Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annotated Bibliography of Studies on Muslims in India

Studies on Muslims in India An Annotated Bibliography With Focus on Muslims in Andhra Pradesh (Volume: ) EMPLOYMENT AND RESERVATIONS FOR MUSLIMS By Dr.P.H.MOHAMMAD AND Dr. S. LAXMAN RAO Supervised by Dr.Masood Ali Khan and Dr.Mazher Hussain CONFEDERATION OF VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATIONS (COVA) Hyderabad (A. P.), India 2003 Index Foreword Preface Introduction Employment Status of Muslims: All India Level 1. Mushirul Hasan (2003) In Search of Integration and Identity – Indian Muslims Since Independence. Economic and Political Weekly (Special Number) Volume XXXVIII, Nos. 45, 46 and 47, November, 1988. 2. Saxena, N.C., “Public Employment and Educational Backwardness Among Muslims in India”, Man and Development, December 1983 (Vol. V, No 4). 3. “Employment: Statistics of Muslims under Central Government, 1981,” Muslim India, January, 1986 (Source: Gopal Singh Panel Report on Minorities, Vol. II). 4. “Government of India: Statistics Relating to Senior Officers up to Joint-Secretary Level,” Muslim India, November, 1992. 5. “Muslim Judges of High Courts (As on 01.01.1992),” Muslim India, July 1992. 6. “Government Scheme of Pre-Examination Coaching for Candidates for Various Examination/Courses,” Muslim India, February 1992. 7. National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), Department of Statistics, Government of India, Employment and Unemployment Situation Among Religious Groups in India: 1993-94 (Fifth Quinquennial Survey, NSS 50th Round, July 1993-June 1994), Report No: 438, June 1998. 8. Employment and Unemployment Situation among Religious Groups in India 1999-2000. NSS 55th Round (July 1999-June 2000) Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, September 2001. Employment Status of Muslims in Andhra Pradesh 9. -

Nt7458161216.Pdf

Sr. Name of Candidate Category Date of Birth Father’s /Husband Name Correspondence Address No. 1. T Sidharth Gen 18.07.1988 T Venkata Rao B9/S2, Floor – 3, Gali No – 7, Sewak Park, Uttam Nagar, Delhi – 110059 Chakravarty 2. Laxmi Yadav OBC 01.07.1981 Anil Kumar 55 Gali No – 19, Jain Road, Bhagwati Garden Ext., Uttam Nagar, Delhi – 110059 3. Arshpreet Singh Gen 30.10.1989 Jasbir Singh A-6/106 B, Janta Flats, Paschim Vihar, New Delhi – 110063 4. Pankaj Sharma Gen 01.10.1983 Rattan Chand Sharma 1267/5, Mohan Nagar, Kurukshetra – 136118 5. Deepak Kumar Gen 20.10.1986 Prem Chand Vill Bajera, P/O D Rubbal, Teh. Joginder Nagar, Dist. Mandi, Himachal Pradesh – 176123 6. Yogesh Kumar Gen 02.07.1992 Satya Prakash Pathak Shri Gandhi Seva Sadan, Lal Bag Bayana, Dist. Bharatpur, Rajasthan – 321401 7. Sunita Gen 26.03.1986 Dharamvir Singh WZ 93A, Uttam Nagar, Near Hastsal Road Gali No – 5&6, New Delhi- 110059 8. Shailpa Babbar OBC 19.02.1983 Mahender Singh Babbar 254 Teliwara, Shahdara, Delhi – 110032 9. Shilpa Gen 05.09.1987 Chander Prakash H No – 154, Type – III Multi Storey, Timar Pur, Delhi – 110054 10. Lalita Uniyal Gen 07.08.1985 Shankr Datt A-9/33, Dayalpur, Delhi – 110094 11. Rajneesh Kumar Gen 20.07.1987 Govind Lal Saxena Sharda University, Greater Noida, U.P – 201306 Saxena 12. Deepti Sikarwar Gen 03.12.1984 Laxman Singh Sikarwar 5/418, Shivani Homes Mahanadda Madan Mahal, Jabalpur, M.P – 482001 13. Binita Kumari OBC 10.02.1982 Ramvtar Yadav AT Maharna, PO Dharhara, PS Dharhara, Dist Munger – 811212 14. -

Castelist-Center.Pdf

म.प्र.रा煍य की पिछड व셍 ग जातियⴂ की क न्द्रीय सूची Entry No. Caste / Community Ahir, Brajwasi, Gawli, Gawali, Goli, Lingayat-Gaoli, Gowari, (Gwari), Gowra, Gawari, Gwara Jadav, Yadav, Raut 1 Thethwar, Gop/Gopal, Bargahi, Bargah 2 Asara 3 Bairagi Banjara, Kachiriwala Banjara, Laman Banjara, Bamania Banjara Laman/Lambani, Banjari, Mathura, Mathura Labhan, 4 Mathura Banjari, Navi Banjara, Jogi Banjara, Nayak, Naykada, Lambana/ Lambara Lambhani, Labhana, Laban, Labana, Lamne, Dhuriya 5 Barai, Waarai, Wari (Chaurasia), Tamoli, Tamboli Kumavatt, Kumavat, Bari 6 Barhai, Sutar, Suthar, Kunder, Vishwakarma 7 Vasudev, Basudeva, Basudev Vasudeva Harvola Kapdia Kapdi Gondhli 8 Badhbhuja, Bhunjwa, Bhurji, Dhuri or Dhoori 9 Bhat Charan (Charahm) Salwi, Sutiya Rav Jasondhi Maru-Sonia Chippa, Chhipa Bhavsar Nilgar, Jingar Nirali Ramgari Rangari Rangrez Rangarej Rangraz Rangredh Chippa-Sindhi- 10 Khatri Dhimar/ Dhimer, Bhoi, Kahar, Kahra, Dhiwar, Mallah, Nawda, Navda, Turaha, Kewat(Rackwar, Raikwar), Kir 11 (excluding Bhopal, Raisen & Sehore Districts) Britiya/ Vritiya, Sondhiya 12 Powar, Bhoyar/ Bhoyaar, Panwar 13 Bhurtiya, Bhutiya 14 Bhatiyara 15 Chunkar Chungar/Choongar Kulbandhiya Rajgir 16 Chitari 17 Darji Cheepi/Chhipi/Chipi Shipi Mavi (Namdev) Dhobi (excluding Bhopal, Raisen & Sehore District i.e. excluding the areas Where they are listed as Scheduled 18 Castes) 19 Deshwali, Mewati (excluding Sironj Tehsil of Vidisha District), Mina (Rawat) Deshwali 20 Kirar Kirad Dhakar/Dhakad Gadariya, Dhangar, Kurmar, Hatgar, Hatkar, Haatkaar, Gaadri, Gadaria, -

Gazette Government of Goa

REGD.GOA·5 Panaji, 20th January, 2000 (pausa 30, 1921) SERIES I No. 43 GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GOA NOTE: There are Five Extraordinary issues to the Official Gazette Government, to be filled through direct recruitment, in favour Series I No. 42 dated 13-/-2000 as/allows: of the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). In this regard the I) Extraordinmydated 14·1·2000jrom pages 587 to 588 common lists in respect of 26 StateslUTs have· been notified regarding Notification/rom Department ofPanchayat Raj vide Ministry of Welfare Resolutions No. 12011168/93-BCqC) and Coinmunity Development. dated the 10th S~ptember, 1993, No. 1201119/94-BCC 2) E.xtraordiflw),No. 2 dated 17-J-2000jrompages 589 to 590 dated the 19th October, 1994, No. 1201117/95-BCC dated the regarding Order from Department of Elections (State 24th May, 1995, No. 12011/96/94·BCC dated the 9th March. Election Commission). 1996, No. 12011/44/96-BCC dated 6th December, 1996, 3) ExtraordiIlQl:yNo. 3 dated 17-1 -20aO/rompages 59 J t0596 No. 1201 III 3/97-BCC dated 3rd December, 1997andNo.12011/ regarding Notificatiollfrom Department of Panchayat Raj /99/94-BCC dated 11th December, 1997. and Community Development (Dte. of Panchayats). 4) Extraordinw:vNo. 4dated 18-/ -20aO/rampages 597 to 598 2. The National Commission for Backward Classes was set regarding Notification/rom Department a/Transport up under the provision of the National Commission for 5) Extraordillal}' No.5 dated /9-1-2000 from pages 599 to Backward Classes Act, 1993 to entertain, examine and 600 ragarding Notijicationfrom Department ofPanchayat recommend upon the requests for inclusion and complaints Raj & Community Development (Die. -

Com. No. 3 List of Discrepancies in the Original Documents.Xlsx

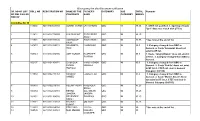

Discrepancy list after Document verification SR. NO OF LIST ROLL NO REGISTRATION NO NAME OF THE FATHER'S CATEGORY SUB TOTAL Remarks OF PML CALLED CANDIDATE NAME CATEGORY MARKS FOR DV Committee No. III 1 115502 92018103023382 SUMAN VERMAJAI KISHORE OBC Nil 86.25 1. CTET not qualified. 2. Spelling of Caste 'Soni' does not match with UT list. 2 111822 92018102718559 KHUSHWANT SATYABEER OBC Nil 86.25 SINGH 3 116001 92018101808534 AMANDEEP SHER SINGH OBC Nil 85.75 * See note at the end of list KAUR 4 120673 92018112130311 SANGEETA RAMNIWAS OBC Nil 85.5 1. Category changed from OBC to RANI General. 2. Caste 'Goswami' doest not exist in UT list. 5 109243 92018102414995 AMIT KUMAR RAJENDER OBC Nil 85.5 1. Caste 'Jangra Bramin' does not exist in SHARMA UT list.. 2. Category changed from OBC to General. 6 102497 92018101304974 SITENDER NAND KISHOR OBC Nil 85.5 1. Category changed from OBC to KUMAR ROHILLA General. 2. Caste 'Rohilla' doest not exist ROHILLA in UT list.3. CTET not clear in General Category. (89/150) 7 111989 92018102718763 NASEEM LIAQUAT ALI OBC Nil 85.5 1. Category changed from OBC to AHMED General. 2. Caste 'Momin Ansari' doest not exist in UT list.3. CTET not clear in General Category. (89/150) 8 105889 92018102010168 REENA YADAV RAJENDER OBC Nil 85.25 SINGH 9 106354 92018102010853 REKHA DAL SINGH OBC Nil 85.25 JANGRA JANGRA 10 102052 92018101304566 DEVENDER RAM PHUL OBC Nil 85.25 SINGH 11 117171 92018111325383 RAKESH OM DUTT OBC Nil 85.25 KUMAR 12 112933 92018102820004 PRIYANKA JAI PAL OBC Nil 85 * See note at the end of list 13 104795 92018101808561 MAN MOHAN KAILASH OBC Nil 85 CHANDER Discrepancy list after Document verification SR. -

147 Statement

Inclusion of castes in OBC list 3293. SHRI D. RAJA: SHRI R.C. SINGH: Will the Minister of SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT be pleased to state: (a) whether Government is considering a proposal to include 64 castes from Chhattisgarh and 121 from Jharkhand in the Central OBC list; and (b) if so, the details thereof? THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT (SHRI D. NAPOLEON): (a) Castes/sub castes/synonyms have been notified in the Central list of OBCs for the States of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand vide notification dated 18.08.2010. (b) A Statement is enclosed. Statement Details of the Castes/sub castes/synonyms notified in the Central list of OBCs for the States of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand Chhattisgarh New Entry Name of Caste/sub castes/synonyms, etc. No. 1 2 1. Ahir, Brajwasi, Gawli, Gawali, Goli, Lingayat-Gaoli, Gowari (Gwari), Gowra, Gawari, Gwara, Jadav, Yadav, Raut, Thethwar, Gop/ Gopal. 2. Asara 3. Badhbhuja, Bhurji, Dhuri or Dhoori 4. Bairagi 5. Banjara, Kachiriwala Banjara, Laman Banjara, Bamania Banjara, Laman/Lambani, Banjari Mathura, Mathura Labhan, Mathura Banjari, Navi Banjara, Jogi Banjara, Nayak, Naykada, Lambana/Lambara, Lambhani, Labhana, Laban, Labana, Lamne, Dhuriya 6. Barai, Waarai, Wari (Chaurasia), Tamoli, Tamboli, Kumavatt, Kumavat 7. Barhai, Sutar, Suthar, Kunder, Vishwakarma 8. Bharood 9. Bhat, Charan (Charahm), Sawli, Sutiya, Rav, Jasondhi, Maru-Sonia 147 1 2 10. Bhatiyara 11. Bhurtiya, Bhutiya 12. Chippa, Chhipa, Bhavsar, Nilgar, Jingar, Nirali, Ramgari, Rangari, Rangrez, Rangarej, Rangraz, Rangredh, Chippa-Sindhi-Khatri 13. Chitari 14. Chunkar, Chungar/Choongar, Kulbandhiya, Rajgir 15. Dangi 16. Darji, Cheepi/Chhipi/Chipi, Shipi, Mavi (Namdev) 17. -

Regime Type and Women's Substantive Representation in Pakistan: a Study in Socio Political Constraints on Policymaking

REGIME TYPE AND WOMEN’S SUBSTANTIVE REPRESENTATION IN PAKISTAN: A STUDY IN SOCIO POLITICAL CONSTRAINTS ON POLICYMAKING PhD DISSERTATION Submitted by Naila Maqsood Reg. No. NDU-GPP/Ph.D-009/F-002 Supervisor Dr. Sarfraz Hussain Ansari Department of Government & Public Policy Faculty of Contemporary Studies National Defence University Islamabad 2016 REGIME TYPE AND WOMEN’S SUBSTANTIVE REPRESENTATION IN PAKISTAN: A STUDY IN SOCIO POLITICAL CONSTRAINTS ON POLICY MAKING PhD DISSERTATION Submitted by Naila Maqsood Reg. No. NDU-GPP/Ph.D-009/F-002 This Dissertation is submitted to National Defence University, Islamabad in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government and Public Policy Supervisor Dr. Sarfraz Hussain Ansari Department of Government & Public Policy Faculty of Contemporary Studies National Defence University Islamabad 2016 Certificate of Completion It is hereby recommended that the dissertation submitted by Ms. Naila Maqsood titled “Regime Type and Women’s Substantive Representation in Pakistan: A Study in Socio-Political Constraints on Policymaking” has been accepted in the partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the discipline of Government & Public Policy. __________________________________ Supervisor __________________________________ External Examiner Countersigned By: …………………………………………… …………………………………….. Controller Examination Head of department Supervisor’s Declaration This is to certify that PhD dissertation submitted by Ms. Naila Maqsood titled “Regime Type and Women’s Substantive Representation in Pakistan: A Study in Socio-Political Constraints on Policymaking” is supervised by me, and is submitted to meet the requirements of PhD degree. Date: _____________ Dr. Sarfraz Hussain Ansari Supervisor Scholar’s Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis submitted by me titled “Regime Type and Women’s Substantive Representation in Pakistan: A Study in Socio- Political Constraints on Policymaking” is based on my own research work and has not been submitted to any other institution for any other degree. -

Looms Found Using Child Labour State: Uttar Pradesh

Looms Found Using Child Labour State: Uttar Pradesh S. Loom Owner Vill/ Name of the Child Labour Type of Loom Owner’s Name Post Pin Block/ULB Tehsil Dist. State Reg. No. Period of Inspection No. Father's Name Mohalla Child Labour Father's Name Work 1 Patiraj Harijan Late Pancham Barigaon Aurai Aurai Aurai Bhadohi Uttar Pradesh Not Registered Arun Arjun Weaving April, 2013 to June, 2013 2 Kariya Bind Late Ganda Chandel Dandiya Kon (Chilh) Kon (Chilh Mirzapur Mirzapur Uttar Pradesh Not Registered Jai Prakash Ajeet Kumar Weaving April, 2013 to June, 2013 1. Mohd. Riyaz 1. Azam 2. Mohd. Rafiq 3 Prakash Maurya Lakhan Maurya Amrauna Nayee Bazar Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Uttar Pradesh Not Registered 2. Mushtak Weaving April, 2013 to June, 2013 3. Mohd. Samsuddin 3.Mushtak 4. Mohd. Khurshid 1. Mahmad 1. Ahmad Navir 4 Suhail Nadeem Ansari Amrauna Nayee Bazar Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Uttar Pradesh Not Registered 2. Intezar 2. Ayyas Weaving April, 2013 to June, 2013 3. Salamat 3.Mansoor 1. Hasnain 1. Mohd. Ali 5 Laxmi Shankar Magru Maurya Sahbabadpur Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Uttar Pradesh Not Registered Weaving April, 2013 to June, 2013 2. Salma 2. Mohd. Ali 1. Vipin 1. Ram Aasre 6 Nanhaku Bind Babau Ghamahapur Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Uttar Pradesh Not Registered Weaving April, 2013 to June, 2013 2. Subalak 2. Suraj Kumar 1. Mustakim 7 Ram Sevak Yadav Dagar Ram Yadav Gharvanpur Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Uttar Pradesh Not Registered 2. Yashim Weaving April, 2013 to June, 2013 3. Bahruddin 1. Vijay 1. Tanka Adhikari 8 Aasim Parvez Anwar Ahmad Jalalpur Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Bhadohi Uttar Pradesh 281147 Weaving April, 2013 to June, 2013 2. -

Oc Caste List in Telangana Pdf

Oc caste list in telangana pdf Continue This is a complete list of Muslim communities in India (OBCs) that are recognized in the Indian Constitution as other backward classes, a term used to classify socially and educationally disadvantaged classes. The central list of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana below is a list of Muslim communities to which the Indian government has granted status to other backward classes in the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Casta/Community Resolution No. and date No. 37 Mehtar 12011/68/93-BCC (C ) dt. September 10, 1993 and 12011/9/2004-BCC dt. 16 January 2006 No43 Dudekula Laddaf, Pinjari or Nurbash (Muslim) 12011/68/93-BCC (C ) dt. 10 September 1993 No62 Arekatika, Katika, Kuresh (Muslim butchers) 12011/68/93-BCC (C ) dt. September 10, 1993 and 12011/4/2002-BCC dt. 13 January 2004 No33 (Muslim Butchers) 12011/68/93-BCC (C ) dt. September 10, 93 and 12011/4/2002-BCC dt. On 13 January 2004, the State list lists the following list of Muslim communities to which the Andhra Pradesh State Government and the Karnataka State Government have granted the status of other backward classes. [4] 1. Achukattalawndlu, Singali, Sinhamvallu, Achupanivallu, Achukattuwaru, Achukatlawandlu. 2. Attar Saibulu, Attarollo 3. Dhobi Muslim / Muslim Dhobi / Dhobi Musalman, Turka Chakla or Turka Sakala, Turaka Chakali, Tulukka Vannan, Tsakalas, Sakalas or Chakalas, Muslim Rajakas 4. Alvi, Alvi Sayyen, Shah Alvi, Alvi, Alvi Sayed, Darvesh, Shah 5. Garadi Muslim, Garadi Saibulu, Pamulavallu, Kani-Kattuvalla, Garadoll, Garadig 6. Gosangi Muslim, Faker Sayebulu 7. Guddy Eluguvallu, Elugu Bantuvall, Musalman Kilu Gurralavalla 8. -

The Gazette of India

REGD. NO. D. L.-33004/99 The Gazette of India EXTRAORDINARY PART I—Section 1 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 241 ] NEW DELHI. WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 27. 1999/KARTIKA 5,1921 3177 GI/99 -l (I) 2 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART I—SEC. 1 ] 3 4 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART I—SEC. 1 ] 5 6 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART I—SEC. 1] 7 8 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART I—SEC. 1 ] 9 3177/GI/99-2. 10 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA: EXTRAORDINARY [PART I—SEC. 1 ] 11 12 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA EXTRAORDINARY [PART I—SEC. 1] 13 MINISTRY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE & EMPOWERMENT RESOLUTION New Delhi, the 27th October, 1999 No. 12011/68/98-BCC.—The Government of India, vide the Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pension (Department of Personnel and Training) OM No. 36012/22/93-Estt. (SCT), dated the 8th September, 1993, have reserved 27% of vacancies in Civil posts and services under the Central Government, to be filled through direct recruitment, in favour of the Other Backward Classes (OBCs), In this regard the common lists in respect of 26 States/ UTs have been notified vide Ministry of Welfare Resolutions No. 12011/68/93 -BCC(C) dated the 10th September, 1993, No. 12011/9/94-BCC dated the 19th October, 1994, No. 12011/7/95-BCC dated the 24th May, 1995, No. 12011/96/94- BCC dated the 9th March, 1996, No. 12011/44/96-BCC dated 6th December, 1996, No. 12011/13/97-BCC dated 3rd December, 1997 and No. -

Does Caste Play a Political Role Among Muslims in India? Julien Levesque

Does caste play a political role among Muslims in India? Julien Levesque To cite this version: Julien Levesque. Does caste play a political role among Muslims in India?. GIS Asie, 2021. hal- 03196813 HAL Id: hal-03196813 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03196813 Submitted on 21 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Does caste play a political role among Muslims in India? Julien Levesque GIS Asie, article of the month, April 2021 http://www.gis-reseau-asie.org/en/does-caste-play-political-role-among-muslims-india Keywords: minority politics, associations, Islam, caste, India figure 1: Muslim pilgrims pray facing the tomb of the Sufi saint Muinuddin Chishti, in the city of Ajmer in Rajasthan. Sufi saints and their descendant claim to descend from Prophet Muhammad, and are thus designated as “sayyid”, the name of group that generally tops the symbolic social hierarchy. Photo credit: Julien Levesque South Asian Muslims represent more than 500 million people, which is more than a quarter of the world’s Muslim population, mainly located in Pakistan (220 million), India (200 million), and Bangladesh (150 million). -

CENTRAL LIST of Obcs for the STATE of CHHATISGARH

CENTRAL LIST OF OBCs FOR THE STATE OF CHHATISGARH Entry No Caste/ Community Resolution No. & Date Ahir, 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Brajwasi, Gawli, Gawali, Goli, Lingayat-Gaoli, Gowari 1. (Gwari), Gowra, Gawari, Gwara, Jadav, Yadav, Raut, Thethwar, Gop/Gopal 2. Asara 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Badhbhuja, Bhunjwa, Bhurji, Dhuri or 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 3. Dhoori 12015/13/2010-B.C.II. Dt. 08/12/2011 4. Bairagi 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Banjara, 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Kachiriwala Banjara, Laman Banjara, Bamania Banjara, Laman/Lambani, Banjari Mathura, Mathura Labhan, 5. Mathura Banjari, Navi Banjara, Jogi Banjara, Nayak, Naykada Lambana/Lambara Lambhani, Labhana Laban, Labana, Lamne, Dhuriya Barai 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Waarai Wari (Chaurasia) 6. Tamoli Tamboli Kumavatt, Kumavat Barhai, Sutar, Suthar, Kunder, 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 7. Vishwakarma 8. Bharood 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Bhat 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Charan (Charahm) Sawli, Sutiya 9. Rav Jasondhi Maru-Sonia 10. Bhatiyara 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Bhurtiya 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 11. Bhutiya 1 Chippa, Chhipa 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Bhavsar Nilgar Jingar Nirali Ramgari 12. Rangari Rangrez Rangarej Rangraz Rangredh Chippa-Sindhi-Khatri 13. Chitari 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Chunkar 12015/2/2007-BCC dt. 18/08/2010 Chungar/Choongar 14. Kulbandhiya Rajgir 15. Dangi 12015/2/2007-BCC dt.