Over a Barrel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catawba Island, the Great Peach Growing Center of Ohio from Sketches and Stories of the Lake Erie Islands, by Lydia J

Catawba Island, the Great Peach Growing Center of Ohio From Sketches and Stories of the Lake Erie Islands, by Lydia J. Ryall, American Publishers, Norwalk, OH, 1913 This reprint Copyright © 2003 by Middle Bass on the Web, Inc. "Why, and wherefore an island?" This question is usually the first formulated and put by the curiosity seeking stranger who approaches Catawba Island by stagecoach from Port Clinton - which, by the way, is the most available, and at certain seasons the only feasible, route thither. A trip to an island by stagecoach, instead of in a boat! The idea appears anomalous as it is novel: something similar to going to sea by rail, and, to discover how the thing is done, grows into a matter of keen interest as the observer progresses. His geography informs him that an island is “a body of land entirely surrounded with water”; and looking ahead - as the driver whips up his team - he vaguely wonders where, and how far along, the water lies, and how they are to get across it. Imagine, then, his complete surprise when, after a jaunt of several miles, the driver informs him that the mainland is already far behind, and that they are now on Catawba Island. Had the stranger turned back a few miles over the route, to a place where the two main thoroughfares, the “sand road,” and “lakeside” road, form a cross, or fork, he might have been shown a narrow ditch with an unpretentious bridge thrown across it. This ditch, terminating at the lake, is all that now serves to make Catawba an island. -

Growing Grapes in Missouri

MS-29 June 2003 GrowingGrowing GrapesGrapes inin MissouriMissouri State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University-Mountain Grove Growing Grapes in Missouri Editors: Patrick Byers, et al. State Fruit Experiment Station Missouri State University Department of Fruit Science 9740 Red Spring Road Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711-2999 http://mtngrv.missouristate.edu/ The Authors John D. Avery Patrick L. Byers Susanne F. Howard Martin L. Kaps Laszlo G. Kovacs James F. Moore, Jr. Marilyn B. Odneal Wenping Qiu José L. Saenz Suzanne R. Teghtmeyer Howard G. Townsend Daniel E. Waldstein Manuscript Preparation and Layout Pamela A. Mayer The authors thank Sonny McMurtrey and Katie Gill, Missouri grape growers, for their critical reading of the manuscript. Cover photograph cv. Norton by Patrick Byers. The viticulture advisory program at the Missouri State University, Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center offers a wide range of services to Missouri grape growers. For further informa- tion or to arrange a consultation, contact the Viticulture Advisor at the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center, 9740 Red Spring Road, Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711- 2999; telephone 417.547.7508; or email the Mid-America Viticulture and Enology Center at [email protected]. Information is also available at the website http://www.mvec-usa.org Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction.................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2 Considerations in Planning a Vineyard ........................................................ -

2014 Update on the Chloride Hydrogeochemistry in Seneca Lake, New York

A 2014 UPDATE ON THE CHLORIDE HYDROGEOCHEMISTRY IN SENECA LAKE, NEW YORK. John Halfman Department of Geoscience, Environmental Studies Program, Finger Lakes Institute Hobart & William Smith Colleges Geneva, NY 14456 [email protected] 12/10/2014 Introduction: Seneca Lake is the largest of the 11, elongated, north-south trending, Finger Lakes in central and western New York State (Fig. 1). It has a volume, surface area, watershed area, and maximum depth of 15.5 km3, 175 km2, 1,621 km2 (including Keuka watershed), and 188 m, respectively (Mullins et al., 1996). The lake basins were formed by glacial meltwaters eroding and deepening former stream valleys underneath the retreating Pleistocene Ice Sheet cutting into the Paleozoic sedimentary rocks approximately 10,000 years ago. Each basin was subsequently filled with a thick deposit of glacial tills and a thin veneer of pro-glacial lake clays. Basins not completely filled with sediment (e.g., Tully Valley), were subsequently filled with water and slowly accumulating postglacial muds. Seneca Lake is classified as a Class AA water resource by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYS DEC), except for a few locations along the shore (http://www.dec.ny.gov/regs/4592.html, Halfman et al., 2012). It supplies drinking water to approximately 100,000 people in the surrounding communities. Berg (1963) and Schaffner and Oglesby (1978) noted that chloride concentrations were significantly larger in Seneca Lake, and to a lesser extent in Cayuga Lake, than the other Finger Lakes. Wing et al. (1995) argued that the elevated chloride concentrations required an extra source of chloride beyond the measured fluvial fluxes to the lake. -

Kentucky Viticultural Regions and Suggested Cultivars S

HO-88 Kentucky Viticultural Regions and Suggested Cultivars S. Kaan Kurtural and Patsy E. Wilson, Department of Horticulture, University of Kentucky; Imed E. Dami, Department of Horticulture and Crop Science, The Ohio State University rapes grown in Kentucky are sub- usually more harmful to grapevines than Even in established fruit growing areas, ject to environmental stresses that steady cool temperatures. temperatures occasionally reach critical reduceG crop yield and quality, and injure Mesoclimate is the climate of the vine- levels and cause significant damage. The and kill grapevines. Damaging critical yard site affected by its local topography. moderate hardiness of grapes increases winter temperatures, late spring frosts, The topography of a given site, including the likelihood for damage since they are short growing seasons, and extreme the absolute elevation, slope, aspect, and the most cold-sensitive of the temperate summer temperatures all occur with soils, will greatly affect the suitability of fruit crops. regularity in regions of Kentucky. How- a proposed site. Mesoclimate is much Freezing injury, or winterkill, oc- ever, despite the challenging climate, smaller in area than macroclimate. curs as a result of permanent parts of certain species and cultivars of grapes Microclimate is the environment the grapevine being damaged by sub- are grown commercially in Kentucky. within and around the canopy of the freezing temperatures. This is different The aim of this bulletin is to describe the grapevine. It is described by the sunlight from spring freeze damage that kills macroclimatic features affecting grape exposure, air temperature, wind speed, emerged shoots and flower buds. Thus, production that should be evaluated in and wetness of leaves and clusters. -

Vol11-Issue02 Terroir and Other Myths of Winegrowing

Book Reviews 319 somebody like me who grew up with dry German Riesling, it was a great pleasure to read, but really, anybody interested in the story of dry Riesling will enjoy reading this book. Christian G.E. Schiller International Monetary Fund (ret.) and Emeritus Professor, University of Mainz, Germany [email protected] doi:10.1017/jwe.2016.24 MARK A. MATTHEWS: Terroir and Other Myths of Winegrowing. University of California Press, Oakland, 2016, 288 pp., ISBN 978-0-520-27695-6 (hardcover), $34.95. I immensely enjoyed reading this book, not so much because its author cites one of my articles, but mainly because he quotes Vladimir Nabokov, one of my favorite writers, who starts his Lolita with words that could apply to a wine when you taste it: “the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap at three on the teeth.” The preface sets the scene: “As I gained experience in the world of viticulture, I found that some of the received archetypes were incongruous with elementary crop science. For example, there is a long-standing argument that one cannot both irrigate vines and produce fine wines (yet rain and irrigation water are the same tograpevines)” (pp. ix–x). It is followed by four chapters debunking four false truths: (a) wine quality is determined by low yield and small berries; (b) vine balance is the key to fine wine grapes; (c) there is a critical ripening period, and vines should be stressed; and (d) terroir matters. I will try to deal fairly with all these issues, but it will come as no sur- prise to those who know me a bit if I spend more time on terroir. -

Croze Napa Valley PO Box 2679 Yountville, CA 94599 PH: 707.944.9247

Daniel Benton is the Vintner at Benton Family Wines (BFW) in Napa, California. Daniel was born and raised in Salisbury, North Carolina where much of his family still resides. He attended Catawba College and was a member of the 1996 conference champion football team. While attending Catawba, Daniel studied biology and chemistry, which ultimately led to his interest in wine production. Upon graduation, Daniel spent 10 years in corporate American before the romance of wine lured him away. After leaving his corporate post, he spent the next several years traveling wine regions and networking in the wine industry, eventually returning to school to obtain degrees in Viticulture and Enology. From there Daniel worked every aspect of the wine business from retail to distribution management, ultimately leading to wine production. From early mornings in the vineyard to harvest and fermentation in the winery, Daniel has been involved with every aspect of producing wine. As winemaker for Benton Family Wines, Daniel is responsible for all aspects of production, grower relations, and manages nationwide distribution for the company. BFW produces several wine brands with Croze Napa Valley being the flagship. With an emphasis on the production of wines that demonstrate balance and a European style, Croze distinguishes itself from many of its Napa neighbors. “Our philosophy is steeped in classic European tradition, and our wines have a profound sense of place. Vintages are meticulously handcrafted from vineyard to bottle, ensuring quality and recognizable style that is Croze.” Daniel, wife Kara, and son Callan work together with a talented staff to bring Croze wines to life each vintage. -

Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission

A LIMNOLOGICAL STUDY OF THE FINGER LAKES OF NEW YORK By Edward A. Birge and Chancey Juday Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey Madison, Wisconsin =========== ... _-_._._-_-----_... _---_.... _------=--__._.- Blank page retained for pagination CONTENTS. .:I- Page. Introduction. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 529 Methods and authorities. ................................................................ 530 Topography and hydrography of the Finger Lakes district. .. .. .. .. 532 General account. ...................................................................... 532 Lakes of the Seneca Basin " "", ,. .. .. 539 Seneca and Cayuga Lakes. .. .. .. .. .. .... .. .. .. .. .. .. .... .. .... .. .. .. ....... 539 Owasco Like " , .. .. 540 Keuka Lake....................... 540 Canandaigua Lake. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 54I Skaneateles Lake. .................................................................. 54I Otisco Lake. ...................................................................... 542 Lakes of the Genesee Basin...... .. .. .. ...... .. .... .. .. .. .. 543 Honeoye, Canadice, Hemlock, and Conesus Lakes. .. ....... 543 Temperatures " .. .. .. .. ... 546 General observations. ........ .. ........................................................ 546 Summer temperatures , .. .. .. 547 Surface and epilimnion ; ............................. 550 Thermocline... " ................................................. .. ............... 55I Hypolimnion. ...................................................................... 553 Winter temperatures -

PJ Wine, Inc. Catalog

PJ Wine, Inc. Catalog Generated 30th Sep 2021 S-00000730 Metaxa "5 Star" Brandy .750L $26.99 ACCESSORIES S-00000832 Metaxa "7 Star" Brandy .750L $32.99 S-00000516 Ocucaje Pisco Puro Quebranta (750ML) $21.99 Bag S-00000590 Pedro Domecq "Felipe II" Solera Sherry Brandy$20.99 .750L S-00000621 Pedro Domecq "Fundador" Solera Sherry Brandy$18.99 1.0L A01000 1 Bottle Holiday Gift Wrapping $7.00 S-00000463 Pedro Domecq "Presidente" Brandy 1.0L $23.99 A01001 2 Bottles Holiday Gift Wrapping $9.00 S-00000519 Romate "Solera Reserva" Brandy 1.0L $16.99 A01002 3 Bottles Holiday Gift Wrapping $11.00 S06135 Torres 10 Gran Reserva Brandy .750L $18.99 A00017 Gold 2 Bottle Wine Carrier $3.99 S00163 Torres Jaime I Reserva de la Familia Decanter .750L$129.99 A00025 PJ Wine Reusable 6 Bottles Wine Bag $2.99 CAN Gift Card S11369 High Noon Black Cherry Flavored Vodka & Soda$2.99 CAN (.355L) W-00003812 PJ WIne Gift Card - 100 Dollars $100.00 S11370 High Noon Grapefruit Flavored Vodka & Soda CAN$2.99 (.355L) W-00003813 PJ Wine Gift Card - 150 Dollars $150.00 S11952 High Noon Mango Flavored Vodka & Soda CAN$2.99 (.355L) W-00003814 PJ Wine Gift Card - 200 Dollars $200.00 S11371 High Noon Pineapple Flavored Vodka & Soda CAN$2.99 (.355L) W-00003808 PJ Wine Gift Card - 30 Dollars $30.00 S11372 High Noon Watermelon Flavored Vodka & Soda$2.99 CAN (.355L) W06233 PJ Wine Gift Card - 300 Dollars $300.00 S11380 Jose Cuervo Sparkling Paloma CAN (.200L) $2.69 W-00003810 PJ Wine Gift Card - 50 Dollars $50.00 S11381 Jose Cuervo Sparkling Rose Margarita CAN (.200L)$2.69 W-00003815 -

Ode to Catawba Wine “Written in Praise of Nicholas Longworth's Catawba Wine Made on the Banks of the Ohio River” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Circa 1857

Ode to Catawba Wine “Written In Praise of Nicholas Longworth's Catawba Wine Made on the Banks of the Ohio River” By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, circa 1857 Nicolas Longworth was a self-made millionaire and attorney who had an avid interest in horticulture. Beginning as early as 1813, he started vineyards along the banks of the Ohio River, hiring German immigrants whose homeland work was similar. He first began with a grape called “Alexander”, but found that it was only palatable as a fortified wine. He also planted “Catawba” vines and made a table wine which met with some success with the German immigrants in the area. An accidental discovery in the 1840’a led him to produce, with the later help of instruction from French winemakers on the “methode champenoise”, a sparkling Catawba wine – which met with great success both locally and on the East Coast. By the 1850’s, Longworth was producing 100,000 bottles of sparkling Catawba a year and advertising nationally. In the mid-1850’s he sent a case to poet, Henry Longfellow, then living in New York City, who wrote this ode. Remember, when Longfellow refers to the “Beautiful River”, he is referring to the Ohio River, which begins in Pittsburgh and passes through Cincinnati and Louisville, Kentucky on its way to Mississippi. Note to Readers: This poem is a great way to learn about grapes, rivers, and wine-making regions. To whit: Muscadine and Scuppernong, a type of Muscandine grape, are native southern American grapes with very thick green or bronze skins and frequently used in the South to made jam. -

A Review on Stems Composition and Their Impact on Wine Quality

molecules Review A Review on Stems Composition and Their Impact on Wine Quality Marie Blackford 1,2,* , Montaine Comby 1,2, Liming Zeng 2, Ágnes Dienes-Nagy 1, Gilles Bourdin 1, Fabrice Lorenzini 1 and Benoit Bach 2 1 Agroscope, Route de Duillier 50, 1260 Nyon, Switzerland; [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (Á.D.-N.); [email protected] (G.B.); [email protected] (F.L.) 2 Changins, Viticulture and Enology, HES-SO University of Applied Sciences and Arts Western Switzerland, Route de Duillier 50, 1260 Nyon, Switzerland; [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (B.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Often blamed for bringing green aromas and astringency to wines, the use of stems is also empirically known to improve the aromatic complexity and freshness of some wines. Although applied in different wine-growing regions, stems use remains mainly experimental at a cellar level. Few studies have specifically focused on the compounds extracted from stems during fermentation and maceration and their potential impact on the must and wine matrices. We identified current knowledge on stem chemical composition and inventoried the compounds likely to be released during maceration to consider their theoretical impact. In addition, we investigated existing studies that examined the impact of either single stems or whole clusters on the wine quality. Many parameters influence stems’ effect on the wine, especially grape variety, stem state, how stems are incorporated, Citation: Blackford, M.; Comby, M.; when they are added, and contact duration. Other rarely considered factors may also have an impact, Zeng, L.; Dienes-Nagy, Á.; Bourdin, G.; Lorenzini, F.; Bach, B. -

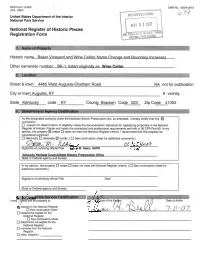

Baker Vineyard and Wine Cellar (Name Change

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior received mo 67? National Park Service m 3 1 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form iName of Propet^flSi _____ : Historic namp Rakpr Vinpyarrl anri Winp P.Allflr( Mamo Dhangp anH Rniinrlary Inrrpagp) Other name/site nnmhpr RK-1 ll.<;tpd originally a.<; Winp Hpllar Street & town 4465 West Augusta-Chatham Roa(d NA not for publication City or town Augusta, KY ___ X vicinity State Kentucky code KY County Bracken Code 023 Zip Code 41002 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^ nomination □ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ^ meets □ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant □ Nationally □ statewide I3 locally. {□ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) OS ZS Signature of certifying official/Title la M. Neary SHPO Data Kentucky Heritage Council/State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property □ meets □ does not meet the National Register criteria. (□ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certifying official/Title Date State or Federal agency and bureau I hereby c^ify that the property Is: Date of Action I entered in the National Register. □ See continuation sheet. > ll-o7 □ Determined eligible for the National Register □ See continuation sheet. -

President's Report

Page 1 December 2014 KLA Newsletter PROTECTING THE QUALITY OF THE LAKE www.keukalakeassoc.org Newsletter “Listen to the Lake” December2014 Kla membership PRESIDENT’S REPORT - Bill Laffin Renewal for 2015 This has been another great year for your Keuka Lake Membership renewal forms for Association as the Board of Directors has consistently 2015 will be sent out March1, worked to strengthen the resolve of “Protecting and Preserving Keuka 2015. To renew, you may return Lake”. The membership of the organization should have every confi- to the KLA office the enclosed dence that the group of volunteers that run the activities of the KLA form with your check or credit are totally committed to the lake and its watershed. As you will read in card info. You may also renew this newsletter, our activities continue to be diverse - ranging from on-line at our website with your educating our elected officials in Albany on the need to protect the wa- credit card. Whichever way you tershed from hydrofracking ; sampling water for quality indicators, choose to renew, please include publishing the KLA Directory and educating everyone on topic of any up-dated information,. Also Aquatic Invasive Species. The KLA was very fortunate to fund a grant you may select to receive our to Cornell Cooperative Extension of Yates County at mid-year for an monthly e-newsletter and e- Invasive Species Educator. Emily Staychock is doing a great job and announcements and choose to continues to enhance the KLA’s overall knowledge in this critical area. receive our quarterly newsletter I want to thank all of our members for your support and the confidence by e-mail, regular mail or both.