Philip Kennedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aberdeenshire)

The Mack Walks: Short Walks in Scotland Under 10 km Forvie Reserve-Hackley Bay Ramble (Aberdeenshire) Route Summary This walk offers a variety of environments: heath-land; rocky sea- cliffs; an isolated sandy cove; capped of with a visit to the pretty former fishing village of Collieston. The distance covered, and overall ascent, is moderate, and should suit walkers of all abilities. Duration: 2.75 hours. Route Overview Duration: 2.75 hours. Transport/Parking: The nearest public transport is the Stagecoach bus service that passes through Cruden Bay. Check timetable. It would be a 2 km walk from your drop-off point on the A975 to the start of the walk. There is a car-park at the start of the walk at the Forvie Visitor Centre. Length: 7.550 km / 4.72 mi Height Gain: 145 meter Height Loss: 145 meter Max Height: 46 meter Min Height: 0 meter Surface: Moderate. Mostly on good paths. Some sections may be muddy after wet weather. Child Friendly: Yes, if children are used to walks of this distance and overall ascent. Difficulty: Medium. Dog Friendly: Yes. On lead on public roads and near to any farm livestock. Refreshments: The Smuggler’s Cone cafe/ice cream vendor near the beach in Collieston. Closed during winter months. Open at weekends in summer months, every day during summer school holidays. Otherwise, Briggies (Newburgh Inn) in Newburgh, or The Barn cafe in Foveran. Description This is a pleasant and varied ramble in the Forvie National Nature Reserve, through the wild coastal heath-land of Forvie Moor, meeting impressive cliffs that lead to an isolated and pristine bay beneath Hackley Head. -

24 Sedimentology of the Ythan Estuary, Beach and Dunes, Newburgh Area

24 SEDIMENTOLOGY OF THE YTHAN ESTUARY, BEACH AND DUNES, NEWBURGH AREA N. H. TREWIN PURPOSE The object of the excursion is to examine recent sedimentological features of the Ythan estuary and adjacent coast. Sedimentary environments include sheltered estuarine mud flats, exposed sandy beach and both active and stabilised wind blown sand dunes. Many of the sedimentary features to be described are dependent on local effects of tides, winds and currents. The features described are thus not always present, and the area is worth visiting under different weather conditions particularly during winter. ACCESS Most of the area described lies within the Sands of Forvie National Nature Reserve and all notices concerning access must be obeyed, particularly during the nesting season of terns and eider ducks (Apr.-Aug.) when no access is possible to some areas. Newburgh is 21 km (13 miles) north of Aberdeen via the A92 and the A975. Parking for cars is available at the layby by locality 1 at [NK 006 2831], and on the east side of Waterside Bridge for localities 2-8 (Fig. 1). Alternatively the area can be reached by a cliff top path from The Nature Reserve Centre at Collieston and could be visited in conjunction with Excursion 13. Localities 9- 10 can be reached from the beach car park at [NK 002 247] at the end of the turning off the A975 at the Ythan Hotel. There is a single coach parking space at the parking area at Waterside bridge, but the other parking areas are guarded by narrow entrances to prevent occupation by travellers with caravans. -

Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies

1 From mountain to sea Aberdeenshirep Support Directory for Families, Authority Staff and Partner Agencies December 2017 2 | Contents 1 BENEFITS 3 2 CHILDCARE AND RESPITE 23 3 COMMUNITY ACTION 43 4 COMPLAINTS 50 5 EDUCATION AND LEARNING 63 6 Careers 81 7 FINANCIAL HELP 83 8 GENERAL SUPPORT 103 9 HEALTH 180 10 HOLIDAYS 194 11 HOUSING 202 12 LEGAL ASSISTANCE AND ADVICE 218 13 NATIONAL AND LOCAL SUPPORT GROUPS (SPECIFIC CONDITIONS) 223 14 SOCIAL AND LEISURE OPPORTUNITIES 405 15 SOCIAL WORK 453 16 TRANSPORT 458 SEARCH INSTRUCTIONS 1. Right click on the document and select the word ‘Find’ (using a left click) 2. A dialogue box will appear at the top right hand side of the page 3. Enter the search word to the dialogue box and press the return key 4. The first reference will be highlighted for you to select 5. If the first reference is not required, return to the dialogue box and click below it on ‘Next’ to move through the document, or ‘previous’ to return 1 BENEFITS 1.1 Advice for Scotland (Citizens Advice Bureau) Information on benefits and tax credits for different groups of people including: Unemployed, sick or disabled people; help with council tax and housing costs; national insurance; payment of benefits; problems with benefits. http://www.adviceguide.org.uk 1.2 Attendance Allowance Eligibility You can get Attendance Allowance if you’re 65 or over and the following apply: you have a physical disability (including sensory disability, e.g. blindness), a mental disability (including learning difficulties), or both your disability is severe enough for you to need help caring for yourself or someone to supervise you, for your own or someone else’s safety Use the benefits adviser online to check your eligibility. -

ADDRESSING CONCERNS RAISED by RSPB SCOTLAND .88 27 Addressing Concerns Raised by RSPB Scotland

Annex B - Appropriate Assessment – Moray West Offshore Wind Farm T: +44 (0)300 244 5046 E: [email protected] SCOTTISH MINISTERS ASSESSMENT OF THE PROJECT’S IMPLICATIONS FOR DESIGNATED SPECIAL AREAS OF CONSERVATION (“SAC”), SPECIAL PROTECTION AREAS (“SPA”) AND PROPOSED SPECIAL PROTECTION AREAS (“pSPA”) IN VIEW OF THE SITES’ CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES APPLICATION FOR CONSENT UNDER SECTION 36 OF THE ELECTRICITY ACT 1989 (AS AMENDED) AND FOR MARINE LICENCES UNDER THE MARINE (SCOTLAND) ACT 2010 AND MARINE AND COASTAL ACCESS ACT 2009 FOR THE CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF THE MORAY WEST OFFSHORE WIND FARM AND ASSOCIATED OFFSHORE TRANSMISSION INFRASTRUCTURE SITE DETAILS: MORAY WEST OFFSHORE WIND FARM AND EXPORT CABLE CORRIDOR BOUNDARY – APPROXIMATELY 22.5KM EAST OF THE CAITHNESS COASTLINE IN THE OUTER MORAY FIRTH Name Assessor or Approver Date Fiona Mackintosh Assessor 15 April 2019 Ross Culloch Assessor 15 April 2019 Tom Evans Assessor 15 April 2019 Gayle Holland Approver 26 April 2019 Annex B - Appropriate Assessment – Moray West Offshore Wind Farm TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: BACKGROUND ..................................................................................... 2 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 2 2 Appropriate assessment (“AA”) conclusion ................................................................ 2 3 Background to including assessment of proposed SPAs ........................................... 3 4 Details of proposed operation -

List of Consultees and Issues.Xlsx

Name / Organisation Issue Mr Ian Adams Climate change Policy C1 Using resources in buildings Mr Ian Adams Shaping Formartine Newburgh Mr Iain Adams Natural Heritage and Landscape Policy E2 Landscape Mr Ian Adams Shaping Formartine Newburgh Mr Michael Adams Natural Heritage and Landscape Policy E2 Landscape Ms Melissa Adams Shaping Marr Banchory Ms Faye‐Marie Adams Shaping Garioch Blackburn Mr Iain Adams Shaping Marr Banchory Michael Adams Natural Heritage and Landscape Policy E2 Landscape Ms Melissa Adams Natural Heritage and Landscape Policy E2 Landscape Mr Michael Adams Shaping Marr Banchory Mr John Agnew Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Stonehaven Mr John Agnew Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Stonehaven Ms Ruth Allan Shaping Banff and Buchan Cairnbulg and Inverallochy Ruth Allan Shaping Banff and Buchan Cairnbulg and Inverallochy Mrs Susannah Almeida Shaping Banff and Buchan Banff Ms Linda Alves Shaping Buchan Hatton Mrs Michelle Anderson Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Luthermuir Mr Murdoch Anderson Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Luthermuir Mrs Janette Anderson Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Luthermuir Miss Hazel Anderson Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Luthermuir J Angus Shaping Banff and Buchan Cairnbulg and Inverallochy Mrs Eeva‐Kaisa Arter Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Mill of Uras Mrs Eeva‐Kaisa Arter Shaping Kincardine and Mearns Mill of Uras Mr Robert Bain Shaping Garioch Kemnay K Baird Shaping Banff and Buchan Cairnbulg and Inverallochy Rachel Banks Shaping Formartine Balmedie Mrs Valerie Banks Shaping Formartine Balmedie Valerie Banks -

The Dalradian Rocks of the North-East Grampian Highlands of Scotland

Revised Manuscript 8/7/12 Click here to view linked References 1 2 3 4 5 The Dalradian rocks of the north-east Grampian 6 7 Highlands of Scotland 8 9 D. Stephenson, J.R. Mendum, D.J. Fettes, C.G. Smith, D. Gould, 10 11 P.W.G. Tanner and R.A. Smith 12 13 * David Stephenson British Geological Survey, Murchison House, 14 West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 15 [email protected] 16 0131 650 0323 17 John R. Mendum British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 18 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 19 Douglas J. Fettes British Geological Survey, Murchison House, West 20 Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA. 21 C. Graham Smith Border Geo-Science, 1 Caplaw Way, Penicuik, 22 Midlothian EH26 9JE; formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 23 David Gould formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 24 P.W. Geoff Tanner Department of Geographical and Earth Sciences, 25 University of Glasgow, Gregory Building, Lilybank Gardens, Glasgow 26 27 G12 8QQ. 28 Richard A. Smith formerly British Geological Survey, Edinburgh. 29 30 * Corresponding author 31 32 Keywords: 33 Geological Conservation Review 34 North-east Grampian Highlands 35 Dalradian Supergroup 36 Lithostratigraphy 37 Structural geology 38 Metamorphism 39 40 41 ABSTRACT 42 43 The North-east Grampian Highlands, as described here, are bounded 44 to the north-west by the Grampian Group outcrop of the Northern 45 Grampian Highlands and to the south by the Southern Highland Group 46 outcrop in the Highland Border region. The Dalradian succession 47 therefore encompasses the whole of the Appin and Argyll groups, but 48 also includes an extensive outlier of Southern Highland Group 49 strata in the north of the region. -

The STATE of the EAST GRAMPIAN COAST

The STATe OF THE eAST GRAMPIAN COAST AUTHOR: EMILY HASTINGS ProjEcT OffIcer, EGcP DEcEMBER 2009 The STATe OF THE eAST GRAMPIAN COAST AUTHOR: EMILY HASTINGS ProjEcT OffIcer, EGcP DEcEMBER 2009 Reproduced by The Macaulay Land Use Research Institute ISBN: 0-7084-0675-0 for further information on this report please contact: Emily Hastings The Macaulay Land Use Research Institute craigiebuckler Aberdeen AB15 8QH [email protected] +44(0)1224 395150 Report should be cited as: Hastings, E. (2010) The State of the East Grampian coast. Aberdeen: Macaulay Land Use Research Institute. Available from: egcp.org.uk/publications copyright Statement This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of The Macaulay Land Use Research Institute. The views expressed by the author (s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of The Macaulay Land Use Research Institute. © MLURI 2010 THE MACAULAY LAND USE RESEARCH INSTITUTE The STATe OF THE eAST GRAMPIAN COAST CONTeNTS A Summary Of Findings i 1 introducTIoN 1 2 coastal management 9 3 Society 15 4 EcoNomy 33 5 envIronment 45 6 discussioN and coNcLuSIons 97 7 rEfErences 99 AppendIx 1 – Stakeholder Questionnaire 106 AppendIx 2 – Action plan 109 The STATe OF THE eAST GRAMPIAN COAST A Summary of Findings This summary condenses the findings of the State of the East Grampian coast report into a quick, user friendly tool for gauging the state or condition of the aspects and issues included in the main report. The categories good, satisfactory or work required are used as well as a trend where sufficient data is available. -

The Soils of the Country Round Banchory, Stonehaven and Forfar (Sheets 66/67 – Banchory & Stonehaven and 57 – Forfar)

Memoirs of the Soil Survey of Scotland The Soils of the Country round Banchory, Stonehaven and Forfar (Sheets 66/67 – Banchory & Stonehaven and 57 – Forfar) By R. Glentworth, J.C.C. Romans, D. Laing, B.M. Shipley and E.L. Birse (Ed. J.S. Bell) The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen 2016 Contents Chapter Page Preface v Acknowledgements v 1. Description of the Area 1 Location and Extent 1 Physical Features 1 2. Climate 8 3. Geology and Soil Parent Materials 17 Solid Geology 17 Superficial Deposits 19 Parent Materials 20 4. Soil Formation, Classification and Mapping 27 Soil Formation 27 Soil Classification 31 Soil Mapping 36 5. Soils Introduction 37 Auchenblae Association 40 Auchenblae Series 40 Candy Series 41 Balrownie Association 42 Balrownie Series 44 Aldbar Series 47 Lour Series 49 Findowrie Series 51 Skeletal Soils 51 Boyndie Association 51 Boyndie Series 51 Anniston Series 52 Dallachy Series 53 Collieston Association 54 Cairnrobin Series 54 Collieston Series 55 Marshmire Series 56 Corby Association 56 Kinord Series 57 Corby Series 59 Leys Series 60 i Mulloch Series 60 Mundurno Series 61 Countesswells Association 62 Raemoir Series 64 Countesswells Series 65 Dess Series 66 Charr Series 67 Terryvale Series 69 Strathgyle Series 70 Drumlasie Series 72 Skeletal Soils 73 Deecastle Association 73 Deecastle Series 73 Dinnet Association 75 Dinnet series 75 Oldtown Series 77 Maryfield Series 78 Ferrar Series 79 Forfar Association 81 Vinny Series 82 Forfar Series 84 Vigean Series 87 Laurencekirk Association 89 Drumforber Series 90 Oldcake Series -

Formartine Area Bus Forum

FORMARTINE AREA BUS FORUM MINUTES OF MEETING ON MONDAY 9TH NOVEMBER 2015 THEATRE, ELLON COMMUNITY CAMPUS, ELLON In Attendance Councillor R. J. Merson (Aberdeenshire Council) (Chair) Councillor P. Johnston (Aberdeenshire Council) Kaye Cowie (Meldrum and Bourtie Community Council) Stanley Glennie (Meldrum and Bourtie Community Council) Kevin Glennie (Meldrum and Bourtie Community Council) Debra Campbell (CPO, Aberdeenshire Council) Hilda Drummond (Bus User, Potterton) Sheila Morrison (Bus User, New Byth) Ethel McCurrach (Bus User, Turriff) Kathryn Morrison (Bus User, Ellon) Krista Wright (Bus User, Ellon) Lorna Owen (Bus User, Ellon) Sheila Noble (Bus User, Ellon) Sheila McKay (Bus User, Ellon) Jacquie Lafferty (Bus User, Ellon) Kenneth Gow (Bus User, Ellon) Chris Ramsey (Bus User, Collieston) Joe Cowan (Bus User, Balmedie) Ray Kenyon (Bus User, Newburgh) Anne Kenyon (Bus User, Newburgh) George Scott (Bus User) Sheila Scott (Bus User) John Carter (Bus User) M Jones (Bus User) Mark Fraser (Bus User) Tracey Fraser (Bus User) Dauna Matheson (Bus User) Yvonne Ferguson (Bus User) Doug Bain (Bain’s Coaches) Steve Walker (Managing Director, Stagecoach North Scotland) Neil Stewart (Principal Officer, Public Transport Unit, Aberdeenshire Council) Susan Watt (Senior Transport Officer, Public Transport Unit, Aberdeenshire Council) Apologies Councillor A. Robertson (Aberdeenshire Council) Councillor G. Owen (Aberdeenshire Council) Robert Martin (Bus User, Oldmeldrum) M. Hardy-Randall (Bus User, Newburgh) 1 1. Welcome and Introduction Councillor Merson welcomed everyone to the meeting and introductions were given. 2. Minutes of Meeting on 30 April 2015 It was raised from ‘the floor’ that Item 13.4. Page 9 was inaccurate as it was not confirmed at the meeting which services would serve Ellon Community Campus. -

Imposing C Listed Period Former Manse With

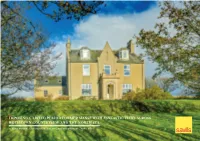

IMPOSING C LISTED PERIOD FORMER MANSE WITH FANTASTIC VIEWS ACROSS BOTH OPEN COUNTRYSIDE AND THE NORTH SEA slains house, collieston, ellon, aberdeenshire, ab41 8rt IMPOSING C LISTED PERIOD FORMER MANSE WITH FANTASTIC VIEWS ACROSS BOTH OPEN COUNTRYSIDE AND THE NORTH SEA slains house, collieston, ellon, aberdeenshire, ab41 8rt u Category C Listed 2½ storey former manse u Original manse built around 1876 by renowned Aberdeen City architect William Smith, famous for his involvement with Balmoral Castle in 1852 u Traditional features throughout, including original pine floorboards, deep skirtings, timber shutters, sash and case windows and decorative cornicing u Fantastic views over open countryside and down to Collieston beach, harbour and the North Sea u Great potential for multi-generational living or B&B/holiday lets u All bedrooms have the facilities available for wash hand basins to be installed, having previously operated as a bed and breakfast Entrance vestibule and cloakroom u Reception hall u Sitting room u Drawing room u Dining room u Breakfast room and kitchen u Walk in pantry u Utility room and workshop u Six double bedrooms and three bathrooms u Self-contained two- bedroom annexe, including a sitting room and shower room EPC = F Aberdeen: 16 miles Aberdeen International Airport: 20 miles Ellon: 6 miles Newburgh: 5 miles (All mileages are approximate) Collieston is a charming former fishing village, located on the North East coast of Scotland, between Cruden Bay and Newburgh. The village is nestled between the Forvie National Nature Reserve and the Coastal cliffs of Aberdeenshire. The Forvie reserve covers almost 1,000 hectares of sand dunes and dune heath between the North Sea and the estuary of the River Ythan. -

Directory for the City of Aberdeen

ABERDEEN CITY LIBRARIES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/directoryforcity185455uns DIRECTOR Y CITY OF ABERDEE N. 18 54-5 5, DIRECTORY FOR THE CITY OF ABERDEEN. 1854-55. TO WHICH IS ADDED, . Q THE NAMES OP THE PRINCIPAL INHABITANTS OF OLD ABERDEEN AND WOODSIDE. ABERDEEN \ WILLIAM BENNETT, PRINTER, No. 42, Castle Street. 1854. lU-^S- ®fc5. .3/. J+SS/t-. CONTENTS. Kalendar for 1854-55 Page 7 Agents for Insurance Companies 8 Section I.—Municipal Institutions 9 • II.—Commercial Establishments 11 Department, Customs, and Inland Revenue, v HI.—Post Office ™ 18 v IV.—Legal Department — 30 V.—Ecclesiastical Department . 32 ?J List of Vessels—Port of Aberdeen 33 Streets, Squares, Lanes, Courts, &c. and the Principal Inhabitants... 37 General Directory of the Inhabitants of the City of Aberdeen. 94 Old Aberdeen and Woodside „ Appendix i—viii 185 4. JULY. AUGUST. SEPTEMBEE. Sun. - 2 9 16 23 30 Sun. - 6 13 20 27 ... Sun. - 3 10 17 24 ... Mon. - 3 10 17 24 31 Mon. - 7 14 21 28 ... Mon. - 4 11 18 25 ... Tues.- 4 11 18 25 ... Tues.l 8 15 22 29 .. Tues.- 5 12 19 26 ... Wed. _ 5 12 19 26 ... Wed. 2 9 16 23 30 ... Wed. - 6 13 20 27 ... Thur.- 6 13 20 27 ... Thur. 3 10 17 24 31 ... Thur.- 7 14 21 28 ... Frid. - 7 14 21 28 ... Frid. 4 11 18 25 Frid. 1 8 15 22 29 ... Sat. 1 8 15 22 29 ... Sat. 5 12 19 26 Sat. -

Settlement Statements Formartine

SETTLEMENT STATEMENTS FORMARTINE APPENDIX – 279 – APPENDIX 8 FORMARTINE SETTLEMENT STATEMENTS CONTENTS BALMEDIE 281 NEWBURGH 326 BARTHOL CHAPEL 288 OLDMELDRUM 331 BELHEVIE 289 PITMEDDEN & MILLDALE 335 BLACKDOG 291 POTTERTON 338 COLLIESTON 295 RASHIERIEVE FOVERAN 340 CULTERCULLEN 297 ROTHIENORMAN 342 CUMINESTOWN 298 ST KATHERINES 344 DAVIOT 300 TARVES 346 ELLON 302 TIPPERTY 349 FINTRY 313 TURRIFF 351 FISHERFORD 314 UDNY GREEN 358 FOVERAN 315 UDNY STATION 360 FYVIE 319 WEST PITMILLAN 362 GARMOND 321 WOODHEAD 364 KIRKTON OF AUCHTERLESS 323 YTHANBANK 365 METHLICK 324 – 280 – BALMEDIE Vision Balmedie is a large village located roughly 5km north of Aberdeen, set between the A90 to the west and the North Sea coast to the east. The settlement is characterised by the woodland setting of Balmedie House and the long sand beaches of Balmedie Country Park. Balmedie is a key settlement in both the Energetica area and the Aberdeen to Peterhead strategic growth area (SGA). As such, Balmedie will play an important role in delivering strategic housing and employment allowances. In line with the vision of Energetica, it is expected that new development in Balmedie will contribute to transforming the area into a high quality lifestyle, leisure and global business location. Balmedie is expected to become an increasingly attractive location for development as the Aberdeen Western Peripheral Route reaches completion and decreases commuting times to Aberdeen. It is important that the individual character of the village is retained in the face of increased demand. The village currently has a range of services and facilities, which should be sustained during the period of this plan. In addition, the plan will seek to improve community facilities, including new health care provision.