India's Contribution to the Universal Declaration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

The Journal the Music Academy

ISSN. 0970-3101 THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. LX 1989 *ra im rfra era faw ifa s i r ? ii ''I dwell not,in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins nor in the Sun; (but) where my bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada!" Edited by: T. S. PARTHASARATHY The Music Academy Madras 306, T. T. K. Road, Madras-600014 Annual Subscription — Inland Rs. 20 : Foreign $ 3-00 OURSELVES This Journal is published as an Annual. All correspondence relating to the Journal should be addressed and all books etc., intended for it should be sent to The Editor, Journal of the Music Academy, 306, T. T. K. Road, Madras-600 014. Articles on music and dance are accepted for publication on the understanding that they are contributed solely to the Journal of the Music Academy. Manuscripts should be legibly written or, preferably, type written (double-spaced and on one side of the paper only) and should be signed by the writter (giving his or her address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by contributors in their articles. CONTENTS Pages The 62nd Madras Music Conference - Official Report 1-64 The Bhakta and External Worship (Sri Tyagaraja’s Utsava Sampradaya Songs) Dr. William J. Jackson 65-91 Rhythmic Analysis of Some Selected Tiruppugazh Songs Prof. Trichy Sankaran (Canada) 92-102 Saugita Lakshana Prachina Paddhati 7. S. Parthasarathy & P. K. Rajagopa/a Iyer 103-124 Indian Music on the March 7. S. -

N.G.M. College (Autonomous) Pollachi- 642 001

SHANLAX INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ARTS, SCIENCE AND HUMANITIES (A Peer-Reviewed, Refereed/Scholarly Quarterly Journal with Impact Factor) Vol.5 Special Issue 2 March, 2018 Impact Factor: 2.114 ISSN: 2321-788X UGC Approval No: 43960 International Conference on Contributions and Impacts of Intellectuals, Ideologists and Reformists towards Socio – Political Transformation in 20th Century Organised by DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY (HISTORIA-17) Diamond Jubilee Year September 2017 Dr.R.Muthukumaran Head, Department of History Dr.K.Mangayarkarasi Mr.R.Somasundaram Mr.G.Ramanathan Ms.C.Suma N.G.M. College (Autonomous) Pollachi- 642 001 Dr.B.K.Krishnaraj Vanavarayar President NGM College The Department of History reaches yet another land mark in the history of NGM College by organizing International Conference on “Contributions and Impacts of Intellectuals, Ideologists and Reformists towards Socio-political Transformation in 20th century”. The objective of this conference is to give a glimpse of socio-political reformers who fought against social stagnation without spreading hatred. Their models have repeatedly succeeded and they have been able to create a perceptible change in the mindset of the people who were wedded to casteism. History is a great treat into the past. It let us live in an era where we are at present. It helps us to relate to people who influenced the shape of the present day. It enables us to understand how the world worked then and how it works now. It provides us with the frame work of knowledge that we need to build our entire lives. We can learn how things have changed ever since and they are the personalities that helped to change the scenario. -

Unclaimed Dividend 2011

THE KARUR VYSYA BANK LIMITED, REGD. CENTRAL OFFICE: ERODE ROAD, KARUR 639002 [CIN No: L65110TN1916PLC001295] List of Unpaid dividend 2011‐12 transferred to IEPF Sl No Folio/ Demat ID SHARES STATUS PREFIX INITLS NAME AD1 AD2 AD3 AD4 PINCOD NETDIV DWNO 1 A00015 35 1 ALAGARSAMI CHETTIAR A S C/O G S A MOHAN DOSS 173/10 BIG BAZAR STREET CUMBUM-626 516 626516 490.00 1216730 2 A00054 420 1 ANASUYA K R 25 RAJAJI STREET KARUR 639001 5,880.00 1200477 3 A00057 134 1 ANBU SUBBIAH R 4 GANDHI NAGAR IST CROSS KARUR 639001 1,876.00 1200170 4 A00122 1142 1 ARJUNA BAI 68 BAZAAR STREET KEMPANAICKENPALAYAM VIA D G PUDUR ERODE R M S 638503 15,988.00 1200133 5 A00144 33 1 ALAMELU N 33 SOUTH CAR STREET PALANI 624 601 ANNA DISTRICT 624601 462.00 1200478 6 A00263 112 1 ARUMUGAM K 1 DAMASCUS ROAD NEW FAIRLANDS SALEM-636 016 636016 1,568.00 1218678 7 A00329 604 1 ALAMELU R 80 CAR STREET KARUR 639001 8,456.00 1201862 8 A00344 11 1 AMSA SEKHARAN S 58 I CROSS THILLAIPURAM NAMAKKAL 637001 154.00 1219168 9 A00416 9 1 ANNAPOORANI S W/O SURESH KUMAR, OFFICER THE KARUR VYSYA BANK LTD 45-46, CAR STREET SALEM 636001 126.00 1217742 10 A00428 100 1 ANUSUYA S 275 CHINNA KADAI STREET, SALEM 636001 1,400.00 1217743 11 A00435 33 1 ANUSUYA P 14 PULIYUR SECOND LANE KODAMBAKKAM MADRAS 600 024 600024 462.00 1200479 12 A00454 22 1 ARUMUGAM T 77 K V B NAGAR KARUR 2 639002 308.00 1200172 13 A00457 56 1 ARUNA B NO.9/11, M.M.INDUSTRIAL ROAD 7TH BLOCK, JAYANAGAR WEST YEDIYUR BANGALORE 560082 784.00 1210846 14 A00463 22 1 ASAITHAMBI K 22-C RATHINAM STREET KARUR-639001 639001 308.00 1201866 -

Permanent Mission of India to the United Nations New York

PERMANENT MISSION OF INDIA TO THE UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK BRIEF ON INDIA AND UNITED NATIONS India’s deepening engagement with the United Nations is based on its steadfast commitment to multilateralism and dialogue as the key for achieving shared goals and addressing common challenges faced by the global community including those related to peace building and peacekeeping, sustainable development, poverty eradication, environment, climate change, terrorism, disarmament, human rights, health and pandemics, migration, cyber security, space and frontier technologies like Artificial Intelligence, comprehensive reform of the United Nations, including the reform of the Security Council, among others. Picture Above: A. Ramaswami Mudaliar, supply member of the Governor General’s executive council and leader of the delegation from India, signing the UN Charter at a ceremony held at the Veterans’ War Memorial Building in San Francisco on June 26, 1945. Source: UN Photo/Rosenberg India was among the select members of the United Nations that signed the Declaration by United Nations at Washington on 1 January 1942. India also participated in the historic UN Conference of International Organization at San Francisco from 25 April to 26 June 1945. As a founding member of the United Nations, India strongly supports the purposes and principles of the UN and has made significant contributions to implementing the goals of the Charter, and the evolution of the UN’s specialized programmes and agencies. India strongly believes that the United Nations and the norms of international relations that it has fostered remain the most efficacious means for tackling today's global challenges. India is steadfast in its efforts to work with the committee of Nations in the spirit of multilateralism to achieve comprehensive and equitable solutions to all problems facing us including development and poverty eradication, climate change, terrorism, piracy, disarmament, peace building and peacekeeping, human rights. -

Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e-form IEPF-2 CIN/BCIN L24110MH1956PLC010806 Prefill Company/Bank Name CLARIANT CHEMICALS (INDIA) LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 09-AUG-2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 3803100.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id-Client Id- Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Account Number transferred (DD-MON-YYYY) THOLUR P O PARAPPUR DIST CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J DANIEL AJJOHN INDIA Kerala 680552 5932.50 02-Oct-2019 TRICHUR KERALA TRICHUR 3572 unpaid dividend INDAS SECURITIES LIMITED 101 CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A J SEBASTIAN AVJOSEPH PIONEER TOWERS MARINE DRIVE INDIA Kerala 682031 192.50 02-Oct-2019 3813 unpaid dividend COCHIN ERNAKULAM RAMACHANDRA 23/10 GANGADHARA CHETTY CLAR000000000A00 Amount for unclaimed and A K ACCHANNA INDIA Karnataka 560042 3500.00 02-Oct-2019 PRABHU -

Otto Koenigsberger and Tropical Architecture, from Princely Mysore to Post-Colonial London

A Pre-history of Green Architecture: Otto Koenigsberger and Tropical Architecture, from Princely Mysore to Post-colonial London By Vandana Baweja A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Architecture) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Robert L. Fishman, Chair Assistant Professor Andrew H. Herscher Assistant Professor Fernando Luiz Lara Assistant Professor Christi Ann Merrill Acknowledgements I would like to thank Robert Fishman, my advisor at the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, for his enormous support, guidance, and mentorship. I could not have hoped to work with a better advisor than Robert Fishman, for whom I have tremendous respect as a scholar and teacher. I hope I can be as wonderful and generous a mentor and teacher to my students as Professor Fishman has been to me. I’ve also received outstanding support from other faculty at the University of Michigan. Many thanks in particular to my dissertation committee, Andrew Herscher, Fernando Lara, and Christi Merrill, for their feedback, support, and advice. Christi Merrill has been a particularly supportive mentor and a wonderful friend whose criticism and advice enriched this dissertation tremendously. Christi’s exemplar mentoring skills have informed my pedagogical thinking and the kind of teacher I hope to be. David Scobey, who served on my exam committee, introduced me to a wonderful set of readings on architecture and nationalism. I owe him a great debt of gratitude for mentoring me through the preliminary exams. Thanks to Lydia Soo for offering two great doctoral colloquia in our department, the first of which helped me write my dissertation proposal and the second of which provided a great support group for finishing my dissertation chapters. -

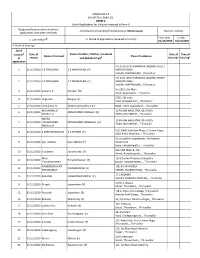

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Maduravoyal Revision identy applicaons have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Husband Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon NO 27/A, DEVI NARAYANA LAKSHMI STREET 1 01/12/2020 C E PRAKASAN C E NARAYANAN (F) MARUTHI RAM NAGAR, AYAPPAKKAM, , Thiruvallur NO 27/A, DEVI NARAYANA LAKSHMI STREET 2 01/12/2020 C E PRAKASAN C E NARAYANAN (F) MARUTHI RAM NAGAR, AYAPPAKKAM, , Thiruvallur No 2319, 5th Main 3 01/12/2020 Sumathi R Ramesh (H) Road, Ayapakkam, , Thiruvallur 2785, 5th main 4 01/12/2020 Jaiganesh Rangan (F) road, Ayyappakkam, , Thiruvallur 5 01/12/2020 Hemalatha D Dhatshinamoorthy K (H) 8640, TNHB, Ayapakkam, , Thiruvallur MOHAMMED 10 FA JAIN NAKSHTRA, 86 UNION 6 01/12/2020 MOHAMMED NORULLA (F) NASRULLA ROAD, NOLAMBUR, , Thiruvallur HAJIRA 10 FA JAIN NAKSHTRA, 86 UNION 7 01/12/2020 MOHAMMED MOHAMMED NASRULLA (H) ROAD, NOLAMBUR, , Thiruvallur NASRULLA C16, DABC Gokulam Phase 3, Sriram Nagar 8 01/12/2020 S SURIYAKRISHNAN K S SATHISH (F) Main Road, Nolambur, , Thiruvallur 42 sri Lakshmi apartments, 3rd Avenue 9 01/12/2020 sijo mathew biju mathew (F) millennium town, adayalampau, , Thiruvallur 312 VNR Milford, 7th 10 01/12/2020 Sundaram savarimuthu (F) Street, -

Salt Satyagraha the Watershed

I VOLUME VI Salt Satyagraha The Watershed SUSHILA NAYAR NAVAJIVAN PUBLISHING HOUSE AHMEDABAD-380014 MAHATMA GANDHI Volume VI SALT SATYAGRAHA THE WATERSHED By SUSHILA NAYAR First Edition: October 1995 NAVAJIVAN PUBLISHING HOUSE AHMEDABAD 380014 MAHATMA GANDHI– Vol. VI | www.mkgandhi.org The Salt Satyagraha in the north and the south, in the east and the west of India was truly a watershed of India's history. The British rulers scoffed at the very idea of the Salt March. A favourite saying in the barracks was: "Let them make all the salt they want and eat it too. The Empire will not move an inch." But as the Salt Satyagraha movement reached every town and village and millions of people rose in open rebellion, the Empire began to shake. Gandhi stood like a giant in command of the political storm. It was not however only a political storm. It was a moral and cultural storm that rose from the inmost depths of the soul of India. The power of non-violence came like a great sunrise of history. ... It was clear as crystal that British rule must give way before the rising tide of the will of the people. For me and perhaps for innumerable others also this was at the same time the discovery of Gandhi and our determination to follow him whatever the cost. (Continued on back flap) MAHATMA GANDHI– Vol. VI | www.mkgandhi.org By Pyarelal The Epic Fast Status of Indian Princes A Pilgrimage for Peace A Nation-Builder at Work Gandhian Techniques in the Modern World Mahatma Gandhi -The Last Phase (Vol. -

Current Affairs

CURRENT AFFAIRS (May,2020) NATIONAL NEWS ‘Year of Awareness on Science & Health (YASH)’ • It is launched by National Council for Science & Technology Communication (NCSTC), Department of Science & Technology (DST) . • The programme, with a focus on COVID-19, is an endeavour to disseminate information about best practices which will be vital to curbing the transmission of the virus and its management ‘ATULYA ’ • Defence Institute of Advanced Technology, Pune, a deemed university supported by Defence Research and Development Organisation has developed a microwave steriliser named as ‘ATULYA’ to disintegrate (COVID-19) Geographical Indication (GI) tag Manipur black rice, popularly known as ‘Chakhao’ by the locals, has bagged the Geographical Indication (GI) tag ‘Terracotta’ products made from the special soil found in Bhathat area of Uttar Pradesh Gorakhpur district is given Geographical Indication (GI) tag. Kovilpatti kadalai mittai -peanut candy from the southern part of Tamil Nadu -- was granted the Geographical Indication (GI) tag Kisan Sabha App • Kisan Sabha App developed by CSIR-Central Road Research Institute (CSIR-CRRI), New Delhi to connect farmers to supply chain and freight transportation management system. Founded- 26th Sept,1942 Founders- Shanti Swaroop Bhatnagar Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar Kashmir saffron • It is given Geographical Indication (GI) tag status. • It is mainly grown in Karewa soil in Jammu and Kashmir. • Kashmir saffron is the only one in the world grown at an altitude of 1600 meters • Iran is the largest Saffron producer in world. India's position in Scientific Research India occupies 3rd rank in terms of India is placed 3rd among number of PhDs awarded in countries in scientific Science and Engineering (S&E) publication. -

00 Copertina DEP N.37 2018

Numero 37 – Luglio 2018 Numero monografico Issue 37 – July 2018 Monographic Issue Stronger than Men. Women who worked with Gandhi and struggled for women’s rights Editor: Chiara Corazza ISSN: 1824-4483 DEP 37 Numero monografico Indice Introduzione , Chiara Corazza p. 1 Introduction p. 5 Ricerche Geraldine Forbes, Gandhi’s Debt to Women and Women’s Debt to Gandhi p. 8 Julie Laut, "The Woman Who Swayed America": Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, 1945 p. 26 Chiara Corazza, Dreams of a Poetess. A Subaltern Study of Sarojini Naidu’s Poetry and Political Thought p. 48 Thomas Weber, Gandhi e le donne occidentali, traduzione di Serena Tiepolato p. 70 Bidisha Mallik, Sarala Behn: The Silent Crusader p. 83 Sharon MacDonald, “The Other West”: Gandhian Quaker, Marjorie Sykes (1905–1995) p. 117 Holger Terp, Ellen Hørup and Other Gandhian Women in Denmark. p. 135 Documenti Sarala Behn, In the Mountains p. 151 Sujata Patel, Costruzione e ricostruzione della donna in Gandhi, traduzione di Sara De Vido e Lorenzo Canonico p. 161 Testimonianze Arun Gandhi, Kastur, Wife of Mahatma Gandhi p. 173 Radha Behn Bhatt, Personal Reflections p. 177 Strumenti di ricerca Suggerimenti bibliografici , a cura di Chiara Corazza p. 180 Recensioni, interventi, resoconti Thomas Weber, Going Native. Gandhi’s Relationship with Western Women (Chiara Corazza) p. 183 Sital Kalantry , Women’s human rights and migration. Sex-selective abortion laws in the US and India (Sara De Vido) p. 185 George A. James, Ecology is Permanent Economy: The Activism and Environmental Philosophy of Sunderlal Bahuguna (Bidisha Mallik) p. 189 Anita Anand, Sophia: Princess, Suffragette, Revolutionary (Sharon MacDonald) p. -

Foreign Policy Review

` 2016 Foreign Policy Review Annual Report on the Developments in the Field of Foreign Affairs Indian Council of World Affairs Sapru House, Barakhamba Road New Delhi-110070 www. icwa.in 1/1/2016 Foreign Policy Review – 2016 Foreign Policy Review 2016 Annual Report on the Developments in the Field of Foreign Affairs Prepared by Research Faculty Indian Council of World Affairs New Delhi 1 Foreign Policy Review – 2016 The Indian Council of World Affairs (ICWA) is India’s oldest foreign policy Think Tank, specializing in foreign and security policy issues. It was established before the independence of India in 1943 by a group of eminent intellectuals under the inspiration of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister. The Indian Council of World Affairs has been declared an “institution of national importance” by an Act of Parliament in 2001. The Council conducts policy research through its in-house faculty as well as external experts. It regularly organizes an array of intellectual activities including conferences, seminars, round table discussions, lectures and publication. It maintains a landmark and well established library, website and a journal named ‘India Quarterly’. It is engaged in raising public awareness about India’s role in international affairs and offers to the Government and civil society policy models and strategies, and serves as a platform for multi track dialogues and interaction with other foreign Think Tanks 2 Foreign Policy Review – 2016 Contents Chapter Page No. 1. South Asia 7 1.1. Afghanistan 7 1.2. Bangladesh 10 1.3. Nepal 11 1.4. Pakistan 15 1.5. Sri Lanka 17 2.