Soil Science, Development, and the Elusive Nature of Colombias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mothers in Science

The aim of this book is to illustrate, graphically, that it is perfectly possible to combine a successful and fulfilling career in research science with motherhood, and that there are no rules about how to do this. On each page you will find a timeline showing on one side, the career path of a research group leader in academic science, and on the other side, important events in her family life. Each contributor has also provided a brief text about their research and about how they have combined their career and family commitments. This project was funded by a Rosalind Franklin Award from the Royal Society 1 Foreword It is well known that women are under-represented in careers in These rules are part of a much wider mythology among scientists of science. In academia, considerable attention has been focused on the both genders at the PhD and post-doctoral stages in their careers. paucity of women at lecturer level, and the even more lamentable The myths bubble up from the combination of two aspects of the state of affairs at more senior levels. The academic career path has academic science environment. First, a quick look at the numbers a long apprenticeship. Typically there is an undergraduate degree, immediately shows that there are far fewer lectureship positions followed by a PhD, then some post-doctoral research contracts and than qualified candidates to fill them. Second, the mentors of early research fellowships, and then finally a more stable lectureship or career researchers are academic scientists who have successfully permanent research leader position, with promotion on up the made the transition to lectureships and beyond. -

Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus

Journal of Informetrics, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 1160-1177, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JOI.2018.09.002 Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: a systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories Alberto Martín-Martín1 , Enrique Orduna-Malea2 , Mike 3 1 Thelwall , Emilio Delgado López-Cózar Version 1.6 March 12, 2019 Abstract Despite citation counts from Google Scholar (GS), Web of Science (WoS), and Scopus being widely consulted by researchers and sometimes used in research evaluations, there is no recent or systematic evidence about the differences between them. In response, this paper investigates 2,448,055 citations to 2,299 English-language highly-cited documents from 252 GS subject categories published in 2006, comparing GS, the WoS Core Collection, and Scopus. GS consistently found the largest percentage of citations across all areas (93%-96%), far ahead of Scopus (35%-77%) and WoS (27%-73%). GS found nearly all the WoS (95%) and Scopus (92%) citations. Most citations found only by GS were from non-journal sources (48%-65%), including theses, books, conference papers, and unpublished materials. Many were non-English (19%- 38%), and they tended to be much less cited than citing sources that were also in Scopus or WoS. Despite the many unique GS citing sources, Spearman correlations between citation counts in GS and WoS or Scopus are high (0.78-0.99). They are lower in the Humanities, and lower between GS and WoS than between GS and Scopus. The results suggest that in all areas GS citation data is essentially a superset of WoS and Scopus, with substantial extra coverage. -

Royal Society, 1985

The Public Understanding of Science Report of a Royal Society adhoc Group endorsed by the Council of the Royal Society The Royal Society 6 Carlton House Terrace London SWlY 5AG CONTENTS Page Preface 5 Summary 6 1. Introduction 7 2. Why it matters 9 3. The present position 12 4. Formal education 17 5. The mass media 2 1 6. ' The scientific community 24 7. Public lectures, children's activities, museums and libraries 27 8. Industry 29 9. Conclusions and recommendations 31 Annexes A. List of those submitting evidence B. Visits and seminars C. Selected bibliography PREFACE This report was prepared by an ad hoc group under the chairmanship of Dr W.F. Bodmer, F.R.S.; it has been endorsed by the Council of the Royal Society. It deals with an issue that is important not only, or even mainly, for the scientific community but also for the nation as a whole and for each individual within it. More than ever, people need some understanding of science, whether they are involved in decision-making at a national or local level, in managing industrial companies, in skilled or semi-skilled employment, in voting as private citizens or in making a wide range of personal decisions. In publishing this report the Council hopes that it will highlight this need for an overall awareness of the nature of science and, more particularly, of the way that science and technology pervade modern life, and that it will generate both debate and decisions on how best they can be fostered. The report makes a number of recommendations. -

K-5 Specials & PE Handbook 2020-2021

K-5 Specials & PE Handbook 2020-2021 Table of Contents Contact Information PE Art STEM Computer Science Character Education Google Classroom Codes Specials Contact Information Physical Education: Mrs. Emiley Scales [email protected] Ms. Hideko Masuoka [email protected] Mrs. Ayesha Chubb [email protected] STEM: Ms. Kathryn Wiltrout [email protected] Art: Mrs. LeSha Martinez [email protected] Computer Science: Ms. Lauren Stanley [email protected] Character Education: Ms. Gergana Atanasova [email protected] Specials Rules: ❖ SAFETY first! This is our NUMBER ONE Rule ❖ RESPECT teachers and fellow classmates ❖ When the teacher is talking, everyone is listening ❖ Always use appropriate language (physical, verbal, digital) ❖ Keep hands and feet to yourself ❖ Respect your classmates, teachers space and property ❖ Follow directions the first time Unacceptable Behaviors: Consumption of food or chewing gum is not permitted, not following directions, disrespecting teachers and/or classmates, creating an unsafe environment for either themselves or their classmates. This applies to ALL Specials. Google Classroom ALL STUDENTS In order to ensure a smooth transition no matter what the school year brings, all classes will have access to Google Classroom. Each specials will have their own Google Classroom. Please make sure you are signing up for the correct classroom! Class codes can be found separated by grade level after the Specials Introductions. Google Classroom Procedures for Specials: Google Classroom will be the main digital platform we use. Please be sure to go to your assigned Special each day. Inside each google class is where you will find : ● Our Schedule ● Where we take attendance ● Links for live lessons via Zoom ● Links to independant assignments that need to be completed. -

Press Release Science Film Festival Ph

PRESS RELEASE SCIENCE FILM FESTIVAL PH reached 100,000 viewers! The Science Film Festival 2014 in the Philippines, organized by the Goethe- Institut in partnership with the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), the Department of Education (DepEd) and Mercedes-Benz, reached a total of 103,945 viewers – light-years of improvement from 2013’s reach of 26,500 – making the Philippines exactly in celebration of their 5th anniversary as host of the Science Film Festival the first country outside of the festival-initiator Thailand to break the 100,000 barrier. The Science Film Festival, promoting the theme “Future Technology”, took place in Goethe-Institut Philippinen the Philippines from November 4 to December 14 last year and kicked off with the G/4/5 F Adamson Centre opening film “Nine-and-a-half”: Life Without Plastics” (Germany). It was founded in 121 L. P. Leviste St., Salcedo Village Bangkok 10 years ago and aims to provide the younger generation access to 1227 Makati City, science to awaken their interest and encourage them to pursue a career in the Philippines T +63 2 840-5723 field of the sciences. International science films were shown in 14 countries from T +63 2 840-5724 Southeast Asia and the Middle East and the festival reached 580,079 viewers T +63 2 817-0978 F +63 2 817-0979 internationally. This number – a 30% leap from the 2013 figure – makes the www.goethe.de/philippinen Science Film Festival one of the biggest film festivals in the world in terms of [email protected] audience count. -

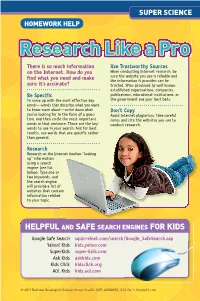

Research Like a Pro There Is So Much Information Use Trustworthy Sources on the Internet

SUPER SCIENCE HOMEWORK HELP Research Like a Pro There is so much information Use Trustworthy Sources on the Internet. How do you When conducting Internet research, be sure the website you use is reliable and find what you need and make the information it provides can be sure it’s accurate? trusted. Sites produced by well-known, established organizations, companies, Be Specific publications, educational institutions, or To come up with the most effective key- the government are your best bets. words—words that describe what you want to know more about—write down what Don’t Copy you’re looking for in the form of a ques- Avoid Internet plagiarism. Take careful tion, and then circle the most important notes and cite the websites you use to words in that sentence. Those are the key- conduct research. words to use in your search. And for best results, use words that are specific rather than general. Research Research on the Internet involves “looking up” information using a search engine (see list below). Type one or two keywords, and the search engine will provide a list of websites that contain information related to your topic. HELPFUL AND SAFE SEARCH ENGINES FOR KIDS Google Safe Search squirrelnet.com/search/Google_SafeSearch.asp Yahoo! Kids kids.yahoo.com SuperKids super-kids.com Ask Kids askkids.com Kids Click kidsclick.org AOL Kids kids.aol.com © 2015 National Geographic Society; Image Credits: (UP), AVAVA/SS; (LO), Chris Gorgio/IS.com 100-135 Science ALL EDITIONS_REL.indd 135 1/30/15 3:02 PM. -

Quino Checkerspot Butterfly Survey Report 2017

Western Riverside County Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan Biological Monitoring Program 2017 Quino Checkerspot Butterfly (Euphydryas editha quino) Survey Report 22 June 2018 2017 Quino Checkerspot Butterfly Survey Report TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND OBJECTIVES ................................................................................................................... 2 METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 3 PROTOCOL DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................................................ 3 STUDY SITE SELECTION ..................................................................................................................... 3 SURVEY METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 6 TRAINING ........................................................................................................................................... 7 DATA ANALYSIS ................................................................................................................................ 7 RESULTS .............................................................................................................................. 8 SENTINEL SITE SURVEYS .................................................................................................................. -

The Making of the National Geographic: Science, Culture, and Expansionism

jpn>w^sr"-ip ' & -a&^SSQ'wi The Making of the National Geographic: Science, Culture, and Expansionism Susan Schulten ... if Cuba and Puerto Rico, Alaska and Hawaii, and Luzon and her neighbors do not make America the fore most naval and shipping nation of the earth within a quarter-century, then experience stands for naught, history is a delusion, civilization a failure, and enlightenment a farce. W.J. McGee, Vice-President of the National Geographic Society, 18991 Five days before Christmas, in 1905, the National Geographic Society held an elaborate dinner in Washington, D.C. With over 200 guests—including explorers, diplomats, senators and congressmen—the Society was celebrating a membership that had grown from 3,400 to 11,000 in that year alone. The Society ' s President, Willis Moore, attributed this success to the character of its members, "the thinking, intellectual people of this city, of the nation, and somewhat from all nations—those who wish to keep abreast with the thought and activities of the world at large." For Moore, the public's interest in geography—as defined by the Society—fed the intellectual wealth of American civilization, which had since 1898 broken beyond its continental confines and "leaped forward from this island to that, [until] today we find the free institutions of this country planted at the very doors of the Orient." In turn, the nation's new role abroad intensified the need for the Society to translate the meaning of these changes, to illuminate "the world and all that is in it." The evening's guest of honor, Secretary of War William Howard 0026-3079/2000/4101-005$2.50/0 American Studies, 41:1 (Spring 2000): 5-29 5 6 Susan Schulten Taft, affirmed Moore's convictions by exalting the nation's great territorial and commercial gains, which sought "only to produce peace and prosperity the world around."2 By 1905 the survival of the National Geographic Society was assured. -

Access Top Physical, Mathematical and Engineering

Access top physical, mathematical and engineering research Your library subscribes to some of the Royal Society’s journals meaning you can access research from across the entire spectrum of physical, mathematical and Influential themed journal issues engineering sciences, including across the physical, mathematical archive content dating back to 1665. and engineering sciences Sign up for alerts at rsta.royalsocietypublishing.org royalsocietypublishing.org/alerts royalsociety.org/journals Publishing high-quality research High quality research across and review articles from all all of science, engineering and disciplines in the physical mathematics rspa.royalsocietypublishing.org rsos.royalsocietypublishing.org Cross-disciplinary research at Themed issues covering cross- the interface between the physical disciplinary research at the and life sciences interface between the physical and life sciences rsif.royalsocietypublishing.org rsfs.royalsocietypublishing.org The Royal Society For further information The Royal Society is a self-governing Fellowship The Royal Society of many of the world’s most distinguished scientists 6 – 9 Carlton House Terrace drawn from all areas of science, engineering, and London SW1Y 5AG medicine. The Society’s fundamental purpose, T +44 20 7451 2500 reflected in its founding Charters of the 1660s, is W royalsociety.org to recognise, promote, and support excellence in science and to encourage the development and use of science for the benefit of humanity. The Society’s strategic priorities are: • Promoting excellence in science • Supporting international collaboration • Demonstrating the importance of science to everyone Founded in 1660, the Royal Society is the independent scientific academy of the UK, dedicated to promoting excellence in science Registered Charity No 207043 Cover Image Issued: October 2017 DES5088 © MarquinhosLourenco.. -

Accelerate Learning Transforms Science Education Worldwide with Stemscopes Science Powered by CNN

Accelerate Learning Transforms Science Education Worldwide with Stemscopes Science Powered by CNN Next-generation digital curriculum combines hands-on investigations and exclusive CNN content to engage and inspire K-12 students to explore real-world science HOUSTON – Jan. 23, 2018 – Accelerate Learning, a global leader in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education, announced today a new platform using the best of CNN’s digital content to create a new science education product. This provides a new way to teach science and create the next generation of scientists, explorers, and problem solvers with the new Stemscopes™ Science powered by CNN digital curriculum. Stemscopes Science powered by CNN combines the award-winning Stemscopes K-12 digital science curriculum with content carefully curated from the best of CNN’s world-renowned news and current events archive. The next-generation science solution challenges students to innovate, create, and problem solve while connecting them to real-world events and issues that affect their lives. It includes a variety of assessments, from multiple-choice to claim-evidence-reasoning assessments, as well as extensive support for teachers such as embedded professional development and instructional resources to support a differentiated learning experience for each student. “For years, educators have struggled to provide students with engaging, inquiry-based instruction that not only builds a deep understanding in science but connects it to the real world,” said Dr. Vernon Johnson, -

A Management and Monitoring Plan for Quino Checkerspot Butterfly (Euphydryas Editha Quino) and Its Habitats in San Diego County

A Management and Monitoring Plan for Quino Checkerspot Butterfly (Euphydryas editha quino) and its Habitats in San Diego County Advisory Report to the County of San Diego Travis Longcore, Ph.D. The Urban Wildlands Group P.O. Box 24020 Los Angeles, CA 90024 Dennis D. Murphy, Ph.D. Department of Biology The University of Nevada, Reno Reno, NV 89557 Douglas H. Deutschman, Ph.D. Department of Biology San Diego State University San Diego, CA 92182 Richard Redak, Ph.D. Department of Entomology University of California, Riverside Riverside, CA 92521 Robert Fisher, Ph.D. USGS Western Ecological Research Center San Diego Field Station 5745 Kearny Villa Road, Suite M San Diego, CA 92123 December 30, 2003 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................... I LIST OF FIGURES...........................................................................................................................................................II LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................................................... III INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................................................................1 LIFE HISTORY OF THE BUTTERFLY AND AN ENVIROGRAM .......................................................................3 HABITAT MANAGEMENT ............................................................................................................................................8 -

Science Film Festival 2015 Promises to Be Bigger Than Ever

PRESS RELEASE Science Film Festival 2015 promises to be bigger than ever Mula Aparri hanggang Jolo -- almost. With more than 100 venues hosting screenings and science activities from October 19 to December 9, the Science Film Festival promises to keep true to its claim of being the largest festival of its kind this 2015. The Festival is a showcase of science films from all around the globe under the theme Light to coincide with the United Nations (UN) International Year of Light. It aims to promote science literacy and facilitates awareness of contemporary scientific, technological and environmental issues through the medium of film and television content. The roster of this year’s festival is composed of 44 science films from Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Philippines, among others. The films were reviewed and selected by a local selection committee made up of Goethe-Institut Philippinen representatives from the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), the UN G/4/5 F Adamson Centre International Year of Light Point of Contact, the Mind Museum, the Philippine Society 121 L. P. Leviste St., of Youth Science Clubs (PSYSC), the ABS-CBN Knowledge Channel, Museo Salcedo Village 1227 Makati City, Pambata and the University of the Philippines Astronomical Society. Philippines T +63 2 840-5723 An initiative of the Goethe-Institut, the Science Film Festival was first held in 2005 in T +63 2 840-5724 Thailand and has since grown considerably, meanwhile becoming the largest event T +63 2 817-0978 of its kind worldwide in terms of audience reach with 580 000 visitors in 13 countries F +63 2 817-0979 from Southeast Asia, the Middle East and North Africa in 2014.