Plan for Institutional Strengthening Ten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Divided Sarajevo: Space Management, Urban Landscape and Spatial Practices Across the Boundary Bassi, Elena

www.ssoar.info Divided Sarajevo: space management, urban landscape and spatial practices across the boundary Bassi, Elena Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Bassi, E. (2015). Divided Sarajevo: space management, urban landscape and spatial practices across the boundary. Europa Regional, 22.2014(3-4), 101-113. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-461616 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Attractive Sectors for Investment in Bosnia and Herzegovina

ATTRACTIVE SECTORS FOR INVESTMENT IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA TABLE OF CONTENTS TOURISM SECTOR IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA.........................................................................................7 TOURISM AND REAL ESTATE SECTOR PROJECTS IN BIH..................................................................................18 AGRICULTURE AND FOOD PROCESSING INDUSTRY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA............................20 AGRICULTURE SECTOR PROJECTS IN BIH......................................................................................................39 METAL SECTOR IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA...........................................................................................41 METAL SECTOR PROJECTS IN BIH.....................................................................................................................49 AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA............................................................................51 AUTOMOTIVE SECTOR PROJECTS IN BIH.........................................................................................................57 MILITARY INDUSTRY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA..................................................................................59 FORESTRY AND WOOD INDUSTRY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA.........................................................67 WOOD SECTOR PROJECTS IN BIH.....................................................................................................................71 ENERGY SECTOR IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA.........................................................................................73 -

Europe Report, Nr. 29: a Hollow Promise?

A HOLLOW PROMISE ? The Return of Bosnian Serb Displaced Persons to Drvar, Bosansko Grahovo and Glamoc ICG Bosnia Project - Report No 29 19 January 1998 ICG Bosnia Report - Hollow Promise? ….. Page: ii Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 II. Drvar, Bosansko Grahovo And Glamoc ......................................................... 3 III. Obstacles To Serb Returns To Canton 10 .................................................. 4 A. The HDZ in Drvar........................................................................................ 4 B. Violence in Martin Brod............................................................................... 5 C. Hostile Relocation of Croats into Serb homes ............................................ 6 D. Croat control of the local economy ............................................................. 7 E. The HVO in Drvar ....................................................................................... 8 F. The police ................................................................................................... 9 G. Glamoc Combat Training Centre................................................................ 9 H. Aid for Returnees: Hollow promise? ......................................................... 10 IV. The Coalition For Return............................................................................ -

Procurement Method Threshold

PROCUREMENT METHODS AND PRIOR REVIEW THRESHOLDS (a) Goods/Works: All ICB contracts for Goods and Works; Public Disclosure Authorized First two NCB contracts for Goods and First two NCB contracts for Works irrespective of the cost of the contract; First Shopping contract for Goods and First Shopping contract for Works. b) Consultants services FIRMS: All contracts with consulting firms estimated to cost US$300,000 or more; First contract with consulting firms selected on the basis of Consultants Qualifications (CQ) Individual Consultant Public Disclosure Authorized All contracts with individual consultants estimated to US$50,000 or more All contracts with PIU staff irrespective of the cost of the contract; General: - The Terms of Reference for all consultant contracts with consulting firms and individual consultants irrespective of their costs; Short lists comprising entirely national consultants shall be for assignments below USD 300,000; Public Disclosure Authorized Procurement method threshold ICB NCB $ USD $ USD Goods Works Goods Works ≥1.000.000 ≥ 5.000.000 < 1.000.000 <5.000.000 Prior review threshold ICB NCB Public Disclosure Authorized $ USD $ USD Goods Works Goods Works All All First 2& >2.000.000;First 2&>10.000.000 PROCUREMENT METHODS AND PRIOR REVIEW THRESHOLDS First two NCB contracts for Goods and First two NCB contracts for Works irrespective of the cost of the contract; First contract with consulting firms selected on the basis of Consultants Qualifications (CQ) - The Terms of Reference for all consultant contracts with consulting -

Profil Za Investitore

1 OPŠTINA SRBAC REPUBLIKA SRPSKA BOSNA I HERCEGOVINA PROFIL ZA INVESTITORE za investitore P r o f i l 2 1. Gdje se nalazi Srbac ? Opština Srbac nalazi se na sjeverozapadnom dijelu Republike Srpske i Bosne i Hercegovine i u neposrednoj je blizini (50 km, 45 minuta vožnje) od grada Banjaluka, jednog od najvećih urbanih centara u Bosni i Hercegovini sa oko 200 000 stanovnika. Graniči sa Republikom Hrvatskom, a udaljenost od graničnog prelaza u Gradišci je 35 km, dok je udaljenost od autoputa Beograd – Zagreb (glavne putne komunikacije u Hrvatskoj) 39 km. Srbac je komunikaciono dobro povezan i sa susjednim opštinama Laktašima, Prnjavorom, Derventom i Gradiškom. Zahvaljujući povoljnom strateškom položaju opština ima dobru putnu komunikaciju sa Hrvatskom, zemljama EU i zemljama Jugoistočne evrope. Ukupna površina teritorije opštine je 453 km2, a na teritoriji opštine živi oko 17 000 stanovnika, dok u njenom neposrednom okruženju živi oko 600 000 stanovnika. Ukoliko želite doći u Srbac koristeći avio Geografski položaj opštine Srbac saobraćaj, najbliži aerodrom sa redovnim međunarodnim letovima je aerodrom Pleso u Zagrebu (oko 180 km, moderni autoput) i aerodrom Butmir u Sarajevu (oko 250 km). U neposrednoj blizini je i aerodrom „Mahovljani“ u Banjaluci (oko 35 km), pogodan za charter letove. Opština Srbac je u privrednom smislu orijentisana na primarnu poljoprivrednu proizvodnju, zemljoradnju, te preradu i procesiranje poljoprivrednih proizvoda i proizvodnju hrane, živinarsku za investitore proizvodnju, ribogojstvo, svinjogojstvo, zatim drvopreradu, metalopreradu, proizvodnju plastičnih masa, ekstrakciju kaolina, riječnog šljunka, eksploataciju šumskih bogatstava. Obzirom na svoju geostratešku poziciju, blizinu granice sa Republikom Hrvatskom i EU, dobru povezanost sa ostatkom BiH, te blizinu velikog urbanog centra, Banjaluke, opština u zadnje vrijeme postaje sve interesantnija za P r o f i l 3 investitore koji pokreću različite proizvodne aktivnosti. -

Broj 25, Januar 2013. Godine

Bilten Broj 25, januar 2013. godine Predstavništvo rePublike srPske ustanova za unaPređenje ekonomske, naučno-tehničke, kulturne i sPortske saradnje između rePublike srPske i rePublike srbije IZDVAJAMO PREDSTAVNIŠTVO REPUBLIKE SRPSKE U SRBIJI SVEČANO OBILJEŽENI DAN I KRSNA SLAVA RS ARHEOLOŠKI KOMPLEKS SKELANI Bulevar despota Stefana 4/IV Beograd, Srbija KINOTEKA REPUBLIKE SRPSKE Tel: 00 381 11 324 6633 OPŠTINE RS: SRBAC Faks: 00 381 11 323 8633 E-mail: [email protected] Представништво реПублике срПске 2 Sadržaj U fokusu Dan i krsna slava Republike Srpske . 3 Majkrosoft u Srpskoj . 7 Kultura Čuvar našeg istorijskog pamćenja . 9 Nauka Arheološki kompleks Skelani . 12 Opštine RS Srbac . 15 Predstаvništvo rePublike srPske 3 U fokusu Dan i krsna slava Republike Srpske Republika Srpska pro- svete arhijerejske liturgije u budemo sijači ljubavi i mira, i slavila je Dan Republike i kr- Sabornom hramu Hrista Spa- da čuvamo jedinstvo naše dr- snu slavu Svetog arhiđakona sitelja u Banjaluci, kojoj su žave Republike Srpske“, poru- Stefana . U Sabornom hramu prisustvovali predsednik Srp- čio je vladika Vasilije . Hrista Spasitelja održana sve- ske Milorad Dodik, predstav- čana liturgija . Predsjednik RS nici izvršne i zakonodavne Dodjela ordenja Republike odlikovao zaslužne ličnosti i vlasti, kao i srpski predstavni- Srpske institucije . Održana svečana ci u institucijama BiH . akademija pod nazivom “Iz Vladika Vasilije je u obra- Predsjednik Republike Srpske s ljubavlju” na kojoj ćanju naglasio da je Republika Srpske Milorad Dodik je povo- se povodom jubileja obratio Srpska zalivena krvlju njenih dom Dana i krsne slave Srpske predsjednik Dodik . najboljih sinova i kćeri i poru- - Svetog arhiđakona Stefana, čio da Srpsku treba čuvati kao odlikovao Vojno-medicinsku Svečana liturgija zjenicu oka . -

Mapa Katastarskih Opština Republike Srpske

Mapa katastarskih opština Republike Srpske Donja Gradina Čuklinac Glavinac Kostajnica Petrinja Mlinarice Draksenić Babinac Bačvani Tavija Demirovac Suvaja KOSTAJNICA Jošik Vrioci Međeđa Mrakodol Gornja Johova Komlenac Orahova Slabinja Grdanovac Ševarlije Donja Slabinja Kozarska Kozarska Verija Dubica 1 Dubica 2 Mrazovci Bok Gumnjani Klekovci Jankovac Tuključani Gašnica Kalenderi Podoška Pobrđani Dobrljin Mraovo Dizdarlije Jasenje Parnice Novoselci Gunjevci Polje Hadžibajir Ličani Mačkovac Čelebinci Aginci Sključani Božići Donje Gradiška 1 Orubica Kuljani Sreflije Bistrica Kozinci Pobrđani Veliko KOZARSKA DUBICA Čitluk Dvorište Brekinje Bijakovac Greda Gornje Furde Ušivac Pucari Gornja Dolina Vodičevo Malo Bosanski Brod Vlaškovci Jelovac Čatrnja Brestovčina Donje Vodičevo Dvorište Gradiška 2 Kadin Novo Selo Bjelajci Donja Dolina Poloj Sovjak Gaj Strigova Međuvođe Gornje Jablanica Trebovljani Murati Mirkovci Vlaknica Ravnice Odžinci Sreflije Liskovac Dumbrava Miloševo Brdo Žeravica Laminci Jaružani Cerovica Vrbaška Bardača Močila Križanova Laminci Sijekovac Donja Gornja Rakovica Bukovac Laminci Brezici Srednji Srbac Selo Gradina Močila Gornja Prusci Hajderovci Brusnik Čikule Kolibe Donje Velika Lješljani Donji Jelovac Bajinci Gornjoselci Mala Žuljevica Kriva Rijeka Sjeverovci Srbac Mjesto Kaoci Žuljevica Maglajci Koturovi Lužani Grabašnica Jutrogošta Laminci Dubrave Dugo Polje Vojskova Dubrave Liješće Mlječanica Devetaci Bukvik Rasavac Poljavnice Donji Podgradci Kobaš Mazići Rakovac Košuća Kolibe Gornje Nova Ves Novo Selo Zbjeg Dragelji -

Bosnia and Herzegovina Investment Opportunities

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA KEY FACTS..........................................................................6 GENERAL ECONOMIC INDICATORS....................................................................................7 REAL GDP GROWTH RATE....................................................................................................8 FOREIGN CURRENCY RESERVES.........................................................................................9 ANNUAL INFLATION RATE.................................................................................................10 VOLUME INDEX OF INDUSTRIAL PRODUCTION IN B&H...............................................11 ANNUAL UNEMPLOYMENT RATE.....................................................................................12 EXTERNAL TRADE..............................................................................................................13 MAJOR FOREIGN TRADE PARTNERS...............................................................................14 FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT IN B&H.........................................................................15 TOP INVESTOR COUNTRIES IN B&H..............................................................................17 WHY INVEST IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA..............................................................18 TAXATION IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA..................................................................19 AGREEMENTS ON AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION...............................................25 -

National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe Volume 36 Issue 5 Article 3 10-2016 National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina Ivan Cvitković University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree Part of the Christianity Commons, and the Eastern European Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cvitković, Ivan (2016) "National and Confessional Image of Bosnia and Herzegovina," Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe: Vol. 36 : Iss. 5 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ree/vol36/iss5/3 This Article, Exploration, or Report is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONAL AND CONFESSIONAL IMAGE OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA1 Ivan Cvitković Ivan Cvitković is a professor of the sociology of religion at the University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. He obtained the Master of sociological sciences degree at the University in Zagreb and the PhD at the University in Ljubljana. His field is sociology of religion, sociology of cognition and morals and religions of contemporary world. He has published 33 books, among which are Confession in war (2005); Sociological views on nationality and religion (2005 and 2012); Social teachings in religions (2007); and Encountering Others (2013). e-mail: [email protected] The population census offers great data for discussions on the population, language, national, religious, social, and educational “map of people.” Due to multiple national and confessional identities in Bosnia and Herzegovina, such data have always attracted the interest of sociologists, political scientists, demographers, as well as leaders of political parties. -

Elektrokrajina Power Distribution Project - Non-Technical Summary

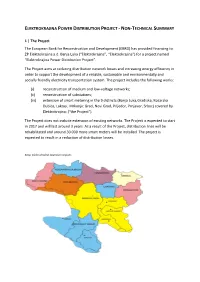

ELEKTROKRAJINA POWER DISTRIBUTION PROJECT - NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY 1 | The Project The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) has provided financing to ZP Elektrokrajina a.d. Banja Luka (“Elektrokrajina”, “Elektrokrajina”) for a project named “Elektrokrajina Power Distribution Project”. The Project aims at reducing distribution network losses and increasing energy efficiency in order to support the development of a reliable, sustainable and environmentally and socially friendly electricity transportation system. The project includes the following works: (i) reconstruction of medium and low-voltage networks; (ii) reconstruction of substations; (iii) extension of smart metering in the 9 districts (Banja Luka,Gradiska, Kozarska Dubica, Laktasi, Mrkonjic Grad, Novi Grad, Prijedor, Prnjavor, Srbac) covered by Elektrokrajina; (“the Project”). The Project does not include extension of existing networks. The Project is expected to start in 2017 and will last around 3 years. As a result of the Project, distribution lines will be rehabilitated and around 30 000 more smart meters will be installed. The project is expected to result in a reduction of distribution losses. Map: Elektrokrajina operation regions 2 | Elektrokrajina Elektrokrajina was initially established as one of the regional electricity distribution companies in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1995 Elektrokrajina became a subsidiary of EPRS and in October 2005 was transformed into a stock-company listed on the Banja Luka Stock Exchange. Currently, Elektrokrajina is majority (65 per cent) owned by EPRS. Elektrokrajina is responsible for power distribution and is a power supplier in the Banja Luka region of the Republika Srpska. Elektrokrajina owns and operates the power distribution networks of up to 110 kV. Elektrokrajina operates 21500 km of network, 4100 substations/transformers and serves 260 000 customers, out of which only 10% were before the Project equipped with a smart meter. -

Democracy Assessment in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Democracy Assessment in Bosnia and Herzegovina Sarajevo, 2006. Democracy Assessment in Bosnia and Herzegovina Contributing Authors: Sr|an Dizdarevi}, Sevima Sali-Terzi}, Mr. Ramiz Huremagi}, Dr. Nedim Ademovi} Mr. Kenan Ademovi}, Rebeka Kotlo, Mr. Esref Kenan Ra{idagi}, Antonio Prlenda, Mr. Boris Divjak Dr. Tarik Jusi}, Mr. Reima Ana Maglajli}, Edin Hod`i}, Mr. Zdravko Miov~i} Dr. @arko Papi}, Dr. Lada Sadikovi}, Project Coordinators: Mervan Mira{~ija, Open Society Fund Bosnia and Herzegovina Selma Zahirovi}, Open Society Fund Bosnia and Herzegovina Published by: Open Society Fund Bosnia and Herzegovina, Sarajevo, Mar{ala Tita 19 Translated by: Amira Sadikovi}, Spomenka Beus Edited by: Sr|an Dizdarevi}, Dobrila Govedarica, Tarik Jusi}, Mervan Mira{~ija, Svjetlana Nedimovi}, E{ref Kenan Ra{idagi}, Selma Zahirovi} Proof-read and copy-edited by: Christopher Biehl Cover design by: Miodrag Spasojevi} [trika - «Y Studio» doo Sarajevo Layout, design and DTP by: Müller d.o.o. Printed by: Müller d.o.o. Sarajevo Circulation: 200 copies Edition: February 2006. CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo 342:321.7] (497.6) (082) Democracy Assessment in Bosnia and Herzegovina ; / [contributing authors Sr|an Dizdarevi} ... [et. al.] ; translated by Amira Sadikovi}, Spomenka Beus] . - Sarajevo : Open Society Fund Bosnia & Herzegovina, 2006. - 471 str. : graf. prikazi ; 30 cm Prijevod djela: Procjena razvoja demokratije u Bosni i Hercegovini. - Bibliografija i bilje{ke uz tekst ISBN 9958-749-02-5 -

Pregled Poslodavaca Kojima Su Odobrena Sredstava Po "Program Podrške Zapošljavanju Mladih Sa Vss U Statusu Pripravnika U 2020

PREGLED POSLODAVACA KOJIMA SU ODOBRENA SREDSTAVA PO "PROGRAM PODRŠKE ZAPOŠLJAVANJU MLADIH SA VSS U STATUSU PRIPRAVNIKA U 2020. GODINI" KOMPONENTA III - LICA BEZ RADNOG ISKUSTVA SA VSS NA SJEDNICI UPRAVNOG ODBORA OD 04.09.2020.GODINE Rb. Biro Filijala NAZIV POSLODAVCA LICA 1 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka UDRUŽENjE GRAĐANA "POZITIVNE SNAGE SRPSKE" BANjA LUKA 2 2 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka JU O.Š. ,,Sveti Sava" Banja Luka 2 3 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka JU Centar "ZAŠTITI ME" Banja Luka 1 4 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka JZU Institut za javno zdravstvo Republike Srpske 19 5 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka UDRUŽENJE ZA CEREBRALNU PARALIZU - CPOSSIBLE 1 6 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka "AUTOMATIKON" Srećko Gajić s.p. Banja Luka 1 7 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka J.P. RTRS Banja Luka 2 8 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka "Grafo-komerc" d.o.o. Banja Luka 1 9 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka Grad Banja Luka 1 10 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka ADVOKAT MILAN D. PETKOVIĆ BANjA LUKA 2 11 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka Vijeće naroda RS 2 12 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka "OSIGURANJE AURA" a.d. Banja Luka 1 13 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka Zavod "Dr ZOTOVIĆ" Banja Luka 1 14 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka JU Osnovna škola "Branko Radičević" Banja Luka 3 15 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka "VETMEDIK" Draško Polić s.p. Banja Luka 1 16 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka "EUPHORIA" d.o.o. 1 17 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka "POŠTE SRPSKE" A.D. Banja Luka 20 18 Biro Banja Luka Banja Luka "BAUSTATIK" d.o.o.