Mysore and Coorg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

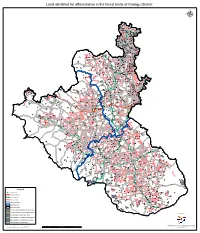

Land Identified for Afforestation in the Forest Limits of Kodagu District Μ

Land identified for afforestation in the forest limits of Kodagu District µ Hampapura Kesuru Santapura Doddakodi Malaganahalli Kasuru Mavinahalli Hosahalli Janardanahalli Nirgunda KallahalliKodlipet Mollepura Kattepura Nandipura Ramenahalli Ichalapura Ramenahalli Chikkakunda Agali Konginahalli Kattepura Mallahalli Doddakunda Basavanahalli Kudlu Besuru Nilavagilu Urugutti Lakham Kudluru Chikkabandara Bettiganahalli Korgallu Bemballur Hemmane Kiribilaha Talaguru Taluru Doddabilaha Avaredalu Lakkenahalle Siraha Hulukadu Kitturu Harohalli Toyahalli Managali Madare Bageri Dandhalli Hosahalli Bettadahalli Dundalli Mudaravalli Kujageri Kerehalli Hosapura Yedehalli Bellarhalli Kallahalli Sanivarsante Chikanahalli Huluse Gudugalale Sirangala Doddakolaturu Choudenahalli Hemmane Sidagalale Settiganahalli Doddahalli Appasethalli Gangavara Vaderapura Kyatanahalli Gopalpura Kysarahalli Bettadahalli Hittalkeri Nidta Menasa Modagadu Sigemarur Hunsekayihosahalli Mulur Ramenahalli Forest Quarters Mailatapura Mallalli Honnekopal Kurudavalli Nagur Amballi Hattihalli Badabanahalli Nandigunda Kodhalli Nagarahalli Kuti Kundahalli Heggula Bachalli Kanave Basavanahalli Harohalli Bidahalli Kumarhalli Santveri Heggademane Singanhalli Koralalhalli Basavanakoppa Hosagutti Kundahalli Inkalli Dinnehesahalli Tolur Shetthalli Hasahalli Jakhanalli Mangalur Nadenahalli Gaudahalli Malambi Sunti Ajjalli Bettadahalli Doddatolur Kugur Chikkara Santhalli Kogekodi Kantebasavanahalli Gejjihanakodu Chennapuri Alur Honnahalli Siddapura Kudigana Hirikara HitiagaddeKallahalli Sulimolate -

Proposed Date

First Name Father/Husba Address Country State PINCode Folio Number of Securities Amount Proposed Date of nd First Name Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF (DD- MON-YYYY) ZUBEENA MONEM NA XXX XXX XX INDIA Andhra Pradesh 999999 0000000000CEZ0018034 214.50 01-AUG-2013 ZUBEDA BEN GANDHI NA NAVA PARA NATHI BAI MASJID JAMNAGAR GUJARATINDIA Gujarat 361001 0000000000CEZ0018028 279.50 01-AUG-2013 ZUBEDA ASHRAF NA 44/315 MESTON ROAD KANPUR INDIA Uttar Pradesh 202001 0000000000CEZ0018027 214.50 01-AUG-2013 ZENI ABID KAGALWALA NA 95 NAVRANG PEDDAR ROAD BOMBAY INDIA Maharashtra 400026 0000000000CEZ0018020 104.00 01-AUG-2013 ZACHARIAH G PUNNACHALILNA THIRUVANKULAM PO ERNAKULAM DIST KERALA INDIA Kerala 682305 0000000000CEZ0018002 13.50 01-AUG-2013 YOGESH MANUBHAI DESAINA 42 G D AMBEKAR ROAD 202 INDIA PRINTING HOUSEINDIA WADALAMaharashtra BOMBAY 400031 0000000000CEY0018087 539.50 01-AUG-2013 YOGESH KAMANI NA PRAKASH NO 1 BLOCK NO 3 28 B G KHAR MARG BOMBAYINDIA Maharashtra 400006 0000000000CEY0018084 104.00 01-AUG-2013 YOGENDRA PRASAD NA C/O B N RAY LIC BR 2 PODHANSAR DHANBAD INDIA Jharkhand 826001 0000000000CEY0018069 104.00 01-AUG-2013 YERRAM GOPAL REDDY NA PLOT NO 34 H NO 27-64/5/2/1/A SRI KRISHNA NAGARINDIA - WESTAndhra POST- Pradesh R K PURAM 500056SECUNDRABAD0000000000CEY0018061 104.00 01-AUG-2013 YELAMANCHILI SWARNALATHANA 8-3-214/13 SRINIVAS NAGAR WEST VENGAL RAO INDIANAGAR POSTAndhra HYDERABAD Pradesh 500038 0000000000CEY0018060 104.00 01-AUG-2013 YASHWIN T KHATTAN NA C/O INDUSTO PLAST 138 ADHYARA IND ESTATE SUNINDIA MILL MaharashtraCOMPOUND LOWR PAREL400013 -

PTO, Madikeri-RTI 4(1)

Office of the Profession Tax Officer, Madikeri, Kodagu District, Information furnished u/s 4(1)(a) of the RTI Act 2005 (Note: NA = Not Applicable) Record Maintenance Sl No File No RCN/ECN Trade Name Adress Subject Year of Date of Category Date on which Name of the Date on which Name of the Rack/ Bundle Year Year of Datet of Name of officer Name of the opening closing A B C D E file sent to official who has sent the file is received officer i/c of Almirah No No disposal destruction who has ordered officer who the file record room file to the in the record record room of the for destruction has destroyed record room room record of the record the record 1 2 2a 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11a 11b 11c 12 13 14 15 1 270 175370476 PAVITHRA BOPANNA - Profession Tax-EC 2010 NA C NA NA NA Dr.G.Viswanatha 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA 2 271 131369210 S.J.SANJAY - Profession Tax-EC 2010 NA C NA NA NA Dr.G.Viswanatha 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA 3 272 120373210 D.PRADEEP JAGANATH - Profession Tax-EC 2010 NA C NA NA NA Dr.G.Viswanatha 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA 4 273 110368813 ROHAN MASCARENHAS - Profession Tax-EC 2010 NA C NA NA NA Dr.G.Viswanatha 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA 5 274 153369940 EARAPPA B.S. - Profession Tax-EC 2010 NA C NA NA NA Dr.G.Viswanatha 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA 6 275 155369539 NARAYANA C - Profession Tax-EC 2010 NA C NA NA NA Dr.G.Viswanatha 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA 7 276 192369541 DOMBAIAH HB - Profession Tax-EC 2010 NA C NA NA NA Dr.G.Viswanatha 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA 8 277 128374807 C.K.SHIV SOMANNA - Profession Tax-EC 2010 NA C NA NA NA Dr.G.Viswanatha 1 2 NA NA NA NA NA 9 278 152375427 B.A. -

Police Station List

PS CODE POLOCE STATION NAME ADDRESS DIST CODEDIST NAME TK CODETALUKA NAME 1 YESHWANTHPUR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 2 JALAHALLI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 3 RMC YARD PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 4 PEENYA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 5 GANGAMMAGUDI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 6 SOLADEVANAHALLI PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 7 MALLESWARAM PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 8 SRIRAMPURAM PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 9 RAJAJINAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 10 MAHALAXMILAYOUT PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 11 SUBRAMANYANAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 12 RAJAGOPALNAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 13 NANDINI LAYOUT PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 14 J C NAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 15 HEBBAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 16 R T NAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 17 YELAHANKA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 18 VIDYARANYAPURA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 19 SANJAYNAGAR PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 20 YELAHANKA NEWTOWN PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 1 Bangalore North 21 CENTRAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 22 CHAMARAJPET PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 23 VICTORIA HOSPITAL PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 24 SHANKARPURA PS BANGALORE 20 BANGALORE 2 Bangalore South 25 RPF MANDYA MANDYA 22 MANDYA 5 Mandya 26 HANUMANTHANAGAR PS BANGALORE -

Kodagu Updated F-Register As on 31-03-2019

F-Register as on 31-03-2019 Sl.No. PCBID Year of Name & Address Address Area/ Taluk District Name of the Type of Product Category Size Colour date of capital Present Applicabi Water Act Air Act Air Act HW HWM BM BMW Registrati Registrat Batte E- E- MS MS Rem Identifica of the of the Place/ Industrial Organisat No (L/M/S/ (R/O/G/ establish investme Working lity under (Validity) (Y/N) (Validity M (Validi W (Valid on under ion ry Waste Wast W W arks tion (YY- Organisations Organisat Ward Estates/ ion/ (XGN Micro) W) ment nt (in Status Water ) (Y/ ty) (Y/ ity) Plastic under (Y/N (Y/N) e (Y/ (Vali YY) ions No. areas Activity* category (DD/MM Lakhs) (O/C1/ Act N) N) rules plastic ) (Vali N) dity) (I/ M/ code) /YY) C2/Y)** (Y/N) (Y/N) rules dity) LB/HC/ (validity (8) H/L/CE/ date) (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (9) (10) (11) (12) (13) (14) (15) (16) (17) (18) (19) (20) (21) (22) (23) (24) (25) (26) (27) (28) (29) (30) (31) (32) (33) 1 2013-14 A.R. Coffee Curing Virajp Kodagu I Coffee curing, Small Green 13.65 O Y 31-12-2021 31-12- N Works, Halagunda et roasting and 2021 Village, Virajpet grinding 1572 30/11/1999 _ taluk, Coorg District. (industrial scale) 2 2013-14 Abrar Engineering Madik Kodagu I General Small White 3.5 O Y 31-12-2114 31-12- N Corporation, eri Engineering 2114 P.B.No.46, Plot Industries 14 25/9/2001 _ No.L4, Industrial (Excluding Estate, Madikeri, electroplating, 3 2013-14 Aimara Coffee Somw Kodagu KIADB I Coffee curing, Small Green 48 C1 Y Closed Closed N Curing Works, 1p, arpet Industrial roasting and Kiadb Industrial Area, grinding 1572 23/7/1999 _ Area, Kushalnagar, Kushalnagar (industrial scale) Virajpet taluk, 4 2013-14 Akshara Wood Virajp Kodagu I Saw mills Small Green 5 Y Y YTC YTC N Industries, No.89/11, et Mathoon Village, 11/7/2002 _ Virajpet taluk, Coorg. -

Kodagu District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18

Kodagu District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18 Kodagu District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18 Kodagu District map Message (Deputy Commissioner) Kodagu District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18 Index Content Page No. Abbreviation 1 Kodagu District Disaster Management Team 2-4 Chapter-1 INTRODUCTION 5-14 PART – A 1. DISTRICT PROFILE 1.1 Geography 1.2 Rainfall And Climate 1.3 Demography Of The Land 1.4 Kodagu District Administrative Setup 1.5 Socio Economic Profile Of The District 1.6.A. Agriculture 1.6.B. Geo Morphology Of Soil Types 1.6.C. Education 1.6.D. Tourism 1.6.E. Land Utilization Details 1.6.F. Infrastructure 1.6.G. Critical Infrastructures Of The District PART- B 15-18 1.7 Key Resources Of The Kodagu District 1.7a Details Of Rivers And Dams 1.7b Details Of Drinking Water 1.7c Flora And Fauna 1.8 Road Network 1.9 Details Of Media And Communications 1.10. Details of Power Generating Industries 1.11 Details Of Industries PART-C 19-26 1.12 Kodagu District Disaster Management Plan 1.12. A Scope Of The Kodagu District Disaster Management Plan: 1.12. B Kodagu - District Disaster Management Authority (DDMA):- 1.12.C. Laws And Statues 1.12.D Powers And Functions Of Kodagu District Authority 1.12.E The Plan development 1.13 Stake Holders And Their Responsibility 1.14 Kodagu ULBs And Their Support For Dm Plan 1.15. Formal Agreement (MOU) With Utility Agencies Kodagu District Disaster Management Plan 2017-18 1.16 How To Use The DDMP Plan 1.17 Approval Mechanism Of The DDMP – Authority For Implementation (State Level/District Level Orders) -

Large Scale Burning for a Threatened Ungulate in a Biodiversity Hotspot Is Detrimental for Grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Caelifera)

Biodiversity and Conservation https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-019-01816-6 ORIGINAL PAPER Large scale burning for a threatened ungulate in a biodiversity hotspot is detrimental for grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Caelifera) Dhaneesh Bhaskar1,2,3 · P. S. Easa1,2 · K. A. Sreejith1,2 · Josip Skejo3,4 · Axel Hochkirch3,5 Received: 9 January 2019 / Revised: 25 June 2019 / Accepted: 28 June 2019 © Springer Nature B.V. 2019 Abstract Habitat management strategies across the globe are often focusing on fagship species, such as large threatened mammals. This is also true for most protected areas of India, where large mammals such as the Tiger or Asian Elephant represent focal species of con- servation management, although a shift towards other species groups can be observed in recent times. Prescribed burning is a controversially debated method to manage open habi- tat types. This method is practised as a tool to manage the habitat of the endangered Nilgiri tahr, Nilgiritragus hylocrius (an endemic goat) at a large scale (50 ha grids) in Eraviku- lam National Park of the Western Ghats (Kerala, India). However, the impact of prescribed burning on other biota of this unique environment in a global biodiversity hotspot has not been studied. We compared the impact of large-scale prescribed burning on grasshopper abundances in Eravikulam National Park with small-scale burning in Parambikulam Tiger Reserve from 2015 to 2018, to assess the impact of the diferent fre management prac- tices of these reserves on this species-rich insect group. We observed a negative response of grasshoppers to burning of larger contiguous areas in terms of their recovery after fre events, whereas burning small patches in a mosaic pattern facilitated rapid recovery of grasshopper communities. -

Madikeri Bar Association : Madikeri Taluk : Madikeri District : Kodagu

3/17/2018 KARNATAKA STATE BAR COUNCIL, OLD KGID BUILDING, BENGALURU VOTER LIST POLING BOOTH/PLACE OF VOTING : MADIKERI BAR ASSOCIATION : MADIKERI TALUK : MADIKERI DISTRICT : KODAGU SL.NO. NAME SIGNATURE VASUDEVA N G MYS/40/60 1 S/O LATE N.R. GOPALAKEISHNA HILL ROAD TOWN MADIKERI KODAGU 571 201 ZAKARIYA P M MYS/200/68 S/O P.A. MOHIDEEN 2 NADAF MANZIL NAZEER COMPOUNG PRAKRITHI LAYOUT COLLEGE ROAD ` MADIKERI KODAGU 571 201 BOPAYA K W MYS/89/69 3 S/O LATE SRI K P UTHAIAH GOWRI STRRET MADIKERI KODAGU 571 201 VASUDEVA M C MYS/140/73 S/O M MCHENGAPPA 4 1ST FLOOR MATHEW BUILING LOKAYUKTA OFFICE GOWLI STREET MADIKERI KODAGU 571 201 1/35 3/17/2018 MACHAIAH B A MYS/200/74 5 S/O B M MACHAIAH VIL: KONAJAGERI PO: PARAVE MADIKERI KODAGU NEMIRAJ T S MYS/317/74 S/O THEKKADA MUTHANNA SUBBAIAH 6 GUNDU RAO BADAVANE 1ST BLOCK, B.M ROAD , KUSHALNAGAR MADIKERI KODAGU 571 234 KUTTAPPA K.A. KAR/192/76 S/O K M APPACHU 7 SEETHA VILLA ESTATE , BETTAGERE P.O. (VIA) COORG. MADIKERI KODAGU BALASUBRAMANYA K.P. KAR/334/76 8 S/O PARAMESHWARAYYA K (LATE) 'SIRI' BRAHMIN VALLEY MADIKERI KODAGU 571 201 GOPAL P.C. KAR/27/77 S/O CHINNAPPA P U (LATE) 9 CHARANDETTI VILLAGE, CHETTYMANI POST, BHAGAMANDALA HOBLI MADIKERI KODAGU 2/35 3/17/2018 GOPALAKRISHNA BHAT K. KAR/128/77 S/O LATE SRI K NARAYANA BHAT 10 SRI BHARADWAJ, CAUVERY LAYOUT, CONVENT JUNCTION MADIKERI KODAGU SUBBAIAH P.A. KAR/163/78 11 S/O LATE P.A.AIYAMMA MAN'S COMPOUND ROAD , AAKANKSHE MADIKERI KODAGU 571 201 UTHAPPA P.M. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

Payout Summary to RO RISC14 Blossom 9.7.14.Xlsx

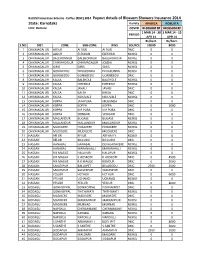

Rainfall Insurance Scheme -Coffee (RISC) 2014 Payout details of Blossom Showers Insurance 2014 State: Karnataka Variety ARABICA ROBUSTA Unit: Hectare COVER BLOSSOM RF BLOSSOM RF 1 MAR 14 - 30 1 MAR 14 - 15 PERIOD APR 14 APR 14 Rs/hect. Rs/hect. S.NO. DIST. ZONE SUB-ZONE RWS SOURCE 10000 8000 1 CHIKMAGALUR ALDUR ALDUR ALDUR DMC 0 0 2 CHIKMAGALUR ALDUR ELEKHAN ELEKHAN NCMSL 0 0 3 CHIKMAGALUR BALEHONNUR BALEHONNUR BALEHONNUR NCMSL 0 0 4 CHIKMAGALUR CHIKMAGALUR CHIKMAGALUR JOLDAL NCMSL 0 0 5 CHIKMAGALUR GIRIS GIRIS GIRIS NCMSL 0 0 6 CHIKMAGALUR GONIBEEDU DEVARUNDA DEVARUNDA NCMSL 0 0 7 CHIKMAGALUR GONIBEEDU GONIBEEDU GONIBEEDU DMC 0 0 8 CHIKMAGALUR KALSA BALEHOLE BALEHOLE NCMSL 0 0 9 CHIKMAGALUR KALSA HIREBYLE HIREBYLE NCMSL 0 0 10 CHIKMAGALUR KALSA JAVALI JAVALI DMC 0 0 11 CHIKMAGALUR KALSA KALSA KALSA DMC 0 0 12 CHIKMAGALUR KALSA NIDUVALE NIDUVALE NCMSL 0 0 13 CHIKMAGALUR KOPPA JAYAPURA MEGUNDA DMC 0 0 14 CHIKMAGALUR KOPPA KOPPA KOPPA DMC 0 2000 15 CHIKMAGALUR KOPPA N R PURA N R PURA DMC 0 0 16 CHIKMAGALUR KOPPA SRINGERI SRINGERI DMC 0 0 17 CHIKMAGALUR MALLANDUR BOGASE BOGASE NCMSL 0 0 18 CHIKMAGALUR MALLANDUR MALLANDUR MALLANDUR NCMSL 0 0 19 CHIKMAGALUR MUDIGERE HOSAKERE HOSAKERE NCMSL 0 0 20 CHIKMAGALUR MUDIGERE MUDIGERE MUDIGERE DMC 0 0 21 HASSAN BELUR BELUR AREHALLY NCMSL 0 0 22 HASSAN BELUR BICCODU BICCODU DMC 0 0 23 HASSAN HANABAL HANABAL DEVALADAKERE NCMSL 0 0 24 HASSAN HANABAL MARANHALLI MARANHALLI NCMSL 0 0 25 HASSAN R K MAGGE HALLIYUR HALLIYUR NCMSL 0 0 26 HASSAN R K MAGGE K HOSKOTE K HOSKOTE DMC 0 4500 27 HASSAN R K MAGGE R K -

Loan Phase III (1).Xlsx

Loan Crop Loan waived S.L No BANK NAME BRANCH CustomerName CustomerRelative Name RATIONCARD Type Amount in ( Rs ) 1 STATE BANK OF INDIA GONIKOPPAL VASU M P LATE M G PONNAPPA RGL VRP15125940 25000 2 UNION BANK OF INDIA SRIMANGALA MURALI P S 0 RGL VRP14109147 15026.72 3 UNION BANK OF INDIA SRIMANGALA POONACHA B M 0 RGL VRP15119431 25000 4 UNION BANK OF INDIA SRIMANGALA SHANTHI B M 0 RGL VRPR00112392 25000 5 UNION BANK OF INDIA SRIMANGALA MURALI P S 0 RGL VRP14109147 9973.28 6 UNION BANK OF INDIA SRIMANGALA T.C.APPAIAH 0 RGL VRP15104480 13830.97 7 UNION BANK OF INDIA SRIMANGALA SUBBAIAH K S 0 RGL VRPR00115706 25000 8 UNION BANK OF INDIA SRIMANGALA BADUMANDA T VIJAYA 0 RGL VRP15108898 25000 9 UNION BANK OF INDIA MADIKERI JANARDANA.P.A. 0 RGL mdkr00113345 25000 10 UNION BANK OF INDIA MADIKERI DHANANJAYA K M 0 RGL mdk14118212 25000 11 UNION BANK OF INDIA MADIKERI MADAPPA N M 0 RGL mdk16129998 25000 12 UNION BANK OF INDIA MADIKERI ANANDA C B 0 RGL mdkr00108127 25000 13 Indian Overseas Bank Napoklu, Chennarayapatna KUNDANDA M ABDULLA 0 RGL MDKR00103334 25000 14 Indian Overseas Bank Napoklu, Chennarayapatna SUBRAMANI T M 0 RGL MDK16113148 25000 15 Indian Overseas Bank Napoklu, Chennarayapatna POOVANNA K K 0 RGL MDKR00113277 6232.18 16 Indian Overseas Bank Napoklu, Chennarayapatna KURULI S MAYINE 0 RGL 180100117617 19097 17 Indian Overseas Bank Pollibetta MUTHANNA C A 0 RGL VRPR00105622 25000 18 Indian Overseas Bank Pollibetta M M VIVEK TATA COFFE 0 RGL MDKU00109817 25000 19 Indian Overseas Bank Madikeri PONAPPA 0 RGL SVPR00122390 25000 20 Indian