Social Research Evidence Review to Inform Natural Environment Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clear Spring Health HMO Plan Provider Directory

Clear Spring Health HMO Plan Provider Directory This directory is current as of December 1, 2019. This directory provides a list of Clear Spring Health’s current network providers. This directory is for the Virginia Service Area: Alleghany, Amelia, Appomattox, Augusta, Bath, Buena Vista City, Caroline, Charles City, Chesterfield, Clarke, Colonial Heights City, Covington City, Craig, Cumberland, Danville City, Dinwiddie, Emporia City, Essex, Franklin, Franklin City, Galax City, Giles, Gloucester, Goochland, Greene, Greensville, Halifax, Hanover, Harrisonburg City, Henrico, Highland, Hopewell City, Isle of Wight, King and Queen, King William, Lexington City, Lunenburg, Madison, Mathews, Mecklenburg, Montgomery, Nelson, New Kent, Nottoway, Petersburg City, Pittsylvania, Poquoson City, Powhatan, Prince George, Pulaski, Radford City, Rappahannock, Richmond, Richmond City, Roanoke, Roanoke City, Rockbridge, Rockingham, Salem City, Southampton, Staunton City, Surry, Sussex, Warren, and Waynesboro City county. To access Clear Spring Health’s online provider directory, you can visit www.clearspringhealthcare.com. For any questions about the information contained in this directory, please call our Member Service Department at 877-384-1241, we are open 8:00 am to 8:00 pm Monday – Friday from April 1 – September 30 and 8:00 am to 8:00 pm Monday – Sunday from October 1 – March 31. TTY users should call 711. Out-of-network/non-contracted providers are under no obligation to treat Clear Spring Health members, except in emergency situations. Please call our Member Service number or see your Evidence of Coverage for more information, including the cost-sharing that applies to out-of- network services. Our plan has people and free interpreter services available to answer questions from disabled and non-English speaking members. -

Unclaimed Capital Credits If Your Name Appears on This List, You May Be Eligible for a Refund

Unclaimed Capital Credits If your name appears on this list, you may be eligible for a refund. Complete a Capital Credits Request Form and return it to TCEC. 0'GRADY JAMES ABERNATHY RENETHA A ADAIR ANDY 2 C INVESTMENT ABETE LILLIE ADAIR CURTIS 2 GIRLS AND A COF FEE ABEYTA EUSEBIO ADAIR KATHLEEN SHOP ABEYTA SAM ADAIR LEANARD 21 DIESEL SERVICE ABLA RANDALL ADAIR SHAYLIN 4 RED CATTLE CO ABODE CONSTRUCTIO N ADAME FERNAND 5 C FARMS ABRAHA EDEN M ADAMS & FIELD 54 DINER ABRAHAM RAMPHIS ADAMS ALFRED 54 TOWING & RECOV ERY ABREM TERRY ADAMS ALVIN A & C FEED STORE ABSOLUTE ENDEAVORS INC ADAMS ALVIN L A & I SKYLINE ROO FING ACEVEDO ARNALDO ADAMS ASHLEY A & M CONSTRUCTIO N CO ACEVEDO DELFINA A ADAMS BAPTIST CHURCH A & S FARMS ACEVEDO LEONARD ADAMS CHARLES G A C CROSSLEY MOTE L ACKER EARL ADAMS DARREL A W H ON CO ACKER LLOYD ADAMS DAVID A WILD HAIR ACKER NELDA ADAMS DELBERT AARON KENNETH ACKERMAN AMIRAH ADAMS DIANE M ABADI TEAME ACKERS MELVIN D ADAMS DORIS ABARE JASMINE ACOSTA ARMANDO ADAMS DOYLE G ABARE KALYN ACOSTA CESAR ADAMS FERTILIZER ABAYNEH SOLOMON ACOSTA FERNANDO ADAMS GARY ABB RANDALL CORPO RATION ACOSTA GARCIA R ADAMS HALEY D ABBOTT CLYDE ACOSTA GILBERTO E ADAMS HEATHER ABBOTT CLYDE V ACOSTA JOE ADAMS JEROD ABBOTT FLOYD K ACOSTA JOSE A ADAMS JERRY ABBOTT MAUREAN ACOSTA MARIA ADAMS JILL M ABBOTT ROBERT ACOSTA VICTOR ADAMS JOHN ABBOTT SCOTTY ACTION REALTY ADAMS JOHNNY ACTON PAM ADAMS LINDA Current as of February 2021 Page 1 of 190 Unclaimed Capital Credits If your name appears on this list, you may be eligible for a refund. -

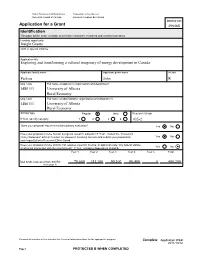

Application for a Grant 496468 Identification This Page Will Be Made Available to Selection Committee Members and External Assessors

Social Sciences and Humanities Conseil de recherches en Research Council of Canada sciences humaines du Canada Internal use Application for a Grant 496468 Identification This page will be made available to selection committee members and external assessors. Funding opportunity Insight Grants Joint or special initiative Application title Exploring and transforming a cultural imaginary of energy development in Canada Applicant family name Applicant given name Initials Parkins John R Org. code Full name of applicant's organization and department 1480111 University of Alberta Rural Economy Org. code Full name of administrative organization and department 1480111 University of Alberta Rural Economy Scholar type Regular New Research Group If New, specify category 1 2 3 4 435-2 Does your proposal require a multidisciplinary evaluation? Yes No Does your proposal involve human beings as research subjects? If "Yes", consult the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans and submit your proposal to Yes No your organization’s Research Ethics Board. Does your proposal involve activity that requires a permit, licence, or approval under any federal statute; Yes No or physical interaction with the environment? If 'Yes', complete Appendices A and B. Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Total Total funds requested from SSHRC 78,600 151,100 90,100 80,400 0 400,200 (from page 9) Personal information will be stored in the Personal Information Bank for the appropriate program. Complete Application WEB 2011/10/12 Page 1 PROTECTED B WHEN COMPLETED Social Sciences and Humanities Conseil de recherches en Research Council of Canada sciences humaines du Canada Family name, Given name Parkins, John Participants List names of your team members (co-applicants and collaborators) who will take part in the intellectual direction of the research. -

European Central Bank Executive Board 60640 Frankfurt Am Main Germany Brussels, 30 August 2017 Confirmatory Application to Th

The European Parliament Fabio De Masi - European Parliament - Rue Wiertz 60 - WIB 03M031 - 1047 Brussels European Central Bank Executive Board 60640 Frankfurt am Main Germany Brussels, 30 August 2017 Confirmatory application to the ECB reply dated 3 August 2017 Reference: LS/PT/2017/61 Dear Sir or Madam, We hereby submit a confirmatory application (Art. 7 (2) ECB/2004/3) based on your reply dated 3 August 2017, in which you fully refused access to the legal opinion “Responses to questions concerning the interpretation of Art. 14.4 of the Statute of the ESCB and of the ECB”. We submit the confirmatory application on the following grounds that the ECB has a legal obligation to disclose documents based on Article 2 (1) ECB/2004/3 in conjunction with Article 15 (3) TFEU. Presumption of the exceptions set out in Article 4 (2) ECB/2004/3 (undermining of the protection of court proceedings and legal advice) and Article 4 (3) ECB/2004/3 (undermining of the deliberation process) is unlawful. 1. Protection of legal advice, no undermining of legitimate interests – irrelevance of intentions, future deliberations and ‘erga omnes’ effects In your letter you state, “In the case at hand, public release of the legal opinion – which was sought by the ECB’s decision-making bodies and intended exclusively for their information and consideration – would undermine the ECB’s legitimate interest in receiving frank, objective and comprehensive legal advice. This especially so since this legal advice was not only essential for the decision-making bodies to feed -

Torrance City and Phone Directory

INSURANCE HOWARD G. LOCKE FIRE — AUTO 1405 Marcelina Tel. 135-M TORRANCE 1941-42 CITY DIRECTORY 49 Parker Robt E restr 24043 Hawthorne blvd, h24039 Peerless Laundry Agency Mrs Martha Evans agt Hawthorne blvd, Walteria 1322 Sartori—495 Parker Robt L (Esther N) crane opr h2019 220th Peery Harold supt KNX Transmitting Plant r Her- Parker Thos L (Wilma A) mtctr r!804 Arlington mosa Parkins John R eng r21902V2 Normandie Peet P Wm (Emma) foremn P E Ry hlOOS Portola Parkins Mildred A Mrs h21902% Normandie —379 Parks Apartments (F L Parks) 1420 ^ Marcelina av Pegors Harry H (Anna A) oil opr h!723 Martina—523 —60 Pendleton Wm C (Annie L) slsmn h4316 174th, R 1 Parks Fay L (Addie W) (Torrance Plumbing Co) Bx 218, Redondo hl418V2 Marcelina av—60 Penner Wm A Rev (Opal E) pastor Church of the Parr Cecil B (Ollie) belt tender h!725 Greenwood Nazarene h20507% N Royal blvd PAKRIY See also Perry PENNEY J C CO H R Lee mgr Department Store Parry Russell L (Vera May) eng Fire Dept hl820 1261-65 Sartori av—218 Gramercy av—467 Pennington Alfd L r2376 Maricopa pi—569W Parsons Everette G (Juanita) lab h!213 W Maple at Pennington Chas D (Ethel) mach P E Ry h2376 Parsons John L (Trula H) h!423 Acacia—1569 Maricopa pi—569W Parton Coy W (Carrie E) mech Col Steel h!502 218th Pennington Donald A (Cecil L) steelwkr h!407 Ama Pascoe Leroy W (Marie L) elec h832b Sartori pola Patchin Fannie M Mrs hl!56 W Milton Pepka Frank (Eliz) h2224 Sierra Patchin Lewis W (Marjorie R) mech Schultz & Peck- Perkin Henrietta Mrs h2208 Gramercy av—684J ham h2309 Andreo Perkin Thos H (Cicely) patrolmn City h!606 Ama Patrick Geo L (Alice) emp Shell Oil h24463 Ward, pola—372R (Walteria)—Redondo 7297 Perkins Bill (Hazel) smeltermn h!872 218th Patrick. -

Old Greshamian Magazine 2019

Old Greshamian Magazine 2019 Old Greshamian Old Greshamian Magazine November 2019 • Number 158 Old Greshamian Magazine November 2019 Number 158 Cover Photo: Olivia Colman with her Academy Award at the 2019 Oscars ceremony © PA Printed by The Lavenham Press 2 Contents Contact Details and OG Club Committee ........................................................................................ 4 GUY ALLEN Messages from the Chairman and the Headmaster ........................................................................ 5 Headmaster’s Speech Day Speech 2019 ....................................................................................... 8 The London Children’s Camp ........................................................................................................ 14 RECENT WORKS Reunions and Events in the Past Year .......................................................................................... 16 Friends of Gresham’s (FOGs) ....................................................................................................... 28 The Dyson Building ....................................................................................................................... 30 Development and The Gresham’s Foundation .............................................................................. 33 Gresham’s Futures ........................................................................................................................ 36 Honours and Distinctions.............................................................................................................. -

Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner Photographs, Negatives and Clippings--Portrait Files (N-Z) 7000.1C

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8w37tqm No online items Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (N-Z) 7000.1c Finding aid prepared by Rebecca Hirsch. Data entry done by Nikita Lamba, Siria Meza, Stephen Siegel, Brian Whitaker, Vivian Yan and Lindsey Zea The processing of this collection and the creation of this finding aid was funded by the generous support of the Council on Library and Information Resources. USC Libraries Special Collections Doheny Memorial Library 206 3550 Trousdale Parkway Los Angeles, California, 90089-0189 213-740-5900 [email protected] 2012 April 7000.1c 1 Title: Hearst Corporation Los Angeles Examiner photographs, negatives and clippings--portrait files (N-Z) Collection number: 7000.1c Contributing Institution: USC Libraries Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 833.75 linear ft.1997 boxes Date (bulk): Bulk, 1930-1959 Date (inclusive): 1903-1961 Abstract: This finding aid is for letters N-Z of portrait files of the Los Angeles Examiner photograph morgue. The finding aid for letters A-F is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1a . The finding aid for letters G-M is available at http://www.usc.edu/libraries/finding_aids/records/finding_aid.php?fa=7000.1b . creator: Hearst Corporation. Arrangement The photographic morgue of the Hearst newspaper the Los Angeles Examiner consists of the photographic print and negative files maintained by the newspaper from its inception in 1903 until its closing in 1962. It contains approximately 1.4 million prints and negatives. The collection is divided into multiple parts: 7000.1--Portrait files; 7000.2--Subject files; 7000.3--Oversize prints; 7000.4--Negatives. -

The Advocate - July 2, 1959 Catholic Church

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall The aC tholic Advocate Archives and Special Collections 7-2-1959 The Advocate - July 2, 1959 Catholic Church Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/catholic-advocate Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Catholic Church, "The Advocate - July 2, 1959" (1959). The Catholic Advocate. 101. https://scholarship.shu.edu/catholic-advocate/101 Aid Year, The Advocate Refugee Official Publication of Father the Archdioceae of Pleads Newark, N. J., and of the Diocese of Paterson, N. J. Holy VOL. 8, NO. 26 JULY 1959 THURSDAY, 2. PRICE: TEN VATICAN CITY In CENTS a mes ''hundreds of thousands of refu- of refugees” and exhort all Cath- and others likewise, might throw sage the World Refugee who opening gees . ire still held in olics to work make to a success open their frontier* «ver more has Year, Pope John XXIII railed camps or lodged in huts, humil- of the Refugee Year. generously, and speedily brin| or all Catholics to do whatever iated in their Protest Role as human dignity about the human and social re- they can to ease the sad and HF, ASKED plight heings, sometimes exposed Catholics to re- settlement of »o many unfortu- of in refugees. to the worst temptations of member that many cases the dis nate in people For Masons Speaking fluent French over couragement and despair." plight of the refugee is connected Radio with IN Vatican on June 28, the What man, he asked, hfs attachment to the GENEVA, meanwhile, WASHINGTON can re- The National voiced his main Church if Pontiff wholehearted indifferent to that ‘And anybody be where headquarters for the Council sight? of Catholic Men, through the support for Refugee Year pro- tempted—which Cod forbid—to campaign have been established, xecutive i secretary Martin H. -

2021 Seal of Biliteracy Recipients from Sacramento County

SEAL OF BILITERACY for Eligible Graduating High School Seniors 2021 Recognition Program Congratulations to Our 2021 Recipients! Welcome Welcome to the ninth annual Seal of Biliteracy recognition to honor multilingual students in Sacramento County! We would like to offer our congratulations to the high school seniors who have attained a high level of proficiency in English and another language. Each of these students has met rigorous state criteria and has demonstrated his or her linguistic abilities through examinations, grades, and coursework. By meeting these requirements, the California Department of Education awards each of David W. Gordon these students a gold “State Seal of Biliteracy” for his or her high school diploma. Sacramento County Superintendent of Schools In addition to English, this year’s Seal of Biliteracy recipients are proficient in 24 other languages, including American Sign Language, Arabic, Armenian, Cantonese, Dari, Farsi, French, German, Hindi, Hmong, Japanese, Korean, Latin, Mandarin, Pashto, Punjabi, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Turkish, Ukrainian, Urdu, and Vietnamese. More than 50 students have earned Seals in multiple languages. Sacramento County Office of Education is proud to offer language exams that support the diversity of the families and students in our schools. We would like to thank the following Sacramento County school districts, including independent charters, for their collaboration in this year’s Seal of Biliteracy program: Center Joint USD, Elk Grove USD, Folsom Cordova USD, Futures High School Charter, Galt Joint Union HSD, Natomas USD, Natomas Charter School, Natomas Pacific Pathways Prep Charter, River Delta USD, Sacramento City USD, San Juan USD, Twin Rivers USD, and Visions in Education Charter. -

Genomic Diversity in Naturally Transformable Streptococcus Pneumoniae

Genomic Diversity in Naturally Transformable Streptococcus pneumoniae Dr Donald James Inverarity BSc MBChB MRCP MSc DTMH DLSHTM FRCPath A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of PhD Division of Infection and Immunity Faculty of Biomedical and Life Sciences University of Glasgow February 2009 © Donald James Inverarity 2 Abstract Infections due to Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus) remain a substantial source of morbidity and mortality in both developing and developed countries despite a century of research and the development of effective therapeutic interventions (such as antibiotic therapy and vaccination). The ability of the pneumococcus to evade multiple classes of antibiotic through several genetically determined resistance mechanisms and its evasion of capsular polysaccharide based vaccines through serotype replacement and capsular switching, all reflect the extensive diversity and plasticity of the genome of this naturally transformable organism which can readily alter its genome in response to its environment and the pressures placed upon it in order to survive. The purpose of this thesis is to investigate this diversity from a genome sequence perspective and to relate these observations to pneumococcal molecular epidemiology in a region of high biodiversity, the pathogenesis of certain disease manifestations and assess for a possible bacterial genetic basis for the pneumococcal phenotypes of, “carriage” and, “invasion.” In order to do this, microarray comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) has been utilized to compare DNA from a variety of pneumococcal isolates chosen from 10 diverse serotypes and Multilocus Sequence Types and from clinically relevant serotypes and sequence types (particularly serotypes 3, 4 and 14 and sequence types ST9, ST246 and ST180)) against a reference, sequenced pneumococcal genome from an extensively investigated serotype 4 isolate – TIGR4. -

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

Interment Registry for Missoula City Cemetery

Interment Registry for Missoula City Cemetery Last Name First Name Age Date of Grave or Lot or Block Registry Death (N)=Niche (R)=Row or Wall # Pabst Vincent 69 12/28/1916 4 76 063 02289 Pace Oliver James 62 2/23/1956 5 21 59A 10833 Pacey George 62 9/30/1920 170 NP 009 02976 Padden Carl E 78 12/14/1971 7 19 57A 14542 Paddock Ada R 49 7/31/1960 6 14 60A 11944 Paddock Bertha Thorton Wirth 88 5/23/2003 3 11 14A 19381 Paddock Charles L 31 9/10/1938 6 9 18A 06496 Paddock Lewis Arthur 70 7/28/1947 4 9 18A 08575 Paddock Sarah Alice unk 6/3/1966 5 9 18A 13554 Paetke Jennie 42 3/25/1918 5 3 057 02505 Page Frank 69 8/24/1929 6 12 47A 04585 Page Paul 55 9/5/1964 8 9 30A 12940 Pahl Emily Zimbelman 77 2/27/1993 2 16 07B 18072 Pahl Roderick 81 9/2/2021 2 16 07B 20764 Pahlman Oscar 64 1/12/1929 8 22 45A 04454 Pak Alexander Xie Hong 14 8/13/2011 8 16 02A 20182 Palin Anna M unk 3/14/1899 1 2 016 Ledger Palin Isaie unk 9/3/1896 2 2 016 Ledger Palm Agnes Elizabeth 68 6/16/1966 3 19 027 13366 Palm Anna 51 8/16/1924 2 2 16A 03650 Palm Fredrick S 87 3/21/1957 1 19 027 11091 Palm No name SB 5/17/1920 1 36 55A 02936 Palmer Andrew 83 3/28/1950 5 13 57A 09272 Palmer Charles E 55 10/27/1981 3 19 18B 16415 Palmer Charles Sr 85 8/28/1978 4 19 18B 15885 Palmer Chloye Lewis 89 9/9/1982 6 6 18B 16539 Palmer Ed 32 3/31/1907 3 9 007 00696 Palmer Edna G 18 1/6/1910 8 1 031 01230 Palmer Ephesian SB 7/4/1994 3 36 41A 18279 Palmer Florence E 65 11/9/1922 8-1/2 128 063 03318 Palmer Frank 40 11/12/1908 4 12 063 01025 Palmer Frank B 71 12/4/1966 5 30 45A 13495 Palmer Frank E