Central Asia the Caucasus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations System and Specialized Agencies

21 December 2015 FRENCH / ENGLISH Dialogue du Haut Commissaire sur les défis de protection: Comprendre les causes profondes des déplacements et y faire face Genève, 16-17 décembre 2015 Liste des participants High Commissioner’s Dialogue on Protection Challenges: Understanding and addressing root causes of displacement Geneva, 16-17 December 2015 List of participants 1 Page I. États – States ......................................................................................................................... 3 II. Système des Nations Unies et agences spécialisées – United Nations System and specialized agencies .............................................................................................................. 28 III. Organisations intergouvernementales – Intergovernmental organizations ........................... 31 IV. Autres entités – Other entities .............................................................................................. 33 V. Experts – Experts .................................................................................................................. 36 VI. Organisations non gouvernementales – Non-governmental organizations ........................... 40 2 I. États – States ALGÉRIE - ALGERIA S.E. M. Boudjemâa DELMI Ambassadeur extraordinaire et plénipotentiaire Représentant permanent auprès de l’Office des Nations Unies à Genève M. Toufik DJOUAMAA Ministre conseiller Mission permanente auprès de l'Office des Nations Unies à Genève M. Mohamed Lamine HABCHI Conseiller Mission permanente auprès -

AIBA Youth World Boxing Championships Yerevan 2012 Athletes Biographies

AIBA Youth World Boxing Championships Yerevan 2012 Athletes Biographies 49KG – HAYRIK NAZARYAN – ARMENIA (ARM) Date Of Birth : 30/08/1995 Club : Working Shift Sport Company Coach : Marat Karoyan Residence : Yerevan Number of bouts : 60 Began boxing : 2002 2012 – Klichko Brothers Youth Tournament (Berdichev, UKR) 6th place – 49KG Lost to Sultan Abduraimov (KAZ) 12:3 in the quarter-final; Won against Danilo Pleshkov (UKR) AB 2nd round in the first preliminary round 2012 – Armenian Youth National Championships 1st place – 49KG Won against Andranik Peleshyan (ARM) by points in the final; Won against Taron Petrosyan (ARM) by points in the semi-final 2012 – Pavlyukov Youth Memorial Tournament (Anapa, RUS) 7th place – 49KG Lost to Keith Flavin (IRL) 30:6 in the quarter-final 2011 – AIBA Junior World Championships (Astana, KAZ) 7th place – 46KG Lost to Georgian Tudor (ROM) 15:14 in the quarter-final; Won against Dmitriy Asanov (BLR) 22:14 in the first preliminary round 2011 – European Junior Championships (Keszthely, HUN) 5th place – 46KG Lost to Timur Pirdamov (RUS) 17:4 in the quarter-final; Won against Zsolt Csonka (HUN) RSC 2nd round in the first preliminary round 2011 – Armenian Junior National Championships 1st place – 46KG 49KG – ROBERT TRIGG – AUSTRALIA (AUS) Date Of Birth : 03/01/1994 Place Of Birth : Mount Gambier Height : 154cm Club : Mt. Gambier Boxing Club Coach : Colin Cassidy Region : South Australia Began boxing : 2010 2012 – Oceanian Youth Championships (Papeete, TAH) 1st place – 49KG Won against Martin Dexon (NRU) by points -

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

Central Asia

U.S. ONLINE TRAINING FOR OSCE, INCLUDING REACT Module 6. Central Asia This module introduces you to central Asia and the OSCE’s work in: • Kazakhstan • Turkmenistan • Uzbekistan • Kyrgyzstan • Tajikistan 1 Table of Contents Overview. 3 Central Asia. 4 States before the Soviet period. 7 International organizations. 9 Caspian Oil. 10 Getting the oil out. 12 Over-fishing and pollution. 14 Water. 15 Kazakhstan. 18 Geography. 19 People. 20 Government. 21 Before Russian rule. 22 Under Russian and Soviet rule. 23 From Perestroika to independence. 25 Domestic politics. 26 Ethnic relations. 31 Internal security. 32 Foreign relations. 33 Kazakhstan culture. 40 Turkmenistan. 42 Geography. 43 People. 44 Government. 45 Basic geography. 46 Historical background. 47 Domestic politics. 48 Ethnic relations. 53 Foreign relations. 54 Turkmenistan culture. 58 Uzbekistan. 63 Geography. 64 People. 65 Government. 66 Basic geography. 67 Historical background. 68 The Muslim civilization of Bukhara and Samarkand. 69 The Turko-Persian civilization. 70 Under Russian and Soviet rule. 71 Perestroika and independence. 72 Domestic politics. 73 Economics and politics. 77 Islam and politics. 78 MODULE 6. Central Asia 2 Ethnic relations. 80 Foreign relations. 81 Uzbekistan culture. 85 Kyrgyzstan. 89 Geography. 90 People. 91 Government. 92 Basic geography. 93 Historical background. 94 The Osh conflict and the ‘Silk Revolution’. 95 Ethnic relations. 96 Domestic politics. 97 Foreign relations. 106 Culture. 111 Tajikistan. 116 Geography. 117 People. 118 Government. 119 Four regions of Tajikistan. 120 Historical background. 121 The civil war. 122 Nature of the war. 124 Negotiations and the peace process. 125 Politics, economics and foreign affairs. 130 Domestic politics. -

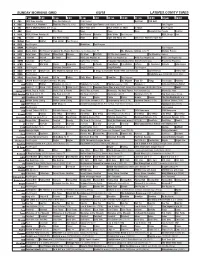

Sunday Morning Grid 6/3/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/3/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Big Deal PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2018 French Open Tennis Fourth Round. (N) Å Paid Program 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Memorial Day Parade IndyCar 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday News Paid Tiger and Rocco (N) 2018 U.S. Women’s Open Golf 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Burns-Story The Forever Wisdom of Dr. Wayne Dyer Tribute to Dr. Wayne Dyer. Å The Migraine Solution (TVG) Å Memory Rescue 28 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Kid Stew Biz Kid$ JFK The Last Speech Å The Wrecking Crew Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho El Coyote Emplumado (1983) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Panamerican Games - Men Athlete Profiles

Panamerican Games - Men Athlete Profiles 49KG – JUNIOR LEANDRO ZARATE – ARGENTINA (ARG) Date Of Birth : 01/10/1989 Place Of Birth : Buenos Aires Coach : Dario Mattioni Club : La Patriada Residence : Buenos Aires Stance : Orthodox Number of training hours : 21 in a week Number of bouts : 105 Began boxing : 2002 2015 – Panamerican Games Qualifier (Tijuana, MEX) 6th place – 49KG Lost to Yubergen Martinez (COL) 3:0 in the quarter-final 2015 – World Series of Boxing Season 2015 13th Round – 49KG Won against Erzhan Zhomart (KAZ) 3:0 2015 – World Series of Boxing Season 2015 11th Round – 49KG Lost to Patrick Barnes (IRL) 3:0 2015 – World Series of Boxing Season 2015 7th Round – 49KG Won against Magomed Ibiyev (RUS) 3:0 2015 – World Series of Boxing Season 2015 3rd Round – 49KG Lost to Dawid Jagodzinski (POL) 3:0 2014 – La Romana Cup (La Romana, DOM) 6th place – 49KG Lost to Carlos Quipo (ECU) 3:0 in the quarter- final 2014 – World Series of Boxing Season 2013/2014 10th Round – 49KG Won against Ovidiu Berceanu (ROM) 3:0 2012 – AIBA American Olympic Qualification Tournament (Rio de Janeiro, BRA) participant – 49KG Lost to Ceiber David Avila (COL) 13:7 in the first preliminary round 2011 – Panamerican Games (Guadalajara, MEX) participant – 49KG Lost to Jantony Ortiz (PUR) 10:5 in the first preliminary round 2011 – AIBA World Championships (Baku, AZE) participant – 49KG Lost to Ceiber David Avila (COL) 14:13 in the second preliminary round; Won against Charlie Edwards (ENG) 17:15 in the first preliminary round 2011 – 1st Panamerican Games Qualifier -

2019 EUBC European Confederation Junior Boxing Championships – Male Athlete Profiles

2019 EUBC European Confederation Junior Boxing Championships – Male Athlete Profiles 46KG – KHACHATUR MANUKYAN – ARMENIA (ARM) Date Of Birth : 10/08/2004 Place Of Birth : Lori Club : Dinamo Residence : Lori 2019 – Armenian Junior National Championships 1st place – 46KG Won against Henrik Sahakyan (ARM) 5:0 in the final; Won against Arman Voskanyan (ARM) 5:0 in the semi-final 2018 – Armenian Schoolboys National Championships 1st place – 38.5KG Won against Sargis Tumanyan (ARM) 5:0 in the final; Won against Artur Ohanyan (ARM) 5:0 in the semi-final 2018 – Yerevan City Schoolboys Championships (Yerevan, ARM) 1st place – 38.5KG 2017 – Armenian Schoolboys National Championships 2nd place – 38.5KG Lost to Vakhran Arshakyan (ARM) 4:1 in the final; Won against Manvel Petrosyan (ARM) 5:0 in the semi-final 46KG – NIJAT HUSEYNOV – AZERBAIJAN (AZE) Date Of Birth : 31/03/2003 Place Of Birth : Baku Height : 168cm Coach : Vugar Aghalarov Club : Tahsil Residence : Baku Stance : Orthodox Nickname : Buratino His most influential person : His grandfather Boxing idol : Muhammadrasul Majidov Hobby : Boxing His favourite food : Pizza Number of training hours : 12 in a week Number of bouts : 46 Began boxing : 2014 2019 – Heydar Aliyev Junior Cup (Baku, AZE) 1st place – 46KG Won against Mehmet Cinar (TUR) WO in the final; Won against Bekzod Kholdarov (UZB) 4:0 in the semi-final; Won against Kenje Muratully (KAZ) 4:1 in the quarter-final 2019 – Danilchenko Prizes Junior Tournament (Kharkiv, UKR) 1st place – 46KG Won against Bohdan Rogozniy (UKR) 5:0 in the final; -

740837 334.Pdf

Case 19-10303-KJC Doc 334 Filed 06/03/19 Page 1 of 313 Case 19-10303-KJC Doc 334 Filed 06/03/19 Page 2 of 313 EXHIBIT A 1515 GEEnergy Holdings, LLC,Case et al. - U.S.19-10303-KJC Mail Doc 334 Filed 06/03/19 Page 3 of 313 Served 5/13/2019 10 TEMPLE PLACE, LP 100 ELTON STREET LLC 100 POWERS STREET 10 TEMPLE PLACE 975 WALTON AVE 300 EAST OVERLOOK #333 BOSTON, MA 02111 BRONX, NY 10452 PORT WASHINGTON, NY 11050 1005 GREENE AVE LLC 101 MONMOUTH STREET LLC 101 ST LAUNDRYMAT INC 1005 GREENE AVE PO BOX 590249 1814 3 AVE STO BROOKLYN, NY 11221 NEWTON, MA 02459 MANHATTAN, NY 10029 10132 101ST STREET REALTY LLC 103 CHOPSTICKS HOUSE 104 CANAL ST. 10132 101 ST 10307 NORTHERN BLVD 104 CANAL ST OZONE PARK, NY 11416 CORONA, NY 11368 NEW YORK, NY 10002 1068 WINTHROP STREET LLC 108 JAMAICA LAUNDROMAT 109 REALTY (2010 )LLC 1068 WINTHROP ST 10438 JAMAICA AVE PO BOX 573 BROOKLYN, NY 11212 RICHMOND HILL, NY 11418 NEW YORK, NY 10030 1092 THE PRESIDENT'S LOUNGE LLC 10TH AVE BURRITO 10TH STREET LAUNDROMAT 5 S ALLEN ST 801 BELMAR PLAZA 286 E 10TH ST ALBANY, NY 12208 BELMAR, NJ 07719 NEW YORK, NY 10009 11 CHINATOWN LAUNDROMAT 111 HESTER CORP. 1110-1120 BEACON ST LLC SHUN WEI ZHENG9 DELANCEY ST 111 HESTER ST STO 1120 BEACON ST NEW YORK, NY 10002 NEW YORK, NY 10002 BROOKLINE, MA 02446 1120 GRANT LLC 1145 RANDALL LLC 116 MADISON STREET PO BOX 521 1147 RANDALL AVE ENT 65 BAYWARD ST HEWLETT, NY 11557 BRONX, NY 10474 NEW YORK, NY 10013 11602 METROPOLITAN AVENUE LLC 1170 BROADWAY TENANT LLC 118-20 OCEAN PROMENA 195 EAST AVE 1170 BROADWAY 1111 44TH DRC O VINTAGE REAL ESTATE -

GLORY 47 LYON & GLORY 47 SUPERFIGHT SERIES Le

GLORY 47 LYON & GLORY 47 SUPERFIGHT SERIES Le Championnat du Monde de kick boxing a enflammé le palais des sports Lyon Gerland ! Samedi 28 octobre 2017, GLORY a fait voyager son championnat du monde de Chine à Lyon en France. Pas un siège de libre… Plus de 5 000 spectateurs pour cette 5ème édition en France ! Une soirée qui a tenu toutes ses promesses tant sur la qualité des combats que sur l’ambiance survoltée. Avec plus de 4h de show intense, cette édition du GLORY à Lyon restera dans les archives. ! Voici les liens des photos et rushs de l’événement : PHOTOS GLORY 47 LYON & GLORY 47 SUPERFIGHT SERIES >> Galerie photos << >> Crédit @James Law, GLORY Sports International << VIDÉOS GLORY 47 LYON & GLORY 47 SUPERFIGHT SERIES Les rushs vidéos sont à utiliser dans les 48 heures de l’événement. Pour une autre utilsiation et un complément de vidéos, contactez-nous. >> Rush vidéos << >> Crédit @ GLORY Sports International << RÉSULTATS COMPLETS DE LA SOIRÉE : o Glory SuperFights Series 77kg : Jimmy Vienot (FRA) vs Alim Nabiyev 85kg : Ahaggan Yassine (FRA) vs Maxime Vorovski (HOL) 53kg : Anissa Meksen (FRA) vs Funda Alkayis (TUR) 95kg : Florent Kaouchi (FRA) vs Abdarhmane Coulibaly (FRA) 65kg : Dylan Salvador (FRA, Lyon) vs Massaro Glunder o Glory 47 Lyon Demi-finale A 65kg : Fabio Pinca (FRA, Lyon) vs Anvar Boynazarov (USA) Demi-finale B 65kg : Azize Hlali (FRA) vs Abdellah Ezbiri (FRA) 77kg : Cédric Doumbé (FRA) vs Yohan Lidon (FRA, Lyon) Final 65kg : Abdellah Ezbiri (FRA) vs Anvar Boynazarov (USA) 95kg : Artem Vakhitov (RUS) vs Ariel Machado (BRE) WORLD TITLE CHAMPION Artem Vakhitov (RUS) A propos de GLORY: Fondé en 2012, GLORY appartient et est organisé par GLORY Sports International (GSI), une organisation professionnelle d’arts martiaux et un fournisseur de contenus télévisés basé à Denver, Amsterdam, et Singapour. -

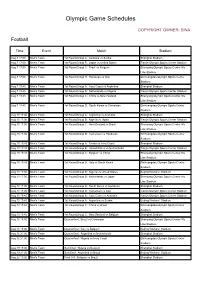

Download Schedule(PDF)

Olympic Game Schedules COPYRIGHT OWNER: SINA Football Time Event Match Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Australia vs Serbia Shanghai Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Japan vs United States Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : Brazil vs Belgium Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : Honduras vs Italy Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Ivory Coast vs Argentina Shanghai Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Netherlands vs Nigeria Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : China vs New Zealand Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : South Korea vs Cameroon Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Argentina vs Australia Shanghai Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Nigeria vs Japan Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : New Zealand vs Brazil Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : Cameroon vs Honduras Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Serbia vs Ivory Coast Shanghai Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : United States vs Netherlands Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : Belgium vs China Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu -

Tke Silk Road Connecting Cultures, Creating Trust

Tke Silk Road Connecting Cultures, Creating Trust 2002 SMITHSONIAN FOLKLIFE F On the National Mall, Washington. D.C. ' ' \ ' The Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage partners with the Silk Road Project, Inc. to present The Silk Road Connecting Cultures, Creating Trust the 36th annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival On the National Mall. Washington. D.C. June 26-30. July 3-7. 2002 Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 750 gth Street, NW Suite 4100 Washington, DC 2056o-og$3 www.folklife.si.edu ©2002 by the Smithsonian Institution ISSN 1056-6805 Editor: Carlo M. Borden Associate Editor: Peter Seitel Director of Design: Kristen Fernekes Graphic Designer: Caroline Brownell Design Assistant: Rachele Rileu The Silk Road: Connecting Cultures. Creating Trust at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival is a partnership of the Smithsonian Institution Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and the Silk Road Project. Inc. The Festival site is designed by Rajeev Sethi Scenographers and produced in cooperation with the Asian Heritage Foundation. The Festival is co-sponsored by the National Park Service. *W* Smithsonian Folklife Festival !SILKR®AD *4/>V project The Festival is supported by federally appropriated funds. Smithsonian trust funds, contributions from governments, businesses, foundations, and individuals, in-kind assistance, volunteers, food and craft sales, and Friends of the Festival. The 2002 Festival has been made possible through the following generous sponsors and donors to the Silk Road Project. Inc. LEAD FUNDER AND KEY CREATIVE PARTNER GLOBAL CORPORATE PARTNERS_ FOUNDING SUPPORTER MAJOR FUNDING BY Sony Classical The Starr Foundation Mr. and Mrs. Henry R. Kravis Mr. -

People of Reliable Loyalty…

Muftiates and the State in Modern Russia the State in Modern Muftiates and loyalty… People of reliable This dissertation presents a full-fledged portrait of the muftiate (spiritual administration of Muslims) in modern Russia. Designed initially for the purpose PEOPLE OF RELIABLE LOYALTY… of controlling religious activity, over time the institution of the muftiate was appropriated by Muslims and became a key factor in preserving national identity Muftiates and the State in Modern Russia for different ethnic groups of Tatars. In modern Russia numerous muftiates play the controversial role of administrative bodies responsible for the enforcement RENAT BEKKIN of some aspects of domestic and foreign policy on behalf of the state. Bekkin’s research focuses on muftiates in the European part of Russia, examining both their historical development and their functioning in the modern context. The analysis draws on academic literature, written and oral texts produced by the ministers of the Islamic religion, and archival sources, as well as numerous interviews with current and former muftis and other Islamic bureaucrats. Basing himself in the theory of the economics of religion, the author treats Russian muftiates as firms competing in the Islamic segment of the religious market. He applies economic principles in analyzing how the muftiates interact with each other, with other religious organizations in Russia, and with the Russian state. The author provides his own classification of muftiates in Russia, depending on the role they play in the religious market. Renat Bekkin is a religious studies scholar at Södertörn University. He holds two Russian degrees: Doctor of Sciences in Economics, and Candidate of Sciences in Law.