A Comprehensive Subsurface Investigation at Magnolia Plantation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighborwoods Right Plant, Right Place Plant Selection Guide

“Right Plant, Right Place” Plant Selection Guide Compiled by Samuel Kelleher, ASLA April 2014 - Shrubs - Sweet Shrub - Calycanthus floridus Description: Deciduous shrub; Native; leaves opposite, simple, smooth margined, oblong; flowers axillary, with many brown-maroon, strap-like petals, aromatic; brown seeds enclosed in an elongated, fibrous sac. Sometimes called “Sweet Bubba” or “Sweet Bubby”. Height: 6-9 ft. Width: 6-12 ft. Exposure: Sun to partial shade; range of soil types Sasanqua Camellia - Camellia sasanqua Comment: Evergreen. Drought tolerant Height: 6-10 ft. Width: 5-7 ft. Flower: 2-3 in. single or double white, pink or red flowers in fall Site: Sun to partial shade; prefers acidic, moist, well-drained soil high in organic matter Yaupon Holly - Ilex vomitoria Description: Evergreen shrub or small tree; Native; leaves alternate, simple, elliptical, shallowly toothed; flowers axillary, small, white; fruit a red or rarely yellow berry Height: 15-20 ft. (if allowed to grow without heavy pruning) Width: 10-20 ft. Site: Sun to partial shade; tolerates a range of soil types (dry, moist) Loropetalum ‘ZhuZhou’-Loropetalum chinense ‘ZhuZhou’ Description: Evergreen; It has a loose, slightly open habit and a roughly rounded to vase- shaped form with a medium-fine texture. Height: 10-15 ft. Width: 10-15ft. Site: Preferred growing conditions include sun to partial shade (especially afternoon shade) and moist, well-drained, acidic soil with plenty of organic matter Japanese Ternstroemia - Ternstroemia gymnanthera Comment: Evergreen; Salt spray tolerant; often sold as Cleyera japonica; can be severely pruned. Form is upright oval to rounded; densely branched. Height: 8-10 ft. Width: 5-6 ft. -

Indiana's Native Magnolias

FNR-238 Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources Know your Trees Series Indiana’s Native Magnolias Sally S. Weeks, Dendrologist Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 This publication is available in color at http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/fnr.htm Introduction When most Midwesterners think of a magnolia, images of the grand, evergreen southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) (Figure 1) usually come to mind. Even those familiar with magnolias tend to think of them as occurring only in the South, where a more moderate climate prevails. Seven species do indeed thrive, especially in the southern Appalachian Mountains. But how many Hoosiers know that there are two native species Figure 2. Cucumber magnolia when planted will grow well throughout Indiana. In Charles Deam’s Trees of Indiana, the author reports “it doubtless occurred in all or nearly all of the counties in southern Indiana south of a line drawn from Franklin to Knox counties.” It was mainly found as a scattered, woodland tree and considered very local. Today, it is known to occur in only three small native populations and is listed as State Endangered Figure 1. Southern magnolia by the Division of Nature Preserves within Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources. found in Indiana? Very few, I suspect. No native As the common name suggests, the immature magnolias occur further west than eastern Texas, fruits are green and resemble a cucumber so we “easterners” are uniquely blessed with the (Figure 3). Pioneers added the seeds to whisky presence of these beautiful flowering trees. to make bitters, a supposed remedy for many Indiana’s most “abundant” species, cucumber ailments. -

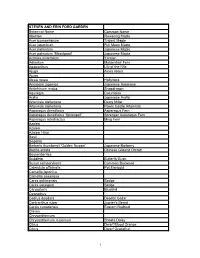

STEVEN and ERIN FORD GARDEN Botanical Name Common Name

STEVEN AND ERIN FORD GARDEN Botanical Name Common Name Abutilon Flowering Maple Acer buergerianum Trident Maple Acer japonicum Full Moon Maple Acer palmatum Japanese Maple Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple Achillea millefolium Yarrow Adiantum Maidenhair Fern Agapanthus Lily of the Nile Ajuga Alcea rosea Ajuga Alcea rosea Hollyhock Anemone japonica Japanese Anemone Antirrhinum majus Snapdragon Aquilegia Columbine Aralia Japanese Aralia Artemisia stelleriana Dusty Miller Artemisia stelleriana Powis Castle Artemisia Asparagus densiflorus Asparagus Fern Asparagus densiflorus 'Sprengeri' Sprenger Asparagus Fern Asparagus retrofractus Ming Fern Azalea Azalea Azalea 'Hino' Basil Begonia Berberis thumbergii 'Golden Nugget' Japanese Barberry Bletilla striata Chinese Ground Orchid Boysenberries Buddleja Butterfly Bush Buxus sempervirens Common Boxwood Calendula officinalis Pot Marigold Camellia japonica Camellia sasanqua Carex oshimensis Sedge Carex variegata Sedge Caryopteris Bluebird Ceanothus Cedrus deodara Deodar Cedar Centranthus ruber Jupiter's Beard Cercis canadensis Eastern Rudbud Chives Chrysanthemum Chrysanthemum maximum Shasta Daisy Citrus Dwarf Blood Orange Citrus Dwarf Grapefruit 1 Citrus Dwarf Tangerine Citrus Navel Orange Citrus Variegated Lemon Clematis Cornus Dogwood Cornus kousa Kousa Dogwood Cornus stolonifera Redtwig Dogwood Cotinus Smoke Tree Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria Cyathea cooperi Australian Tree Fern Cyclamen Delphinium Dianella tasmanica 'Yellow Stripe' Flax Lily Dianthus Pink Dianthus barbatus Sweet -

American Forests National Big Tree Program Species Without Champions

American Forests National Big Tree Program Champion trees are the superstars of their species — and there are more than 700 of them in our national register. Each champion is the result of a lucky combination: growing in a spot protected by the landscape or by people who have cared about and for it, good soil, the right amount of water, and resilience to the elements, surviving storms, disease and pests. American Forests National Big Tree Program was founded to honor these trees. Since 1940, we have kept the only national register of champion trees (http://www.americanforests.org/explore- forests/americas-biggest-trees/champion-trees-national-register/) Champion trees are found by people just like you — school teachers, kids fascinated by science, tree lovers of all ages and even arborists for whom a fun day off is measuring the biggest tree they can find. You, too, can become a big tree hunter and compete to find new champions. Species without Champions (March, 2018) Gold rows indict species that have Idaho State Champions but the nominations are too old to be submitted for National Champion status. Scientific Name Species Common Name Abies lasiocarpa FIR Subalpine Acacia macracantha ACACIA Long-spine Acacia roemeriana CATCLAW Roemer Acer grandidentatum MAPLE Canyon or bigtooth maple Acer nigrum MAPLE Black Acer platanoides MAPLE Norway Acer saccharinum MAPLE Silver Aesculus pavia BUCKEYE Red Aesculus sylvatica BUCKEYE Painted Ailanthus altissima AILANTHUS Tree-of-heaven Albizia julibrissin SILKTREE Mimosa Albizia lebbek LEBBEK Lebbek -

Magnolia 'Galaxy'

Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ The National Arboretum presents Magnolia ‘Galaxy’, unique in form and flower among cultivated magnolias. ‘Galaxy’ is a single-stemmed, tree-form magnolia with ascending branches, the perfect shape for narrow planting sites. In spring, dark red-purple flowers appear after danger of frost, providing a pleasing and long-lasting display. Choose ‘Galaxy’ to shape up your landscape! Winner of a Pennsylvania Horticultural Society Gold Medal Plant Award, 1992. U.S. National Arboretum Plant Introduction Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 3501 New York Ave. NE., Washington, DC 20002 ‘Galaxy’ hybrid magnolia Botanical name: Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ (M. liliiflora ‘Nigra’ × M. sprengeri ‘Diva’) (NA 28352.14, PI 433306) Family: Magnoliaceae Hardiness: USDA Zones 5–9 Development: ‘Galaxy’ is an F1 hybrid selection resulting from a 1963 cross between Magnolia liliiflora ‘Nigra’ and M. sprengeri ‘Diva’. ‘Galaxy’ first flowered at 9 years of age from seed. The cultivar name ‘Galaxy’ is registered with the American Magnolia Society. Released 1980. Significance: Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ is unique in form and flower among cultivated magnolias. It is a single stemmed, pyramidal, tree-form magnolia with excellent, ascending branching habit. ‘Galaxy’ flowers 2 weeks after its early parent M. ‘Diva’, late enough to avoid most late spring frost damage. Adaptable to a wide range of soil conditions. Description: Height and Width: 30-40 feet tall and 22-25 feet wide. It reaches 24 feet in height with a 7-inch trunk diameter at 14 years. Moderate growth rate. Habit: Single-trunked, upright tree with narrow crown and ascending branches. -

Magnolia X Soulangiana Saucer Magnolia1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-386 October 1994 Magnolia x soulangiana Saucer Magnolia1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Saucer Magnolia is a multi-stemmed, spreading tree, 25 feet tall with a 20 to 30-foot spread and bright, attractive gray bark (Fig. 1). Growth rate is moderately fast but slows down considerably as the tree reaches about 20-years of age. Young trees are distinctly upright, becoming more oval, then round by 10 years of age. Large, fuzzy, green flower buds are carried through the winter at the tips of brittle branches. The blooms open in late winter to early spring before the leaves, producing large, white flowers shaded in pink, creating a spectacular flower display. However, a late frost can often ruin the flowers in all areas where it is grown. This can be incredibly disappointing since you wait 51 weeks for the flowers to appear. In warmer climates, the late- flowering selections avoid frost damage but some are less showy than the early-flowered forms which blossom when little else is in flower. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Magnolia x soulangiana Figure 1. Middle-aged Saucer Magnolia. Pronunciation: mag-NO-lee-uh x soo-lan-jee-AY-nuh Common name(s): Saucer Magnolia DESCRIPTION Family: Magnoliaceae USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 9A (Fig. 2) Height: 20 to 25 feet Origin: not native to North America Spread: 20 to 30 feet Uses: container or above-ground planter; espalier; Crown uniformity: irregular outline or silhouette near a deck or patio; shade tree; specimen; no proven Crown shape: round; upright urban tolerance Crown density: open Availability: generally available in many areas within Growth rate: medium its hardiness range 1. -

![2018 Recommended Street Tree Species List San Francisco Urban Forestry Council Approved [Date]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4478/2018-recommended-street-tree-species-list-san-francisco-urban-forestry-council-approved-date-1484478.webp)

2018 Recommended Street Tree Species List San Francisco Urban Forestry Council Approved [Date]

2018 Recommended Street Tree Species List San Francisco Urban Forestry Council Approved [date] The Urban Forestry Council annually reviews and updates this list of trees in collaboration with public and non-profit urban forestry stakeholders, including San Francisco Public Works – Bureau of Urban Forestry and Friends of the Urban Forest. While this list recommends species that are known to do well in many locations in San Francisco, no tree is perfect for every potential tree planting location. This list should be used as a guideline for choosing which street tree to plant but should not be used without the help of an arborist or other tree professional. All street trees must be approved by Public Works before planting. The application form to plant a street tree can be found on their website: http://sfpublicworks.org/plant-street-tree Photo by Scott Szarapka on Unsplash 1 Section 1: Tree species, varieties, and cultivars that do well in most locations in San Francisco. Size Evergreen/ Species Notes Deciduous Small Evergreen Laurus nobilis ‘Saratoga’ Saratoga bay laurel Uneven performer, prefers heat, needs some Less than wind protection, susceptible to pests 20’ tall at Magnolia grandiflora ‘Little Gem’ Little Gem magnolia maturity Deciduous Crataegus phaenopyrum Washington hawthorn Subject to pests, has thorns, may be susceptible to fireblight. Medium Evergreen Agonis flexuosa (green) peppermint willow Standard green-leaf species only. ‘After Dark’ 20-35’ tall variety NOT recommended. Fast grower – at more than 12” annually, requires extensive maturity maintenance when young. Callistemon viminalis weeping bottlebrush Has sticky flowers Magnolia grandiflora ‘St. Mary,’ southern magnolia Melaleuca quinquenervia broad-leaf paperbark Grows fast, dense, irregular form, prefers wind protection Olea europaea (any fruitless variety) fruitless olive Needs a very large basin, prefers wind protection Podocarpus gracilior/Afrocarpus falcatus fern pine Slow rooter. -

Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees

Selecting juglone-tolerant plants Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees Black walnut trees (Juglans nigra) can be very attractive in the home landscape when grown as shade trees, reaching a potential height of 100 feet. The walnuts they produce are a food source for squirrels, other wildlife and people as well. However, whether a black walnut tree already exists on your property or you are considering planting one, be aware that black walnuts produce juglone. This is a natural but toxic chemical they produce to reduce competition for resources from other plants. This natural self-defense mechanism can be harmful to nearby plants causing “walnut wilt.” Having a walnut tree in your landscape, however, certainly does not mean the landscape will be barren. Not all plants are sensitive to juglone. Many trees, vines, shrubs, ground covers, annuals and perennials will grow and even thrive in close proximity to a walnut tree. Production and Effect of Juglone Toxicity Juglone, which occurs in all parts of the black walnut tree, can affect other plants by several means: Stems Through root contact Leaves Through leakage or decay in the soil Through falling and decaying leaves When rain leaches and drips juglone from leaves Nuts and hulls and branches onto plants below. Juglone is most concentrated in the buds, nut hulls and All parts of the black walnut tree produce roots and, to a lesser degree, in leaves and stems. Plants toxic juglone to varying degrees. located beneath the canopy of walnut trees are most at risk. In general, the toxic zone around a mature walnut tree is within 50 to 60 feet of the trunk, but can extend to 80 feet. -

Tree Litter Kevin Dunn

Tree Litter Kevin Dunn 1) Leaves What makes a particular species of tree messy while another one is considered clean? I count 5 factors: 1)Leaves a) Ideal Trees (Ginkgo and Oriental Spruce) Ginkgo Tree/Clean Tree Oriental Spruce/Clean Tree Leaves b) Winter Leaf Retention (Pin Oak and Shingle Oak) c) Leaves that decompose slowly (Evergreen Magnolias, Oaks, and Sycamores) vs Quick decomposers (Maples, Elms, and Tulip trees) Brackens Evergreen Magnolia Sycamore Sugar Maple Tulip Tree Princeton American Elm Leaves d) Leaf drop due to disease or environmental stress, disease resistant Crabapples, River Birch vs Prairie Gold Aspen Crabapple Tree River Birch Prairie Gold Aspen 2)Weak, brittle wood Many times, it’s the faster growing trees that produce the weakest wood. Silver maples, willows, Siberian elms, and Callery pears such as the Bradford are examples. These trees are all susceptible to breaking up from ice storms, thunderstorms, or high winds. Weak, brittle wood Consider planting slower growers with stronger wood such as Sugar maples, disease resistant cultivars of American elm such as Princeton, or parrotia also called Persian ironwood. Some of the slower growing native oaks have some of the strongest wood, e.g., burr oak which has stronger wood than the much faster growing pin oak. Parrotia Tree Burr Oak 3) Fruit Examples include acorns, pine cones, drupes (dogwood trees and hollies), aggregate of follicles (magnolia), samara (maple trees), a syncarp of drupes (hedge apple tree), berry-like pome (serviceberry), pome (crabapple), pod (locust trees, redbuds), gumballs (sweetgum tree) Nellie Stevens Holly Honey Locust Tree Fruit Birds and other animals often eat the fruit of some trees before it ever drops. -

Fall Line Magnolia Bogs of the Mid-Atlantic Region

nsua 74 Fall Line Magnolia Bogs of the Mid-Atlantic Region Rodedck Simmons end Nark Strong [Reprinted from the October zooz issue of Audubon Naturalist] Magnolia Bogs have long been regarded as one of the most inter- esting natural features in the Washington, D.C. area. W. L. McA- tee, a Washington area naturalist who first defined these bogs in r9rg, termed them "Magnolia Bogs" for the unique assemblage of sweetbay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana), Sphagnum moss, and other bog flora. Occasionally they are referred to as "McAteean Bogs, " after McAtee, or "Seepage Bogs. " These bogs usually form on hillsides or slopes where a spring or seep flows from an upland gravel and sand aquifer over a thick, impervious layer of underly- ing clay which prevents the downward infiltration of water. This seepage flow and the highly acidic, gravelly soils create optimal conditions for the formation of bogs. The term "bog" as applied here, although technically a misno- mer, has traditionally been used by people in general, including botanists, to describe acidic, sphagnous wetlands that strongly resemble bogs. Magnolia Bogs are actually acidic, fen-like seeps uniquely associated with high elevation gravel terraces of the inner Coastal Plain near the Fall Line, which divides the Coastal Plain and Piedmont physiographic provinces in the mid-Atlantic region. Their distribution generally follows the Fall Line in a nar- row east-west band from the Laurel area, at the northern extent of their range in Prince George's County, Maryland, to their southern extent near Fredericksburg, Virginia. Throughout their range, they were never common or very large, usually occupying an area an acre or less in size. -

Plant Guide Spring

Plant Guide Spring China is home to more than 30,000 plant species – one-eighth of the world’s total. At Lan Su, visitors can enjoy hundreds of these plants, many of which have a rich symbolic and cultural history in China. This guide is a selected look at some of Lan Su’s current favorites. Please return this guide to the Garden Host at the entrance when your visit is over. A Clematis G Magnolia* M Rhododendron* B Chinese Paper Bush H Lushan Honeysuckle N Winter Jasmine C Winter Daphne I Peony* O Kerria D Chinese Fringe Flower J Chinese Plum P Bergenia E Forsythia K Quince Q Iris F Camelllia* L Crabapple R Corydalis * For a complete list of these species, please request a master species list at the entrance. It is also available online at www.lansugarden.org/plants PLANT Guide Spring Clematis A Forsythia E (Clematis armandii ‘Appleblossom’, (Forsythia x intermedia ‘Lynwood Gold’) C. fasciculiflora) Long cultivated in Chinese gardens, C. armandii is native to China. Look forsythia has become popular in for the soft-pink, lightly fragrant gardens throughout the world. Cut ‘Apple Blossom’ cultivar above the branches can be forced to bloom early, moon gate. C. fasciculiflora is a rare when brought indoors. Chinese species with small, fragrant white flowers. Its young foliage has distinctive, silver center stripes. Chinese Paper B Camellia F Bush (Camellia. japonica ‘Drama Girl’) For additional camellia varieties, see the Master (Edgeworthia ‘Red Dragon’, E. chrysantha) Species List Native to China, this deciduous shrub is a relative of sweet Daphne. -

Street Tree ID Guide

Callery Pear Japanese Zelkova Schubert Cherry Eastern Redbud Little-Leaf Linden American Linden Pin Oak Northern Red Oak Teardrop Pyrus calleryana Zelkova serrata Spade Prunus virginiana Cercis canadensis neven Tilia cordata Tilia americana Oak Quercus palustris Quercus rubra Bark has Flowers and Leaves are lenticels; tree is Bark has fruit emerge directly Leaves Leaves Most common tough and waxy tightly vase-shaped lenticels from branches 2” - 4” long 5” - 6” long oak species in NYC Mulberry Katsura Tree Silver Linden Linden Fruits Japanese Treelilac Swamp White Oak White Oak English Oak Morus cultivar Cercidiphyllum japonicum Tilia tomentosa Syringa reticulata Quercus bicolor Quercus alba Quercus robur O All three Linden species Leaf shape Leaves in this guide have similar varies: may be 2” - 5” long; clusters of fragrant flowers mitten-shaped white and (which turn into seeds) Undersides of or have 3-5 lobes hairy underneath attached to a leaf-like blade leaves are fuzzy Elongated acorns Black Silver Cornelian Pagoda American Oklahoma Eastern Empress Paper American Elm Chinese Elm Common Hackberry Scarlet Bur Shumard Black Southern Birch Birch Cherry Dogwood Catalpa Beech Redbud Cottonwood Tree Birch Ulmus americana Ulmus parvifolia Celtis occidentalis Oak Oak Oak Oak Red Oak Betula Betula Cornus Cornus Catalpa Fagus Cercis Populus Paulownia Betula Quercus Quercus Quercus Quercus Quercus nigra pendula mas alterniflora cultivar grandifolia reniformis deltoides tomentosa papyrifera coccinea macrocarpa shumardii velutina falcata Long bean- Sandpapery Only like seed Bark peels off Weeping form; Dogwood with pods; big leaf; tricolor calico Sandpapery leaf; patchwork bark warty silver bark Bark is orange in papery sheets bark has lenticels O alternate leaves leaves O Smooth silver bark Gigantic leaves Bark has lenticels when scratched Osage Quaking Big-Tooth Cucumber Siberian Chinese Orange Aspen Aspen Magnolia Common Types of Tree Fruits and Seeds Elm Treelilac Image Sources: Kumar, Neeraj, Lawrence Barringer, Peter N.