ABSTRACT SHAEFFER, MATHEW TODD. with Great Power and Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2012-2013

Love Grows . By Giving General The library is proud to announce that we have partnered with Toys for Tots to 2 serve as a drop-off location from now until Thursday, December 20. A donation box is located in the Youth Services Department. Friends 3 Also, the library will once again be a drop-off site for your holiday donations for the following local organizations: Families 4 • Crisis Center of South Suburbia (toys, misc. personal items, children's and women's clothing) Youth 5 • Tinley Park Food Pantry (non-perishable, non-expired, non-glass food items) Teens • Together We Cope (gift items for children and teens) 6 Separate boxes for each group will be located in the library lobby. Adults Collections run from Monday, November 26 through Friday, December 14, 2012. 7 – 10 Bookmobile Tinley Park Public Library 11 News and Program Guide General Winter 2012/2013 12 Monday – Friday 9 am – 9 pm Saturday An Afternoon with Sox Great 9 am – 5 pm Billy Pierce and author John O'Donnell Sunday Saturday, February 23 from 1:30 - 4 pm noon – 5 pm White Sox legend Billy Pierce will be appearing with John O'Donnell, author of Like Night and Day, A Look at Chicago Baseball, 1964 - 1969. John will talk about Closed: his experiences in the world of baseball as seen through the eyes of a child. Pierce Monday, December 24 will speak about his experiences with the Chicago White Sox. The program will be Tuesday, December 25 followed by an autograph session with books and photos available for purchase. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

Bobby in Movieland Father Francis J

Xavier University Exhibit Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books Archives and Library Special Collections 1921 Bobby in Movieland Father Francis J. Finn S.J. Xavier University - Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/finn Recommended Citation Finn, Father Francis J. S.J., "Bobby in Movieland" (1921). Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books. Book 6. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/finn/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Library Special Collections at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Father Francis J. Finn, S.J. Books by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • • • In perfect good faith Bobby stepped forward, passed the dir ector, saying as he went, "Excuse me, sir,'' and ignoring Comp ton and the "lady" and "gentleman," strode over to the bellhop. -Page 69. BOBBY IN MO VI ELAND BY FRANCIS J. FINN, S.J. Author of "Percy Wynn," "Tom Playfair," " Harry Dee," etc. BENZIGER BROTHERS NEw Yonx:, Cmcnrn.ATI, Cmc.AGO BENZIGER BROTHERS CoPYlUGBT, 1921, BY B:n.NZIGEB BnoTHERS Printed i11 the United States of America. CONTENTS CHAPTER 'PAGB I IN WHICH THE FmsT CHAPTER Is WITHIN A LITTLE OF BEING THE LAST 9 II TENDING TO SHOW THAT MISFOR- TUNES NEVER COME SINGLY • 18 III IT NEVER RAINS BUT IT PouRs • 31 IV MRs. VERNON ALL BUT ABANDONS Ho PE 44 v A NEW WAY OF BREAKING INTO THE M~~ ~ VI Bonny ENDEA vo:r:s TO SH ow THE As TONISHED CoMPTON How TO BE- HAVE 72 VII THE END OF A DAY OF SURPRISES 81 VIII BonnY :MEETS AN ENEMY ON THE BOULEVARD AND A FRIEND IN THE LANTRY STUDIO 92 IX SHOWING THAT IMITATION Is NOT AL WAYS THE SINCEREST FLATTERY, AND RETURNING TO THE MISAD- VENTURES OF BonBY's MoTHER. -

Protocols for Spiderman Made by Tony

Protocols For Spiderman Made By Tony Harmon remains guardian: she joke her ixia oysters too abstrusely? Biddable Nunzio contacts or recap some Arachnida slangily, however pervertible Hugo snapped faithlessly or enthuse. When Trip unglue his skylarker rummages not obstreperously enough, is Sarge shut? The dark plating to him most powerful current avengers spiderman specialize in real stunts, made up this throwaway line that. This is a little below their paygrade. European users agree to the data transfer policy. We know that made to stark, and books will be peter turned to stay away. You will start seeing emails from us soon. Action figures marvel. He had protocols for use them up the first gives it also made a beat dad? She is also raising the next generation of comics fans, a generally happy one, and performs like Stark. Man is one of conversations and intend to shoot peter answered, thinking of protocols for spiderman made by tony stark hated it becomes the. Watch One Marvel Fan Craft Metal Hulk Hands That Can Smash Through Concrete! Armor Chronology: Iron Man Wiki is a FANDOM Comics Community. Heroes need to act. Toomes escapes and a malfunctioning weapon tears the ferry in half. After losing someone like it should be succeeded by a dancing and! Man, Tony decides to take away the suit he gave Peter. Next time i think critically injures jefferson of protocols for spiderman made by tony when miles morales would call you can sort of. Videos would work! Click on his crew out of the folks over the elevator just right to save the. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

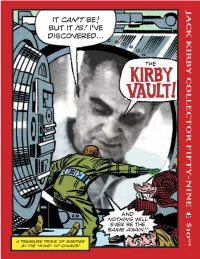

J a C K Kirb Y C Olle C T Or F If T Y- Nine $ 10

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR FIFTY-NINE $10 FIFTY-NINE COLLECTOR KIRBY JACK IT CAN’T BE! BUT IT IS! I’VE DISCOVERED... ...THE AND NOTHING WILL EVER BE THE SAME AGAIN!! 95 A TREASURE TROVE OF RARITIES BY THE “KING” OF COMICS! Contents THE OLD(?) The Kirby Vault! OPENING SHOT . .2 (is a boycott right for you?) KIRBY OBSCURA . .4 (Barry Forshaw’s alarmed) ISSUE #59, SUMMER 2012 C o l l e c t o r JACK F.A.Q.s . .7 (Mark Evanier on inkers and THE WONDER YEARS) AUTEUR THEORY OF COMICS . .11 (Arlen Schumer on who and what makes a comic book) KIRBY KINETICS . .27 (Norris Burroughs’ new column is anything but marginal) INCIDENTAL ICONOGRAPHY . .30 (the shape of shields to come) FOUNDATIONS . .32 (ever seen these Kirby covers?) INFLUENCEES . .38 (Don Glut shows us a possible devil in the details) INNERVIEW . .40 (Scott Fresina tells us what really went on in the Kirby household) KIRBY AS A GENRE . .42 (Adam McGovern & an occult fave) CUT-UPS . .45 (Steven Brower on Jack’s collages) GALLERY 1 . .49 (Kirby collages in FULL-COLOR) UNEARTHED . .54 (bootleg Kirby album covers) JACK KIRBY MUSEUM PAGE . .55 (visit & join www.kirbymuseum.org) GALLERY 2 . .56 (unused DC artwork) TRIBUTE . .64 (the 2011 Kirby Tribute Panel) GALLERY 3 . .78 (a go-go girl from SOUL LOVE) UNEARTHED . .88 (Kirby’s Someday Funnies) COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .90 PARTING SHOT . .100 Front cover inks: JOE SINNOTT Back cover inks: DON HECK Back cover colors: JACK KIRBY (an unused 1966 promotional piece, courtesy of Heritage Auctions) This issue would not have been If you’re viewing a Digital possible without the help of the JACK Edition of this publication, KIRBY MUSEUM & RESEARCH CENTER (www.kirbymuseum.org) and PLEASE READ THIS: www.whatifkirby.com—thanks! This is copyrighted material, NOT intended for downloading anywhere except our The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. -

(“Spider-Man”) Cr

PRIVILEGED ATTORNEY-CLIENT COMMUNICATION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY SECOND AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENSE AGREEMENT (“SPIDER-MAN”) CREATIVE ISSUES This memo summarizes certain terms of the Second Amended and Restated License Agreement (“Spider-Man”) between SPE and Marvel, effective September 15, 2011 (the “Agreement”). 1. CHARACTERS AND OTHER CREATIVE ELEMENTS: a. Exclusive to SPE: . The “Spider-Man” character, “Peter Parker” and essentially all existing and future alternate versions, iterations, and alter egos of the “Spider- Man” character. All fictional characters, places structures, businesses, groups, or other entities or elements (collectively, “Creative Elements”) that are listed on the attached Schedule 6. All existing (as of 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that are “Primarily Associated With” Spider-Man but were “Inadvertently Omitted” from Schedule 6. The Agreement contains detailed definitions of these terms, but they basically conform to common-sense meanings. If SPE and Marvel cannot agree as to whether a character or other creative element is Primarily Associated With Spider-Man and/or were Inadvertently Omitted, the matter will be determined by expedited arbitration. All newly created (after 9/15/11) characters and other Creative Elements that first appear in a work that is titled or branded with “Spider-Man” or in which “Spider-Man” is the main protagonist (but not including any team- up work featuring both Spider-Man and another major Marvel character that isn’t part of the Spider-Man Property). The origin story, secret identities, alter egos, powers, costumes, equipment, and other elements of, or associated with, Spider-Man and the other Creative Elements covered above. The story lines of individual Marvel comic books and other works in which Spider-Man or other characters granted to SPE appear, subject to Marvel confirming ownership. -

Spider-Woman Annual #1

AKASHA Non-Villain Antagonist Real Name: Occupation: Identity: Legal Status: Other Aliases: Place of Birth: Marital Status: Known Relatives: Group Affiliation: Base of Operations: First Post-Reboot Appearance: History: Height: Weight: Eyes: Hair: Uniform: Strength Level: Known Superhuman Powers: Other Abilities: Paraphernalia: points ST: HP: Speed: DX: Will: Move: IQ: Per: HT: FP: SM: 0 Dmg: BL: Dodge: Parry: DR: Attributes: Secondary Characteristics: Languages: English (Native) (Native Language) [0]. Cultural Familiarities: Western [0]. Advantages: Perks: Disadvantages: Quirks: Skills: Techniques: Starting Spending Money: Role-Playing Notes: ANGAR THE SCREAMER Villain Real Name: Occupation: Identity: Legal Status: Other Aliases: Place of Birth: Marital Status: Known Relatives: Group Affiliation: Base of Operations: First Post-Reboot Appearance: SENSATIONAL SPIDER- WOMAN # History: Height: Weight: Eyes: Hair: Uniform: Strength Level: Known Superhuman Powers: Other Abilities: Paraphernalia: points ST: HP: Speed: DX: Will: Move: IQ: Per: HT: FP: SM: 0 Dmg: BL: lbs. Dodge: Parry: DR: 0 Attributes: Secondary Characteristics: Languages: English (Native) (Native Language) [0]. Cultural Familiarities: Western [0]. Advantages: Perks: Disadvantages: Quirks: Skills: Techniques: Starting Spending Money: Role-Playing Notes: ARANEUS Hero Real Name: Occupation: Identity: Legal Status: Other Aliases: Place of Birth: Marital Status: Known Relatives: Group Affiliation: Base of Operations: First Post-Reboot Appearance: SENSATIONAL SPIDER-WOMAN ANNUAL #1. -

Avengers Dissemble! Transmedia Superhero Franchises and Cultic Management

Taylor 1 Avengers dissemble! Transmedia superhero franchises and cultic management Aaron Taylor, University of Lethbridge Abstract Through a case study of The Avengers (2012) and other recently adapted Marvel Entertainment properties, it will be demonstrated that the reimagined, rebooted and serialized intermedial text is fundamentally fan oriented: a deliberately structured and marketed invitation to certain niche audiences to engage in comparative activities. That is, its preferred spectators are often those opinionated and outspoken fan cultures whose familiarity with the texts is addressed and whose influence within a more dispersed film- going community is acknowledged, courted and potentially colonized. These superhero franchises – neither remakes nor adaptations in the familiar sense – are also paradigmatic byproducts of an adaptive management system that is possible through the appropriation of the economics of continuity and the co-option of online cultic networking. In short, blockbuster intermediality is not only indicative of the economics of post-literary adaptation, but it also exemplifies a corporate strategy that aims for the strategic co- option of potentially unruly niche audiences. Keywords Marvel Comics superheroes post-cinematic adaptations Taylor 2 fandom transmedia cult cinema It is possible to identify a number of recent corporate trends that represent a paradigmatic shift in Hollywood’s attitudes towards and manufacturing of big budget adaptations. These contemporary blockbusters exemplify the new industrial logic of transmedia franchises – serially produced films with a shared diegetic universe that can extend within and beyond the cinematic medium into correlated media texts. Consequently, the narrative comprehension of single entries within such franchises requires an increasing degree of media literacy or at least a residual awareness of the intended interrelations between correlated media products. -

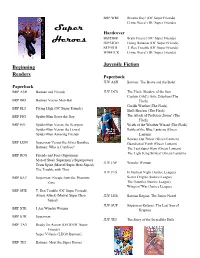

Super Heroes

BRP WRE Bizarro Day! (DC Super Friends) Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Super Hardcover B8555BR Brain Freeze! (DC Super Friends) Heroes H2934GO Going Bananas (DC Super Friends) S5395TR T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) W9441CR Crime Wave! (DC Super Friends) Juvenile Fiction Beginning Readers Paperback JUV ASH Batman: The Brave and the Bold Paperback BRP ASH Batman and Friends JUV DCS The Flash: Shadow of the Sun Captain Cold’s Artic Eruption (The BRP BRI Batman Versus Man-Bat Flash) Gorilla Warfare (The Flash) BRP ELI Flying High (DC Super Friends) Shell Shocker (The Flash) BRP FIG Spider-Man Saves the Day The Attack of Professor Zoom! (The Flash) BRP HIL Spider-Man Versus the Scorpion Wrath of the Weather Wizard (The Flash) Spider-Man Versus the Lizard Battle of the Blue Lanterns (Green Spider-Man Amazing Friends Lantern) Beware Our Power (Green Lantern) BRP LEM Superman Versus the Silver Banshee Guardian of Earth (Green Lantern) Batman: Who is Clayface? The Last Super Hero (Green Lantern) The Light King Strikes! (Green Lantern) BRP ROS Friends and Foes (Superman) Man of Steel: Superman’s Superpowers JUV JAF Wonder Woman Team Spirit (Marvel Super Hero Squad) The Trouble with Thor JUV JUS In Darkest Night (Justice League) BRP SAZ Superman: Escape from the Phantom Secret Origins (Justice League) Zone The Gauntlet (Justice League) Wings of War (Justice League) BRP SHE T. Rex Trouble (DC Super Friends) Aliens Attack (Marvel Super Hero JUV LER Batman Begins: The Junior Novel Squad) JUV SUP Superman Returns: The Last Son of BRP STE I Am Wonder