Ecotourism in a Small Caribbean Island: Lessons Learned for Economic Development and Nature Preservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Hotels and Motels ON-CAMPUS ACCOMODATIONS the FACULTY CLUB UC CAMPUS University of California Berkeley, Ca 94704-6050 510-540-5678

local hotels and motels ON-CAMPUS ACCOMODATIONS THE FACULTY CLUB UC CAMPUS University of California Berkeley, Ca 94704-6050 510-540-5678 www.berkeleyfacultyclub.com THE WOMEN’S FACULTY CLUB UC CAMPUS University of California Berkeley, Ca 94720-6055 510-642-4175 www.womensfacultyclub.com/ OFF-CAMPUS ACCOMODATIONS BANCROFT HOTEL 2680 Bancroft Way cal rentals Berkeley Ca 94704 (0.7 mi) 2610 Channing Way 510-549-1000 Berkeley, CA 94720-2272 www.bancrofthotel.com HOURS: BEAU SKY HOTEL Monday–Friday, 2520 Durant Avenue 10 a.m. – 4 p.m., excluding Berkeley, Ca 94704 (0.8 mi) official University holidays 510-540-7688 800-990-2328 WEB SITE: www.beausky.com calrentals.berkeley.edu BERKELEY CITY CLUB E-MAIL: 2315 Durant Ave [email protected] Berkeley, Ca 94704 (0.4 mi) 510-848-7800 PHONE: www.berkeleycityclub.com/ (510) 642-3644 BERKELEY LAB GUEST HOUSE One Cyclotron Road, Building 23 Berkeley, CA 94720 510 495-8000 berkeleylabguesthouse.berkeley.edu CLAREMONT RESORT & SPA 41 Tunnel Road Berkeley, Ca 94705 (2.8 mi) 510-843-3000 800-551-7266 www.claremontresort.com COURTYARD MARRIOTT 5555 Shellmound Street Emeryville, Ca 94608 (4 mi) 510-652-8777 800-828-4720 www.marriott.com/oakmv page 1 of 4 university of california, berkeley • residential and student service programs DOUBLETREE BERKELEY MARINA 200 Marina Boulevard Berkeley, Ca 94710 (2.6 mi) 510-548-7920 www.berkeleymarina.doubletree.com DOWNTOWN BERKELEY INN 2001 Bancroft Way Berkeley, Ca 94704 (0.5 mi) 510-843-4043 downtownberkeleyinn.com EXECUTIVE INN AND SUITES 1755 Embarcadero Oakland, Ca 94606 (7.8 mi) 510-536-6633 www.executiveinnoakland.com FOUR POINTS HOTEL (BY SHERATON) 1603 Powell Street Emeryville, Ca 94608 (4.4 mi) 510-547-7888 866-716-8133 cal rentals fourpointssanfranciscobaybridge.com 2610 Channing Way Berkeley, CA 94720-2272 FREEWAY MOTEL 11645 San Pablo Ave HOURS: El Cerrito, Ca 94530-1747 (1.7 mi) Monday–Friday, (510) 234-5581 10 a.m. -

Guest Houses and Hotels in Boudhanath

Updated December 2015 RYI’s Guide to Guest Houses and Hotels In Boudhanath Index (NPR according to present exchange rate, please look at guest house listing for exact cost.) General Notes ......................................................................................................................... 2 Monastery Guest Houses • Tharlam Guest House (500 NPR) ............................................................................3 • Dondrub Guest House (1500 NPR) ........................................................................ 3 • Shechen Guest House (1011 NPR) .........................................................................4 Low and Middle Range Guest Houses • Lotus Guest House (500 NPR) ................................................................................ 5 • Kailash Guest House (500 NPR) ............................................................................ 5 • Dungkar Guest House (600 NPR) .......................................................................... 6 • Dragon Guest House (600 NPR) ............................................................................. 7 • Bodhi Guest House (700 NPR) ............................................................................... 7 • Comfort Guest House (800 NPR) ............................................................................8 • Pema Guest House (1000 NPR) .............................................................................. 8 • Khasyor Guest House (800 NPR) ......................................................................... -

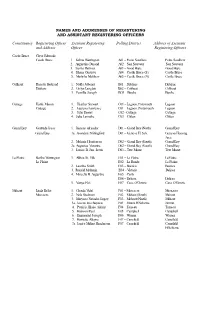

Names and Addresses of Registering and Assistant Registering Officers

NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF REGISTERING AND ASSISTANT REGISTERING OFFICERS Constituency Registering Officer Assistant Registering Polling District Address of Assistant and Address Officer Registering Officers Castle Bruce Cleve Edwards Castle Bruce 1. Kelma Warrington A01 – Petite Soufriere Petite Soufriere 2. Augustina Durand A02 – San Sauveur San Sauveur 3. Sasha Darroux A03 – Good Hope Good Hope 4. Shana Gustave A04 – Castle Bruce (S) Castle Bruce 5. Marlisha Matthew A05 – Castle Bruce (N) Castle Bruce Colihaut Rosette Bertrand 1. Nalda Jubenot B01 – Dublanc Dublanc Dublanc 2. Gislyn Langlais B02 – Colihaut Colihaut 3. Fernillia Joseph BO3 – Bioche Bioche Cottage Hartie Mason 1. Heather Stewart C01 – Lagoon, Portsmouth Lagoon Cottage 2. Laurena Lawrence C01 – Lagoon ,Portsmouth Lagoon 3. Julie Daniel C02 - Cottage Cottage 4. Julia Lamothe C03 – Clifton Clifton Grand Bay Gertrude Isaac 1. Ireneus Alcendor D01 – Grand Bay (North) Grand Bay Grand Bay 1a. Avondale Shillingford D01 – Geneva H. Sch. Geneva Housing Area 2. Melanie Henderson D02 – Grand Bay (South) Grand Bay 2a. Augustus Victorine D02 – Grand Bay (South) Grand Bay 3. Louise B. Jno. Lewis D03 – Tete Morne Tete Morne La Plaine Bertha Warrington 1. Althea St. Ville E01 – La Plaine LaPlaine La Plaine E02 – La Ronde La Plaine 2. Laurina Smith E03 – Boetica Boetica 3. Ronald Mathurin E04 - Victoria Delices 4. Marcella B. Augustine E05 – Carib E06 – Delices Delices 5. Vanya Eloi E07 – Case O’Gowrie Case O’Gowrie Mahaut Linda Bellot 1. Glenda Vidal F01 – Massacre Massacre Massacre 2. Nola Stedman F02 – Mahaut (South) Mahaut 3. Maryana Natasha Lugay F03- Mahaut (North) Mahaut 3a. Josette Jno Baptiste F03 – Jimmit H/Scheme Jimmit 4. -

St. Kitts at a Crossroad

St. Kitts at a Crossroad Rachel Dodds Ted Rogers School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Ryerson University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Jerome L. McElroy Department of Business Administration and Economics, Saint Mary's College, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA Abstract Resumen I Like many island economies, St. Kitts is at a cross- I Como muchas economías isleñas, St. Kitts está en roads. The acceleration of globalization and the decision una encrucijada. La aceleración de la globalización y la of the European Union in 2005 to remove preferential decisión de la Unión Europea en el 2005 de eliminar el treatment for its main industry, sugar cane, have left the tratamiento preferencial para su industria principal, la island with limited options. Tourism has now become caña de azúcar, han dejado opciones limitadas a la isla. the key avenue for economic growth. El turismo se ha convertido ahora en el factor clave para su desarrollo económico. Los destinos pasan por varios Destinations go through various cycles, both popular and ciclos, tanto de popularidad como de inestabilidad, unstable, which are affected by market and tourism afectados por las tendencias del mercado y del turismo, trends as well environmental and social factors. For así como por factores ambientales y sociales. Para many tourism destinations, especially islands, there is muchos destinos turísticos, especialmente las islas, intense competition and weak differentiating factors existe una competencia intensa, los factores diferencia- and the product has become commoditized. As tourism les son débiles y el producto se ha mercantilizado. has been put forth as the key driver for economic Habiéndose presentado el turismo como el factor clave growth and sustainability within the island, long term del desarrollo económico y sostenible de la isla, es nece- strategies need to be put in place to adapt to changing sario implementar estrategias a largo plazo para adap- trends and markets. -

GRAND TOUR of PORTUGAL Beyond Return Date FEATURING the D OURO RIVER VALLEY & PORTUGUESE RIVIERA

Durgan Travel presents… VALID 11 Days / 9 Nights PASSPORT REQUIRED Must be valid for 6 mos. GRAND TOUR OF PORTUGAL beyond return date FEATURING THE D OURO RIVER VALLEY & PORTUGUESE RIVIERA Your choice of departures: April ~ Early May ~ October $ $ TBA* for payment by credit card TBA* for payment by cash/check Rates are per person, twin occupancy, and INCLUDE $TBA in air taxes, fees, and fuel surcharges (subject to change). OUR GRAND TOUR OF PORTUGAL TOUR ITINERARY: DAY 1 – BOSTON~PORTUGAL: Depart Boston’s Logan International Airport aboard our transatlantic flight to Porto, Portugal (via intermediate city) with full meal and beverage service, as well as stereo headsets, available in flight. DAY 2 – PORTO, PORTUGAL: Upon arrival at Francisco Carneiro Airport in Porto, we will meet our Tour Escort, who will help with our transfer. We’ll board our private motorcoach and enjoy a panoramic sightseeing tour en route to our 4-star hotel, which is centrally located. After check-in, the remainder of the day is at leisure. Prior to dinner this evening, we will gather for a Welcome Drink. Dinner and overnight. (D) DAY 3 – PORTO: After breakfast at our hotel, we are off for a full day of guided sightseeing in Porto, Portugal’s second largest city, situated on the right bank of the Douro River. Our tour begins in the Foz area near the mouth of the river. Next, we will visit Pol ácio da Bolsa (the stock exchange) , the Old Trade Hall, the Gold Room, the Arabian Hall, the Clerigos Tower, and Cais da Bibeira. -

Anguilla: a Tourism Success Story?

Visions in Leisure and Business Volume 14 Number 4 Article 4 1996 Anguilla: A Tourism Success Story? Paul F. Wilkinson York University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions Recommended Citation Wilkinson, Paul F. (1996) "Anguilla: A Tourism Success Story?," Visions in Leisure and Business: Vol. 14 : No. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/visions/vol14/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Visions in Leisure and Business by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@BGSU. ANGUILLA: A TOURISM SUCCESS STORY? BY DR. PAUL F. WILKINSON, PROFESSOR FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY 4700KEELE STREET NORTH YORK, ONTARIO CANADA MJJ 1P3 ABSTRACT More than any other Caribbean community, the Anguillans [sic )1 have Anguilla is a Caribbean island microstate the sense of home. The land has been that has undergone dramatic tourism growth, theirs immemorially; no humiliation passing through the early stages of Butler's attaches to it. There are no Great tourist cycle model to the "development" houses2 ; there arenot even ruins. (32) stage. This pattern is related to deliberate government policy and planning decisions, including a policy of not having a limit to INTRODUCTION tourism growth. The resulting economic dependence on tourism has led to positive Anguilla is a Caribbean island microstate economic benefits (e.g., high GDP per that has undergone dramatic tourism growth, capita, low unemployment, and significant passing through the early stages of Butler's localinvolvement in the industry). (3) tourist cycle model to the "development" stage. -

STUDIES on the FAUNA of CURAÇAO and OTHER CARIBBEAN ISLANDS: No

STUDIES ON THE FAUNA OF CURAÇAO AND OTHER CARIBBEAN ISLANDS: No. 91. Frogs of the genus Eleutherodactylusinthe Lesser Antilles by Albert Schwartz (Miami) page Introduction 1 Systematic account 5 Eleutherodactylus urichi Boettger 5 urichi euphronides n. subsp 6 urichi shrevei n. subsp 13 johnstonei Barbour 17 barbudensis (Auffenberg) 30 martinicensis (Tschudi) 32 pinchoni n. sp 45 barlagnei Lynch 51 Discussion 57 Literature 61 The Lesser Antilles consist of those West Indian islands which extend from the Anegada Passage in the north to Grenada in the south.¹) These islands are nomenclatorially divided into two major The Leeward groups: 1) Islands, including Sombrero, Anguilla, St. Martin, St.-Barthélemy [= St. Barts], Saba, St. Eustatius, St. Christopher [= St. Kitts], Nevis, Redonda, Montserrat, ED. - Attention be drawn to the fact that — in these 'Studies' - the *) may terms 'Lesser 'Leeward and 'Windward in Antilles', Islands' Islands' are generally used a different Vols. and meaning (cf. II, p. 24; IV, p. 2; IX, p. 5; XIII, p. 22; XIV, p. 42, follows: Lesser Antilles Islands Trinidad Aruba. Wind- XXI, p. 115) as = Virgin to and ward Group = Virgin Islands to Grenada. Leeward Group = Los Testigos to Aruba. Sombrero Leeward Islands (Carribbees = to Grenada.) = [British denomination]Virgin Grenada. Islands to Dominica. Windward Islands = [British denomination]Martiniqueto 2 Barbuda, and Antigua, and 2) the Windward Islands, including Guadeloupe (with its satellites Marie-Galante, La Désirade, Les Saintes), Dominica, Martinique, St. Lucia, St. Vincent, Grenada, and Barbados. Geologically, the Lesser Antilles can be divided into two those which mountainous - the so-called major groups: 1) are inner-chain islands - which are younger and more recently volcanic (Saba to Grenada, and including the western or Basse-Terre portion of Guadeloupe, and Les Saintes), and 2) the older, gently rolling limestone islands - the so-called outer-chain islands (Som- brero to Marie-Galante, and including the Grande-Terre portion of Guadeloupe, La Desirade, and Barbados). -

Creative Resources for Attractive Seaside Resorts: the French Turn

Journal of Investment and Management 2015; 4(1-1): 78-86 Published online February 11, 2015 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/jim) doi: 10.11648/j.jim.s.2015040101.20 ISSN: 2328-7713 (Print); ISSN: 2328-7721 (Online) Creative resources for attractive seaside resorts: The French turn Anne Gombault 1, Ludovic Falaix 2, Emeline Hatt 3, Jérôme Piriou 4 1Research Cluster for Creative Industries, KEDGE Business School, Bordeaux-Marseille, France 2Laboratoire ACTé EA 4281, Blaise Pascal University, Clermont-Ferrand France 3Laboratoire interdisciplinaire en urbanisme – EA 889, Aix Marseille Univeristy, Aix Marseille, France 4Tourism Management Institute, La Rochelle Business School, La Rochelle, France Email address: [email protected] (A. Gombault), [email protected] (L. Falaix), [email protected] (E. Hatt), [email protected] (J. Piriou) To cite this article: Anne Gombault, Ludovic Falaix, Emeline Hatt, Jérôme Piriou. Creative Resources for Attractive Seaside Resorts: The French Turn. Journal of Investment and Management. Special Issue: Attractiveness and Governance of Tourist Destinations. Vol. 4, No. 1-1, 2015, pp. 78-86. doi: 10.11648/j.jim.s.2015040101.20 Abstract: This article presents a qualitative analysis of the specific strategies used by coastal resorts in the South of France to valorise their creative regional resources. These strategies emerge from factors of change in the trajectories of the resorts: change in the relationship between man and nature, environmental turning point and the need for sustainability, emergence of creative tourism centred on recreation, sport and culture. The research is supported by three case studies, Biarritz, Lacanau and Martigues, and assesses the constraints that arise in terms of design and management of coastal resorts and tourist areas, against a background of numerous conflicting requirements, including attractiveness and sustainability. -

Sales Manual

DominicaSALES MANUAL 1 www.DiscoverDominica.com ContentsINTRODUCTION LAND ACTIVITES 16 Biking / Dining GENERAL INFORMATION 29 Hiking and Adventure / 3 At a Glance Nightlife 4 The History 30 Shopping / Spa 4 Getting Here 31 Turtle Watching 6 Visitor Information LisT OF SERviCE PROviDERS RICH HERITAGE & CULTURE 21 Tour Operators from UK 8 Major Festivals & Special Events 22 Tour Operators from Germany 24 Local Ground Handlers / MAIN ACTIVITIES Operators 10 Roseau – Capital 25 Accommodation 18 The Roseau Valley 25 Car Rentals & Airlines 20 South & South-West 26 Water Sports 21 South-East Coast 2 22 Carib Territory & Central Forest Reserve 23 Morne Trois Pitons National Park & Heritage Site 25 North-East & North Coast Introduction Dominica (pronounced Dom-in-ee-ka) is an independent nation, and a member of the British Commonwealth. The island is known officially as the Commonwealth of Dominica. This Sales Manual is a compilation of information on vital aspects of the tourism slopes at night to the coastline at midday. industry in the Nature Island of Dominica. Dominica’s rainfall patterns vary as well, It is intended for use by professionals and depending on where one is on the island. others involved in the business of selling Rainfall in the interior can be as high as Dominica in the market place. 300 inches per year with the wettest months being July to November, and the As we continue our partnership with you, driest February to May. our cherished partners, please help us in our efforts to make Dominica more well known Time Zone among your clients and those wanting Atlantic Standard Time Zone, one hour information on our beautiful island. -

Latin'amnerica and the Ca Aribbean

Latin'Amnerica and the Caaribbean -- Technical Department I . o Regionat Studies Program Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 7 The Evolution, Situation, and Prospects of the Electric Power Sector in the Public Disclosure Authorized Latin American and Caribbean Countries Volume 11 Descriptionsof IndividualPower Sectors by Public Disclosure Authorized Infrastructure& Energy Division and LatinAmerican Energy Organization (OLADE) August 1991 Public Disclosure Authorized Papers in this series are not formal publications of the World Bank. They present preliminary and unpolished results of country analysis or research that is circulated to encourage discussion and comment; citation and the use of such a paper should take account of its provisional character. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and should not be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, to its afftliated organizations, or to members of its Board of Executive Directors or the countries they represent. This document was prepared by World Bank and OLADE teams on the basis of data provided by the electric power sectors of the LAC region and data available in World Bank and OLADE files. VOLUME 11 TABLE OF C(OMTENTS PREFACE INDIVIDUAL COUNTRY REPORTS PAGES 1. Argentina ARG-1 - 11 2. Barbados BAR-1 - 10 3. Belize BEZ-1 - 9 4. Bolivia BOL-1 - 9 5. Brazil BRA-I - 11 6. Chie CHL-1 - 9 7. Colombia CLM-1 - 10 8. Costa Rica COS-1 - 10 9. Dominica DMC-1- 9 10. Dominican Republic DOM-1- 10 11. Ecuador ECU-I - 10 12. El Salvador ESL-1 - 10 13. -

Hitting Disaster Risk for Six!

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Caribbean Conference Proceedings fromthe2019UR CaribbeanConference Proceedings from the 2019 UR Caribbean Confernce UR Proceedings from the 2019 This publication is made up of a series of submissions from technical session leads of the Understanding Risk Caribbean Conference. These submissions were compiled and edited by the World Bank Group. The content and findings of this publication do not reflect the views of GFDRR, the World Bank Group, or the European Union, and the sole responsibility for this publication lies with the authors. The GFDRR, World Bank Group, and European Union are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Washington, DC, November 2019 Edited by Tayler Friar Designed by Miki Fernández ([email protected]), Washington, DC ©2019 by The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 USA All rights reserved. Bahamas. Based on NASA image. 27–31 May 2019 Barbados Organized by: ii From Risk to Resilience: A Foundation for Action Cosponsors: In collaboration with: #URCaribbean #ResilientCaribbean iii Proceedings from the 2019 UR Caribbean Conference Contents vi Letter from Anna Wellenstein, Regional Director, Sustainable Development Latin America and the Caribbean vii Letter from Ronald Jackson, Executive Director, CDEMA viii Acknowledgments xi Foreword xii UR Caribbean by the Numbers xiii Abbreviations 1. -

6Y

6y ~;c"ariJ f!1tetc"er I .< • '"Ii> I ;. 1 ." ; QQ[-tll~(]aJI. Q(]lLtrt tQ1;-l~LQLl(]latvy ~llL(it(]~ -,,' // THE ADLITH BROWN MEMORIAL LECTURE SERIES I. 1985 Bahamas Courtney Blackman "A Heterdox Approach to the Adjustment Problem" 2. 1986 St. Kitts Maurice Odie "Transnational Banks and the Problems of Small Debtors" 3. 1987 Belize William Demas "Public Administration for Sustained Development" 4. 1988 Trinidad & Edwin Carrington Tobago "The Caribbean and Europe in the I 990s" 5. 1989 Barbados Bishnodat Persaud "The Caribbean in Changing World: We Must Not Fail" 6. 1990 Guyana Karl Bennett "Monetary Integration in CAR/COM 7. 1991 Belize Owen Jefferson "Liberalization of the Foreign Exchange System in Jamaica', 8. 1992 Bahamas Havelock Brewster "The Caribbean Community in a Changing lnternational Environment Towards the Next Century" 9. 1993 Trinidad& Richard Bernal Tobago "The Caribbean Caught in the Cross Currents of Globalization and Regional ism" 10. 1994 Jamaica Dwight Venner "Institutional Changes in the Process of National Development: The Case for an Independent Central Bank" 11. 1995 St. Kitts Neville Nicholls "Taking Charge of Our Future Development" 12. 1996 Trinidad & Richard Fletcher Tobago "After Four Decades of Economic Malpractice: What are The Options For The Caribbean?" Richard Fletcher, an economist and an attorney-at-law, is a Jamaican national who lives and works abroad but who shares a strong sense of continued commitment to the Caribbean Region, having been a member ofthe early group ofWest Indian Social Science students at The University ofthe West Indies. Mr. Fletcher studied Economics at The University of the West Indies, Mona Campus, graduating with a B.Sc.