Lucas Critique After the Crisis: a Historicization and Review of One Theory’S Eminence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three US Economists Win Nobel for Work on Asset Prices 14 October 2013, by Karl Ritter

Three US economists win Nobel for work on asset prices 14 October 2013, by Karl Ritter information that investors can't outperform markets in the short term. This was a breakthrough that helped popularize index funds, which invest in broad market categories instead of trying to pick individual winners. Two decades later, Shiller reached a separate conclusion: That over the long run, markets can often be irrational, subject to booms and busts and the whims of human behavior. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences noted that the two men's findings "might seem both surprising and contradictory." Hansen developed a statistical method to test theories of asset pricing. In this Monday, June 15, 2009, file photo, Rober Shiller, a professor of economics at Yale, participates in a panel discussion at Time Warner's headquarters in New York. The three economists shared the $1.2 million prize, Americans Shiller, Eugene Fama and Lars Peter Hansen the last of this year's Nobel awards to be have won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic announced. Sciences, Monday, Oct. 14, 2013. (AP Photo/Mark Lennihan, File) "Their methods have shaped subsequent research in the field and their findings have been highly influential both academically and practically," the academy said. Three American professors won the Nobel prize for economics Monday for shedding light on how Monday morning, Hansen said he received a phone stock, bond and house prices move over time— call from Sweden while on his way to the gym. He work that's changed how people around the world said he wasn't sure how he'll celebrate but said he invest. -

M31193119 - BBRUNIRUNI TTEXT.Inddext.Indd 2200 227/02/20137/02/2013 08:1708:17 Altruistic Reciprocity 21

2. Altruistic reciprocity Herbert Gintis OTHER- REGARDING PREFERENCES AND STRONG RECIPROCITY By a self- regarding actor we mean an individual who maximizes his own payoff in social interactions. A self- regarding actor thus cares about the behavior of and payoffs to the other individuals only insofar as these impact his own payoff. The term ‘self- regarding’ is more accurate than ‘self- interested’ because an other-regarding individual is still acting to maximize utility and so can be described as self- interested. For instance, if I get great pleasure from your consumption, my gift to you may be self- interested, even though it is surely other- regarding. We can avoid confusion (and much pseudo- philosophical dis- cussion) by employing the self-regarding/other- regarding terminology. One major result of behavioral game theory is that when modeling market processes with well- specified contracts, such as double auctions (supply and demand) and oligopoly, game- theoretic predictions assuming self- regarding actors are accurate under a wide variety of social settings (see Kachelmaier and Shehata, 1992; Davis and Holt, 1993). The fact that self- regarding behavior explains market dynamics lends credence to the practice in neoclassical economics of assuming that individuals are self- regarding. However, it by no means justifies ‘Homo economicus’ because many economic transac- tions do not involve anonymous exchange. This includes employer- employee, creditor- debtor, and firm- client relationships. Nor does this result apply to the welfare implications of economic outcomes (e.g., people may care about the overall degree of economic inequality and/or their positions in the income and wealth distribution), to modeling the behavior of taxpayers (e.g., they may be more or less honest than a self- regarding indi- vidual, and they may prefer to transfer resources toward or away from other individu- als even at an expense to themselves) or to important aspects of economic policy (e.g., dealing with corruption, fraud, and other breaches of fiduciary responsibility). -

The Lucas Critique – Is It Really Relevant?

Working Paper Series Department of Business & Management Macroeconomic Methodology, Theory and Economic Policy (MaMTEP) No. 7, 2016 The Lucas Critique – is it really relevant? By Finn Olesen 1 Abstract: As one of the founding fathers of what became the modern macroeconomic mainstream, Robert E. Lucas has made several important contributions. In the present paper, the focus is especially on his famous ‘Lucas critique’, which had tremendous influence on how to build macroeconomic models and how to evaluate economic policies within the modern macroeconomic mainstream tradition. However, much of this critique should not come as a total surprise to Post Keynesians as Keynes himself actually discussed many of the elements present in Lucas’s 1976 article. JEL classification: B22, B31 & E20 Key words: Lucas, microfoundations for macroeconomics, realism & Post Keynesianism I have benefitted from useful comments from Robert Ayreton Bailey Smith and Peter Skott. 2 Introduction In 1976, Robert Lucas published a contribution that since has had an enormous impact on modern macroeconomics. Based on the Lucas critique, the search for an explicit microfoundation for macroeconomic theory began in earnest. Later on, consensus regarding methodological matters between the New Classical and the New Keynesian macroeconomists emerged. That is, it was accepted that macroeconomics could only be done within an equilibrium framework with intertemporal optimising households and firms using rational expectations. As such, the representative agent was born. Accepting such a framework has of course not only theoretical consequences but also methodological ones as for instance pointed out by McCombie & Pike (2013). Not only should macroeconomics rest upon explicit and antiquated, although accepted, microeconomic axioms; macroeconomic theory also had to be formulated exclusively by use of mathematical modelling1. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Archival Insights into the Evolution of Economics (and Related Projects) Berlet, C. (2017). Hayek, Mises, and the Iron Rule of Unintended Consequences. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part IX: Te Divine Right of the ‘Free’ Market. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Farrant, A., & McPhail, E. (2017). Hayek, Tatcher, and the Muddle of the Middle. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek: A Collaborative Biography Part IX the Divine Right of the Market. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Filip, B. (2018a). Hayek on Limited Democracy, Dictatorships and the ‘Free’ Market: An Interview in Argentina, 1977. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIII: ‘Fascism’ and Liberalism in the (Austrian) Classical Tradition. Basingstoke, England: Palgrave Macmillan. Filip, B. (2018b). Hayek and Popper on Piecemeal Engineering and Ordo- Liberalism. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIV: Orwell, Popper, Humboldt and Polanyi. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Friedman, M. F. (2017 [1991]). Say ‘No’ to Intolerance. In R. Leeson & C. Palm (Eds.), Milton Friedman on Freedom. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. © Te Editor(s) (if applicable) and Te Author(s) 2019 609 R. Leeson, Hayek: A Collaborative Biography, Archival Insights into the Evolution of Economics, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78069-6 610 Bibliography Glasner, D. (2018). Hayek, Gold, Defation and Nihilism. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek a Collaborative Biography Part XIII: ‘Fascism’ and Liberalism in the (Austrian) Classical Tradition. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Goldschmidt, N., & Hesse, J.-O. (2013). Eucken, Hayek, and the Road to Serfdom. In R. Leeson (Ed.), Hayek: A Collaborative Biography Part I Infuences, from Mises to Bartley. -

Handicapping Economics’ ‘Baby Nobel,’ the Clark Medal - Real Time E

Handicapping Economics’ ‘Baby Nobel,’ the Clark Medal - Real Time E... http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2010/04/22/handicapping-economics-ba... More News, Quotes, Companies, Videos SEARCH Thursday, April 22, 2010 As of 4:16 PM EDT BLOGS U.S. Edition Today's Paper Video Blogs Journal Community Log In Home World U.S. Business Markets Tech Personal Finance Life & Style Opinion Careers Real Estate Small Business WSJ BLOGS Reserve Bank of India’s ‘Nirvana’ Rate Economic insight and analysis from The Wall Street Journal. APRIL 22, 2010, 4:04 PM ET Handicapping Economics’ ‘Baby Nobel,’ the Clark Medal Article Comments (1) REAL TIME ECONOMICS HOME PAGE » 1 of 3 4/22/2010 4:20 PM Handicapping Economics’ ‘Baby Nobel,’ the Clark Medal - Real Time E... http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2010/04/22/handicapping-economics-ba... Email Printer Friendly Permalink Share: facebook Text Size By Justin Lahart Friday, the American Economic Association will present the John Bates Clark medal, awarded to the nation’s most promising economist under the age of 40. The Clark is known as the “Baby Nobel,” and with good reason. Of the 30 economists who have won it, 12 have gone on to win the Nobel, including Paul Samuelson and Milton Friedman. The award was given biennially until last year, when the AEA decided to give it annually. Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Esther Duflo, 37, is considered a frontrunner. The head of MIT’s Jameel Poverty Action Lab with Abhijit Banerjee, she’s been at the forefront of using randomized experiments to analyze development American Economic Association Most Popular programs. -

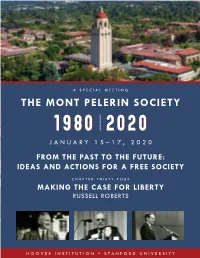

The Mont Pelerin Society

A SPECIAL MEETING THE MONT PELERIN SOCIETY JANUARY 15–17, 2020 FROM THE PAST TO THE FUTURE: IDEAS AND ACTIONS FOR A FREE SOCIETY CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR MAKING THE CASE FOR LIBERTY RUSSELL ROBERTS HOOVER INSTITUTION • STANFORD UNIVERSITY 1 1 MAKING THE CASE FOR LIBERTY Prepared for the January 2020 Mont Pelerin Society Meeting Hoover Institution, Stanford University Russ Roberts John and Jean De Nault Research Fellow Hoover Institution Stanford University [email protected] 1 2 According to many economists and pundits, we are living under the dominion of Milton Friedman’s free market, neoliberal worldview. Such is the claim of the recent book, The Economists’ Hour by Binyamin Applebaum. He blames the policy prescriptions of free- market economists for slower growth, inequality, and declining life expectancy. The most important figure in this seemingly disastrous intellectual revolution? “Milton Friedman, an elfin libertarian…Friedman offered an appealingly simple answer for the nation’s problems: Government should get out of the way.” A similar judgment is delivered in a recent article in the Boston Review by Suresh Naidu, Dani Rodrik, and Gabriel Zucman: Leading economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman were among the founders of the Mont Pelerin Society, the influential group of intellectuals whose advocacy of markets and hostility to government intervention proved highly effective in reshaping the policy landscape after 1980. Deregulation, financialization, dismantling of the welfare state, deinstitutionalization of labor markets, reduction in corporate and progressive taxation, and the pursuit of hyper-globalization—the culprits behind rising inequalities—all seem to be rooted in conventional economic doctrines. -

After the Phillips Curve: Persistence of High Inflation and High Unemployment

Conference Series No. 19 BAILY BOSWORTH FAIR FRIEDMAN HELLIWELL KLEIN LUCAS-SARGENT MC NEES MODIGLIANI MOORE MORRIS POOLE SOLOW WACHTER-WACHTER % FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON AFTER THE PHILLIPS CURVE: PERSISTENCE OF HIGH INFLATION AND HIGH UNEMPLOYMENT Proceedings of a Conference Held at Edgartown, Massachusetts June 1978 Sponsored by THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON THE FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF BOSTON CONFERENCE SERIES NO. 1 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES JUNE, 1969 NO. 2 THE INTERNATIONAL ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM OCTOBER, 1969 NO. 3 FINANCING STATE and LOCAL GOVERNMENTS in the SEVENTIES JUNE, 1970 NO. 4 HOUSING and MONETARY POLICY OCTOBER, 1970 NO. 5 CONSUMER SPENDING and MONETARY POLICY: THE LINKAGES JUNE, 1971 NO. 6 CANADIAN-UNITED STATES FINANCIAL RELATIONSHIPS SEPTEMBER, 1971 NO. 7 FINANCING PUBLIC SCHOOLS JANUARY, 1972 NO. 8 POLICIES for a MORE COMPETITIVE FINANCIAL SYSTEM JUNE, 1972 NO. 9 CONTROLLING MONETARY AGGREGATES II: the IMPLEMENTATION SEPTEMBER, 1972 NO. 10 ISSUES .in FEDERAL DEBT MANAGEMENT JUNE 1973 NO. 11 CREDIT ALLOCATION TECHNIQUES and MONETARY POLICY SEPBEMBER 1973 NO. 12 INTERNATIONAL ASPECTS of STABILIZATION POLICIES JUNE 1974 NO. 13 THE ECONOMICS of a NATIONAL ELECTRONIC FUNDS TRANSFER SYSTEM OCTOBER 1974 NO. 14 NEW MORTGAGE DESIGNS for an INFLATIONARY ENVIRONMENT JANUARY 1975 NO. 15 NEW ENGLAND and the ENERGY CRISIS OCTOBER 1975 NO. 16 FUNDING PENSIONS: ISSUES and IMPLICATIONS for FINANCIAL MARKETS OCTOBER 1976 NO. 17 MINORITY BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT NOVEMBER, 1976 NO. 18 KEY ISSUES in INTERNATIONAL BANKING OCTOBER, 1977 CONTENTS Opening Remarks FRANK E. MORRIS 7 I. Documenting the Problem 9 Diagnosing the Problem of Inflation and Unemployment in the Western World GEOFFREY H. -

Annual Proceedings of the Wealth and Well-Being of Nations

The Wealth and Well-Being of Nations of Nations Well-Being and Wealth The • Deirdre McCloskey Deirdre Contributors The Annual Proceedings of Deirdre Nansen McCloskey Joel Mokyr Jan Osborn Bart J. Wilson IX Volume 2016-2017 • Gus P. Gradinger Stephen T. Ziliak Emily Chamlee-Wright The Wealth and Well-Being of Nations Joshua C. Hall Seung (Ginny) Choi Virgil Henry Storr Bob Elder 2016-2017 Laura E. Grube Chuck Lewis Catherine M. Orr Department of Economics Volume IX: Bourgeois Virtues and the Great Enrichment: The Ideas and Influence of Deirdre Nansen McCloskey Warren Bruce Palmer, Editor The Miller Upton Program at Beloit College he Wealth and Well-Being of Nations was Testablished to honor Miller Upton, Beloit College’s sixth president. This annual forum provides our students and the wider community the opportunity to engage with some of the leading intellectual figures of our time. The forum is complemented by a suite of programs that enhance student and faculty engagement in the ideas and institutions that lay at the foundation of free and prosperous societies. Senior Seminar on The Wealth and Well-Being of Nations: ach year, seniors in the department of economics participate in a semester- Elong course that is built around the ideas and influence of that year’s Upton Scholar. By the time the Upton Scholar arrives in October, students will have read several of his or her books and research by other scholars that has been influenced by these writings. This advanced preparation provides students the rare opportunity to engage with a leading intellectual figure on a substantive and scholarly level. -

5. the Lucas Critique and Monetary Policy

5. The Lucas Critique and Monetary Policy John B. Taylor, May 6, 2013 Econometric Policy Evaluation: A Critique • Highly influential (Nobel Prize) • Adds to the case for policy rules • Shows difficulties of econometric policy evaluation when forward-looking expectations are introduced • But it left an impression of a “mission impossible” for monetary economists – Tended to draw researchers away from monetary policy research to real business cycle models • Nevertheless it was constructive – An alternative approach suggested through three examples: • One focussed on monetary policy – inflation-unemployment tradeoff • The other two focused on fiscal policy – consumption and investment • Worth studying in the original First Derive the Inflation-Output Tradeoff Derive "aggregate supply" function : Supply yit in market i at time t is given by P c yit yit yit where P yit is "permanent" or "normal" supply c yit is "cyclical" supply Supply curve in market i c e yit ( pit pit ) pit is the log of the actual price in market i at time t e pit is the perceived (in market i) general price level in the economy at time t Find conditional expectation of general price level pit pt zit 2 pt is distributed normally with mean ptand variance 2 zit is distributed normally with mean 0 and variance Thus 2 2 pt p is distributed N t p 2 2 2 it pt e 2 2 2 pit E( pt pit , I t1 ) pt [ /( )]( pit pt ) (1 ) pit pt where 2 /( 2 2 ) Covariance divided by the variance Now, substitute the conditional expectation e pit (1 ) pit -

![Myron S. Scholes [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5900/myron-s-scholes-ideological-profiles-of-the-economics-laureates-daniel-b-395900.webp)

Myron S. Scholes [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B

Myron S. Scholes [Ideological Profiles of the Economics Laureates] Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead Econ Journal Watch 10(3), September 2013: 590-593 Abstract Myron S. Scholes is among the 71 individuals who were awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel between 1969 and 2012. This ideological profile is part of the project called “The Ideological Migration of the Economics Laureates,” which fills the September 2013 issue of Econ Journal Watch. Keywords Classical liberalism, economists, Nobel Prize in economics, ideology, ideological migration, intellectual biography. JEL classification A11, A13, B2, B3 Link to this document http://econjwatch.org/file_download/766/ScholesIPEL.pdf ECON JOURNAL WATCH Schelling, Thomas C. 2007. Strategies of Commitment and Other Essays. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Schelling, Thomas C. 2013. Email correspondence with Daniel Klein, June 12. Schelling, Thomas C., and Morton H. Halperin. 1961. Strategy and Arms Control. New York: The Twentieth Century Fund. Myron S. Scholes by Daniel B. Klein, Ryan Daza, and Hannah Mead Myron Scholes (1941–) was born and raised in Ontario. His father, born in New York City, was a teacher in Rochester. He moved to Ontario to practice dentistry in 1930. Scholes’s mother moved as a young girl to Ontario from Russia and its pogroms (Scholes 2009a, 235). His mother and his uncle ran a successful chain of department stores. Scholes’s “first exposure to agency and contracting problems” was a family dispute that left his mother out of much of the business (Scholes 2009a, 235). In high school, he “enjoyed puzzles and financial issues,” succeeded in mathematics, physics, and biology, and subsequently was solicited to enter a engineering program by McMaster University (Scholes 2009a, 236-237). -

The Econometrics of the Lucas Critique: Estimation and Testing of Euler Equation Models with Time-Varying Reduced-Form Coefficients

The Econometrics of the Lucas Critique: Estimation and Testing of Euler Equation Models with Time-varying Reduced-form Coefficients Hong Li ∗y Princeton University Abstract The Lucas (1976) critique argued that the parameters of the traditional unrestricted macroeconometric models were unlikely to remain invariant in a changing economic envi- ronment. Since then, rational expectations models have become a fixture in macroeconomics Euler equations in particular. An important, though little acknowledged, implication of − the Lucas critique is that testing stability across regimes should be a natural diagnostic for the reliability of Euler equations. This paper formalizes this assertion econometrically in the framework of the classical two-step minimum distance method: The time-varying reduced- form in the first step reflects private agents' adaptation of their forecasts and behavior to the changing environment; The presumed ability of Euler conditions to deliver stable parame- ters that index tastes and technology is interpreted as a time-invariant second-step model. Within this framework, I am able to show, complementary to and independent of one an- other, both standard specification tests and stability tests are required for the evaluation of Euler equations. Moreover, this conclusion is shown to extend to other major estimation methods. Following this result, three standard investment Euler equations are submitted to examination. The empirical results tend to suggest that the standard models have not, thus far, been a success, at least for aggregate investment. JEL Classification: C13; C52; E22. Keywords: Parameter instability; Model validation testing; Classical minimum dis- tance estimation; The Lucas critique; Euler equations; Aggregate investment. ∗Department of Economics, Princeton University, NJ 08544. -

The Past, Present, and Future of Economics: a Celebration of the 125-Year Anniversary of the JPE and of Chicago Economics

The Past, Present, and Future of Economics: A Celebration of the 125-Year Anniversary of the JPE and of Chicago Economics Introduction John List Chairperson, Department of Economics Harald Uhlig Head Editor, Journal of Political Economy The Journal of Political Economy is celebrating its 125th anniversary this year. For that occasion, we decided to do something special for the JPE and for Chicago economics. We invited our senior colleagues at the de- partment and several at Booth to contribute to this collection of essays. We asked them to contribute around 5 pages of final printed pages plus ref- erences, providing their own and possibly unique perspective on the var- ious fields that we cover. There was not much in terms of instructions. On purpose, this special section is intended as a kaleidoscope, as a colorful assembly of views and perspectives, with the authors each bringing their own perspective and personality to bear. Each was given a topic according to his or her spe- cialty as a starting point, though quite a few chose to deviate from that, and that was welcome. Some chose to collaborate, whereas others did not. While not intended to be as encompassing as, say, a handbook chapter, we asked our colleagues that it would be good to point to a few key papers published in the JPE as a way of celebrating the influence of this journal in their field. It was suggested that we assemble the 200 most-cited papers published in the JPE as a guide and divvy them up across the contribu- tors, and so we did (with all the appropriate caveats).