavery in Muslim eyes prior to the advent of modern secularism and socialism. However, there has always been a contrary approach, which recognizes that Islam developed positions hostile to the ‘peculiar institution’ from within its own traditions.2 This paper follows the latter line of thought, exploring Islamic views of slavery in the western Indian Ocean, broadly conceived as stretching from Egypt to India. Islamic abolition was particularly important in turning abolitionist laws into a lived social reality. Muslim rulers were rarely at the forefront of passing abolitionist legislation, 1 Bernard Lewis, Race and slavery in the Middle East, an historical enquiry (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990) pp. 78‐84. Clarence‐Smith 1 and, if they were, they often failed to enforce laws that were ‘for the Englishman to see.’ Legislation was merely the first step, for it proved remarkably difficult to suppress the slave trade, let alone slavery itself, in the western Indian Ocean.3 Only when the majority of Muslims, including slaves themselves, embraced the process of reform did social relations really change on the ground.