Targeting Cyst Initiation in ADPKD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emerging Landscape of Dynamic DNA Methylation in Early Childhood

The emerging landscape of dynamic DNA methylation in early childhood Cheng-Jian Xu, Marc Jan Bonder, Cilla Söderhäll, Mariona Bustamante, Nour Baïz, Ulrike Gehring, Soesma Jankipersadsing, Pieter van der Vlies, Cleo van Diemen, Bianca van Rijkom, et al. To cite this version: Cheng-Jian Xu, Marc Jan Bonder, Cilla Söderhäll, Mariona Bustamante, Nour Baïz, et al.. The emerg- ing landscape of dynamic DNA methylation in early childhood. BMC Genomics, BioMed Central, 2017, 18, pp.25. 10.1186/s12864-016-3452-1. hal-01792686 HAL Id: hal-01792686 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01792686 Submitted on 26 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Xu et al. BMC Genomics (2017) 18:25 DOI 10.1186/s12864-016-3452-1 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access The emerging landscape of dynamic DNA methylation in early childhood Cheng-Jian Xu1,2*, Marc Jan Bonder2, Cilla Söderhäll3,4, Mariona Bustamante5,6,7,8, Nour Baïz9, Ulrike Gehring10, Soesma A. Jankipersadsing1,2, Pieter van der Vlies2, Cleo C. van Diemen2, Bianca van Rijkom2, Jocelyne Just9,11, Inger Kull12, Juha Kere3,13, Josep Maria Antó5,7,8,14, Jean Bousquet15,16,17,18, Alexandra Zhernakova2, Cisca Wijmenga2, Isabella Annesi-Maesano9, Jordi Sunyer5,7,8,14, Erik Melén19, Yang Li2*, Dirkje S. -

Ciliary Dyneins and Dynein Related Ciliopathies

cells Review Ciliary Dyneins and Dynein Related Ciliopathies Dinu Antony 1,2,3, Han G. Brunner 2,3 and Miriam Schmidts 1,2,3,* 1 Center for Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, University Hospital Freiburg, Freiburg University Faculty of Medicine, Mathildenstrasse 1, 79106 Freiburg, Germany; [email protected] 2 Genome Research Division, Human Genetics Department, Radboud University Medical Center, Geert Grooteplein Zuid 10, 6525 KL Nijmegen, The Netherlands; [email protected] 3 Radboud Institute for Molecular Life Sciences (RIMLS), Geert Grooteplein Zuid 10, 6525 KL Nijmegen, The Netherlands * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-761-44391; Fax: +49-761-44710 Abstract: Although ubiquitously present, the relevance of cilia for vertebrate development and health has long been underrated. However, the aberration or dysfunction of ciliary structures or components results in a large heterogeneous group of disorders in mammals, termed ciliopathies. The majority of human ciliopathy cases are caused by malfunction of the ciliary dynein motor activity, powering retrograde intraflagellar transport (enabled by the cytoplasmic dynein-2 complex) or axonemal movement (axonemal dynein complexes). Despite a partially shared evolutionary developmental path and shared ciliary localization, the cytoplasmic dynein-2 and axonemal dynein functions are markedly different: while cytoplasmic dynein-2 complex dysfunction results in an ultra-rare syndromal skeleto-renal phenotype with a high lethality, axonemal dynein dysfunction is associated with a motile cilia dysfunction disorder, primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) or Kartagener syndrome, causing recurrent airway infection, degenerative lung disease, laterality defects, and infertility. In this review, we provide an overview of ciliary dynein complex compositions, their functions, clinical disease hallmarks of ciliary dynein disorders, presumed underlying pathomechanisms, and novel Citation: Antony, D.; Brunner, H.G.; developments in the field. -

Characterization of Primary Cilia and Intraflagellar Transport 20 in the Epidermis

Characterization of Primary Cilia and Intraflagellar Transport 20 in the Epidermis Steven H. Su Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Steven H. Su All Rights Reserved Abstract Characterization of Primary Cilia and Intraflagellar Transport 20 in the Epidermis Steven H. Su Mammalian skin is a dynamic organ that constantly undergoes self-renewal during homeostasis and regenerates in response to injury. Crucial for the skin’s self-renewal and regenerative capabilities is the epidermis and its stem cell populations. Here we have interrogated the role of primary cilia and Intraflagellar Transport 20 (Ift20) in epidermal development as well as during homeostasis and wound healing in postnatal, adult skin. Using a transgenic mouse model with fluorescent markers for primary cilia and basal bodies, we characterized epidermal primary cilia during embryonic development as well as in postnatal and adult skin and find that both the Interfollicular Epidermis (IFE) and hair follicles (HFs) are highly ciliated throughout development as well as in postnatal and adult skin. Leveraging this transgenic mouse, we also developed a technique for live imaging of epidermal primary cilia in ex vivo mouse embryos and discovered that epidermal primary cilia undergo ectocytosis, a ciliary mechanism previously only observed in vitro. We also generated a mouse model for targeted ablation of Ift20 in the hair follicle stem cells (HF-SCs) of adult mice. We find that loss of Ift20 in HF-SCs inhibits ciliogenesis, as expected, but strikingly it also inhibits hair regrowth. -

Perkinelmer Genomics to Request the Saliva Swab Collection Kit for Patients That Cannot Provide a Blood Sample As Whole Blood Is the Preferred Sample

Eye Disorders Comprehensive Panel Test Code D4306 Test Summary This test analyzes 211 genes that have been associated with ocular disorders. Turn-Around-Time (TAT)* 3 - 5 weeks Acceptable Sample Types Whole Blood (EDTA) (Preferred sample type) DNA, Isolated Dried Blood Spots Saliva Acceptable Billing Types Self (patient) Payment Institutional Billing Commercial Insurance Indications for Testing Individuals with an eye disease suspected to be genetic in origin Individuals with a family history of eye disease Individuals suspected to have a syndrome associated with an eye disease Test Description This panel analyzes 211 genes that have been associated with ocular disorders. Both sequencing and deletion/duplication (CNV) analysis will be performed on the coding regions of all genes included (unless otherwise marked). All analysis is performed utilizing Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology. CNV analysis is designed to detect the majority of deletions and duplications of three exons or greater in size. Smaller CNV events may also be detected and reported, but additional follow-up testing is recommended if a smaller CNV is suspected. All variants are classified according to ACMG guidelines. Condition Description Diseases associated with this panel include microphtalmia, anophthalmia, coloboma, progressive external ophthalmoplegia, optic nerve atrophy, retinal dystrophies, retinitis pigementosa, macular degeneration, flecked-retinal disorders, Usher syndrome, albinsm, Aloprt syndrome, Bardet Biedl syndrome, pulmonary fibrosis, and Hermansky-Pudlak -

An EMT-Primary Cilium-GLIS2 Signaling Axis Regulates Mammogenesis and Claudin-Low Breast Tumorigenesis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.29.424695; this version posted December 29, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 An EMT-primary cilium-GLIS2 signaling axis regulates mammogenesis 2 and claudin-low breast tumorigenesis 3 4 5 6 7 Molly M. Wilson1, Céline Callens2, Matthieu Le Gallo3,4, Svetlana Mironov2, Qiong Ding5, 8 Amandine Salamagnon2, Tony E. Chavarria1, Abena D. Peasah6, Arjun Bhutkar1, Sophie 9 Martin3,4, Florence Godey3,4, Patrick Tas3,4, Anton M. Jetten8, Jane E. Visvader7, Robert A. 10 Weinberg9, Massimo Attanasio5, Claude Prigent2, Jacqueline A. Lees1, Vincent J Guen2* 11 12 13 14 1Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and Department of Biology, Massachusetts 15 Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. 16 2Institut de Génétique et Développement de Rennes - Centre National de la Recherche 17 Scientifique, Rennes, France. 18 3INSERM U1242, Rennes 1 University, Rennes, France. 19 4Centre de Lutte Contre le Cancer Eugène Marquis, Rennes, France. 20 5Department of Internal Medicine, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, IA, 21 USA. 22 6Department of Biological Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 23 USA. 24 7Stem Cells and Cancer Division, The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research and 25 Department of Medical Biology, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia. 26 8Cell Biology Section, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Environmental Health 27 Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA. 28 9MIT Department of Biology and the Whitehead Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA. -

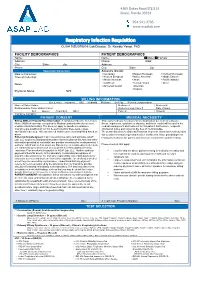

Lab Respiratory NGS Requisition Form

4305 Oakes Road STE 513 Davie, Florida 33314 954-541-3705 www.asaplab.com Respiratory Infection Requisition CLIA# 10D2079014: Lab Director: Dr. Kambiz Yaraei, PhD FACILITY DEMOGRAPHICS PATIENT DEMOGRAPHICS Name: Name: Male Female Address: Phone: DOB: City: State: Zip: Address: Phone: City: State: Zip: Specimen Collection Ancestry (Circle): Date of Collection: Caucasian Eastern European Northern European Time of Collection: Western European Native American Middle Eastern African American Asian Pacific Islander Notes: Caribbean Central / South Other ______ Ashkenazi Jewish American Hispanic Physician Name: NPI: BILLING INFORMATION Bill: (Circle) Insurance HAS Medicaid Medicare Self Pay Workers Compensation Name of Policy Holder: Medicare # Medicaid # Relationship to Policy Holder (Circle) Worker’s Comp Claim # Date of Injury Self Spouse Dependent Other: _____________ Policy # Group # Insurance Company: PATIENT CONSENT MEDICAL NECESSITY Billing ABN and Patient Plan Information: A completed Advance Beneficiary This test is medically necessary for the diagnosis or detection of a disease, Notice (ABN) of coverage is required for Medicare patients who do not meet illness, impairment, syndrome or disorder, and these results will be used in the medical criteria for testing. This does not apply to specific site analyses. medical management and treatment for this patient. Furthermore, recipients’ Insurance pre-qualification will not be performed for these tests, unless information is true and correct to the best of my knowledge. specifically requested. All tests ordered shall be processed and billed based on The person listed as the Ordering Physician or genetic counselor is authorized by payor. law to order the test(s) requested herein. I confirm that I have provided genetic Patient Acknowledgment: I am covered by insurance and authorize ASAP testing information to the patient and they have consented to genetic testing. -

Cilia and Polycystic Kidney Disease, Kith and Kin Liwei Huang* and Joshua H

Cilia and Polycystic Kidney Disease, Kith and Kin Liwei Huang* and Joshua H. Lipschutz In the past decade, cilia have been found to play important roles in renal summarizes the most recent advances in cilia and PKD research, with special cystogenesis. Many genes, such as PKD1 and PKD2 which, when mutated, emphasis on the mechanisms of cytoplasmic and intraciliary protein transport cause autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), have been during ciliogenesis. Birth Defects Research (Part C) 00:000–000, 2014. found to localize to primary cilia. The cilium functions as a sensor to transmit extracellular signals into the cell. Abnormal cilia structure and function are VC 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. associated with the development of polyscystic kidney disease (PKD). Cilia assembly includes centriole migration to the apical surface of the cell, ciliary Key words: polycystic kidney disease; cilia; planar cell polarity; exocyst vesicle docking and fusion with the cell membrane at the intended site of cilium outgrowth, and microtubule growth from the basal body. This review Introduction genetic disorder in humans (Grantham, 2001). Mutations Cilia are thin rod-like organelles found on the surface of in PKD1, the gene encoding polycystin-1, and PKD2, the human eukaryotic cells. First described by Anthony van gene encoding polycystin-2, have been identified as the Leeuwenhoek in 1675 (Dobell, 1932), they were originally cause of ADPKD (The International Polycystic Kidney Dis- defined by their motility, being structurally and functionally ease Consortium, 1995; Mochizuki et al., 1996). Autosomal similar to eukaryotic flagella. In 1876 and 1898 (Langer- recessive PKD (ARPKD), a severe form of PKD that hans, 1876; Zimmermann, 1898), another class of cilia was presents primarily in infancy and childhood, is caused by a described, the solitary (or nonmotile) cilia, which were mutation in the polycystic kidney and hepatic disease1 renamed primary cilia in 1968 (Sorokin, 1968). -

Supplementary Information – Postema Et Al., the Genetics of Situs Inversus Totalis Without Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

1 Supplementary information – Postema et al., The genetics of situs inversus totalis without primary ciliary dyskinesia Table of Contents: Supplementary Methods 2 Supplementary Results 5 Supplementary References 6 Supplementary Tables and Figures Table S1. Subject characteristics 9 Table S2. Inbreeding coefficients per subject 10 Figure S1. Multidimensional scaling to capture overall genomic diversity 11 among the 30 study samples Table S3. Significantly enriched gene-sets under a recessive mutation model 12 Table S4. Broader list of candidate genes, and the sources that led to their 13 inclusion Table S5. Potential recessive and X-linked mutations in the unsolved cases 15 Table S6. Potential mutations in the unsolved cases, dominant model 22 2 1.0 Supplementary Methods 1.1 Participants Fifteen people with radiologically documented SIT, including nine without PCD and six with Kartagener syndrome, and 15 healthy controls matched for age, sex, education and handedness, were recruited from Ghent University Hospital and Middelheim Hospital Antwerp. Details about the recruitment and selection procedure have been described elsewhere (1). Briefly, among the 15 people with radiologically documented SIT, those who had symptoms reminiscent of PCD, or who were formally diagnosed with PCD according to their medical record, were categorized as having Kartagener syndrome. Those who had no reported symptoms or formal diagnosis of PCD were assigned to the non-PCD SIT group. Handedness was assessed using the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI) (2). Tables 1 and S1 give overviews of the participants and their characteristics. Note that one non-PCD SIT subject reported being forced to switch from left- to right-handedness in childhood, in which case five out of nine of the non-PCD SIT cases are naturally left-handed (Table 1, Table S1). -

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Table 1. Panels (utilized in this study) and the genes included in each of them are summarized below. Nephrotic Syndrome (NS)/Focal ACTN4, ANKFY1, ANLN, APOL1, ARHGAP24, ARHGDIA, CD2AP, CDK20, COL4A3, COL4A4, COL4A5, COL4A6, COQ2, COQ6, COQ8B, CRB2, CUBN, Segmental DGKE, DLC1, EMP2, FAT1, GAPVD1, GON7, INF2, ITGA3, ITGB4, ITSN1, ITSN2, KANK1, KANK2, KANK4, KAT2B, KIRREL1, LAGE3, LAMA5, LAMB2, Glomerulosclerosis LMX1B, MAFB, MAGI2, MYH9, MYO1E, NEU1, NFKB2, NPHS1, NPHS2, NUP107, NUP133, NUP160, NUP205, NUP93, OSGEP, PAX2, PDSS2, PLCE1, (FSGS) Panel PTPRO, SCARB2, SGPL1, SMARCAL1, TBC1D8B, TNS2, TP53RK, TPRKB, TRIM8, TRPC6, TTC21B, WDR4, WDR73, WT1, XPO5, YRDC Alport syndrome COL4A3, COL4A4, COL4A5, COL4A6 Panel Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney DNAJB11, GANAB, HNF1B, PKD1, PKD2 Disease (ADPKD) panel Recessive Polycystic Kidney DZIP1L, PKHD1 Disease (ARPKD) panel Hereditary cystic ANKS6, CEP164, CEP290, CEP83, COL4A1, CRB2, DCDC2, DICER1, DNAJB11, DZIP1L, GANAB, GLIS2, HNF1B, IFT172, INVS, IQCB1, JAG1, LRP5, kidney disease MAPKBP1, MUC1, NEK8, NOTCH2, NPHP1, NPHP3, NPHP4, OFD1, PAX2, PKD1, PKD2, PKHD1, RPGRIP1L, SDCCAG8, SEC61A1, TMEM67, TSC1, panel TSC2, TTC21B, UMOD, VHL, WDR19, ZNF423 Nephrotic NPHS1, NPHS2, WT1, PLCE1, LAMB2 Syndrome Autosomal Dominant and Recessive Polycystic Kidney DNAJB11, DZIP1L, GANAB, HNF1B, PKD1, PKD2, PKHD1 Disease (ADPKD and ARPKD) Panel Distal Renal Tubular Acidosis ATP6V0A4, ATP6V1B1, CA2, SLC4A1 Panel Atypical Hemolytic Uremic syndrome C3, CFB, CFH, CFHR1, CFHR3, CFHR5, CFI, DGKE, MCP, THBD -

Cystic Kidney Diseases and During Vertebrate Gastrulation

Pediatr Nephrol (2011) 26:1181–1195 DOI 10.1007/s00467-010-1697-5 REVIEW Cystic diseases of the kidney: ciliary dysfunction and cystogenic mechanisms Cecilia Gascue & Nicholas Katsanis & Jose L. Badano Received: 3 August 2010 /Revised: 15 September 2010 /Accepted: 15 October 2010 /Published online: 27 November 2010 # IPNA 2010 Abstract Ciliary dysfunction has emerged as a common Introduction factor underlying the pathogenesis of both syndromic and isolated kidney cystic disease, an observation that has Cystic diseases of the kidney are a significant contributor to contributed to the unification of human genetic disorders of renal malformations and a common cause of end stage renal the cilium, the ciliopathies. Such grouping is underscored disease (ESRD). This classification encompasses a number by two major observations: the fact that genes encoding of human disorders that range from conditions in which ciliary proteins can contribute causal and modifying cyst formation is either the sole or the main clinical mutations across several clinically discrete ciliopathies, manifestation, to pleiotropic syndromes where cyst forma- and the emerging realization that an understanding of the tion is but one of the observed pathologies, exhibits clinical pathology of one ciliopathy can provide valuable variable penetrance, and can sometimes be undetectable insight into the pathomechanism of renal cyst formation until later in life or upon necropsy (Table 1;[1]). elsewhere in the ciliopathy spectrum. In this review, we Importantly, although the different cystic kidney disorders discuss and attempt to stratify the different lines of are clinically discrete entities, an extensive body of data proposed cilia-driven mechanisms for cystogenesis, ranging fueled by a combination of mutation identification in from mechano- and chemo-sensation, to cell shape and humans and studies in animal models suggests a common polarization, to the transduction of a variety of signaling thread, where virtually all known renal cystic disease- cascades. -

Ciliopathies

T h e new england journal o f medicine Review article Mechanisms of Disease Robert S. Schwartz, M.D., Editor Ciliopathies Friedhelm Hildebrandt, M.D., Thomas Benzing, M.D., and Nicholas Katsanis, Ph.D. iverse developmental and degenerative single-gene disor- From the Howard Hughes Medical Insti- ders such as polycystic kidney disease, nephronophthisis, retinitis pigmen- tute and the Departments of Pediatrics and Human Genetics, University of Michi- tosa, the Bardet–Biedl syndrome, the Joubert syndrome, and the Meckel gan Health System, Ann Arbor (F.H.); the D Renal Division, Department of Medicine, syndrome may be categorized as ciliopathies — a recent concept that describes dis- eases characterized by dysfunction of a hairlike cellular organelle called the cilium. Center for Molecular Medicine, and Co- logne Cluster of Excellence in Cellular Most of the proteins that are altered in these single-gene disorders function at the Stress Responses in Aging-Associated Dis- level of the cilium–centrosome complex, which represents nature’s universal system eases, University of Cologne, Cologne, for cellular detection and management of external signals. Cilia are microtubule- Germany (T.B.); and the Center for Hu- man Disease Modeling and the Depart- based structures found on almost all vertebrate cells. They originate from a basal ments of Pediatrics and Cell Biology, body, a modified centrosome, which is the organelle that forms the spindle poles Duke University Medical Center, Durham, during mitosis. The important role that the cilium–centrosome complex plays in NC (N.K.). Address reprint requests to Dr. Hildebrandt at Howard Hughes Med- the normal function of most tissues appears to account for the involvement of mul- ical Institute, Departments of Pediatrics tiple organ systems in ciliopathies. -

Renal Disease

SEQUENCING: Renal Disease Sample shipping address: Sample drop-off locations: Washington University - Department of Pathology & Immunology Children’s Hospital Institute of Health (IOH) Core Lab Clinical Support Services Office One Children’s Place 425 S. Euclid Ave. 425 South Euclid Avenue, Campus Box 8024, St. Louis, MO 63110 Central Receiving 2N-25 Room 4701 Tel: (314) 747-7337| Fax: (314) 747-7336 St. Louis, MO 63110 St. Louis, MO 63110 Email: [email protected] Tel: (314) 454-4161 Tel: (314) 362-1470 This requisition has two pages, please complete both pages to ensure testing PHYSICIAN ORDERING TEST (Required - NPI) PATIENT IDENTIFICATION Name: Patient Status Inpatient Outpatient Office visit Institution: Name Last: First MI: NPI: Email: DOB (mm/dd/yyyy): Gender: Male Female Address: Medical Record # (if applicable): City: State: Zip: Address: Phone: Fax: City: State: Zip: Alternative Contact Name: Ethnicity (select all that apply) Phone: Email: African American Asian Caucasian/NW European NOTES: E Indian Hispanic Jewish-Ashkenazi Jewish-Sephardic Mediterranean Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander Other: SPECIMEN TYPE Date Collected (mm/dd/yyyy): Time: Directions Collected By: 1. Draw 3-5 ml of peripheral blood in lavender top EDTA tube 2. Label tube with patient first/last name, DOB, and collection date/time Sample Type (Select one) 3. Place tube in a biohazard bag and form into document sleeve of the biohazard bag, Peripheral Blood ensuring no patient information is visible 4. Ship specimen overnight in appropriate packaging at room temperature