Ocean Currents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Ocean Observing System

The Global Ocean Observing System Dr Vladimir Ryabinin Executive Secretary of Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission; Assistant Director-General, UNESCO ICP-18 UN, New York 17.05.2017 IOC: Global Ocean Observing System IOC: Tsunami Warning System 1965- Pacific 2005- Indian Ocean Caribbean NE Atlantic & Mediterranean - Ocean Obs’99 - initiated global ocean climate observations - Ocean Obs’09 - initiated Framework for Ocean Observing - Ocean Obs’19 will focus on strengthening the linkages between the observing systems and the societal benefit areas where the knowledge of the oceanic environment is particularly essential (Hawaii, USA, September 2019) post-OO’09 Working Group A value chain Innovation, observations, data management, forecasts / science & assessment, societal benefit Adapted from G7 Think Piece on Ocean Observations GOOS Program Structure Ocean observations for societal benefit Climate, services, ocean health IOC: Global Ocean Observing System Driven by requirements, negotiated with feasibility Essential Ocean Variables Towards sustained system: requirements, observations, data management Readiness Mature Pilot Attributes: Products of the global ocean observing system are well understood, documented, consistently available, and Concept of societal benefit. Attributes: Planning, negotiating, testing, and approval within appropriate local, regional, global arenas. Attributes: Peer review of ideas and studies at science, engineering, and data management community level. EOVs and readiness level CONCEPT PILOT MATURE *also ECV -

Ocean Currents and the Pacific Garbage Patch

ocean currents and the Pacific Garbage Patch photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography The image above shows a net tow sample from the Pacific Garbage Patch. The sample contains small fish and many small pieces of plastic. The Garbage Patch is primarily composed of this small plastic “confetti” suspended throughout the surface water of the North Pacific Gyre, and is not a island of trash as suggested by some media outlets. The region where the trash converges in the center of the North Pacific Gyre, in a region where surface currents are weak and convergent, thus concentrating large amounts of trash in an area estimated to be close to the size of Texas. With this slide I often show a video clip about the Garbage Patch. Although the links may change, here is one from ABC that I’ve used several times: www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFMW8srq0Qk this video is a bit over the top but it gets the point across. There is additional information from Scripps Institution of Oceanography SEAPLEX experiment: http://sio.ucsd.edu/Expeditions/Seaplex/ and several videos on youtube.com by searching the phrase “SEAPLEX” Pacific garbage patch tiny plastic bits • the worlds largest dump? • filled with tiny plastic “confetti” large plastic debris from the garbage patch photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography little jellyfish photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography These are some of the things you find in the Garbage Patch. The large pieces of plastic, such as bottles, breakdown into tiny particles. Sometimes animals get caught in large pieces of floating trash: photo: NOAA photo: NOAA photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography How do plants and animals interact with small small pieces of plastic? fish larvae growing on plastic Trash in the ocean can cause various problems for the organisms that live there. -

Atlas of the Mediterranean Seamounts and Seamount-Like Structures

Atlas of the Mediterranean Seamounts and Seamount-like Structures ULISSE 44 N JANUA S.LUCIA SPINOLA OCCHIALI ARAGÓ CALYPSO HILLS 42 CIALDI FELIBRES HILLS 42 TIBERINO ETRUSCHI LA RENAIXENÇA HILLS ALBANO MONTURIOL S.FELIÙ SMS DAUNO VERCELLI SALVÁ BRUTUS SPARTACUS CASSINIS EBRO BARONIE-K MARUSSI SECCHI-ADRIANO FARFALLE ALBATROS-CICERONE CRESQUES BERTRAN SELLI VENUS MORROT DE LA CIUTADELLA GORTANI SELE MONTE DELLA RONDINE TACITO SÓLLER ALABE DE MARCHI SIRENE SARDINIA D’ANCONA FLAVIO GIOIA AMENDOLARA 40 SALLUSTIO 40 MAGNAGHI POSEIDONE ROSSANO APHRODITI VAVILOV TIBULLO DIAMANTE MORROT CORNAGLIA V.EMANUELE CARIATI DE SA DRAGONERA MAJOR ISSEL PALINURO-STRABO OVIDIO VILADESTERS CATULLO GLAVKI ORAZIO MARSILI-PLINIO GLABRO ENOTRIO MANSEL JOHNSTON STONY SPONGE QUIRRA ENEA TITO LIVIO VIRGILIO ALCIONE AUGUSTO SES OLIVES GARIBALDI-GLAUCO LAMETINO 1 BROUKER JAUME 1 CORNACYA LAMETINO 2 COLOM TRAIANO LUCREZIO STOKES XABIA-IBIZA VESPASIANO LITERI SINAYA VALLSECA SISIFO EMILE BAUDOT GIULIO CESARE-CAESAR DREPANO ENARETE CASONI FONTSERÈ ICHNUSA IRA NAVTILOS CABO DE LA NAO AUSIÀS MARCH ANCHISE BELL GUYOT POMPEO PROMETEO MARTORELL ACESTE-TIBERIO EOLO FORMENTERA SOLUNTO ALKYONI FERRER SCUSO SAN VITO LOS MARTINES ALÍ BEI FINALE DON JUAN RESGUI RIBA SENTINELLE (SKERKI) BALIKÇI EL38 PLANAZO BIDDLECOMBE SILVIA 38 PLIS PLAS KEITH SECO DE PALOS ESTAFETTE HECATE ADVENTURE TALBOT TETIDE 170 km ÁGUILAS GALATEA PANTELLERIA ANFITRITE EMPEDOCLE PINNE ANTEO 2 KHAYR-AL-DIN CIMOTOE ANTEO 3 ABUBACER FOERSTNER NAMELESS PNT. E MADREPORE ANTEO 1 AVENZOAR PNT. CB CHELLA CABO DE GATA ANGELINA ALFEO SABINAR PNT. SW AVEMPACE-ALGARROBO MAIMONIDES RIDGE BANNOCK KOLUMBO DJIBOUTI-HERRADURA POLLUX BILIM ADRA-AVERROES MAIMONIDES BIRSA PNT. SE HERRADURA-DJIBOUTI LINOSA III AL-MANSOUR A EL SEGOVIANO DJIBOUTI VILLE ALBORÁN LINOSA I LINOSA II HÉSPERIDES HÉRCULES EL IDRISSI YUSUF KARPAS CATIFAS-W. -

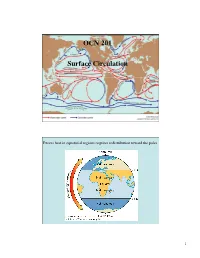

Surface Circulation2016

OCN 201 Surface Circulation Excess heat in equatorial regions requires redistribution toward the poles 1 In the Northern hemisphere, Coriolis force deflects movement to the right In the Southern hemisphere, Coriolis force deflects movement to the left Combination of atmospheric cells and Coriolis force yield the wind belts Wind belts drive ocean circulation 2 Surface circulation is one of the main transporters of “excess” heat from the tropics to northern latitudes Gulf Stream http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Newsroom/NewImages/Images/gulf_stream_modis_lrg.gif 3 How fast ( in miles per hour) do you think western boundary currents like the Gulf Stream are? A 1 B 2 C 4 D 8 E More! 4 mph = C Path of ocean currents affects agriculture and habitability of regions ~62 ˚N Mean Jan Faeroe temp 40 ˚F Islands ~61˚N Mean Jan Anchorage temp 13˚F Alaska 4 Average surface water temperature (N hemisphere winter) Surface currents are driven by winds, not thermohaline processes 5 Surface currents are shallow, in the upper few hundred metres of the ocean Clockwise gyres in North Atlantic and North Pacific Anti-clockwise gyres in South Atlantic and South Pacific How long do you think it takes for a trip around the North Pacific gyre? A 6 months B 1 year C 10 years D 20 years E 50 years D= ~ 20 years 6 Maximum in surface water salinity shows the gyres excess evaporation over precipitation results in higher surface water salinity Gyres are underneath, and driven by, the bands of Trade Winds and Westerlies 7 Which wind belt is Hawaii in? A Westerlies B Trade -

Ocean-Climate.Org

ocean-climate.org THE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN OCEAN AND CLIMATE 8 fact sheets WITH THE HELP OF: Authors: Corinne Bussi-Copin, Xavier Capet, Bertrand Delorme, Didier Gascuel, Clara Grillet, Michel Hignette, Hélène Lecornu, Nadine Le Bris and Fabrice Messal Coordination: Nicole Aussedat, Xavier Bougeard, Corinne Bussi-Copin, Louise Ras and Julien Voyé Infographics: Xavier Bougeard and Elsa Godet Graphic design: Elsa Godet CITATION OCEAN AND CLIMATE, 2016 – Fact sheets, Second Edition. First tome here: www.ocean-climate.org With the support of: ocean-climate.org HOW DOES THE OCEAN WORK? OCEAN CIRCULATION..............................………….....………................................……………….P.4 THE OCEAN, AN INDICATOR OF CLIMATE CHANGE...............................................…………….P.6 SEA LEVEL: 300 YEARS OF OBSERVATION.....................……….................................…………….P.8 The definition of words starred with an asterisk can be found in the OCP little dictionnary section, on the last page of this document. 3 ocean-climate.org (1/2) OCEAN CIRCULATION Ocean circulation is a key regulator of climate by storing and transporting heat, carbon, nutrients and freshwater all around the world . Complex and diverse mechanisms interact with one another to produce this circulation and define its properties. Ocean circulation can be conceptually divided into two Oceanic circulation is very sensitive to the global freshwater main components: a fast and energetic wind-driven flux. This flux can be described as the difference between surface circulation, and a slow and large density-driven [Evaporation + Sea Ice Formation], which enhances circulation which dominates the deep sea. salinity, and [Precipitation + Runoff + Ice melt], which decreases salinity. Global warming will undoubtedly lead Wind-driven circulation is by far the most dynamic. to more ice melting in the poles and thus larger additions Blowing wind produces currents at the surface of the of freshwaters in the ocean at high latitudes. -

Reading Handout: the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Reading Handout: The Great Pacific Garbage Patch The world’s oceans are connected by a complex network of water and wind currents, which combine to form gyres. The movement of wind and water in a gyre form large, slowly rotating whirlpools. The North Pacific Gyre is an area of the ocean between the continents of Asia and North America, and its whirlpool-like effect has pulled in pollution from around the world, forming the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is a massive accumulation of trash, large and small, in the North Pacific Gyre. {It is like a giant landfill floating in the ocean.} It is a combination of the Western Pacific Garbage Patch, located east of Japan and west of Hawaii, and the Eastern Pacific Garbage Patch, which floats between Hawaii and California. The two are connected by a thin 6,000-mile long current called the Subtropical Convergence Zone, which is also home to a large amount of pollution. The Patch is huge! However it cannot be seen from space, or even an airplane, because it is mostly made up of microplastics floating in the water column. Microplastics are pieces of plastic trash that are smaller than 5mm. Microplastics form when larger plastics break down, or come directly from a manufacturer in the form of nurdles (small plastic pellets used to make other plastic products). Nurdles absorb a lot of toxins as they float in the ocean, and those toxins become concentrated. Researchers estimate that for every 6 pounds (2.72 kilograms) of plastic, there is 1 pound (0.45 kilograms) of plankton. -

Ocean Circulation and Climate: an Overview

ocean-climate.org Bertrand Delorme Ocean Circulation and Yassir Eddebbar and Climate: an Overview Ocean circulation plays a central role in regulating climate and supporting marine life by transporting heat, carbon, oxygen, and nutrients throughout the world’s ocean. As human-emitted greenhouse gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere, the Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) plays an increasingly important role in sequestering anthropogenic heat and carbon into the deep ocean, thus modulating the course of climate change. Anthropogenic warming, in turn, can influence global ocean circulation through enhancing ocean stratification by warming and freshening the high latitude upper oceans, rendering it an integral part in understanding and predicting climate over the 21st century. The interactions between the MOC and climate are poorly understood and underscore the need for enhanced observations, improved process understanding, and proper model representation of ocean circulation on several spatial and temporal scales. The ocean is in perpetual motion. Through its DRIVING MECHANISMS transport of heat, carbon, plankton, nutrients, and oxygen around the world, ocean circulation regulates Global ocean circulation can be divided into global climate and maintains primary productivity and two major components: i) the fast, wind-driven, marine ecosystems, with widespread implications upper ocean circulation, and ii) the slow, deep for global fisheries, tourism, and the shipping ocean circulation. These two components act industry. Surface and subsurface currents, upwelling, simultaneously to drive the MOC, the movement of downwelling, surface and internal waves, mixing, seawater across basins and depths. eddies, convection, and several other forms of motion act jointly to shape the observed circulation As the name suggests, the wind-driven circulation is of the world’s ocean. -

6 Ocean Currents 5 Gyres Curriculum

Lesson Six: Surface Ocean Currents Which factors in the earth system create gyres? Why does pollution collect in the gyres? Objective: Develop a model that shows how patterns in atmospheric and ocean currents create gyres, and explain why plastic pollution collects in them. Introduction: Gyres are circular, wind-driven ocean currents. Look at this map of the five main subtropical gyres, where the colors illustrate enormous areas of floating waste. These are places in the ocean that accumulate floating debris—in particular, plastic pollution. How do you think ocean gyres form? What patterns do you notice in terms of where the gyres are located in the ocean? The Earth is a system: a group of parts (or components) that all work together. The components of a system have different structures and functions, but if you take a component away, the system is affected. The system of the Earth is made up of four main subsystems: hydrosphere (water), atmosphere (air), geosphere (land), and biosphere (organisms). The ocean is part of our planet’s hydrosphere, but it is also its own system. Which components of the Earth system do you think create gyres, and why would pollution collect in them? Activity 1 Gyre Model: How do you think patterns in ocean currents create gyres and cause pollution to collect in the gyres? Use labels and arrows to answer this question. Keep your diagram very basic; we will explore this question more in depth as we go through each part of the lesson and you will be able to revise it. www.5gyres.org 2 Activity 2 How Do Gyres Form? A gyre is a circulating system of ocean boundary currents powered by the uneven heating of air masses and the shape of the Earth’s coastlines. -

Chapter 51. Biological Communities on Seamounts and Other Submarine Features Potentially Threatened by Disturbance

Chapter 51. Biological Communities on Seamounts and Other Submarine Features Potentially Threatened by Disturbance Contributors: J. Anthony Koslow, Peter Auster, Odd Aksel Bergstad, J. Murray Roberts, Alex Rogers, Michael Vecchione, Peter Harris, Jake Rice, Patricio Bernal (Co-Lead members) 1. Physical, chemical, and ecological characteristics 1.1 Seamounts Seamounts are predominantly submerged volcanoes, mostly extinct, rising hundreds to thousands of metres above the surrounding seafloor. Some also arise through tectonic uplift. The conventional geological definition includes only features greater than 1000 m in height, with the term “knoll” often used to refer to features 100 – 1000 m in height (Yesson et al., 2011). However, seamounts and knolls do not appear to differ much ecologically, and human activity, such as fishing, focuses on both. We therefore include here all such features with heights > 100 m. Only 6.5 per cent of the deep seafloor has been mapped, so the global number of seamounts must be estimated, usually from a combination of satellite altimetry and multibeam data as well as extrapolation based on size-frequency relationships of seamounts for smaller features. Estimates have varied widely as a result of differences in methodologies as well as changes in the resolution of data. Yesson et al. (2011) identified 33,452 seamount and guyot features > 1000 m in height and 138,412 knolls (100 – 1000 m), whereas Harris et al. (2014) identified 10,234 seamount and guyot features, based on a stricter definition that restricted seamounts to conical forms. Estimates of total abundance range to >100,000 seamounts and to 25 million for features > 100 m in height (Smith 1991; Wessel et al., 2010). -

Mid-Depth Calcareous Contourites in the Latest Cretaceous of Caravaca (Subbetic Zone, SE Spain)

Mid-depth calcareous contourites in the latest Cretaceous of Caravaca (Subbetic Zone, SE Spain). Origin and palaeohydrological significance Javier Martin-Chivelet*, Maria Antonia Fregenal-Martinez, Beatriz Chac6n Departamento de 8stratigrajia. institute de Geologia Economica (CSiC-UCM). Facultad de Ciencias Geologicas. Universidad Complutense. 28040 Madrid, Spain Abstract Deep marine carbonates of Late Campanian to Early Maastrichtian age that crop out in the Subbetic Zone near Caravaca (SE Spain) contain a thick succession of dm-scale levels of calcareous contourites, alternating with fine-grained pelagitesl hemipelagites. These contourites, characterised by an abundance and variety of traction structures, internal erosive surfaces and inverse and nOlmal grading at various scales, were interpreted as having been deposited under the influence of relatively deep ocean CUlTents. Based on these contourites, a new facies model is proposed. The subsurface currents that generated the contourites of Caravaca were probably related to the broad circumglobal, equatorial current system, the strongest oceanic feature of Cretaceous times. These deposits were formed in the mid-depth (200-600 m), hemipelagic environments at the ancient southern margin of Iberia. This palaeogeographic setting was susceptible to the effects of these currents because of its position close to the narrowest oceanic passage, through which the broad equatorial cun'ent system flowed in the westemmost area of the Tethys Seaway. Regional uplift, related to the onset of convergence between Iberia and Africa, probably favoured the generation of the contourites during the Late Campanian to the Early Maastrichtian. Keyword\': Contourites; Palaeoceanography; Late Cretaceous; Caravaca; Betics; SE Spain 1. Introduction aI., 1996; Stow and Faugeres, 1993, 1998; Stow and Mayall, 2000a; Shanmugam, 2000). -

Coastal Upwelling Revisited: Ekman, Bakun, and Improved 10.1029/2018JC014187 Upwelling Indices for the U.S

Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans RESEARCH ARTICLE Coastal Upwelling Revisited: Ekman, Bakun, and Improved 10.1029/2018JC014187 Upwelling Indices for the U.S. West Coast Key Points: Michael G. Jacox1,2 , Christopher A. Edwards3 , Elliott L. Hazen1 , and Steven J. Bograd1 • New upwelling indices are presented – for the U.S. West Coast (31 47°N) to 1NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center, Monterey, CA, USA, 2NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory, Boulder, CO, address shortcomings in historical 3 indices USA, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, USA • The Coastal Upwelling Transport Index (CUTI) estimates vertical volume transport (i.e., Abstract Coastal upwelling is responsible for thriving marine ecosystems and fisheries that are upwelling/downwelling) disproportionately productive relative to their surface area, particularly in the world’s major eastern • The Biologically Effective Upwelling ’ Transport Index (BEUTI) estimates boundary upwelling systems. Along oceanic eastern boundaries, equatorward wind stress and the Earth s vertical nitrate flux rotation combine to drive a near-surface layer of water offshore, a process called Ekman transport. Similarly, positive wind stress curl drives divergence in the surface Ekman layer and consequently upwelling from Supporting Information: below, a process known as Ekman suction. In both cases, displaced water is replaced by upwelling of relatively • Supporting Information S1 nutrient-rich water from below, which stimulates the growth of microscopic phytoplankton that form the base of the marine food web. Ekman theory is foundational and underlies the calculation of upwelling indices Correspondence to: such as the “Bakun Index” that are ubiquitous in eastern boundary upwelling system studies. While generally M. G. Jacox, fi [email protected] valuable rst-order descriptions, these indices and their underlying theory provide an incomplete picture of coastal upwelling. -

Ridge Migration, Asthenospheric Flow and the Origin of Magmatic Segmentation in the Global Mid-Ocean Ridge System Richard F

GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 31, L15605, doi:10.1029/2004GL020388, 2004 Ridge migration, asthenospheric flow and the origin of magmatic segmentation in the global mid-ocean ridge system Richard F. Katz, Marc Spiegelman, and Suzanne M. Carbotte Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, New York, USA Received 28 April 2004; accepted 7 July 2004; published 4 August 2004. [1] Global observations of mid-ocean ridge (MOR) [3] Previous authors have considered the possible effect bathymetry demonstrate an asymmetry in axial depth of ridge migration on MOR processes. A kinematic model across ridge offsets that is correlated with the direction of asthenospheric flow beneath a migrating ridge was used of ridge migration. Motivated by these observations, we by Davis and Karsten [1986] to explain the asymmetric have developed two-dimensional numerical models of distribution of seamounts about the Juan de Fuca ridge and asthenospheric flow and melting beneath a migrating MOR. by Schouten et al. [1987] to study the migration of non- The modification of the flow pattern produced by ridge transform offsets at spreading centers. Modeling studies migration leads to an asymmetry in melt production rates [Conder et al., 2002; Toomey et al., 2002] of the MELT on either side of the ridge. By coupling a simple parametric region of the EPR [Forsyth et al., 1998b] found the dynamic model of three dimensional melt focusing to our simulations, effect of ridge migration could produce an asymmetry in we generate predictions of axial depth differences across melt production, but not of the magnitude inferred from offsets in the MOR. These predictions are quantitatively across-ridge differences in P, S and Rayleigh wave veloc- consistent with the observed asymmetry.