Gestalt Breastfeeding: Helping Mothers and Infants Optimize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breastfeeding After Breast Surgery-V3-Formatted

Breastfeeding After Breast and Nipple Surgeries: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals By Diana West, BA, IBCLC, RLC PURPOSE A satisfying breastfeeding relationship is not precluded by insufficient milk production. When measures are taken to protect the milk supply that exists, minimize supplementation, The purpose of this guide is to provide the healthcare and increase milk production when possible, a mother with professional with an understanding of breast and nipple compromised milk production can have a satisfying surgeries and their effects upon lactation and the breastfeeding relationship with her baby. breastfeeding relationship. The effect of breast and nipple surgery upon lactation functionality and breastfeeding dynamics varies according to the type of surgery performed. This guide has delineated discussion of breastfeeding after PREDICTING LACTATION breast and nipple surgeries according to the three broad CAPABILITY AFTER BREAST AND categories: diagnostic, ablative, and therapeutic breast procedures, cosmetic breast surgeries, and nipple surgeries. NIPPLE SURGERIES The reasons, motivations, issues, concerns, stresses, and physical and psychological results share some The aspect of breast and nipple surgeries that is most likely to commonalities, but are largely unique to the type of surgery affect lactation is the surgical treatment of the areola and performed. For this reason, each type of surgery and its nipple. The location, orientation, and length of the incision effect upon lactation will be discussed independently. directly affect lactation capability by severing the parenchyma Methods to assess milk production and an overview of and innervation to the nipple/areolar complex. An incision feeding options to maximize milk production when near or on the areola, particularly in the lower, outer quadrant supplementation is necessary are presented. -

Anchor Buoy Drinks Menu

Anchor Buoy Drinks Menu COFFEE Cup 4 Mug 4.5 Grande 5 AMPLIFY KOMBUCHA 6 flat white | latte | cappuccino | long black | short Ginger lemon | Peach Mango |Raspberry Lime black | long macchiato | short macchiato | mocha | hot chocolate | baby chino BOTTLED JUICE add an extra shot of coffee 50c Orange 6 COFFEE EXTRAS 60c Apple 6 almond milk | soy milk | coconut milk | lactose free caramel syrup | vanilla syrup Apple Blackcurrant 6 ASK ABOUT A 1kg TAKE HOME BAG OF ELIXIR WATER COFFEE BEANS Lightly Sparkling 330ml 5.5 ANCHOR BUOY COLD DRINKS Lightly Sparkling 750ml 6.5 ICED COFFEE | ICED MOCHA 8-served with cream & ice cream Still Bottled Water 4.5 SOFT DRINK 4.5 FRAPPE |chocolate | vanilla | mocha |coffee 8-served with cream coke | diet coke | coke no sugar | fanta | lemonade| ginger beer | lemon lime & bitters ICED LATTE | ICED LONG BLACK 6 MILK SHAKE 7 chocolate| vanilla| strawberry| banana coffee | caramel ADD malt for 80c FRESHLY SQUEEZED JUICE 7.5 [mix your own] Apple | pineapple | orange | carrot | spinach | lemon | ginger |mint | watermelon | celery | cucumber SMOOTHIES 9 ACAI acai berries| banana |coconut water LOVE BERRY mixed berries | apple juice |banana PEANUT BUTTER CHOC almond milk | P.B | banana |choc SUPER GREEN mint | spinach| apple juice | banana| celery MUSCLE SMOOTHIE Banana | honey | whey protein | almond milk FROM THE BAR – Available from 10am ON TAP Stone & Wood Pacific Ale 4.4% 9 Great Northern Original 4.2% 8 Pinot Grigio Glass 12 | Bottle 50 SC Pannell SA- crisp Fat Yak 4.5% 8 and dry white that exhibit’s pear and lemon Lumber Yak Cider 4.5% (500m) 10 characteristics with fresh acidity Sauvignon Blanc Glass 9 | Bottle 40 FROM THE BOTTLE Golden Goose NZ- fresh aromas of tropical fruit such as Corona w/ lemon or lime 4.5% 8 pineapple and citrus overtones, with fresh acidity and a Lazy Yak Mid strength 3.5% 8 clean finish Stella 5.2% 8 Cascade Light 2.4% 7 Chardonnay Glass 9 | Bottle 40 Fox Creek SA- a fruity palate of golden peach, pineapple Corona Bucket [x4 bottles] 25 and apricot; subtle oak completing a full-bodied wine. -

PRODUCT CATALOGUE 2020 Australia’S #1 Foodservice Dairy Provider

PRODUCT CATALOGUE 2020 Australia’s #1 Foodservice Dairy provider. As Anchor™ Food Professionals, we understand what goes in to making a successful foodservice business. We’re dedicated to providing our customers with premium products and business expertise to help give them an edge in the highly competitive foodservice industry. WE WORK TO DELIVER VALUE TO OUR CUSTOMERS THROUGH: – Superior products – On-the-ground partnerships – Business solutions serving suggestion Delivering world-leading foodservice dairy products. We have over 20 years experience creating products specialised for the foodservice industry, and we’re always innovating. Driven by research and development based on insights from our chefs, bakers and specialist consultants, we have built our portfolio of products with unique attributes to drive functional performance for the foodservice industry. specialists in finding bakery performance serving suggestion deep expertise in /talian style cuisine trusted supplier to the world’s quick service restaurants A global reputation for trusted safety and quality. We are the high-performance foodservice business of Fonterra. Our products are manufactured (made) under Fonterra’s world-class food safety and quality systems. We share the natural goodness of dairy with food businesses across Australia and around the world. Proudly supporting the foodservice The Proud to be a Chef program recognises, develops and supports apprentice chefs to industry. become the culinary leaders of tomorrow. Investing in the industry at a grass roots Anchor™ Food Professionals are level, helps to insure we have a consistent proud to assist in the continuous flow of young talent into the industry. improvement and development of the culinary industry. -

Analysis of Hutterite Breastfeeding Patterns

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 Analysis of Hutterite breastfeeding patterns Christine Smith The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Christine, "Analysis of Hutterite breastfeeding patterns" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5556. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5556 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission \f No, I do not grant permission______ Author's Signature: . Date: .^Q|/q (/> Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. AN ANALYSIS OF HUTTERITE BREASTFEEDING PATTERNS by Christine Smith B.A. University of Montana, 1999 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana May 2006 Approved by rperson Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP41020 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Support Breastfeeding for a Healthier Planet

Support breastfeeding for a healthier planet REAS T B TF R EE O D P I P N U G S F O T R E A N LA HE P ALTHIER ONE FOR ALL, ALL FOR ONE World Breastfeeding Week 2020 (#WBW2020) highlights the links between breastfeeding and planetary health. We present a framework for understanding these links, outline some of the challenges and present some possible solutions. We need to acknowledge that ‘our house is on fire’ and that the next generation requires us to act quickly to reduce carbon footprints in every sphere of life... Breastfeeding is a part of this jigsaw, and urgent investment is needed across the sector. Joffe, Webster & Shenker. (2019) 1 OBJECTIVES OF #WBW2020 INFORM ANCHOR ENGAGE GALVANISE people about the links breastfeeding as with individuals action on improving the between breastfeeding and the a climate-smart and organisations health of the planet and environment/climate change decision for greater impact people through breastfeeding 1 Breastfeeding and planetary health The concept of planetary health has been defined as ‘the health of Sustainable development meets the needs of the current generation human civilisation and the state of the natural systems on which it without compromising future generations. Breastfeeding is key to all depends’2. The interconnected nature of people and the planet of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)3. requires that we find sustainable solutions that benefit both. Food and feeding matter Climate change and environmental degradation are some of the most footprint8 starting with how we feed our babies. Ongoing health urgent challenges facing our world today. -

Menu Options, We Are Not a Gluten Free Kitchen

Frank & Teressa’s APPETIZERS ® CAULIFLOWER WING BITES ANCHOR BAR DIP GF PIZZA LOGS A Buffalo Favorite ANCHOR Breaded cauliflower deep fried till golden Velvety blend of cream cheese, Anchor made In House! Egg roll wraps stuffed brown. Served plain or tossed in your Bar’s Original Bleu Cheese and our with mozzarella cheese and pepperoni. favorite Anchor Bar Wing Sauce. 8.99 Original (Medium) Anchor Bar Sauce Served with a side of pizza sauce. with chunks of chicken. Served warm BAR GARLIC BREAD 3pc for 7.99 or 5pc for 10.99 with multi colored tortilla chips 10.99 • BUFFALO ORIGINALS • Toasted, crispy roll topped with garlic, butter and mozzarella cheese baked to MOZZARELLA STIX (6pc) Breaded FRIED PICKLES (6pc) Large, juicy dill perfection. 5.99 and fried gooey mozzarella stix served pickle spears fried golden and served with ANCHOR BAR’S with a side of marinara. 8.99 a side of ranch. 7.99 WORLD FAMOUS WINGS ADD GRILLED CHICKEN + 4.99 All of our World Famous Wing orders are served ADD 5 WINGS SOUP & SALAD ADD MEATLESS WINGS + 4.99 to any order + 6.99 with traditional celery and bleu cheese, CHOICE OF DRESSINGS: Italian • Ranch • Caesar • Bleu Cheese ADD AVOCADO + 1.69 Thousand Island • Poppyseed • Honey Mustard • White Vinaigrette just like Mother served us that famous night in 1964. We want our loyal customers to know that we use only CAESAR SALAD Crisp romaine lettuce COBB SALAD Mixed greens topped BUFFALO CHICKEN SALAD unsaturated zero gram trans fat to fry our wings. with croutons and parmesan cheese, with crumbled bleu cheese, chopped Crispy or grilled chicken strips tossed tossed in a creamy caesar dressing. -

The Camel in Sumerian, the Bactrian Camel in Genesis?

Bible Lands e-Review 2014/S3 ‘Sweeter Than Camel’s Milk’: The Camel in Sumerian, The Bactrian Camel in Genesis? Wayne Horowitz, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and The Bible Lands Museum Jerusalem Introduction Much discussion in scholarly literature, and more recently of a popular nature on the internet, has focused on the issue of camel ownership by members of the Patriarchal family in the Book of Genesis. The context of this discussion is the chronological dating of the Genesis narrative where a number of passages depict the Patriarchs and Matriarchs of Israel as camel owners and riders. For example, Genesis 24:64 places Rebecca on camel back when she first catches sight of her husband to be Isaac, while in the next generation in Genesis 31:34, Rachel sits on a camel on her own journey to Canaan with her husband Jacob. The chronological implications of such passages for the dating of the Patriarchal Narratives are obvious. Such passages assure that the Patriarch Narratives in their current form cannot be earlier than the date of full camel domestication in the Ancient Near East, when camels came to be used as a means of transport. Consensus continues to place this date no earlier than the late second millennium BCE, the end of the Late Bronze Age, making this a terminus post quem for the Patriarchal Narratives themselves. However, there is some sporadic archaeological and art historical evidence which would allow for a Middle Bronze Age date for domestication of the camel, and so an earlier date for the historical background of the stories of the Patriarchs and Matriarchs of Israel.1 The short discussion below will suggest an alternative way of looking at this problem, based on textual evidence to be found in Sumerian. -

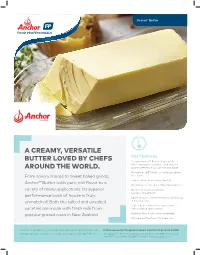

A Creamy, Versatile Butter Loved by Chefs Around The

Anchor™ Butter A CREAMY, VERSATILE Key features BUTTER LOVED BY CHEFS Creamy Anchor™ Butter starts with milk from grass-fed cows – and that’s a AROUND THE WORLD. quality difference you can see and taste. All-natural, rBST free*, no additives, gluten From savory sauces to sweet baked goods, free, halal. Higher smoke point when clarified. Anchor™ Butter adds pure, rich flavor to a No impurities, for easier clarification process. variety of menu applications. Its superior Greater yield when clarified (versus competitors). performance back of house is truly Lower lactose content means less browning unmatched! Both the salted and unsalted in baked goods. Higher butter fat content; performs varieties are made with fresh milk from well in baking applications. pasture-grazed cows in New Zealand. Optimal flavor, color and mouthfeel. Stronger butter flavor for table use. Contact your Anchor Food Professionals sales representative or Visit www.anchorfoodprofessionals.com for full product details. distributor representative to learn more about Anchor™ Butter. *No significant difference has been shown between rBST-treated and non-rBST treated milk. © 2014 Fonterra Foodservices (USA) Inc. Key benefits Consistent clarifying Wider margin of error when clarifying butter, for more consistent outcome. No skimming No skimming when clarified and no off flavors. Yields more Yields more clarified butter and less water and milk solids. Higher Butter Fat Higher butter fat percentage Anchor™ Butter Anchor™ Butter Product Name means excellent performance Unsalted Salted in baked goods. Pack Size 20/1 lbs 20/1 lbs Product Code 110586 110596 Improved dining experience UPC 852358001211 852358001204 Enjoyable flavor is appreciated by patrons, encouraging Case GTIN 10852358001218 10852358001201 repeat visits and improving Case Dimensions 9.84″ x 4.92″ x 13.9″ 9.84″ x 4.92″ x 13.9″ the overall dining experience. -

Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets

Product Bulletin Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets Melting Point 34°C 20 x 1kg Sheets – 20kg Carton PB.1377 l Version 02.0318 l UNRESTRICTED Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets from Fonterra are made from high quality fresh cream using word leading butter making technology. Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets consistently deliver the superior flavour and mouth-feel needed for pastry applications. Conveniently sized for commercial baking, Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets have the additional benefit of a standardised melting point. Product Characteristics Storage and Handling Manufactured from pasteurised milk or cream. Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets are a perishable food. Gives excellent baked through butter flavour to the In order to preserve their pure clean flavour they finished product. should be: Improved texture for superior lamination giving improved end product performance. Kept frozen at -10°C to -25°C in accordance with Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets are full of natural importing country regulations.. goodness – they contain no additives. Kept away from odours. Produced in a sophisticated processing plant to Kept out of direct sunlight. ensure product consistency. Used strictly in rotation. Sheeted form for convenience and cost savings. When stored frozen, Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets Suggested Uses have a maximum shelf-life of 24 months from the time of manufacture. Danish Pastries Shelf life under refrigerated conditions (2 - 4°C) is at Croissants least 8 weeks. Puff Pastry Unsalted Butter Bakery Sheets should be conditioned at 14 - 18°C before use. Packaging Typical Compositional Analysis A corrugated cardboard outer containing 20 wrapped 1kg butter sheets. Each sheet is wrapped individually in The analysis results listed in this product bulletin are high-density polyethylene. -

Composition of Camel Milk and Evaluation of Food Supply for Camels in Uzbekistan Valeriy V

Pak et al. Journal of Ethnic Foods (2019) 6:20 Journal of Ethnic Foods https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-019-0031-5 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Composition of camel milk and evaluation of food supply for camels in Uzbekistan Valeriy V. Pak1*, Olim K. Khojimatov2, Gulnara J. Abdiniyazova3 and Elena B. Magay4 Abstract Background: In Uzbekistan, local people consumed camel milk products since ancient time. Camel milk is a source of energy and nutrients which are consumed as raw or fermented products and also provides various potential health benefits for human. Methods: The data were collected during 2016–2018 by expeditions in desert and semi-desert regions of Uzbekistan. Three hundred sixty sheets of plants have been collected from those regions. Forty-two samples of raw camel milk were collected at two periods of the year: 21 samples during summer (June, July, and August) and 21 during winter (December, January, and February). Results and discussion: Analysis of the composition of camel milk samples revealed the particular richness of camel milk in protein and fat content. Average values of protein and fat were found as 4.04 ± 0.36% w/v and 4.89 ± 0.26% w/v, respectively. Analysis of the composition of camel milk showed that protein, fat, and dry matter contents were comparatively lower in the summer period. Also, it was found that the average values of all components decreased from December to February and had a tendency to grow from June to August. This finding suggests a seasonal variation in available food supply. Investigation of an available fodder flora revealed that a fodder base consists of around 300 plants. -

Selling After Description Pack Size Selling Discount

Selling After Description Pack Size Selling Discount AER AIR FRESHNER GEL COOL 9ML 9ML 695.00 590.75 AER A.FRESHNER REFIL PETA 9ML 9ML 495.00 420.75 NUTRINNOVATE AUSTR QUICK OATS 500GR 550.00 495.00 QUAKER INSTANT OATS RED 400GR 400GR 750.00 675.00 KELLOGGS CORN FLAKES 250GR 250GR 490.00 416.50 KELLOGGS CORN FLAKES 100GR 100GR 200.00 170.00 NUTRILINE CHOCOBLOBS 150GR 150GR 200.00 180.00 NESTLE MILO BALLS 170GR 170GR 325.00 276.25 SAMAPOSHA NUTRI PLUS KURAKKAN 200GR 80.00 68.00 YAHA POSHA 200GR 200GR 70.00 60.00 SAMAAYU GOTUKO: PORRIDGE 50GR 50GR 80.00 68.00 SAMAAYU HATHAW: PORRIDGE 50GR 50GR 80.00 68.00 SAMAAYU WELPEN: PORRIDGE 50GR 50GR 80.00 68.00 4GB CHOXY GRAIN BAR 20GR 20GR 20.00 17.00 NUTRILINE INSTANT OATS POUCH 500GR 275.00 233.75 SAMAPOSHA GRAINS & GREENS 200GR 100.00 85.00 TIARA CHOCOLA SWISS ROLL 200GR 200GR 200.00 180.00 TIARA VANILLA LAYER CAKE 320GR 320GR 250.00 225.00 PRIMA VANILLA SWISS ROLL 225GR 225GR 270.00 243.00 PRIMA STRAWBE.SWISS ROLL 225GR 225GR 270.00 243.00 TIPTOP DECK BRUSH 6INCH EACH 1EA 360.00 324.00 HSP-DUST PAN W/BRUSH 004 EACH 1EA 230.00 216.20 HSP-IRON HAND BRUSH EACH 1EA 200.00 188.00 HSP-ONLY TOILET BRUSH 007 EACH 1EA 145.00 136.30 HSP-ROU. COMODE BRSH W/CA EACH 1EA 220.00 206.80 HSP-FLOOR BRUSH BUTTERFLY EACH 1EA 385.00 361.90 TIPTOP FLAT BROOM EACH 1EA 412.00 370.80 HSP-PLAS.BROOM W/ST-HB001 EACH 1EA 295.00 277.30 TIPTOP COTTON MOP EACH 1EA 391.00 351.90 HSP-MOP HEAD WITH STICK EACH 1EA 455.00 427.70 HSP-FLOOR WIPER W/STK 1.2 EACH 1EA 315.00 296.10 HSP-MOP BUCKET PLAS. -

Label Redesign Creates a Powerful Brand Presence That Cannot Be Ignored Fonterra - Anchor ® Butter

CASE STUDY Label Redesign Creates a Powerful Brand Presence that Cannot be Ignored Fonterra - Anchor ® Butter Pressure-Sensitive Labels Restore Quality Image of Premium Butter Packaging What consumers see when they initially spot a product on shelf says a lot about the brand. If they’ve never heard of your product, first impressions are critical. Even if a consumer is already a customer, visual impact extends an initial greeting that confirms the brand promise and the consumer’s decision to look specifically for your product. But seeing a package with a loose or crinkled label could give the impression there wasn’t much care taken in handling, packaging or getting that product to the shelf. Because shelf impact plays such a critical role in the purchase decision, anything that undermines what the packaging needs to deliver is unacceptable. Making The Wrong Impression Fonterra is the world’s leading exporter of dairy products and is responsible for more than one- third of the international dairy trade. As with most products in the grocery environment, the company relies heavily on packaging to be the primary line of communication to its customers. Unfortunately an adhesion problem with the glue- applied paper labels on the lids for its Anchor® Spreadable Butter product was sending the wrong message to consumers in the Philippines, where the product holds prominent market share. The edges of the glue-applied labels often lifted up and got caught on other containers. As a result, the labels became easily creased and wrinkled. This negatively affected the overall shelf appeal and reflected poorly “We wanted to establish a new ‘look’ for the product to on the top-quality image Anchor holds throughout the country.