Panel Discussion: Global Reality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED by FOXTEL All Nominees – by Category FEATURE FILM

2019 AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED BY FOXTEL All Nominees – by Category FEATURE FILM AACTA AWARD FOR BEST FILM PRESENTED BY FOXTEL HOTEL MUMBAI Basil Iwanyk, Gary Hamilton, Julie Ryan, Jomon Thomas – Hotel Mumbai Double Guess Productions JUDY & PUNCH Michele Bennett, Nash Edgerton, Danny Gabai – Vice Media LLC, Blue-Tongue Films, Pariah Productions THE KING Brad Pitt, Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, Liz Watts, David Michôd, Joel Edgerton – Plan B Entertainment, Porchlight Films, A Yoki Inc, Blue-Tongue Films THE NIGHTINGALE Kristina Ceyton, Bruna Papandrea, Steve Hutensky, Jennifer Kent – Causeway Films, Made Up Stories RIDE LIKE A GIRL Richard Keddie, Rachel Griffiths, Susie Montague – The Film Company, Magdalene Media TOP END WEDDING Rosemary Blight, Kylie du Fresne, Kate Croser – Goalpost Pictures AACTA AWARD FOR BEST INDIE FILM PRESENTED BY EVENT CINEMAS ACUTE MISFORTUNE Thomas M. Wright, Virginia Kay, Jamie Houge, Liz Kearney – Arenamedia, Plot Media, Blackheath Films BOOK WEEK Heath Davis, Joanne Weatherstone – Crash House Productions BUOYANCY Rodd Rathjen, Samantha Jennings, Kristina Ceyton, Rita Walsh – Causeway Films EMU RUNNER Imogen Thomas, Victor Evatt, Antonia Barnard, John Fink – Emu Runner Film SEQUIN IN A BLUE ROOM Samuel Van Grinsven, Sophie Hattch, Linus Gibson AACTA AWARD FOR BEST DIRECTION HOTEL MUMBAI Anthony Maras – Hotel Mumbai Double Guess Productions JUDY & PUNCH Mirrah Foulkes – Vice Media LLC, Blue-Tongue Films, Pariah Productions THE KING David Michôd – Plan B Entertainment, Porchlight Films, A Yoki Inc, -

ABC TV 2015 Program Guide

2014 has been another fantastic year for ABC sci-fi drama WASTELANDER PANDA, and iview herself in a women’s refuge to shine a light TV on screen and we will continue to build on events such as the JONAH FROM TONGA on the otherwise hidden world of domestic this success in 2015. 48-hour binge, we’re planning a range of new violence in NO EXCUSES! digital-first commissions, iview exclusives and We want to cement the ABC as the home of iview events for 2015. We’ll welcome in 2015 with a four-hour Australian stories and national conversations. entertainment extravaganza to celebrate NEW That’s what sets us apart. And in an exciting next step for ABC iview YEAR’S EVE when we again join with the in 2015, for the first time users will have the City of Sydney to bring the world-renowned In 2015 our line-up of innovative and bold ability to buy and download current and past fireworks to audiences around the country. content showcasing the depth, diversity and series, as well programs from the vast ABC TV quality of programming will continue to deliver archive, without leaving the iview application. And throughout January, as the official what audiences have come to expect from us. free-to-air broadcaster for the AFC ASIAN We want to make the ABC the home of major CUP AUSTRALIA 2015 – Asia’s biggest The digital media revolution steps up a gear in TV events and national conversations. This year football competition, and the biggest football from the 2015 but ABC TV’s commitment to entertain, ABC’s MENTAL AS.. -

Goldsmith, Ben (2015) Bad Eggs

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Goldsmith, Ben (2015) Bad Eggs. In Ryan, M, Lealand, G, & Goldsmith, B (Eds.) Directory of World Cinema: Australia and New Zealand 2. Intellect Ltd, United Kingdom, pp. 82-83. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/81223/ c Copyright 2015 Intellect This work is covered by copyright. Unless the document is being made available under a Creative Commons Licence, you must assume that re-use is limited to personal use and that permission from the copyright owner must be obtained for all other uses. If the docu- ment is available under a Creative Commons License (or other specified license) then refer to the Licence for details of permitted re-use. It is a condition of access that users recog- nise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. If you believe that this work infringes copyright please provide details by email to [email protected] Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.intellectbooks.co.uk/ books/ view-Book,id=4951/ Pre-publication draft of chapter in Ben Goldsmith, Mark David Ryan and Geoff Lealand (eds) Directory of World Cinema: Australia and -

{PDF EPUB} Phaic Tan Sunstroke on a Shoestring by Santo

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Phaic Tăn Sunstroke on a Shoestring by Santo Cilauro Phaic Tăn. Phaic Tăn (subtitled Sunstroke on a Shoestring ) is a parody travel guidebook examining imaginary country Phaic Tăn. The book was written by Australians Tom Gleisner, Santo Cilauro, and Rob Sitch. It is the effective sequel to Molvanîa which was also published by Jetlag Travel and written by Tom Gleisner, Santo Cilauro, and Rob Sitch. Contents. About Phaic Tăn. The Kingdom of Phaic Tăn is a composite creation of a number of stereotypes and clichés about Southeast Asian countries. Phaic Tăn is said to be situated in Southeast Asia. Place names in Phaic Tăn initially seem to be Vietnamese or Thai, but they form English language puns, hence the capital is called "Bumpattabumpah" ("bumper to bumper"). "Phaic Tăn" can be read as "Fake Tan". Also, the districts are the mountainous "Pha Phlung" ("far flung"), the infertile "Sukkondat" ("suck on that"), the hyper "Buhng Lunhg" ("bung lung"; Australian slang 'bung', meaning 'failed'), and the exotic "Thong On". The country was formerly a colony of France, but was liberated in the early 20th century through student and Communist uprisings. A Marxist dictatorship under Chau Quoc continued until his death in 1947, which prompted the country to launch into a lengthy civil war. Eventually a CIA- backed coup ("Operation Freedom") made the country into a military dictatorship which it remains to this day. The country has a popular royal family, though the current king has been deposed no less than 25 times. Like Molvanîa , the humor of the book comes from the guide's attempts to present Phaic Tăn as an attractive, enjoyable country when it is really little more than a squalid, third-world dump. -

The D-Generation the Satanic Sketches Mp3, Flac, Wma

The D-Generation The Satanic Sketches mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Non Music Album: The Satanic Sketches Country: Australia Released: 1989 Style: Comedy MP3 version RAR size: 1349 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1746 mb WMA version RAR size: 1162 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 932 Other Formats: AC3 MOD DMF DTS AHX RA VOC Tracklist 1 The Satanic Sketches 1:03:05 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Metropolis Audio Made By – Disctronics B Credits Bass – Roger McLachlan Cover – Mushroom Art Drums – Angus Burchall Engineer – Neno Valka Engineer [Assistant] – Rodney Lowe Engineer [Engineer on Five In A Row] – Ross Cockle Featuring – John Brown Guitar – Jack Jones Performer [Original Music] – Colin Setches, John Grant Producer – Phil Simon Producer [Producer on Five In A Row] – Colin Setches, Phil Simon Vocals – Jack Jones , Jane Kennedy Voice Actor – John Harrison, Magda Szubanski, Marg Downey, Michael Veitch, Phil Simon, Rob Sitch, Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner, Tony Martin Written-By – Michael Veitch, Rob Sitch, Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner, Tony Martin Notes Release consists of a single track made of various comedy skits. Recorded at Metropolis Audio, Melbourne Australia. Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year The Satanic The D- L30223 Sketches (LP, Mushroom L30223 Australia 1989 Generation Album) The D- The Satanic C 30223 Mushroom C 30223 Australia 1989 Generation Sketches (Cass) The Satanic D30223, The D- Mushroom, D30223, Sketches (CD, Australia 1998 MUSH32065.2 Generation Mushroom MUSH32065.2 Album, RE) Related Music albums to The Satanic Sketches by The D- Generation Michael Spiby - Ho's Kitchen Robbie Williams - Swing When You're Winning John Lennon - Imagine - Music From The Motion Picture John Farnham - age of reason Phil York & Colin Barratt - Knowledge Is Power Phil Potter - The Restorer Champion Doug Veitch - The Original Phil Collins - Face Value Phil Keaggy - Crimson And Blue Frente! - Labour Of Love. -

YEAR in REVIEW Celebrating Australian Screen Success and a Record Year for AFI | AACTA YEAR in REVIEW CONTENTS

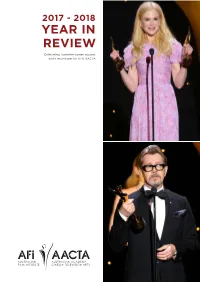

2017 - 2018 YEAR IN REVIEW Celebrating Australian screen success and a record year for AFI | AACTA YEAR IN REVIEW CONTENTS Welcomes 4 7th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel 8 7th AACTA International Awards 12 Longford Lyell Award 16 Trailblazer Award 18 Byron Kennedy Award 20 Asia International Engagement Program 22 2017 Member Events Program Highlights 27 2018 Member Events Program 29 AACTA TV 32 #SocialShorts 34 Meet the Nominees presented by AFTRS 36 Social Media Highlights 38 In Memoriam 40 Winners and Nominees 42 7th AACTA Awards Jurors 46 Acknowledgements 47 Partners 48 Publisher Australian Film Institute | Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts Design and Layout Bradley Arden Print Partner Kwik Kopy Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this publication. The publisher does not accept liability for errors or omissions. Similarly, every effort has been made to obtain permission from the copyright holders for material that appears in this publication. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. Comments and opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of AFI | AACTA, which accepts no responsibility for these comments and opinions. This collection © Copyright 2018 AFI | AACTA and individual contributors. Front Cover, top right: Nicole Kidman accepting the AACTA Awards for Best Supporting Actress (Lion) and Best Guest or Supporting Actress in a Television Drama (Top Of The Lake: China Girl). Bottom Celia Pacquola accepting the AACTA Award for Best right: Gary Oldman accepting the AACTA International Award for Performance in a Television Comedy (Rosehaven). Best Lead Actor (Darkest Hour). YEAR IN REVIEW WELCOMES 2017 was an incredibly strong year for the Australian Academy and for the Australian screen industry at large. -

Make a Date with Melbourne!

MAKE A DATE WITH MELBOURNE! 5 Steps to a Great Theatrical Escape in Melbourne MELBOURNE, 26 MAY 2014— Melbourne Theatre Company has made getting to the theatre in Melbourne a whole lot easier with the launch of its new website makeadatewithmelbourne.com.au. Bringing together MTC shows, nearby accommodation and dining, travel and other attractions, makeadatewithmelbourne.com.au is a great new way to plan a big night out or weekend in Melbourne. “MTC is Victoria’s flagship theatre company, a leading light in the state’s cultural tourism crown. With Victoria Australia’s top cultural destination and Melbourne the most popular domestic holiday destination in the country, we want people to think MTC when planning their visit,” said MTC Executive Director Virginia Lovett. “Melbourne is a great theatre city and, like preparing to visit New York and London, ‘What shows am I going to see?’ ought to sit right alongside ‘Where am I going to stay?’ and ‘Where do I start shopping?’ We’re onstage all year round, so, if you already come to a show once a year, it’s now even easier to come more often. And if you’ve never made a great theatrical escape, now’s the time to grab a friend, go through the five easy steps, and make a date with Melbourne,” said Ms Lovett. MTC’s 2014 season offers numerous reasons to see a show in the coming months: Offspring’s Linda Cropper and musical theatre favourite Philip Quast provide the star power for Ghosts, Ibsen’s haunting revelation of family secrets, now playing until 21 June Comedy gets airborne with The Speechmaker -

Representations of Troubled and Troubling Masculinities in Some Australian Films, 1991-2001

‘Gods in our own World’: Representations of Troubled and Troubling Masculinities in Some Australian Films, 1991-2001 Shane Crilly Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Discipline of English Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences University of Adelaide April 2004 Table of Contents Abstract iii Declaration iv Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter 1 A Man’s World: Boys, their Fathers and the Reproduction of the Patriarchy 24 Chapter 2 Mummy’s Boys: Men, their Mothers and Absent Fathers 53 Chapter 3 Bad Boys: Representations of Men’s Violence in The Boys 86 Chapter 4 The Performance of Masculinity: Larrikinism and Australian Masculinities 119 Chapter 5 Love, Sex, Marriage, and Sentimental Blokes 155 Conclusion 197 Filmography 209 Bibliography 211 Abstract The dominance of male characters in Australian films makes our national cinema a rich resource for the examination of the construction of masculinities. This thesis argues that the codes of the hegemonic masculinities in capitalist patriarchal societies like Australia insist on an absolute masculine position. However, according to Oedipal logic, this position always belongs to another man. Masculine yet ‘feminised,’ identity is fraught with anxiety but sustained by the ‘dominant fiction’ that equates the penis with the phallus and locates the feminine as its polar opposite. This binary relationship is inaugurated in childhood when a boy must distinguish his identity from his mother, who, significantly, is a different gender. Being masculine means not being feminine. However, as much as men strive towards inhabiting the masculine position completely, this masquerade will always be exposed by the elements associated with femininity that are an inevitable part of the human experience. -

2020 AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED by FOXTEL First Round Nominees – by Category TELEVISION

2020 AACTA AWARDS PRESENTED BY FOXTEL First Round Nominees – by Category TELEVISION AACTA AWARD FOR BEST DRAMA SERIES • BLOOM David Maher, David Taylor, Glen Dolman, Sue Seeary—Playmaker Media (Stan) • DOCTOR DOCTOR Ian Collie, Ally Henville, Keith Thompson, Rodger Corser—Easy Tiger (Nine Network) • HALIFAX: RETRIBUTION Roger Simpson, Louisa Kors—Beyond Lone Hand (Nine Network) • THE HEIGHTS Warren Clarke, Peta Astbury-Bulsara, Debbie Lee, Que Minh Luu— Matchbox Pictures in association with For Pete’s Sake Productions (ABC) • MYSTERY ROAD David Jowsey, Greer Simpkin—Bunya Productions (ABC) • WENTWORTH Jo Porter, Pino Amenta—Fremantle (Foxtel) AACTA AWARD FOR BEST TELEFEATURE OR MINISERIES • THE GLOAMING Victoria Madden, John Molloy, Fiona McConaghy—2 Jons and Sweet Potato Films (Stan) • HUNGRY GHOSTS Stephen Corvini, Timothy Hobart, Debbie Lee, Sue Masters— Matchbox Pictures (SBS) • OPERATION BUFFALO Vincent Sheehan, Tanya Phegan, Peter Duncan—Porchlight Films (ABC) • THE SECRETS SHE KEEPS Helen Bowden, Jason Stephens, Paul Watters—Lingo Pictures (Network Ten) • STATELESS Cate Blanchett, Elise McCredie, Tony Ayres, Sheila Jayadev, Paul Ranford, Liz Watts, Andrew Upton—Matchbox Pictures, Dirty Films (ABC) AACTA AWARD FOR BEST COMEDY SERIES • AT HOME ALONE TOGETHER Nick Hayden, Janet Gaeta, Nikita Agzarian, Dan Ilic— Australian Broadcasting Company (ABC) • BLACK COMEDY Kath Shelper, Mark O’Toole, Nakkiah Lui, David Woodhead—Scarlett Pictures (ABC) • THE OTHER GUY Angie Fielder, Polly Staniford, Jude Troy, Alice Willison—Aquarius Films, -

ABC Sweeps 7Th AACTA Awards with Seven Wins

RELEASED: Wednesday 6th December ABC sweeps 7th AACTA Awards with seven wins A staggering five ABC programs won their category at the 7th AACTA Awards ceremony this week in Sydney. The ABC wishes to congratulate all the nominees and winners whose vision and talents contribute to the extraordinarily strong TV industry in Australia. Seven Types of Ambiguity, ABC’s critically acclaimed drama series, swept the categories for television winning three out of a potential five AACTA Awards. Awards included Best Direction in a Television Drama or Comedy, Best Cinematography in Television and Best Editing in Television. The AACTA Award for Best Television Comedy Series went to Utopia for the second time, having previously received the Award at the 4th AACTA Awards. David Anderson, Director of Television, ABC TV said: “The ABC congratulates our 2017 AACTA’s winners, seven wins is an excellent result. These successes are a testament to the rich and diverse range of content we offer our audience, and the investment the ABC makes in commissioning quality Australian content. I look forward to further success with our 2018 programming slate.” 7th AACTA Awards for ABC Titles AACTA AWARD FOR BEST TELEVISION COMEDY SERIES WINNER – UTOPIA Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner, Rob Sitch, Michael Hirsh – ABC AACTA AWARD FOR BEST CHILDREN’S TELEVISION SERIES WINNER – LITTLE LUNCH – THE SPECIALS Robyn Butler, Wayne Hope – ABC AACTA AWARD FOR BEST DIRECTION IN A TELEVISION DRAMA OR COMEDY WINNER - SEVEN TYPES OF AMBIGUITY Episode 2 – Alex Glendyn Ivin – ABC AACTA AWARD -

Better Performed Yet Uneasy to Say Upturn

The Export-Import Bank of China: Want to Be the Best in A Better World ? China’s Economy in H1: Better Performed Yet Uneasy to Say Upturn 邮发代号:80-799 国内刊号:CN11-1020/F 国际刊号:ISSN0009-4498 Jiangxi Changhe Motors Co.,Ltd. I. The introduction of Changhe Motors Established on Nov. 26, 1999, Jiangxi Changhe Motors Co.,Ltd. is located in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi prov- ince, the famous city of China. It was sanctioned by National Economic and Trade Committee, Changhe Air- craft Industries Group is the main sponsor. Jiangxi Changhe Motors Co., Ltd. (Changhe Motors) is one of the leading motor manufacturers, and the R&D and production base of small emission autos. The first microbus of China was manufactured here. Changhe Motors has 6000 employees, with the registered capital of RMB 410 million. It has three bases of finished car manufacturing, including Jingdezhen, Jiujiang and Hefei, one engine manufacturing base in Jiujiang, and a industrial park of auto parts production. With a production pattern of crossing over two prov- inces and three cities, the company has developed an annual production capacity of 300,000 finished cars and 150,000 auto engines. The company covers a wide business range of the series of mini cars, the design, development, manufac- ture, sales, aftersales services for economic vehicles, and the development, consultation and services of the relevant projects. The company adheres to the concept of “Striving for the mission of letting cars drive into the average families”. The company is devoted to the mission of boosting China’s auto industry, making great contribu- tions to the clients, shareholders and the society with the highest quality. -

AACTA Award Winners Announced in Sydney As Australia's Top Film And

Media Release – Strictly embargoed until 8:45pm Wednesday 9 December 2015 AACTA Award Winners Announced in Sydney as Australia’s top Film and TV stars sHine on Seven WatcH tHe show on Channel Seven, 8:30pm tonight Australia’s top film and television talent came together tonight to honour Australia’s best screen achievements of 2015 at the 5th AACTA Awards Ceremony presented by Presto, held at The Star Event Centre in Sydney. Broadcast on Channel Seven at 8:30pm tonight, show presenters include Patrick Brammall, Mel Gibson, RadHa MitcHell, Daniel MacPHerson, StepHen Peacocke, Erik Thomson and Megan Gale, along with HOME AND AWAY’s Georgie Parker and Bonnie Sveen, to name just a few. The red carpet sizzled, with guests and nominees attending including George Miller, AntHony LaPaglia, Hugo Weaving, RacHael GriffitHs, Ryan Corr, Margaret Pomeranz, Marta Dusseldorp, AleXandra Schepisi, Natalie Bassingthwaighte, SamantHa Harris and Bindi Irwin, along with a number of HOME AND AWAY cast members. Among the show highlights was the presentation of Australia’s highest screen accolade, the AACTA Longford Lyell Award, to performer Cate Blanchett, who received tributes from some of the world’s biggest names in film, including Martin Scorsese, Alejandro González Iñárritu, Robert Redford, Ridley Scott and Ron Howard. The show’s musical acts were outstanding, with Justice Crew featuring in the show opener, and performances by Birds of Tokyo, Rudimental and this year’s winner of THE X FACTOR, Cyrus. Tune in to see all the glamour of the red carpet, and to watch Australia’s top performers, practitioners and productions honoured at 8:30pm tonight on Channel Seven.