Benjamin and Barthes on Photography and History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophical Discussion of Representation

International Visual Literacy Association, Cheyenne, 1996 A PHILOSOPHICAL DISCUSSION OF REPRESENTATION One of the most basic theoretical areas in the study of visual communication and visual literacy is the nature of representation. Much of the discussion of this topic comes from either philosophy or aesthetics. This paper reviews some of the more important writings in this area in an attempt to develop a model of representation. The primary works reviewed include: E. H. Gombrich, "The Visual Image;" "Representation and Misrepresentation" Nelson Goodman, Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols, "Representation Re- presented" Paul Messaris, Visual Literacy: Image, Mind & Reality David Novitz, "Picturing" Marx Wartofsky, "Pictures, Representation, and Understanding;" "Visual Scenarios: The role of Representation in Visual Perception" Richard Wollheim, "Representation: The Philosophical Contribution to Psychology;" Pictures and Language;" and "Art, Interpretation, and Perception" In describing the requirements for a general theory of representation, Wollheim says it must answer two questions: What is it to represent? (what is the relationship between the representation and the something that it is of?) What, in the narrow sense of the term, is a representation? Using his two questions to guide our analysis, we find that the major theoretical issues that need to be investigated include: Is pictorial representation based on natural resemblance or convention? What is the relationship between pictures and reality? Finally, as part of this review, we are investigating if it is possible to develop an overriding theory of representation that accommodates the various issues and viewpoints. What is the relationship between pictures and reality? In beginning this discussion, let's first look at Wollheim's second question about what is a representation. -

A Prologue to Charles Sanders Peirce's Theory of Signs

In Lieu of Saussure: A Prologue to Charles Sanders Peirce’s Theory of Signs E. San Juan, Jr. Language is as old as consciousness, language is practical consciousness that exists also for other men, and for that reason alone it really exists for me personally as well; language, like consciousness, only arises from the need, the necessity, of intercourse with other men. – Karl Marx, The German Ideology (1845-46) General principles are really operative in nature. Words [such as Patrick Henry’s on liberty] then do produce physical effects. It is madness to deny it. The very denial of it involves a belief in it. – C.S. Peirce, Harvard Lectures on Pragmatism (1903) The era of Saussure is dying, the epoch of Peirce is just struggling to be born. Although pragmatism has been experiencing a renaissance in philosophy in general in the last few decades, Charles Sanders Peirce, the “inventor” of this anti-Cartesian, scientific- realist method of clarifying meaning, still remains unacknowledged as a seminal genius, a polymath master-thinker. William James’s vulgarized version has overshadowed Peirce’s highly original theory of “pragmaticism” grounded on a singular conception of semiotics. Now recognized as more comprehensive and heuristically fertile than Saussure’s binary semiology (the foundation of post-structuralist textualisms) which Cold War politics endorsed and popularized, Peirce’s “semeiotics” (his preferred rubric) is bound to exert a profound revolutionary influence. Peirce’s triadic sign-theory operates within a critical- realist framework opposed to nominalism and relativist nihilism (Liszka 1996). I endeavor to outline here a general schema of Peirce’s semeiotics and initiate a hypothetical frame for interpreting Michael Ondaatje’s Anil’s’ Ghost, an exploratory or Copyright © 2012 by E. -

Visual Semiotics: a Study of Images in Japanese Advertisements

VISUAL SEMIOTICS: A STUDY OF IMAGES IN JAPANESE ADVERTISEMENTS RUMIKO OYAMA THESIS SUBMIITED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON iN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF LONDON NOVEMBER 1998 BIL LONDON U ABSTRACT 14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 15 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 16 1.1 THE PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH 16 1.2 DEVELOPMENT OF RESEARCH INTERESTS 16 1.3 LANGUAGE VERSUS VISUALS AS A SEMIOTIC MODE 20 1.4 THE ASPECT OF VISUAL SEMIOTICS TO BE FOCUSED ON: Lexis versus Syntax 23 1.5 CULTURAL VALUE SYSTEMS IN VISUAL SYNTAX: A challenge to the notion of universality 24 Chapter Ii THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 26 2.1 INTRODUCTION 26 2.2 LITERATURE SURVEY ON STUDIES OF IMAGES 27 2.2.1 What is an image? 27 2.2.2 Art history/Art theories 29 2.2.3 Sociological approaches to visual images 36 2.2.4 Cultural approaches to visual images 44 2.2.4.1 Visual images as cultural products 45 2.2.4.2 Visual images from linguistic perspectives 50 2.2.5 Semiotic approaches to visual images 54 2.2.5.1 Saussure, Barthes (traditional semiology I semiotics) 54 2.2.5.2 Film semiotics 59 2 2.2.5.3 Social Semiotics 61 2.2.6 Reflection on the literature survey 66 2.3 A THEORY FOR A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF THE VISUAL 71 2.3.1 Visual semiotics and the three metafunctions 72 2.3.1.1 The Ideational melafunction 73 2.3.1.2 The Textual metafunction 75 2.3.1.3 The Interpersonal metafunction 78 2.4 VERBAL TEXT IN VISUAL COMPOSITION: Critical Discourse Analysis 80 23 INTEGRATED APPROACH FOR A MULTI-MODAL ANALYSIS OF VISUAL AND VERBAL TEXTUAL OBJECTS -

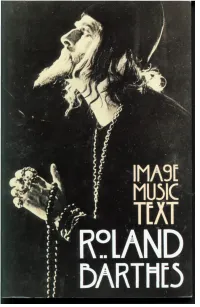

Image Music Text\

IMAGE MUSIC TEXT ROLAND BARTHES was bom in 1915 and died in 1980. At the time of his death he was Professor at the College de France. Among his books are Le Degre zero de I'ecriture (1953), Mythologies (1957), Elements de semiologie (1964), S/Z (1970), L'Empire des signes (1970), Sade, Fourier, Loyola (1971), Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes (1975), Fragments d'un discours amoureux (1977), and La Chambre claire (1980). STEPHEN HEATH is a Fellow ofJesus College and Reader in Cultural Studies in the University of Cambridge. His books include a study of Barthes, Vertige du deplacement (1974), and, most recently, Gustave Flaubert: 'Madame Bovary'(\992). ROLAND BARTHES Image Music Text Essays selected and translated by Stephen Heath FontanaPress An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Fontana Press An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77-85 Fulham Palace Road Hammersmith, London, w6 8JB www.fireandwater.com Published by Fontana Press 1977 14 Copyright © Roland Barthes 1977 English translation copyright © Stephen Heath 1977 Illustrations I, XI, XII, XIII, XIV and XV are from the collection of Vincent Pinel ISBN 0 00 686135 0 Set in Times Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Peirce on the Passions: the Role of Instinct, Emotion, and Sentiment in Inquiry and Action Robert J

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-12-2008 Peirce on the Passions: The Role of Instinct, Emotion, and Sentiment in Inquiry and Action Robert J. Beeson University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Beeson, Robert J., "Peirce on the Passions: The Role of Instinct, Emotion, and Sentiment in Inquiry and Action" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/134 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Peirce on the Passions: The Role of Instinct, Emotion, and Sentiment in Inquiry and Action by Robert J. Beeson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Martin R. Schönfeld, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Roy C. Weatherford, Ph.D. Sidney Axinn, Ph.D. Charles B. Guignon, Ph.D. Stephen P. Turner, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 12, 2008 Keywords: mind, sign, self, consciousness, pragmatism, synechism, habit, belief, self-control, community © Copyright 2008, Robert J. Beeson Dedication In Memory of Willis H. Truitt Acknowledgments I wish to recognize several people, without whose contributions this dissertation would not have been completed. I would like to thank Kelly A. -

Learning from Charles Sanders Peirce's Semoitic

STJHUMRev Vol. 2-2 1 CHARLES SANDERS PEIRCE’S THEORY OF SIGNS, MEANING, AND LITERARY INTERPRETATION by E. San Juan, Jr. Now thought is of the nature of a sign. In that case, then, if we can find out the right method of thinking and can follow it out—the right method of transforming signs—then truth can be nothing more nor less than the last result to which the following out of this method would ultimately carry us. --Charles Sanders Peirce D espite 9/11, “United We Stand,” and the USA Patriot Act, it seems that we are still afflicted by logocentrism and essentializing metanarratives. Decades of inoculation by deconstructive serums—first introduced by Jacques Derrida’s 1966 lecture at Johns Hopkins University entitled “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences”—have failed to immunize us, readers and scholars, from lusting for truth, presence, or origin far removed “from freeplay and from the order of the sign” (1986, 492). The order of the sign instructs us, following Saussure’s dictum, that the relation between the signifier (word), its referent (thing or idea) and its signified (meaning) is arbitrary. Not in the sense that words mean just anything you decide it means. There is no natural resemblance between sound-image, referent, and idea; the link between signifier and signified is based on alterable social convention. Saussure taught us that the meaning or value of a sign in any language results from its difference to all the other signs in that language. What is important is not history (diachrony) nor reality (the referent), but the system of differential relations among signs (synchrony). -

Indexicality and the Depiction of Time on the Radicality of Vanishing Zone

INDEXICALITY AND THE DEPICTION OF TIME ON THE RADICALITY OF VANISHING ZONE Liat Lavi Myths of Indexicality The term indexicality stems from the semiotics of linguist and philosopher Charles S. Peirce, and his categorization of signs into icon, symbol and index1. An icon, according to Peirce, is a sign based on resemblance, a symbol is a sign based on normative grounds, and an index is a sign that has some causal relation to the object is signifies. Indexicality has become a key term in the discourse on photography. It stands to mark the direct relation a photograph has to an outer reality, the way the photographic image is a physical trace or consequence of the world it depicts. The indexical nature of the photograph is challenged time and again by critics who point out that the use of indexicality as the mark of photography, portrays it as passive, while in fact, photographs are the result of an active agent, favoring and singling out a distinct and chosen perspective. We may no longer regard photographs as documentation, but rather as manufacturing, but indexicality remains a key term in the field of photo-theory, for it seems to capture a distinct feature of photography that sets it apart from other forms of art, such as painting and sculpture. The peculiar way in which photography makes use of light (existing light, light that is ‘out there’) in producing an image is something that simply cannot be denied. Photography is not only indexical, of course; it is undoubtedly symbolic, in that it builds on 1 See: Charles S. -

The Depiction of the Worst Thing on the Meaning and Use of Images of the Terrible

The Depiction of the Worst Thing On the Meaning and Use of Images of the Terrible Bart Verschaffel Résumé On argumente parfois que l’impact et la puissance d’une image sont plus grands lorsque celle-ci représente des choses terribles avec un tel réalisme que le spectateur réagit à la scène comme si elle avait lieu sous ses yeux. Selon d’aucuns, le fait d’être choqué par une image constitue la meilleure manière de prendre conscience d’une situation et de réagir adéquatement sur le plan politique ou moral. L’image photographique, qui capte – suivant Roland Barthes – « chimiquement » le ça a été, et la télévision, sont devenues les médias majeurs qui montrent « objectivement » l’horreur : la nature de ces médias est considérée comme une garantie de la « vérité » de l’image, tandis que toute représentation figurative ou toute description est considérée comme une construction qui crée inévitablement du « sens » et ne peut ipso facto rendre justice à ce qui s’est produit, ce qui est « inimaginable » ou « irreprésentable ». Cet article prend comme point de départ l’idée que la révulsion et le choc provoqués par la vision (d’une image) de l’horreur sont des réactions physiques s’accompagnant (aussi) d’une forme de refus, rendant une personne insensible et n’impliquant pas en elles-mêmes une véritable prise de conscience. À l’encontre de la théorie du punctum de Roland Barthes, nous argumentons que les images ne sont pas « naturelles », mais artificielles, et que des « images fortes » sont produites et composées de manière à ce qu’elles « heurtent » l’esprit et structurent la mémoire. -

The Semiotics of Celebrity at the Intersection of Hollywood and Broadway

THE SEMIOTICS OF CELEBRITY AT THE INTERSECTION OF HOLLYWOOD AND BROADWAY Kevin Calcamp A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2016 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Kristen Rudisill Graduate Faculty Representative Cynthia Baron Lesa Lockford © 2016 Kevin Calcamp All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor In 1990, Michael L. Quinn, in his essay, “Celebrity and the Semiotics of Acting,” considered celebrity phenomenon—and its growth in the latter part of the 20th century—and the affect it had on media, society, and the role and performance of the actor. Throughout the first fifteen years of the 21st century, there has been a multitude of film and television stars headlining in Broadway and Off-Broadway shows. Despite this phenomena, there is currently an absence of scholarship investigating how the casting of Hollywood stars in stage productions affects those individuals in the theatre audience. In this dissertation, I identify, using a variety of semiotic theories, ways in which celebrity is signified by exploring 21st century Broadway and Off- Broadway productions with Hollywood film and television star casting. Hollywood is an industry that thrives on perpetuating celebrity. Film and television stars are products that need to cultivate a consumer base. Every star in Hollywood has specific attributes that are deemed valuable; these values are then marketed and sold to the public, creating a connection between the star and certain values. A film or television star is an established actor who has received fame and acclaim for a least one role that was critically lauded, or their past roles become a part of their value and product.