Karnataka Social Watch Report 2009-2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name of the State/UT KARNATAKA Period of Which Allocation of Foodgrain Is Sought ………………………………………………

ALLOCATION OF FOODGRAINS UNDER WELFARE INSTITUTIONS AND HOSTELS SCHEME (Note: The information must by posted on State Food Department Portal as well) Name of the State/UT KARNATAKA Period of Which allocation of foodgrain is sought ………………………………………………. Web link (to locate this information on the State Food Department Portal) ………………………………………………………….. No of Inmates Number of Year of Nature of Whether any UC pending Institutes Establishment Present Sl No District Taluk Name of the Institution Address Contact Details & E-mail ID Management (Govt. for past allocation? If so, (District of the Total Strength run/aided or Private) reasons thereof. wise) Institution Capacity (verified inmates) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 BAGALKOTE BAGALKOT 1 Superintendent of Government APMC Cross Navanagar Bagalkot Pin Boys Children s House Bagalkot 587103 [email protected], Contct - 1 9449908180 2001 36 36 Govt Aided NO BAGALKOTE BAGALKOT 2 SGV Institute Blind childrens SGV INSTITUTE BLIND CHILDRENS boarding school Vidyagiri Bagalkot BOARDING SCHOOL 8TH CROSS [email protected], Contct - CIDYAGIRI BAGALKOT 9964858524 2003 9 9 Govt Aided NO BAGALKOTE BAGALKOT 3 Superintendent Government Girls Behind Railway Station Near Pipe Home Bagalko Factory Badami road Bagalkot Pin 587101 [email protected], 9535226603 2011 34 34 Govt Aided NO BAGALKOTE JAMKHANDI 4 Sarvoday residential special school Maigur road Jamkhandi Pin 587301 for deaf and dumb children Jamakhandi [email protected], 9964951111 2008 65 65 Govt Aided NO BAGALKOTE HUNGUND 5 shri Yalagureshwar -

Karnataka State India Name Changes

INFORMATION PAPER Karnataka State, India: Name Changes Karnataka is a state in South West India. The official language of the state is Kannada1. Karnataka comprises 30 second-order administrative divisions, known as districts 2. The governor of Karnataka has issued a notification, which came into effect on 1st November 2014, officially changing the spellings of the names of 12 cities in the state to reflect the names in the local Kannada language. Several of these cities are the administrative seats of the districts of the same name. While the official notification refers to the cities, it appears that the district names are also changing3. These name changes are not yet reflected on all Indian government websites. The previous spellings are still used in the list of districts on the Official Website of the Government of Karnataka, but the new names are included on the National Informatics Centre (NIC) website4 and they can also be found on some district and city websites (see the table on the next page). It is likely to be some time before all names on signs are updated to reflect the changes5 and institutions such as Mysore University and Bangalore University are expected to retain their existing names6. PCGN policy for India is to use the Roman-script geographical names found on official sources7. The new names listed on the next page should be used for the populated places and the districts on all future UK government products or updates. In cases where the previous name is well-known or differs significantly from the new name, e.g. -

Census of India 2001 General Population Tables Karnataka

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 GENERAL POPULATION TABLES KARNATAKA (Table A-1 to A-4) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KARNATAKA Data Product Number 29-019-2001-Cen.Book (E) (ii) CONTENTS Page Preface v Acknowledgement Vll Figure at a Glance ]X Map relating to Administrative Divisions Xl SECTION -1 General Note 3 Census Concepts and Definitions 11-16 SECTION -2 Table A-I NUMBER OF VILLAGES, TOWNS, HOUSEHOLDS, POPULATION AND AREA Note 18 Diagram regarding Area and percentage to total Area State & District 2001 19 Map relating to Rural and Urban Population by Sex 2001 20 Map relating to Sex ratio 2001 21 Diagram regarding Area, India and States 2001 22 Diagram regarding Population, India and States 2001 23 Diagram regarding Population, State and Districts 2001 24 Map relating to Density of Population 25 Statements 27-68 Fly-Leaf 69 Table A-I (Part-I) 70- 82 Table A-I (Part-II) 83 - 98 Appendix A-I 99 -103 Annexure to Appendix A-I 104 Table A-2 : DECADAL VARIATION IN POPULATION SINCE 1901 Note 105 Statements 106 - 112 Fly-Leaf 113 Table A-2 114 - 120 Appendix A-2 121 - 122 Table A-3 : VILLAGES BY POPULATION SIZE CLASS Note 123 Statements 124 - 128 Fly-Leaf 129 Table A-3 130 - 149 Appendix A-3 150 - 154 (iii) Page Table A-4 TOWNS AND URBAN AGGLOMERATIONS CLASSIFIED BY POPULATION SIZE CLASS IN 2001 WITH VARIATION SINCE 1901 Note 155-156 Diagram regarding Growth of Urban Population showing percentage (1901-2001) 157- 158 Map showing Population of Towns in six size classes 2001 159 Map showing Urban Agglomerations 160 Statements 161-211 Alphabetical list of towns. -

Bangalore Urban District, Karnataka

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET BANGALORE URBAN DISTRICT, KARNATAKA SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE DECEMBER1 2008 FOREWORD Ground water contributes to about eighty percent of the drinking water requirements in the rural areas, fifty percent of the urban water requirements and more than fifty percent of the irrigation requirements of the nation. Central Ground Water Board has decided to bring out district level ground water information booklets highlighting the ground water scenario, its resource potential, quality aspects, recharge – discharge relationship, etc., for all the districts of the country. As part of this, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore, is preparing such booklets for all the 27 districts of Karnataka state, of which six of the districts fall under farmers’ distress category. The Bangalore urban district Ground Water Information Booklet has been prepared based on the information available and data collected from various state and central government organisations by several hydro-scientists of Central Ground Water Board with utmost care and dedication. This booklet has been prepared by Smt. Veena R Achutha , Assistant geophysicist, under the guidance of Dr. K.Md. Najeeb, Superintending Hydrogeologist, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore. The figures were prepared by S/Sri. H.P.Jayaprakash, Scientist-C and K.Rajarajan, Assistant Hydrogeologist. The efforts of Report processing section in finalising and bringing out the report in this format are commendable. I take this opportunity to congratulate them for the diligent and careful compilation and observation in the form of this booklet, which will certainly serve as a guiding document for further work and help the planners, administrators, hydrogeologists and engineers to plan the water resources management in a better way in the district. -

Bangalore Rural District, Karnataka

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD GROUND WATER INFORMATION BOOKLET BANGALORE RURAL DISTRICT, KARNATAKA SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE NOVEMBER 2008 FOREWORD Ground water contributes to about eighty percent of the drinking water requirements in the rural areas, fifty percent of the urban water requirements and more than fifty percent of the irrigation requirements of the nation. Central Ground Water Board has decided to bring out district level ground water information booklets highlighting the ground water scenario, its resource potential, quality aspects, recharge – discharge relationship, etc., for all the districts of the country. As part of this, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore, is preparing such booklets for all the 27 districts of Karnataka state, of which six of the districts fall under farmers’ distress category. The Bangalore Ruaral district Ground Water Information Booklet has been prepared based on the information available and data collected from various state and central government organisations by several hydro-scientists of Central Ground Water Board with utmost care and dedication. This booklet has been prepared by Shri A. Kannan, Scientist-B under the guidance of Dr. K. Md. Najeeb, Superintending Hydrogeologist, Central Ground Water Board, South Western Region, Bangalore. The figures were prepared by S/Sri. H.P.Jayaprakash, Scientist-C and K.Rajarajan, Assistant Hydrogeologist. The efforts of Report processing section in finalising and bringing out the report in this format are commendable. I take this opportunity to congratulate them for the diligent and careful compilation and observation in the form of this booklet, which will certainly serve as a guiding document for further work and help the planners, administrators, hydrogeologists and engineers to plan the water resources management in a better way in the district. -

Government AYUSHMAN BHARAT

AYUSHMAN BHARAT - AROGYA KARNATAKA EMPANELLED HOSPITALS LIST Govt/Priv Sl.no Hospital Name Address District Taluk Division Contact Mail id Scheme Speciality ate Government Community Health Centre Obstetrics and VijayapuraDevanahalli Ayushman gynaecology Community Health Centre Road Vijayapura Bangalore chcvijayapura@g 1 Bangalore Devanahalli govt 8027668505 Bharat - Arogya Dental Vijayapura Devanhalli division mail.com Karnataka Simple secondary general TalukBengaluru Rural- procedure 562135 Obstetrics and Ayushman Community Health Centre B M Road Kengeri Kote Bangalore girijagowdab@g gynaecology Paediatrics 2 Bangalore Bengaluru govt 8028483265 Bharat - Arogya Kengeri Bangalore 560060 division mail.com Simple secondary General Karnataka procedure Paediatric surgeries Community Health Centre Obstetrics and Ayushman Community Health Centre ThyamagondluNear Police Bangalore thyamagondluchc gynaecology 3 Bangalore Nelemangala govt 8027731202 Bharat - Arogya Thyamagondlu StationBangalore - Rural- division @gmail.com Dental Karnataka 562132 Simple secondary General procedure Paediatric Surgery Community Health Center Ayushman General Medicine Community Health Center Near Water Bangalore mophcavalhalli@ 4 Bangalore Bengaluru govt 8028473108 Bharat - Arogya Dental Avalahalli PlantationBangalore - division gmail.com Karnataka Obstetrics and Urban-560049 gynaecology Dental Obstetrics and Ayushman Tavarekere Hobli South Bangalore dr.candrappacercl gynaecology 5 CHC Chandrappa Cercle Bangalore Bengaluru govt 8028438330 Bharat - Arogya TalukBengaluru -

EGCGF) of SFAC, New Delhi During 8Th Quarter (January to March 2017) S

Proposed work plan for Publicity Awareness building camps of Central Sponsored Schemes (EGCGF) of SFAC, New Delhi during 8th Quarter (January to March 2017) S. Name of Category Block/Tehsil Number of SFAC FPO/FPC Name and Address of FPCs Tentative No. District of Camps FPO/FPC FPO/FPC (NABARD and dates for Departments/Non Organizing SFAC) camps Karnataka-9 (District-4 + Block-4 + State-1) 1 Bangalore State Level Urban/Rural – 21 15 6 Udigal Farmer Producer Company Limited 17-03-2017 15+6 58/3, 39/A, Cross, 11th Main, 4th 'T' Block, Jayanagar- 560041, Karnataka Anekal Horticulture Producer Company Limited 58/3, 39/A Cross, 11th Main, 4th 'T' block, Jayanagar- 560041, Karnataka Srigripura Horticulture Farmer Producer Company Limited #58/3, 39/A Cross, 11th Main, 4th 'T' Block, Jayanagar- 560041, Karnataka Gombenadu Horticulture Farmer Producer Company Limited # 58/3, 39/A Cross, 11th Main, 4th 'T' Block, Jayanagar- 560041, Karnataka Tubugere Horticulture Farmer Producer Company Limited # 58/3, 39/A, Cross, 11th Main, 4th 'T' Block, Jayanagar- 560041, Karnataka Varuna Horticulture Farmer Producer Company Limited# 58/3, 39/A Cross, 11th Main, 4th 'T' Block, Jayanagar, Bangalore, Karnataka, 560041 Sangama Horticulture Farmer Producer Company Limited #58/3, 39/A Cross, 11th Main, 4th 'T' Block, Jayanagar, Bangalore, Karnataka, 560041 Nanjanagud Horticulture Farmer Producer Company Limited #58/3, 39/A Cross, 11th Main, 4th 'T' Block, Jayanagar, Bangalore, Karnataka Malavalli Horticulture Farmer Producer Company Limited # 58/3, 39/A Cross, 11th -

In the High Court of Karnataka at Bengaluru

- 1 - IN THE HIGH COURT OF KARNATAKA AT BENGALURU DATED THIS THE 27 TH DAY OF APRIL 2015 PRESENT THE HON'BLE MR.D.H.WAGHELA, CHIEF JUSTICE AND THE HON'BLE MR.JUSTICE RAM MOHAN REDDY WA No.154/2007 c/w WA No.184/2007, WA No.95/2007, WA No.133/2007, WA No.134/2007, WA No.148/2007, WA No.152/2007, WA No.153/2007, WA No.155/2007, WA No.156/2007, WA No.251/2007 & 2701/2011, WA No.289/2007 & 2741-45/2011, WA No.250/2007, WA No.279/2007 & 2700/2011, WA No.638/2007, WA No.168/2007, WA Nos.174/2007 & 2683- 2697/2011, WA No.183/2007 and WA No.96/2007 (GM-MMS) IN WA No.154/2007 BETWEEN 1. STATE OF KARNATAKA REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY REVENUE DEPARTMENT M.S.BUILDING BANGALORE-560 001 2. THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER CHAMARAJANAGAR DISTRICT CHAMARAJANAGAR 3. THE DEPUTY DIRECTOR DEPARTMENT OF MINES AND GEOLOGY CHAMARAJANAGAR DISTRICT CHAMARAJANAGAR ... APPELLANTS (By Smt.NILOUFER AKBAR, AGA) - 2 - AND SRI GURUSIDDE GOWDA S/O SIDDEGOWDA AGED ABOUT 40 YEARS R/AT HARAVE HOBLI HARAVE VILLAGE CHAMARAJANAGAR TQ AND DISTRICT ... RESPONDENT THIS WRIT APPEAL IS FILED U/S 4 OF THE KARNATAKA HIGH COURT ACT PRAYING TO SET ASIDE THE ORDER PASSED IN WRIT PETITION No.5804/2006 DATED 21/04/2006. IN WA No.184./2007 BETWEEN 1. THE STATE OF KARNATAKA REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE M.S.BUILDINGS AMBEDKAR VEEDHI BANGALORE-560 001 2. THE DEPUTY COMMISSIONER CHAMARAJANAGAR DISTRICT CHAMARAJANAGAR 3. -

Detailed CV Name Prof. SOMANNA Educational Qualification

Detailed CV Name Prof. SOMANNA Educational Qualification : M.A, PhD, Diploma in folklore Designation : Professor Address for Correspondence : Prof. SOMANNA Professor in Kannada, S.V.P Kannada adhyayana samsthe Mangalore University, Mangalagangotri, Konaje Mangalore 574199 Karnataka E-mail : [email protected] Phone : 9886165134 Research Areas : Kannada Folklore Professional Teaching Experience: From 1.1.1996 to 02-12-2013 (18 years experience) F.M.K.M.C College (constituent college of Mangalore University) Madikeri-571201 03-12-2013 to till date Professor (25 years) Research Guidance (M.Phil): Sl No Name MPhil Topic of Research 1 Umesh J Akka Mahadevi Bandayada Drsthi Kona awarded 2 Sunanda Hariharana Prabhudevara Ragale Mathu awarded Chamarasanna Prabhuleegalelle ondhu Tahlavanicka Adhayana 3 Shridhara H B Kalegowda Nagavara Avara Katha Sahithya awarded Kuretha Ondhu Adyayana 4 Ambika KM H L Nagegowda Folk Literature awarded Research Guidance (Ph.D): Sl No Name Ph.D Topic of Research 1 Basavaraju Sujana avra Mahakavya Yugasandhy awarded 2 Ravikumara M P Kannada Dalita Sahityadalli awarded Pradeshikate 3 Ramesh A D.k Chowtara Kandabari awarded 4 Shankarappa Kannadadalli Patra Sahitya Submitted Barikere 5 Venkatesh V Kadu kurubara Hadigala Samskrtika Submitted Adhyayana 6 Vinoda raj C C Pravasa Sahitya Pursing 7 Shivaraj S Janapada Mahakavyagalu Pursing Adhayayana 8 Musthapa K H Ki. Rum Ngarajara Vimarseya Madari Pursing 9 Divya shree Paathri Subbana Yakshagaana Pursing Prasangagalu Research Projects (List) (if applicable) Completed : -

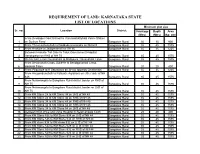

REQUIREMENT of LAND: KARNATAKA STATE LIST of LOCATIONS Minimum Plot Size Sr

REQUIREMENT OF LAND: KARNATAKA STATE LIST OF LOCATIONS Minimum plot size Sr. no. Location District Frontage Depth Area (Mtrs) (Mtrs) (Sq. mtr) From Devalapur Govt School to Thirumashettyhalli Police Station 1 on Soukya Road Bangalore Rural 30 30 900 2 From Thirumashettyhalli to Doddadunnasandra on NH 648 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 3 From Hoskote to Jadigenahalli on SH 95 Bangalore Rural 35 35 1225 Between Hoskote Toll Gate to Taluk Government Hospital, 4 Dandupalya on RHS of NH 75 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 5 On NH 648, From Devanahalli to Mallepura, Devanahalli Taluk Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 From Devanahalli Cross, Sulibele to Bendiganahalli Cross, 6 Hoskote Taluk Bangalore Rural 20 20 400 7 From Piligumpe to K Satyawara on SH 82 towards Chintamani Bangalore Rural 35 35 1225 From Anugondanahalli to Kalkunte Agrahara on either side of NH 8 648 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 From Nelamangala to Bangalore Rural district border on RHS of 9 NH 75 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 From Nelamangala to Bangalore Rural district border on LHS of 10 NH 75 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 11 From KM Stone 24 to KM Stone 34 on LHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 12 From KM Stone 24 to KM Stone 34 on RHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 13 From KM Stone 34 to KM Stone 44 on RHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 14 From KM Stone 44 to KM Stone 54 on RHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 15 From KM Stone 34 to KM Stone 54 on LHS of NH 48 Bangalore Rural 35 45 1575 16 Between KEB office and Usha Hospital in Nelamangala Town Bangalore Rural 20 20 400 17 From -

Introduction to History of Mysore

© 2020 JETIR May 2020, Volume 7, Issue 5 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF MYSORE VIJAYA M. * Asst Professor, Department of History, Government First Grade College For Women, Doddaballapura, Bangalore Rural District. Pin-561203. Abstract: This article refer to the history of Mysore relating to History of Karnataka. Anglo Karnatik war between Haider Ali / Tippu Sultan and Britishes.The data collected for this article is from secondary sources. The overeall objective of this article is to study about the History of pre-independency of India. Introduction: The emergency of Mysore under the Leadership of Haidar Ali which gave formidable challenge to the British imperialism in South India is one of the interesting events in Modern Indian History. Haidar Ali was born at Budikot in the State of Mysore in 1721. His father entered into the military ser ice of the Hindu ruler of Mysore, received the rank of Faujdar and the Jagir Budikot. He died in 1728 when Haidar Ali was only seven years of age. His family suffered very much till Haidar Ali got job in the Army. At that time, the king was Krishna Rai, but the de-facto power of the State was in the hands of his minister Nani Raj. The Karnataka war helped in the rise of Haidar Ali. When Nasir Jang, Nizam of Hyderabad was murdered, a part of his treasure, per chance, fell into the hands of Haidar Ali. He increased the number of his soldiers and trained them on the model of the French army. In 1775, he was appointed the Faujdar of Dindigul. -

5Vf872. NIEPA DC

PJEU SPECTIVli] 1»JLAI\ - DP15P - II UAI^GALOIIIC ItU llA J. IIIST IIICT o f f ic l ; o f Till': s t a t k i'h u j f c t u im 'C io u D is n u c r PUIIMAUY KDllCA l ION I'llOGUAMRIIC (fOvI. I*ress Dr. Aiiihedkar VcmmIIii, Haii^nlorc - 56 0 00 A n r iL 5Vf872. NIEPA DC 372. D09548 K h R - P p am m i h ^documentation om m SfatiOij*! loscitm e of EducatioDni i'*l»nfi)og and Adminittration. 17-B, !Sn Aurobindo Mirf, New Delhi-110016 ^ QOC» N o ................. ...................... i X " 7 ^ ^ ? ' CONTENTS CHAPTER I Introduction ... 1 CHAPTER II Education Profile ... 8 CHAPTER III Management System ... 31 CHAPTER IV Process Of Project Formulation ...34 CHAPTER V Problems And Issues In Primary Education ... 37 CHAPTER VI Goals And Objectives ... 43 CHAPTER VII Strategies And Programme Components ...44 COSTING ... a. For Project Period b. For 1997-98 ANNEXURES: Annexure -1: List Of New Schools Proposed Annexure - 2: List Of LPS To Be Ungraded To V Annexure - 3: List of CRCs proposed ........................ ... .............. ......................... I MAP OF KflRliflTflKfl SHOWmqipREP^RISTRICTS | WITH FEMALE LITERACY (;1991) STATE : 44.34 NATIONAL ; 39.42 PROPOSE0 DPEP-2 BANQALOnE(n) 38.15 BEUTVRY 31.97 91DAR 30.55 GULBARGA 24.49 MYSORE 37.95 BIJAPUR 40.06 DHARWAD 45.20 ■tv ti v.«« - PAjVGALOllERUI^t. 1. Chnnnnpnlnn 2. DevanaliilH 3. DoddaballKpura 4 . Hosakole 5. Knnnknpura 6. Mngadi 7. Nelamangala 8. Rsmanagaram CHAPTER - I INTRODUCTION At the time of independence there existed a single district of Bangalore.