Analyzing the Impact of Redevelopment on Urban Communities: Developing Strategies for Successful Inclusive Integration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Déjà Vu Gentrification: Prospects for Community Mobilization in New York City’S Lower East Side and Chinatown in the Post-9/11 Era

Déjà Vu Gentrification: Prospects for Community Mobilization in New York City’s Lower East Side and Chinatown in the Post-9/11 Era by Deland Chan B.A. (Stanford University) 2007 M.A. (Stanford University) 2007 A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of City Planning in City and Regional Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ananya Roy, Chair Professor Teresa Caldeira Professor Michael Omi Spring 2009 The thesis of Deland Chan is approved: Chair ______________________________________________ Date _____________ ______________________________________________ Date _____________ ______________________________________________ Date _____________ University of California, Berkeley i Acknowledgements The act of writing a thesis is often envisioned as a one-person endeavor consisting of typing furiously on the keyboard—often late at night—while little is known that it takes an army of professors, family, and friends and their constant support to make it happen. I would like to thank Teresa Caldeira and the Master’s thesis writing group— Hun Kim, Sergio Montero, and Oscar Sosa—for your help throughout the writing process. I appreciate your insightful comments and steady collegial support. Our meetings have transformed my thesis into a rewarding project. Ananya Roy has offered encouragement at every step in the journey, whether guiding me through the realities of fieldwork or ensuring the logical cohesion of my thesis. Michael Omi has offered invaluable mentorship throughout this process, and I appreciate his contribution in shaping the numerous drafts. Lastly, I would like to thank Genni Low for her transcription assistance, Michael Huang for ensuring that I eat at least three meals a day in my quest to stay hungry and foolish, and perhaps most importantly, the residents of the Lower East Side and Chinatown for sharing their insights with me. -

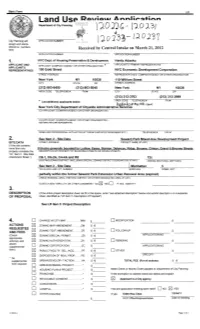

NOTICE of CERTIFICATION Pursuant to the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure

NOTICE OF CERTIFICATION Pursuant to the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure Application #: C 130321 ZSM Project Name: 180 Orchard Street Public Parking Garage CEQR Number: 12DCP191M Borough(s): Manhattan Community District Number(s): 3 Please use the above application number on all correspondence concerning this application Docket Description: IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by 180 Orchard Retail LLC pursuant to Sections 197-c and 201 of the New York City Charter for the grant of a special permit pursuant to Zoning Resolution Section 13-45 (Special Permits for additional parking spaces) and Section 13-451 (Additional parking spaces for residential growth) to allow an attended public parking garage with a maximum capacity of 99 spaces on portions of the ground floor, cellar and sub-cellar of a proposed mixed-use building on property located at 180 Orchard Street (Block 412, Lots 8-11, 27-29, 32-36, & 1001-1003), in a C4-4A District, Borough of Manhattan, Community District 3. Plans for this proposal are on file with the City Planning Commission and may be seen in Room 3N, 22 Reade Street, New York, N.Y. 10007. Related Applications: Applicant(s): Applicant’s Representative: 180 Orchard Retail LLC Paul D. Selver c/o Cohen Equities Kramer Levin Naftalis & Frankel LLP 675 Third Avenue, Suite 2400 1177 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10017 New York, NY 10036 Contact: Address questions about this application to the following DCP office: DEPARTMENT OF CITY PLANNING Manhattan Office Address: 22 Reade Street, 6th Fl. West, New York, NY 10007-1216 Phone: 212-720-3480 Fax: 212-720-3488 Public Review Timeline: On October 20, 2014 the above listed application was certified as complete by the Department of City Planning. -

Zoning Text Amendment (ZR Sections 74-743 and 74-744) 3

UDAAP PROJECT SUMMARY Site BLOCK LOT ADDRESS Site 1 409 56 236 Broome Street Site 2 352 1 80 Essex Street Site 2 352 28 85 Norfolk Street Site 3 346 40 (p/o) 135-147 Delancey Street Site 4 346 40 (p/o) 153-163 Delancey Street Site 5 346 40 (p/o) 394-406 Grand Street Site 6 347 71 178 Broome Street Site 8 354 1 140 Essex Street Site 9 353 44 116 Delancey Street Site 10 354 12 121 Stanton Street 1. Land Use: Publicly-accessible open space, roads, and community facilities. Residential uses - Sites 1 – 10: up to 1,069,867 zoning floor area (zfa) - 900 units; LSGD (Sites 1 – 6) - 800 units. 50% market rate units. 50% affordable units: 10% middle income (approximately 131-165% AMI), 10% moderate income (approximately 60-130% AMI), 20% low income, 10% senior housing. Sufficient residential square footage will be set aside and reserved for residential use in order to develop 900 units. Commercial development: up to 755,468 zfa. If a fee ownership or leasehold interest in a portion of Site 2 (Block 352, Lots 1 and 28) is reacquired by the City for the purpose of the Essex Street Market, the use of said interest pursuant to a second disposition of that portion of Site 2 will be restricted solely to market uses and ancillary uses such as eating establishments. The disposition of Site 9 (Block 353, Lot 44) will be subject to the express covenant and condition that, until a new facility for the Essex Street Market has been developed and is available for use as a market, Site 9 will continue to be restricted to market uses. -

Rock Clubs and Gentrification in New York City: the Case of the Bowery Presents

Rock Clubs and Gentrification in New York City: The Case of The Bowery Presents Fabian Holt University of Roskilde [email protected] Abstract This article offers a new analytical perspective on the relation between rock clubs and gentrification to illuminate broader changes in urbanism and cultural production in New York City. Although gentrification is central to understanding how the urban condition has changed since the 1960s, the long-term implications for popular music and its evolution within new urban populations and cultural industries have received relatively little scholarly attention. Gentrification has often been dismissed as an outside threat to music scenes. This article, in contrast, argues that gentrification needs to be understood as a broader social, economic, and cultural process in which popular music cultures have changed. The argument is developed through a case study of The Bowery Presents, a now dominant concert promoter and venue operator with offices on the Lower East Side. Based on fieldwork conducted over a three-year period and on urban sociological macro-level analysis, this article develops an analytical narrative to account for the evolution of the contemporary concert culture in the mid-size venues of The Bowery Presents on the Lower East Side and Williamsburg, Brooklyn, as a particular instance of more general dynamics of culture and commerce in contemporary cities. The narrative opens up new perspectives for theorizing live music and popular culture within processes of urban social change. The article begins by reviewing conventional approaches to rock music clubs in popular music studies and urban sociology. These approaches are further clarified through the mapping of a deep structure in how music scenes have framed the relationship between clubs and gentrification discursively. -

FOB 07-09.Indd

July 2009 Serving the communities along the Biscayne Corridor, including Arch Creek East, Bay Point, Bayside, Biscayne Park, Belle Meade, Buena Vista, Design District, Downtown, Edgewater, El Portal, Hibiscus Island, Keystone Point, Miami Shores, Morningside, North Bay Island, North Miami, Oakland Grove, Palm Grove, Palm Island, Sans Souci, Shorecrest, Star Island, Wynwood, and Venetian Islands www.BiscayneTimes.com Volume 7, Issue 5 Dirt & Dreams By Christian Cipriani Cover photo by Silvia Ros Illustration by James Dougherty All those vacant lots in Edgewater? We have plans for them! ew areas along the Biscayne Cor- small waterfront enclave was at the heart Real estate developers, a number of demolished what was already a rare com- ridor blossomed so brightly, then of Miami’s “Manhattanization” — a whom had no experience building high- modity in Miami: affordable housing. Fsuffered so deeply from the recent projected home to more than 6000 new rise condominiums (or much of anything In one sense, the frenzy of activity building boom and bust as Edgewater. luxury lofts and condos, and a hip, fresh else), swarmed over the low-rise neigh- was understandable. Geographically But Edgewater isn’t like most neighbor- destination for young professionals and borhood, gobbled up apartment buildings, hoods. Less than fi ve years ago, this Miami Beach exiles. evicted tenants by the hundreds, and Continued on page 14 CALL 305-756-6200 FOR INFORMATION ABOUT THIS ADVERTISING SPACE Our Collection of Unique Properties... Bring the family, A+school system, guard gated, 5/4.5, 3600sf, pool, dock, no bridges. GREAT DEAL! NewKeystone to market...Bay Point waterfront Harbor Townhouse on quiet 2+den/2.5,cul-de-sac, Bring all offers! $995K 2 car gar, pool $469K4/3, pool, or for A+schools. -

CHANGING TIDES in RED HOOK As Residential Developers Clamor to Build on the Brooklyn Waterfront, Industrialists Such As John Quadrozzi Jr

CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS NEW YORK BUSINESS® JANUARY 22 - 28, 2018 | PRICE $3.00 CHANGING TIDES IN RED HOOK As residential developers clamor to build on the Brooklyn waterfront, industrialists such as John Quadrozzi Jr. ght to keep their businesses a oat PAGE 13 PLUS: Pressure mounts on Port Authority to cash in on the Red Hook Container Terminal PAGE 16 VOL. XXXIV, NO. 4 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM CONGESTION WILL ESSEX THE LIST PRICING GETS CROSSING Largest A REBOOT UNITE THE executive- P. 3 AND P. 5 LOWER recruiting EAST SIDE? rms P. 10 NEWSPAPER P. 8 P001_CN_20180122.indd 1 1/19/18 8:15 PM JANUARY 22 - 28, 2018 CRAINSNEW YORK BUSINESS FROM THE NEWSROOM | ERIK ENGQUIST | ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR IN THIS ISSUE A how-not-to for op-eds 4 IN CASE YOU MISSED IT Sony/ATV artists have 5 POLITICS more than SOME YEARS AGO Crain’s began accepting op-ed submis- 100 nomi- 6 ASKED & ANSWERED nations for sions and publishing two to four each month. Now we this week’s 7 TECHNOLOGY receive that many every day, run as many as we can online Grammy and perhaps one in each print issue. I screen all of them and 8 WHO OWNS THE BLOCK Awards edit the ones we use. is helps me understand all the issues 9 VIEWPOINTS our readers care about, but it takes a tremendous amount of 10 THE LIST time. I’m going to try to cut down on some of that time right FEATURES: THE FUTURE OF RED HOOK now by sharing with all of you—businesspeople, advocates, PR professionals, public ocials and ordinary readers— 13 WORKING THE WATERFRONT the keys to getting your pieces rejected. -

Prime Manhattan Development Prime Manhattan Development Company Bio

PRIME MANHATTAN DEVELOPMENT PRIME MANHATTAN DEVELOPMENT COMPANY BIO Prime Manhattan Development focuses on mixed-use luxury residential investments and developments in Prime Manhattan in a manner that helps create and enhance the built environment through a focus on innovative design and superior construction. Prime Manhattan has owned, developed and managed real estate across various asset classes. GRANT SHAPOLSKY Founder & Managing Principal Mr. Shapolsky is a third–generation investor / developer. Mr. Shapolsky has been developing Manhattan property for 24 years and his family has been developing for 86. Mr. Shapolsky has spearheaded the acquisition and development of over two million square feet in Prime Manhattan consisting of mostly downtown loft property with a focus on IMD buildings, class B & C office parcels, and the purchase of defaulted loans / spoiled partnership interests. GRANT SHAPOLSKY DEVELOPMENT HISTORY Mr. Shapolsky has developed, managed and sold New York properties consisting mostly of Manhattan Proper. The history of his family is featured in a permanent traveling exhibit in the Whitney Museum. SHAPOLSKY FAMILY HOLDINGS IN THE WHITNEY MUSEUM A PERMANENT TRAVELING EXHIBIT Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971 - Hans Haake This Exhibit documents the ownership and control of urban space. The work exposes the properties and transactions of Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, which in 1971 represented the biggest concentration of real estate in New York under one group, and it is still an active corporation today. The properties of the group were found primarily in the Lower East Side and Harlem, two neighbourhoods characterised by their ethnic and racial minorities. -

C 120228 Zsm Corrected

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION August 22, 2012 / Calendar No. 9 C 120228 ZSM CORRECTED IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by the NYC Department of Housing Preservation & Development pursuant to Sections 197-c and 201 of the New York City Charter, for the grant of special permits pursuant to the following sections of the Zoning Resolution: 1. 74-743(a)(1) to modify the applicable district regulations to allow the distribution of total allowable floor area, dwelling units and lot coverage under the applicable district regulations within a large-scale general development without regard for zoning lot lines or district boundaries; 2. 74-743(a)(2) to modify the applicable district regulations to allow the location of buildings without regard for the applicable yard, court, distance between buildings, height and setback regulations; and 3. 74-743(a)(10) to modify the applicable district regulations to allow the areas of the zoning lot between the street line and the street walls of the proposed buildings to be improved as publicly-accessible widened sidewalk; in connection with a proposed mixed use development, within a large-scale general development bounded by Delancey Street, a line 150 feet easterly of Clinton Street, Broome Street, Clinton Street, Grand Street, Suffolk Street, Broome Street, Essex Street, a line 95.62 feet northerly of Broome Street, a line 50.54 feet westerly of Essex Street, Broome Street, Ludlow Street, a line 155 feet northerly of Broome Street, and Essex Street (Block 346, p/o Lot 40, Block 347, Lot 71, Block 352, Lots 1 & 28, and Block 409, Lot 56), in R8/C2-5 and C6-1 Districts, partially within the former Seward Park Extension Urban Renewal Area, Manhattan, Community District 3. -

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION August 22, 2012 / Calendar No. 9 C

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION August 22, 2012 / Calendar No. 9 C 120228 ZSM IN THE MATTER OF an application submitted by the NYC Department of Housing Preservation & Development pursuant to Sections 197-c and 201 of the New York City Charter, for the grant of special permits pursuant to the following sections of the Zoning Resolution: 1. 74-743(a)(1) to modify the applicable district regulations to allow the distribution of total allowable floor area, dwelling units and lot coverage under the applicable district regulations within a large-scale general development without regard for zoning lot lines or district boundaries; 2. 74-743(a)(2) to modify the applicable district regulations to allow the location of buildings without regard for the applicable yard, court, distance between buildings, height and setback regulations; and 3. 74-743(a)(10) to modify the applicable district regulations to allow the areas of the zoning lot between the street line and the street walls of the proposed buildings to be improved as publicly-accessible widened sidewalk; in connection with a proposed mixed use development, within a large-scale general development bounded by Delancey Street, a line 150 feet easterly of Clinton Street, Broome Street, Clinton Street, Grand Street, Suffolk Street, Broome Street, Essex Street, a line 95.62 feet northerly of Broome Street, a line 50.54 feet westerly of Essex Street, Broome Street, Ludlow Street, a line 155 feet northerly of Broome Street, and Essex Street (Block 346, p/o Lot 40, Block 347, Lot 71, Block 352, Lots 1 & 28, and Block 409, Lot 56), in R8/C2-5 and C6-1 Districts, partially within the former Seward Park Extension Urban Renewal Area, Manhattan, Community District 3. -

Rock Clubs and Gentrification in New York City: the Case of the Bowery Presents

Rock Clubs and Gentrification in New York City: The Case of The Bowery Presents Fabian Holt University of Roskilde [email protected] Abstract This article offers a new analytical perspective on the relation between rock clubs and gentrification to illuminate broader changes in urbanism and cultural production in New York City. Although gentrification is central to understanding how the urban condition has changed since the 1960s, the long-term implications for popular music and its evolution within new urban populations and cultural industries have received relatively little scholarly attention. Gentrification has often been dismissed as an outside threat to music scenes. This article, in contrast, argues that gentrification needs to be understood as a broader social, economic, and cultural process in which popular music cultures have changed. The argument is developed through a case study of The Bowery Presents, a now dominant concert promoter and venue operator with offices on the Lower East Side. Based on fieldwork conducted over a three-year period and on urban sociological macro-level analysis, this article develops an analytical narrative to account for the evolution of the contemporary concert culture in the mid-size venues of The Bowery Presents on the Lower East Side and Williamsburg, Brooklyn, as a particular instance of more general dynamics of culture and commerce in contemporary cities. The narrative opens up new perspectives for theorizing live music and popular culture within processes of urban social change. The article begins by reviewing conventional approaches to rock music clubs in popular music studies and urban sociology. These approaches are further clarified through the mapping of a deep structure in how music scenes have framed the relationship between clubs and gentrification discursively. -

Historic and Cultural Resources A. INTRODUCTION

Chapter 7: Historic and Cultural Resources A. INTRODUCTION This chapter considers the potential of the proposed actions to affect historic and cultural resources, both archaeological and architectural. It has been prepared in accordance with City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) guidelines, the State Environmental Quality Review Act, and Section 14.09 of the New York State Historic Preservation Act of 1980. These laws and regulations require that City and state agencies, respectively, consider the impacts of their actions on historic and cultural resources. In addition, because construction financing may come from New York State and/or the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), this chapter has also been prepared in accordance with the New York State Historic Preservation Act of 1980 (Section 14.09 of the New York Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation Law) and Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. In accordance with CEQR guidelines, this analysis identifies all historic and cultural resources that have been designated or determined to meet the eligibility requirements for local, state, or national designation, and it also identifies properties that may meet such eligibility requirements. In assessing potential project effects on historic and cultural resources, this analysis follows the guidance of the CEQR Technical Manual (January 2012 edition). The CEQR Technical Manual recommends that a historic resources assessment be performed if a proposed action would result in any of the following actions: in-ground disturbance; new construction, demolition, or significant physical alteration of any building, structure, or object; the change in scale, visual prominence, or visual context of any building, structure, or object or landscape feature; or the screening or elimination of publicly accessible views, even if no known historic resources are located nearby. -

12DCP191M: 180 Orchard Street

180 Orchard Street Public Parking Garage Environmental Assessment Statement CEQR #: 12DCP191M ULURP #: 130321ZSM Prepared For: NYC Department of City Planning Prepared on Behalf of: 180 Orchard Retail, LLC Prepared by: Philip Habib & Associates October 16, 2014 180 Orchard Street Public Parking Garage Environmental Assessment Statement CEQR No.: 12DCP191M Table of Contents EAS Form Attachment A…………………………………………………Project Description Attachment B………………………………………….Supplemental Screening Appendices Supplemental Screening Appendix A National Register of Historic Places Registration Form Supplemental Screening Appendix B New York City Landmarks Preservation Committee Letter EAS FULL FORM PAGE 1 City Environmental Quality Review ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT STATEMENT (EAS) FULL FORM Please fill out and submit to the appropriate agency (see instructions) Part I: GENERAL INFORMATION PROJECT NAME 180 Orchard Street Public Parking Garage 1. Reference Numbers CEQR REFERENCE NUMBER (to be assigned by lead agency) BSA REFERENCE NUMBER (if applicable) 12DCP191M ULURP REFERENCE NUMBER (if applicable) OTHER REFERENCE NUMBER(S) (if applicable) 130321ZSM (e.g., legislative intro, CAPA) 2a. Lead Agency Information 2b. Applicant Information NAME OF LEAD AGENCY NAME OF APPLICANT New York City Department of City Planning 180 Orchard Retail LLC NAME OF LEAD AGENCY CONTACT PERSON NAME OF APPLICANT’S REPRESENTATIVE OR CONTACT PERSON Robert Dobruskin, AICP, Director, EARD c/o Cohen Equities ADDRESS 22 Reade Street, 4E ADDRESS 675 Third Avenue, Suite 2400 CITY New York STATE NY ZIP 10007 CITY New York STATE NY ZIP 10017 TELEPHONE 212-720-3423 EMAIL TELEPHONE 212-279-9000 EMAIL [email protected] 3. Action Classification and Type SEQRA Classification UNLISTED TYPE I: Specify Category (see 6 NYCRR 617.4 and NYC Executive Order 91 of 1977, as amended): 6NYCRR Part 617.4(b)(9): Any Unlisted Action occuring wholly or partially within, or substantially contiguous to any historic building, structure, site or district.