GHR Full Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legends in Concert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 31, 2020 CONTACT: DeAnn Lubell-Ames – (760) 831-3090 Note: Photos available at http://mccallumtheatre.com/index.php/media Legends In Concert: The Divas Tributes To Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston And Aretha Franklin McCallum Theatre Thursday – February 27 – 3:00 Pm And 8:00pm Palm Desert, CA – Through the generosity of Harold Matzner, the McCallum Theatre presents Legends in Concert—The Divas, featuring tributes to Barbra Streisand, Celine Dion, Whitney Houston and Aretha Franklin, for two shows: at 3:00pm and 8:00pm, Thursday, Feb. 27. Legends in Concert is the longest-running show in Las Vegas history, and after 35 years is still voted the No. 1 tribute show in the city. The internationally acclaimed and award-winning production is known as the pioneer of live tribute shows, and possesses the greatest collection of live tribute artists in the world. These incredible artists have pitch-perfect live vocals, signature choreography, and stunningly similar appearances to the legends they portray. Jazmine (Whitney Houston) draws her musical inspiration from her Cuban heritage while speaking and singing in both English and Spanish. After deciding to pursue her music career on the European music scene, she earned immediate success. After signing a one-album deal with Finland's K-TEL Records, Jazmine's first single achieved international success: In January 1996, "Love Like Never Before" rose to No. 1 on the French dance chart, dropping Madonna to No. 2 and passing same-week entries from Michael Jackson, Bon Jovi and Whitney Houston. She has appeared on the WB television show Pop Stars and on several episodes of the Dick Clark Productions show Your Big Break. -

MERLE HAGGARD After Beating Lung Cancer, “The Hag” Still Is Who He Is

MAY 2010 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM Q&A Travis Huggitt Travis MERLE HAGGARD After beating lung cancer, “The Hag” still is who he is MERLE HAGGARD’S NEW ALBUM is lot of young musicians now. Everything I come to the top. I didn’t used to have to called I Am What I Am, but that title could has changed. worry about things like that. have been affi xed to almost anything he’s recorded during his nearly half-century What are some of those changes? Has it made you a better singer? as one of America’s most stubbornly The methods of recording have changed I’ll have to leave that to the critics and to the self-possessed singers and songwriters. quite a bit. They’ve got it now where if you audience. In my own opinion, I think it’s made He has built a body of work unequaled can get somewhere in the general area of a better singer of me. in the country genre, one created on the right pitch they can bring you into key clear-eyed slice-of-life classics like “Okie with an electronic manipulative device. But Does the new album’s peaceful From Muskogee,” “Hungry Eyes,” “I’m a we still do our recordings the same way we tone refl ect how you feel about your Lonesome Fugitive” and “Mama Tried.” did ’em 30 years ago. We still go to tape. We life now? I Am What I Am is his fi rst album since being have a 24-track board and mix things down I’m doing probably as good as a guy my treated for lung cancer in 2008, causing a from that. -

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

Deana Carter Danny Myrick

Deana Carter DEANA CARTER, the daughter of famed studio guitarist and producer Fred Carter, Jr., grew up surrounded by musical greats, including Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Waylon Jennings, and Simon & Garfunkel. She developed her songwriting skills at writer’s nights throughout Nashville, but her real break came when one of her demo tapes fell into the hands of Willie Nelson, who remembered Deana as a child. Impressed with how she’d grown as a songwriter, Nelson asked Deana to perform along with John Mellencamp, Kris Kristofferson, and Neil Young, as the only female solo artist to appear at Farm Aid VII in 1994. Her 1996 debut album Did I Shave My Legs for This? quickly climbed to the top of both the country and pop charts, quickly achieving multi-platinum status. "Strawberry Wine,” the first single from the album, was awarded CMA's 1997 Single of the Year. Seven albums and a decade later, Deana is still writing and producing for both the pop/rock and country markets when not on the road touring. Her superstar success continues to be evident. Her chart topper “You & Tequila,” co-written with Matraca Berg and recorded by Kenny Chesney, was nominated in 2011 as CMA’s “Song of the Year” and received two Grammy nods. Carter also recently co-wrote and produced a new album for recording artist Audra Mae while putting the finishing touches on her own Southern Way of Life that hit the shelves last December. Danny Myrick DANNY MYRICK is an award winning songwriter and musician based here in Nashville. -

TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 Cds for $10 Each!

THOMAS FRASER I #79/168 AUGUST 2003 REVIEWS rQr> rÿ p rQ n œ œ œ œ (or not) Nancy Apple Big AI Downing Wayne Hancock Howard Kalish The 100 Greatest Songs Of REAL Country Music JOHN THE REVEALATOR FREEFORM AMERICAN ROOTS #48 ROOTS BIRTHS & DEATHS s_________________________________________________________ / TMRU BESTSELLER!!! SCRAPPY JUD NEWCOMB'S "TURBINADO ri TEXAS ROUND-UP YOUR INDEPENDENT TEXAS MUSIC SUPERSTORE Buy 5 CDs for $10 each! #1 TMRU BESTSELLERS!!! ■ 1 hr F .ilia C s TUP81NA0Q First solo release by the acclaimed Austin guitarist and member of ’90s. roots favorites Loose Diamonds. Scrappy Jud has performed and/or recorded with artists like the ' Resentments [w/Stephen Bruton and Jon Dee Graham), Ian McLagah, Dan Stuart, Toni Price, Bob • Schneider and Beaver Nelson. • "Wall delivers one of the best start-to-finish collections of outlaw country since Wayton Jennings' H o n k y T o n k H e r o e s " -Texas Music Magazine ■‘Super Heroes m akes Nelson's" d e b u t, T h e Last Hurrah’àhd .foltowr-up, üflfe'8ra!ftèr>'critieat "Chris Wall is Dyian in a cowboy hat and muddy successes both - tookjike.^ O boots, except that he sings better." -Twangzirtc ;w o tk s o f a m e re m o rta l.’ ^ - -Austin Chronlch : LEGENDS o»tw SUPER HEROES wvyw.chriswatlmusic.com THE NEW ALBUM FROM AUSTIN'S PREMIER COUNTRY BAND an neu mu - w™.mm GARY CLAXTON • acoustic fhytftm , »orals KEVIN SMITH - acoustic bass, vocals TON LEWIS - drums and cymbals sud Spedai td truth of Oerrifi Stout s debut CD is ContinentaUVE i! so much. -

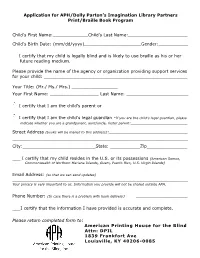

Application for APH/Dolly Parton's Imagination Library Partners

Application for APH/Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library Partners Print/Braille Book Program Child’s First Name:_____________Child’s Last Name:______________________ Child’s Birth Date: (mm/dd/yyyy)_____________________Gender:___________ I certify that my child is legally blind and is likely to use braille as his or her future reading medium. Please provide the name of the agency or organization providing support services for your child: _____________________________________________________ Your Title: (Mr./ Ms./ Mrs.) _________________ Your First Name: __________________ Last Name: _______________________ I certify that I am the child’s parent or I certify that I am the child's legal guardian *If you are the child’s legal guardian, please indicate whether you are a grandparent, aunt/uncle, foster parent:_____________________ Street Address (books will be mailed to this address):_____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ City:___________________________State: ___________Zip_______________ ___ I certify that my child resides in the U.S. or its possessions (American Samoa, Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, U.S. Virgin Islands) Email Address: (so that we can send updates) _________________________________________________________________ Your privacy is very important to us. Information you provide will not be shared outside APH. Phone Number: (In case there is a problem with book delivery) ________________________ ___I certify that the information I have provided is accurate and complete. Please return completed form to: American Printing House for the Blind Attn: DPIL 1839 Frankfort Ave Louisville, KY 40206-0085 Thank you for your application! If your child is eligible and we enroll him or her in the APH/DPIL Partners Print/Braille Book Program, you will be emailed a welcome letter from Dolly Parton and APH within 10 business days. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Narrative Representations of Gender and Genre Through Lyric, Music, Image, and Staging in Carrie Underwood’S Blown Away Tour

COUNTRY CULTURE AND CROSSOVER: Narrative Representations of Gender and Genre Through Lyric, Music, Image, and Staging in Carrie Underwood’s Blown Away Tour Krisandra Ivings A Thesis Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Master of Arts in Music with Specialization in Women’s Studies University of Ottawa © Krisandra Ivings, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 Abstract This thesis examines the complex and multi-dimensional narratives presented in the work of mainstream female country artist Carrie Underwood, and how her blending of musical genres (pop, rock, and country) affects the narratives pertaining to gender and sexuality that are told through her musical texts. I interrogate the relationships between and among the domains of music, lyrics, images, and staging in Underwood’s live performances (Blown Away Tour: Live DVD) and related music videos in order to identify how these gendered narratives relate to genre, and more specifically, where these performances and videos adhere to, expand on, or break from country music tropes and traditions. Adopting an interlocking theoretical approach grounded in genre theory, gender theory, narrative theory in the context of popular music, and happiness theory, I examine how, as a female artist in the country music industry, Underwood uses genre-blending to construct complex gendered narratives in her musical texts. Ultimately, I find that in her Blown Away Tour: Live DVD, Underwood uses diverse narrative strategies, sometimes drawing on country tropes, to engage techniques and stylistic influences of several pop and rock styles, and in doing so explores the gender norms of those genres. ii Acknowledgements A great number of people have supported this thesis behind the scenes, whether financially, academically, or emotionally. -

This Week, Purely out of Curiosity, I Looked up Rolling Stones Top 100 Songwriters of All Time. a Few Spots on the List Surpris

This week, purely out of curiosity, I looked up Rolling Stones top 100 songwriters of all time. A few spots on the list surprised me a little but let’s see if you agree with their ordering. I’m not going to read all 100, but I’ll hit a few of the names that we are familiar with today. 97 Taylor Swift 95 Bee gees 91 Eminem 84 Kanye 82 Marvin Gaye 76 Loretta Lynn 69 James Taylor 68 Jay Z 60 Willie Nelson 59 Tom Petty 56 Madonna 54 Kurt Cobain 53 Stevie Nicks 50 Billie Joel 48 Elton John 47 Neil Diamond 43 Johnny Cash 40 John Fogerty 39 David Bowie 35 Bono and the Edge 34 Michael Jackson 33 Merle Haggard 31 Dolly Parton (3000 songs, 20 country #1) 29 Buddy Holly 26 James Brown 22 Van Morrison 18 Prince 16 Leonard Cohen 14 Bruce Springsteen 12 Brian Wilson 11 Bob Marley 10 Stevie Wonder 9 Joni Mitchell 8 Paul Simon 7 Carole King and Gerry Goffin (Wrote music for the Beatles, Dianna Ross, Whitney Houston, Gladys Night and the pips) 6 Mick Jagger and Keith Richards 5 Smokey Robinson 4 Chuck Berry 3 John Lennon 2 Paul McCartney 1 Bob Dylan These are the people who write the score that lays behind the scenes of most of our lives. I’m one of those people who gets overwhelmed with nostalgia anytime a song from my early years comes on the radio. My wife on the other hand grew up weirdly sheltered. We have this pattern that we have probably played out 1,000 times in our marriage where an old song will come on and I immediately start to sing along and I’ll look Esther right in her eyes and sing the rest of the line like I’m an 80s rock star and she’s my groupie and the look that she returns to me is so blank that I almost feel the need to introduce myself to make sure she hasn’t forgotten who I am. -

Emmylou Harris and Rodney Crowell the Traveling Kind

Titelliste der Sendung “Country Special” vom 31.5.2015 EMMYLOU HARRIS AND RODNEY CROWELL THE TRAVELING KIND GRAM PARSONS/EMMYLOU HARRIS BRAND NEW HEARTACHE EMMYLOU HARRIS AND RODNEY CROWELL IF YOU LIVED HERE, YOU'D BE HOME BY NOW DOLLY PARTON/L. RONSTADT/EMMYLOU HARRIS WILDFLOWERS EMMYLOU HARRIS AND RODNEY CROWELL NO MEMORIES HANGING 'ROUND ROSANNE CASH WHEN THE MASTER CALLS THE ROLL EMMYLOU HARRIS AND RODNEY CROWELL BRING IT ON HOME TO MEMPHIS LUCINDA WILLIAMS I JUST WANTED TO SEE YOU SO BAD DOUG SEEGERS/EMMYLOU HARRIS SHE NORAH JONES IF THE LAW DON'T WANT YOU EMMYLOU HARRIS AND RODNEY CROWELL JUST PLEASING YOU MARK KNOPFLER/EMMYLOU HARRIS RED STAGGERWING EMMYLOU HARRIS AND RODNEY CROWELL YOU CAN'T SAY WE DIDN'T TRY SOLOMON BURKE/EMMYLOU HARRIS WE'RE GONNA HOLD ON EMMYLOU HARRIS/DON WILLIAMS IF I NEEDED YOU WILLIE NELSON AND MERLE HAGGARD IT'S ALL GOING TO POT WILLIE NELSON AND MERLE HAGGARD DJANGO AND JIMMIE JIMMIE RODGERS WAITING FOR A TRAIN BOB DYLAN MY BLUE EYED JANE WILLIE NELSON AND MERLE HAGGARD DON'T THINK TWICE, IT'S ALRIGHT ROSIE FLORES GIRL HAGGARD WILLIE NELSON AND MERLE HAGGARD UNFAIR WEATHER FRIEND BRUCE ROBISON WHAT WOULD WILLIE DO WILLIE NELSON AND MERLE HAGGARD/BOBBY BARE MISSING OL' JOHNNY CASH DJANGO REINHARDT NUAGES WILLIE NELSON AND MERLE HAGGARD ALICE IN HULALAND ASLEEP AT THE WHEEL/OLD CROW MEDICINE SHOW TIGER RAG POKEY LAFARGE SOMETHING IN THE WATER B.B. KING/WILLIE NELSON NIGHT LIFE WILLIE NELSON AND MERLE HAGGARD THE ONLY MAN WILDER THAN ME . -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

“Mama Tried”--Merle Haggard (1968) Added to the National Registry: 2015 Essay by Rachel Rubin (Guest Post)*

“Mama Tried”--Merle Haggard (1968) Added to the National Registry: 2015 Essay by Rachel Rubin (guest post)* “Mama Tried” original LP cover When Merle Haggard released “Mama Tried” in 1968, it quickly became his biggest hit. But, although in terms of broad reception, the song would be shortly eclipsed by the controversies surrounding Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” (released the next year), “Mama Tried” was a path-breaking song in several significant ways. It efficiently marked important, shaping changes to country music made by the generation of musicians and audiences who came of age post-World War II (as did Haggard, who born in 1937). “Mama Tried,” then, encompasses and articulates developments of both Haggard’s career and artistic focus, and the direction of country music in general. Indeed, Haggard’s own story usefully traces the trajectory of modern country music. Haggard was born near the city of Bakersfield, California, in a converted boxcar. He was born two years after his parents, who were devastated Dust Bowl “Okies,” traveled there from East Oklahoma as part of the migration most famously represented by John Steinbeck in “Grapes of Wrath” (1939)--an important novel that presented and commented on the class-based contempt that “Okies” faced in California. Haggard confronted this contempt throughout his career (and even after his 2016 death, the class- based contempt continues). His family (including Haggard himself) took up a range of jobs, including agricultural work, truck-driving, and oil-well drilling. Labor remained a defining factor of Haggard’s music until he died in 2016, and he frequently found ways to refer to his musicianship as work (making a sharp joke on an album, for instance, about the connection between picking cotton and picking guitar).