Wildlife of the Isle of Wight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Environment Action Plan the Undercliff

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan The Undercliff Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for the Undercliff. INTRODUCTION This HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography, land use and settlement patterns which differentiate it from other HEAP areas. This document identifies essential characteristics of the Undercliff as its geomorphology and rugged landslip areas, its archaeological potential, its 19 th century cottages ornés /marine villas and their grounds, and the Victorian seaside resort character of Ventnor. The Area has a highly distinctive character with an inner cliff towering above a landscape (now partly wooded) demarcated by stone boundary walls. The most significant features of this historic landscape, the most important forces for change and key management issues are considered. Actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT Location, Geology and Topography • The Undercliff is identified as a discrete Landscape Character Type in the Isle of Wight AONB Management Plan (2004, 132). • The Area lies to the south of the South Wight Downland , from which it is separated by vertical cliffs forming a geological succession from Ferrugunious Sands through Sandrock, Carstone, Gault Clay, Upper Greensand, Chert Beds and Lower Chalk (Hutchinson 1987, Fig. 6). o The zone between the inner cliff and coastal cliff is a landslip area o This landslip is caused by groundwater lubrication of slip planes within the Gault Clays and Sandrock Beds. -

Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for West Wight Chalk Downland. INTRODUCTION The West Wight Chalk Downland HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography and historic landscape character. It forms the western half of a central chalk ridge that crosses the Isle of Wight, the eastern half having been defined as the East Wight Chalk Ridge . Another block of Chalk and Upper Greensand in the south of the Isle of Wight has been defined as the South Wight Downland . Obviously there are many similarities between these three HEAP Areas. However, each of the Areas occupies a particular geographical location and has a distinctive historic landscape character. This document identifies essential characteristics of the West Wight Chalk Downland . These include the large extent of unimproved chalk grassland, great time-depth, many archaeological features and historic settlement in the Bowcombe Valley. The Area is valued for its open access, its landscape and wide views and as a tranquil recreational area. Most of the land at the western end of this Area, from the Needles to Mottistone Down, is open access land belonging to the National Trust. Significant historic landscape features within this Area are identified within this document. The condition of these features and forces for change in the landscape are considered. Management issues are discussed and actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. -

Land at Borthwood Lane | Newchurch | Sandown | PO36 OHH Guide Price £48,000

Land at Borthwood Lane | Newchurch | Sandown | PO36 OHH Guide Price £48,000 An area of land which extends to approximately 5 acres and is Freehold. The land is currently Approximately 5 Acres of pasture and has easy access to the Island's extensive bridleway network. The land is partly Land hedged and fenced. The neighbouring Borthwood Copse (National Trust) is a Site of Important Currently used as Pasture Nature Conservation (S.I.N.C.) and is home to many species of wildlife including the Island's Land well-known red squirrels. Access to Bridleways Secure gated entrance Property Description From Newport take the A3056 signal to Sandown. Proceed through Arreton an at Thompson Nursery and turn left into An area of land which extends to approximately 5 acres and is Watery Lane. At the cross roads go straight ahead into Forest Freehold. The land is currently pasture and has easy access to the Island's extensive bridleway network. The land is partly hedged and Road and then left into Alverstone Road. Do not turn left into fenced. The neighbouring Borthwood Copse (National Trust) is a Site Skinners Hill; Borthwood Lane will be found on the right hand of Important Nature Conservation (S.I.N.C.) and is home to many side. Turn into the lane and the Land will be found on the right species of wildlife including the Island's well-known red squirrels. side after 300m Newchurch Newchurch is a very popular village in the south east of the Viewing arrangements Island about 8 miles from Island’s main shopping and Viewing is strictly by appointment with the Sole Agents Biles & administrative centre of Newport. -

Neolithic & Early Bronze Age Isle of Wight

Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Resource Assessment The Isle of Wight Ruth Waller, Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service September 2006 Inheritance: The map of Mesolithic finds on the Isle of Wight shows concentrations of activity in the major river valleys as well two clusters on the north coast around the Newtown Estuary and Wooton to Quarr beaches. Although the latter is likely due to the results of a long term research project, it nevertheless shows an interaction with the river valleys and coastal areas best suited for occupation in the Mesolithic period. In the last synthesis of Neolithic evidence (Basford 1980), it was claimed that Neolithic activity appears to follow the same pattern along the three major rivers with the Western Yar activity centred in an area around the chalk gap, flint scatters along the River Medina and greensand activity along the Eastern Yar. The map of Neolithic activity today shows a much more widely dispersed pattern with clear concentrations around the river valleys, but with clusters of activity around the mouths of the four northern estuaries and along the south coast. As most of the Bronze Age remains recorded on the SMR are not securely dated, it has been difficult to divide the Early from the Late Bronze Age remains. All burial barrows and findspots have been included within this period assessment rather than the Later Bronze Age assessment. Nature of the evidence base: 235 Neolithic records on the County SMR with 202 of these being artefacts, including 77 flint or stone polished axes and four sites at which pottery has been recovered. -

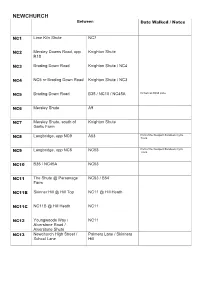

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes NC1 Lime Kiln Shute NC7 NC2 Mersley Downs Road, opp Knighton Shute R18 NC3 Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC4 NC4 NC5 nr Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC3 NC5 Brading Down Road B35 / NC10 / NC45A Known as Blind Lane NC6 Mersley Shute A9 NC7 Mersley Shute, south of Knighton Shute Garlic Farm Langbridge, opp NC9 A53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC8 Track Langbridge, opp NC8 NC53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC9 Track NC10 B35 / NC45A NC53 NC11 The Shute @ Parsonage NC53 / B54 Farm NC11B Skinner Hill @ Hill Top NC11 @ Hill Heath NC11C NC11B @ Hill Heath NC11 NC12 Youngwoods Way / NC11 Alverstone Road / Alverstone Shute NC13 Newchurch High Street / Palmers Lane / Skinners School Lane Hill NC14 Palmers Lane Dyers Lane Path obstructed not walkable NC15 Skinners Hill Alverstone Road NC16 Winford Road Alverstone Road NC17 Alverstone Main Road, opp Burnthouse Lane / NC44 Alverstone squirrel hide NC42 / youngwoods Way NC18 Burnthouse Lane / NC44 SS48 NC19 Alverstone Road NC20 / NC21 NC20 Alverstone Road / SS54 @ Cheverton Farm Borthwood Copse Borthwood Lane campsite NC21 Alverstone Road NC19 / NC20 / NC21 NC22 Borthwood Lane, opp NC19 NC22A @ Embassy Way Sandown airport @ Beaulieu Cottages runway ________________ SS30 @ Scotchells Brook SS28 @ Sandown Air Port NC22A NC22 / NC22B @ Embassy NC22 / SS25 Way Scotchells Brook Lane / NC22 / NC22A Known as Embassy Way – Sandown NC22B airport NC23 @ Embassy Way NC23 Borthwood Lane, opp Scotchells Brook Lane / SS57 NC24 Hale Common (A3056) @ Winford -

2017 City of York Biodiversity Action Plan

CITY OF YORK Local Biodiversity Action Plan 2017 City of York Local Biodiversity Action Plan - Executive Summary What is biodiversity and why is it important? Biodiversity is the variety of all species of plant and animal life on earth, and the places in which they live. Biodiversity has its own intrinsic value but is also provides us with a wide range of essential goods and services such as such as food, fresh water and clean air, natural flood and climate regulation and pollination of crops, but also less obvious services such as benefits to our health and wellbeing and providing a sense of place. We are experiencing global declines in biodiversity, and the goods and services which it provides are consistently undervalued. Efforts to protect and enhance biodiversity need to be significantly increased. The Biodiversity of the City of York The City of York area is a special place not only for its history, buildings and archaeology but also for its wildlife. York Minister is an 800 year old jewel in the historical crown of the city, but we also have our natural gems as well. York supports species and habitats which are of national, regional and local conservation importance including the endangered Tansy Beetle which until 2014 was known only to occur along stretches of the River Ouse around York and Selby; ancient flood meadows of which c.9-10% of the national resource occurs in York; populations of Otters and Water Voles on the River Ouse, River Foss and their tributaries; the country’s most northerly example of extensive lowland heath at Strensall Common; and internationally important populations of wetland birds in the Lower Derwent Valley. -

Location Address1 Address2 Address3 Postcode Asset Type

Location Address1 Address2 Address3 Postcode Asset Type Description Tenure Alverstone Land Alverstone Shute Alverstone PO36 0NT Land Freehold Alverstone Grazing Land Alverstone Shute Alverstone PO36 0NT Grazing Land Freehold Arreton Branstone Farm Study Centre Main Road Branstone PO36 0LT Education Other/Childrens Services Freehold Arreton Stockmans House Main Road Branstone PO36 0LT Housing Freehold Arreton St George`s CE Primary School Main Road Arreton PO30 3AD Schools Freehold Arreton Land Off Hazley Combe Arreton PO30 3AD Non-Operational Freehold Arreton Land Main Road Arreton PO30 3AB Schools Leased Arreton Land Arreton Down Arreton PO30 2PA Non-Operational Leased Bembridge Bembridge Library Church Road Bembridge PO35 5NA Libraries Freehold Bembridge Coastguard Lookout Beachfield Road Bembridge PO35 5TN Non-Operational Freehold Bembridge Forelands Middle School Walls Road Bembridge PO35 5RH Schools Freehold Bembridge Bembridge Fire Station Walls Road Bembridge PO35 5RH Fire & Rescue Freehold Bembridge Bembridge CE Primary Steyne Road Bembridge PO35 5UH Schools Freehold Bembridge Toilets Lane End Bembridge PO35 5TB Public Conveniences Freehold Bembridge RNLI Life Boat Station Lane End Bembridge PO35 5TB Coastal Freehold Bembridge Car Park Lane End Forelands PO35 5UE Car Parks Freehold Bembridge Toilets Beach Road / Station Road Bembridge PO35 5NQ Public Conveniences Freehold Bembridge Toilet High Street Bembridge PO35 5SE Public Conveniences Freehold Bembridge Toilets High Street Bembridge PO35 5SD Public Conveniences Freehold Bembridge -

English Nature Research Report

Maritime Natural Area: MIO. Whitstable to Geological Significance: Notable North Foreland (provisional) General geologicaVgeomorpholugicaIcharactcr: The Whitstable to North Foreland Maritime Natural Area has a varied coastline with relatively low-lying coast in thc cast rising to boulder clay and chalk cliffs towards the Isle of Thanet. Geological Htrtory: This coastline is characterised by the Cretaceous chalk of the Isle oTThanet bounded to the west by clays, silts and sands of the Lower ‘I’ertiary. Upper Cretaceous Santonian chalk (87-83 Ma) is exposed dipping gently to the west from Margatc to the eastern side of Herne Bay. Unconformably overlying the chalk is a sequence of Lower Tertiary scdiments which are exposed in I Ierne Bay; the Palaeocenc Thanet, Woolwicli and Oldhaven Formations overlain by the Eocene London Clay Formation. The Chalk was deposited by a shallow sea which covered much of Northwestern Europe towards the end of the Cretaceous. Sea lcvel fall was followed by the unconformabie deposition of Tertiary Palaeocene and Ikcene sedirnents. Dominantly marine in origin, these scdiments were deposited by a rising, but fluctuating sea, which covered much of Southeast England. Marine conditions were well established by the Eocene leading to the deposition ofthe i,ondon Clay Formation. Thc fossil fauna and flora from the Tertiary rocks indicates a gradually warming climate with sub-tropical conditions established by the Eocene. Subsequent uplilt (associated with the Alpine Orogeny) and resultant erosion removed much of the remaining Tertiary sediments, the next deposition occurring during the Pleistocene. Though not covercd by ice, the area was affectcd by periglacial erosion in a tundra-like environment during the last glaciation (Devensian). -

Phragmites Australis

Journal of Ecology 2017, 105, 1123–1162 doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12797 BIOLOGICAL FLORA OF THE BRITISH ISLES* No. 283 List Vasc. PI. Br. Isles (1992) no. 153, 64,1 Biological Flora of the British Isles: Phragmites australis Jasmin G. Packer†,1,2,3, Laura A. Meyerson4, Hana Skalov a5, Petr Pysek 5,6,7 and Christoph Kueffer3,7 1Environment Institute, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; 2School of Biological Sciences, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia; 3Institute of Integrative Biology, Department of Environmental Systems Science, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) Zurich, CH-8092, Zurich,€ Switzerland; 4University of Rhode Island, Natural Resources Science, Kingston, RI 02881, USA; 5Institute of Botany, Department of Invasion Ecology, The Czech Academy of Sciences, CZ-25243, Pruhonice, Czech Republic; 6Department of Ecology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, CZ-12844, Prague 2, Czech Republic; and 7Centre for Invasion Biology, Department of Botany and Zoology, Stellenbosch University, Matieland 7602, South Africa Summary 1. This account presents comprehensive information on the biology of Phragmites australis (Cav.) Trin. ex Steud. (P. communis Trin.; common reed) that is relevant to understanding its ecological char- acteristics and behaviour. The main topics are presented within the standard framework of the Biologi- cal Flora of the British Isles: distribution, habitat, communities, responses to biotic factors and to the abiotic environment, plant structure and physiology, phenology, floral and seed characters, herbivores and diseases, as well as history including invasive spread in other regions, and conservation. 2. Phragmites australis is a cosmopolitan species native to the British flora and widespread in lowland habitats throughout, from the Shetland archipelago to southern England. -

Bosco Palazzi

SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología ISSN: 0300-5267 ISSN: 2340-4078 [email protected] Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Bella, S; Parenzan, P.; Russo, P. Diversity of the Macrolepidoptera from a “Bosco Palazzi” area in a woodland of Quercus trojana Webb., in southeastern Murgia (Apulia region, Italy) (Insecta: Lepidoptera) SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, vol. 46, no. 182, 2018, April-June, pp. 315-345 Sociedad Hispano-Luso-Americana de Lepidopterología España Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45559600012 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative SHILAP Revta. lepid., 46 (182) junio 2018: 315-345 eISSN: 2340-4078 ISSN: 0300-5267 Diversity of the Macrolepidoptera from a “Bosco Palazzi” area in a woodland of Quercus trojana Webb., in southeastern Murgia (Apulia region, Italy) (Insecta: Lepidoptera) S. Bella, P. Parenzan & P. Russo Abstract This study summarises the known records of the Macrolepidoptera species of the “Bosco Palazzi” area near the municipality of Putignano (Apulia region) in the Murgia mountains in southern Italy. The list of species is based on historical bibliographic data along with new material collected by other entomologists in the last few decades. A total of 207 species belonging to the families Cossidae (3 species), Drepanidae (4 species), Lasiocampidae (7 species), Limacodidae (1 species), Saturniidae (2 species), Sphingidae (5 species), Brahmaeidae (1 species), Geometridae (55 species), Notodontidae (5 species), Nolidae (3 species), Euteliidae (1 species), Noctuidae (96 species), and Erebidae (24 species) were identified. -

Insects Associated with Fruits of the Oleaceae (Asteridae, Lamiales) in Kenya, with Special Reference to the Tephritidae (Diptera)

D. Elmo Hardy Memorial Volume. Contributions to the Systematics and 135 Evolution of Diptera. Edited by N.L. Evenhuis & K.Y. Kaneshiro. Bishop Museum Bulletin in Entomology 12: 135–164 (2004). Insects associated with fruits of the Oleaceae (Asteridae, Lamiales) in Kenya, with special reference to the Tephritidae (Diptera) ROBERT S. COPELAND Department of Entomology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843 USA, and International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, Box 30772, Nairobi, Kenya; email: [email protected] IAN M. WHITE Department of Entomology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, UK; e-mail: [email protected] MILLICENT OKUMU, PERIS MACHERA International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology, Box 30772, Nairobi, Kenya. ROBERT A. WHARTON Department of Entomology, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843 USA; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Collections of fruits from indigenous species of Oleaceae were made in Kenya between 1999 and 2003. Members of the four Kenyan genera were sampled in coastal and highland forest habitats, and at altitudes from sea level to 2979 m. Schrebera alata, whose fruit is a woody capsule, produced Lepidoptera only, as did the fleshy fruits of Jasminum species. Tephritid fruit flies were reared only from fruits of the oleaceous subtribe Oleinae, including Olea and Chionanthus. Four tephritid species were reared from Olea. The olive fly, Bactrocera oleae, was found exclusively in fruits of O. europaea ssp. cuspidata, a close relative of the commercial olive, Olea europaea ssp. europaea. Olive fly was reared from 90% (n = 21) of samples of this species, on both sides of the Rift Valley and at elevations to 2801 m. -

Butterflies and Moths (Insecta: Lepidoptera) of the Lokrum Island, Southern Dalmatia

NAT. CROAT. VOL. 29 Suppl.No 2 1227-24051-57 ZAGREB DecemberMarch 31, 31, 2021 2020 original scientific paper / izvorni znanstveni rad DOI 10.20302/NC.2020.29.29 BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) OF THE LOKRUM ISLAND, SOUTHERN DALMATIA Toni Koren Association Hyla, Lipovac I 7, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia (e-mail: [email protected]) Koren, T.: Butterflies and moths (Insecta: Lepidoptera) of the Lokrum island, southern Dalmatia. Nat. Croat., Vol. 29, No. 2, 227-240, 2020, Zagreb. In 2016 and 2017 a survey of the butterflies and moth fauna of the island of Lokrum, Dubrovnik was carried out. A total of 208 species were recorded, which, together with 15 species from the literature, raised the total number of known species to 223. The results of our survey can be used as a baseline for the study of future changes in the Lepidoptera composition on the island. In comparison with the lit- erature records, eight butterfly species can be regarded as extinct from the island. The most probable reason for extinction is the degradation of the grassland habitats due to the natural succession as well as the introduction of the European Rabbit and Indian Peafowl. Their presence has probably had a tremendously detrimental effect on the native flora and fauna of the island. To conserve the Lepidop- tera fauna of the island, and the still remaining biodiversity, immediate eradication of these introduced species is needed. Key words: Croatia, Adriatic islands, Elafiti, invasive species, distribution Koren, T.: Danji i noćni leptiri (Insecta: Lepidoptera) otoka Lokruma, južna Dalmacija. Nat. Croat., Vol.