Exchange Rate Issues in the Maldives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

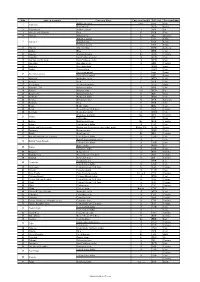

Code List 11 Invoice Currency

Code list 11 Invoice currency Alphabetical order Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region A BTN Bhutan ngultrum BOB Bolivian boliviano AFN Afghan new afghani BAM Bosnian mark ALL Albanian lek BWP Botswanan pula DZD Algerian dinar BRL Brazilian real USD American dollar BND Bruneian dollar AOA Angolan kwanza BGN Bulgarian lev ARS Argentinian peso BIF Burundi franc AMD Armenian dram AWG Aruban guilder AUD Australian dollar C AZN Azerbaijani new manat KHR Cambodian riel CAD Canadian dollar B CVE Cape Verdean KYD Caymanian dollar BSD Bahamian dollar XAF CFA franc of Central-African countries BHD Bahraini dinar XOF CFA franc of West-African countries BBD Barbadian dollar XPF CFP franc of Oceania BZD Belizian dollar CLP Chilean peso BYR Belorussian rouble CNY Chinese yuan renminbi BDT Bengali taka COP Colombian peso BMD Bermuda dollar KMF Comoran franc Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region CDF Congolian franc CRC Costa Rican colon FKP Falkland Islands pound HRK Croatian kuna FJD Fijian dollar CUC Cuban peso CZK Czech crown G D GMD Gambian dalasi GEL Georgian lari DKK Danish crown GHS Ghanaian cedi DJF Djiboutian franc GIP Gibraltar pound DOP Dominican peso GTQ Guatemalan quetzal GNF Guinean franc GYD Guyanese dollar E XCD East-Caribbean dollar H EGP Egyptian pound GBP English pound HTG Haitian gourde ERN Eritrean nafka HNL Honduran lempira ETB Ethiopian birr HKD Hong Kong dollar EUR Euro HUF Hungarian forint F I Code Code Alfa Alfa Country / region Country / region ISK Icelandic crown LAK Laotian kip INR Indian rupiah -

1 Executive Summary the Republic of Maldives Comprises 1,190 Islands

Executive Summary The Republic of Maldives comprises 1,190 islands in 20 atolls spread over 900 km in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives attracts a million tourists annually, and tourism is the growth engine for the economy and accounts for about 70% of GDP. (Contribution is split 30% direct and 70% indirect via transportation, communication, and construction sectors.) Maldives is a multi-party constitutional democracy. In 2008 Parliament ratified a new constitution that provided for the first multi-party presidential elections. In 2012, the first democratically-elected President, Mohamed Nasheed, stepped down, and Vice President Mohamed Waheed became the head of state. In September 7, 2013, Maldives held presidential elections, which international monitors commented as transparent, fair and credible. In a run-off election on November 16, 2014, Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom was elected the new President. Economic growth is projected around 4% in 2014. Maldives faces significant fiscal and balance of payment (BOP) problems. The Maldives Monetary Authority’s (Central Bank) recent projections estimate that the country’s current account deficit will widen to about $270 million in 2014 or 11% of GDP. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has been surprised by the Maldives economic resilience despite long standing economic problems. In December 2009, the IMF approved a $93 million loan for the country. After the first two disbursements, the IMF withheld subsequent disbursements due to concerns that the budget deficit must be further reduced. Maldives economic growth has been mainly powered by tourism. Many international resort operators own and operate resort islands in Maldives; tourism will likely remain the engine of the economy. -

The Maldives a Handbook for US Fulbright Scholars

Welcome to the Maldives A Handbook for US Fulbright Scholars Public Affairs Section U.S. Embassy 44 Galle Road Colombo 3 Sri Lanka Tel: + 94-11-249-8000 Fax: + 94-11-2449070 Email:[email protected] 1 Contents Map of the Maldives The Maldives: General Information Facts The Maldives: An Overview Educational System Pre-departure Official Grantee Status Obtaining your Visa Travel Things to Bring Health & Medical Insurance Customs Clearance Use of the Diplomatic pouch Preparing for change Recommended Reading/Resources In Country Arrival Coping with the Tropical Climate Map of Male What‟s Where in Malé Restaurants Transport Housing Money Matters Banks Communication Shipping goods home Health Senior Scholars with Families Life and Work in the Maldives Contacts List Your Feedback 2 The Maldives The Maldives 3 General Information Facts about the Maldives Population: 395,650 (July 2010 est.), plus over 600,000 tourists annually Capital: Malé Population distribution: Varies significantly from less than 150 on remote islands to 83,000 in Male‟ which is just 2 sq km. Language: Maldivian Dhivehi (dialect of Sinhala, script derived from Arabic), English is spoken by most government officials Adult literacy: 96.3% Religion: Sunni Muslim (100%) Currency: Rufiyaa Life expectancy: men - 72 yrs; women – 76.54 yrs Unemployment 14.4% Gross Domestic product -4 % real growth (2009 est.); 5.8% (2008 est.) Average per capita income US$ 4,200 per annum (purchasing power parity) Land area: 298 sq. Km spread over roughly 90,000 sq km Length: 820 km Width: 80-120 km Coastline: 644 km Climate: Tropical. The monsoons are mild and the temperature varies very little. -

List of Currencies of All Countries

The CSS Point List Of Currencies Of All Countries Country Currency ISO-4217 A Afghanistan Afghan afghani AFN Albania Albanian lek ALL Algeria Algerian dinar DZD Andorra European euro EUR Angola Angolan kwanza AOA Anguilla East Caribbean dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar XCD Argentina Argentine peso ARS Armenia Armenian dram AMD Aruba Aruban florin AWG Australia Australian dollar AUD Austria European euro EUR Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN B Bahamas Bahamian dollar BSD Bahrain Bahraini dinar BHD Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka BDT Barbados Barbadian dollar BBD Belarus Belarusian ruble BYR Belgium European euro EUR Belize Belize dollar BZD Benin West African CFA franc XOF Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum BTN Bolivia Bolivian boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina konvertibilna marka BAM Botswana Botswana pula BWP 1 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Brazil Brazilian real BRL Brunei Brunei dollar BND Bulgaria Bulgarian lev BGN Burkina Faso West African CFA franc XOF Burundi Burundi franc BIF C Cambodia Cambodian riel KHR Cameroon Central African CFA franc XAF Canada Canadian dollar CAD Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo CVE Cayman Islands Cayman Islands dollar KYD Central African Republic Central African CFA franc XAF Chad Central African CFA franc XAF Chile Chilean peso CLP China Chinese renminbi CNY Colombia Colombian peso COP Comoros Comorian franc KMF Congo Central African CFA franc XAF Congo, Democratic Republic Congolese franc CDF Costa Rica Costa Rican colon CRC Côte d'Ivoire West African CFA franc XOF Croatia Croatian kuna HRK Cuba Cuban peso CUC Cyprus European euro EUR Czech Republic Czech koruna CZK D Denmark Danish krone DKK Djibouti Djiboutian franc DJF Dominica East Caribbean dollar XCD 2 www.thecsspoint.com www.facebook.com/thecsspointOfficial The CSS Point Dominican Republic Dominican peso DOP E East Timor uses the U.S. -

List of Currencies That Are Not on KB´S Exchange Rate

LIST OF CURRENCIES THAT ARE NOT ON KB'S EXCHANGE RATE , BUT INTERNATIONAL PAYMENTS IN THESE CURRENCIES CAN BE MADE UNDER SPECIFIC CONDITIONS ISO code Currency Country in which the currency is used AED United Arab Emirates Dirham United Arab Emirates ALL Albanian Lek Albania AMD Armenian Dram Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh ANG Netherlands Antillean Guilder Curacao, Sint Maarten AOA Angolan Kwanza Angola ARS Argentine Peso Argentine BAM Bosnia and Herzegovina Convertible Mark Bosnia and Herzegovina BBD Barbados Dollar Barbados BDT Bangladeshi Taka Bangladesh BHD Bahraini Dinar Bahrain BIF Burundian Franc Burundi BOB Boliviano Bolivia BRL Brazilian Real Brazil BSD Bahamian Dollar Bahamas BWP Botswana Pula Botswana BYR Belarusian Ruble Belarus BZD Belize Dollar Belize CDF Congolese Franc Democratic Republic of the Congo CLP Chilean Peso Chile COP Colombian Peso Columbia CRC Costa Rican Colon Costa Rica CVE Cape Verde Escudo Cape Verde DJF Djiboutian Franc Djibouti DOP Dominican Peso Dominican Republic DZD Algerian Dinar Algeria EGP Egyptian Pound Egypt ERN Eritrean Nakfa Eritrea ETB Ethiopian Birr Ethiopia FJD Fiji Dollar Fiji GEL Georgian Lari Georgia GHS Ghanaian Cedi Ghana GIP Gibraltar Pound Gibraltar GMD Gambian Dalasi Gambia GNF Guinean Franc Guinea GTQ Guatemalan Quetzal Guatemala GYD Guyanese Dollar Guyana HKD Hong Kong Dollar Hong Kong HNL Honduran Lempira Honduras HTG Haitian Gourde Haiti IDR Indonesian Rupiah Indonesia ILS Israeli New Shekel Israel INR Indian Rupee India, Bhutan IQD Iraqi Dinar Iraq ISK Icelandic Króna Iceland JMD Jamaican -

A Sumitography: a Listing of Postage Stamps Celebrating Contributions to Civil and Human Rights by Martin Luther King Jr. and Associates Lillie R

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar Perkins Faculty Research and Special Events Perkins School of Theology Spring 4-10-2018 A Sumitography: A Listing of Postage Stamps Celebrating Contributions to Civil and Human Rights by Martin Luther King Jr. and Associates Lillie R. Jenkins [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/theology_research Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Material Culture Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Graphic Design Commons, Illustration Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, Other History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Public History Commons Recommended Citation Jenkins, Lillie R., "A Sumitography: A Listing of Postage Stamps Celebrating Contributions to Civil and Human Rights by Martin Luther King Jr. and Associates" (2018). Perkins Faculty Research and Special Events. 16. https://scholar.smu.edu/theology_research/16 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the Perkins School of Theology at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Perkins Faculty Research and Special Events by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. [10 April 2018] A Sumitography: A Listing of Postage Stamps Celebrating Contributions to Civil and Human Rights by Martin Luther King Jr. and Associates Prepared by Lillie R. Jenkins Gandhi, Mohandas K. 1969. UNITED KINGDOM, 1'6 s - British shilling. Horizontal, Head- only portrait of Gandhi on left two-thirds of frame - Indian national flag in background. Caption: “Gandhi Centenary Year 1969”. http://www.collectgbstamps.co.uk/explore/issues/?issue=98/ 16 March 2018. -

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

An Analysis of the Denomination Structure of the Maldivian Rufiyaa

RESEARCH AND POLICY NOTES RPN 1-16 APRIL 2016 An Analysis of the Denomination Structure of the Maldivian Rufiyaa Hassan Fahmy Disclaimer: Research and Policy Notes cover research and analysis carried out by the staff of the Maldives Monetary Authority for both internal and external research purposes and policy decisions. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s), and do not necessarily represent those of the MMA. RPN 1-16 AN ANALYSIS OF THE DENOMINATION STRUCTURE OF THE MALDIVIAN RUFIYAA a Hassan Fahmy* Abstract This article provides a summary of the analysis on the optimal currency denomination structure. The basis of this analysis is the D-Metric model which has been successfully applied in a wide range of countries around the globe (Crickett, 2012). Since the release of its first paper banknote series in 1947, the Maldives’ currency series and its denomination structure has had regular and effective upgrades on a timely basis. The entire currency series has been renewed three times in the past including the most recent upgrade to the “Ran Dhihafaheh” series. Structural changes (i.e., introduction of new denominations and conversion of banknotes to same-value coins) have taken place with the renewal of currency series as well as in between such changes. The structural changes made with the release of the new “Ran Dhihafaheh” series—that is the introduction of high- denomination 1,000 rufiyaa banknote and the planned transition of 5 rufiyaa banknote to a same-value coin—have been long overdue as per the results of the D-Metric model. -

February 5 Current Affairs 2018

February 5 Current Affairs 2018 (TNPSC, SSC, BANK, UPSC, RAILWAY) Visit Us - https:// examsdaily.in Face book - ExamsDaily February 5Current Affairs 1. Oil prices sink 1% amid global market plunge, U.S. output spree Brent crude futures were at $66.95 per barrel at 0148 GMT, down 67 cents, or 1%, from the previous close and more than $4 below their high point for 2018, hit last month. U.S. West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude futures were at $63.48 a barrel. That was down 67 cents, or 1%, from their last settlement, and more than $3 off their 2018 high. TAKEAWAYS 1. Oil India - Natural gas liquids company 2. Headquarters - Noida 2. Maldives President declares emergency, former leader arrested The Maldives government declared a state of emergency for 15 days, before heavily armed troops stormed the country's apex court and a former President was arrested amid a spiralling political crisis that followed a surprise Supreme Court ruling last week. In an announcement, President Abdulla Yameen‟s office said: “During this time, though certain rights will be restricted, general movements, services and businesses will not be affected.” TAKEAWAYS 1. Official languages - Maldivian (Dhivehi) 2. Currency - Maldivian rufiyaa 3. Bitcoin PoS maker eyes India entry The Jakarta-based Pundi X is planning to bring cryptocurrency Point of Sale (POS) devices into India. This is significant given that the government, in its Budget last week, had made it clear that cryptocurrencies were not legal tender in India. Jakarta‟s Pundi X plans global roll-out of 1 lakh devices; „India accounts for 10% of bitcoin trade volume‟“We respect the sovereignty of the local currency,” Zac Cheah, CEO of Pundi X told “We have developed a platform based on blockchain technology to facilitate secure transactions.” TAKEAWAYS 1. -

All Countries and Their Currency Names List

List of all Countries and Currencies of the World in 2020 Country Currency Afghanistan Afghan afghani Albania Albanian lek Algeria Algerian dinar Andorra Euro Angola Kwanza Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar Argentina Argentine peso Armenia Armenian dram Australia Australian dollar Austria Euro Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat Bahamas Bahamian dollar Bahrain Bahraini dinar Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka Barbados Barbadian dollar Belarus Belarusian ruble Belgium Euro Belize Belize dollar Benin West African CFA franc Bhutan Bhutanese ngultrum Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Botswana Pula Brazil Brazilian real Brunei Brunei dollar Bulgaria Bulgarian lev Burkina Faso West African CFA franc Burundi Burundian franc Cambodia Cambodian riel Cameroon Central African CFA franc Canada Canadian dollar Cape Verde Cape Verdean escudo Central African Republic Central African CFA franc Chad Central African CFA franc Chile Chilean peso China Chinese Yuan Renminbi Colombia Colombian peso Comoros Comorian franc Costa Rica Costa Rican colon Côte d’Ivoire (Ivory Coast) West African CFA franc Croatia Croatian kuna Cuba Cuban peso Cyprus Euro Czechia Czech koruna Democratic Republic of the Congo Congolese franc Denmark Danish krone Djibouti Djiboutian franc Dominica East Caribbean dollar Dominican Republic Dominican peso Ecuador United States dollar Egypt Egyptian pound El Salvador United States dollar Equatorial Guinea Central African CFA franc Eritrea Eritrean nakfa Estonia Euro Ethiopia Ethiopian -

Monthly Review Coverpage.Psd

The report covers the macroeconomic developments during the month of September 2011. This issue of the Monthly Economic Review contains data available as of 30th November 2011. Monthly Economic Review October 2011 Summary 1 Production and Prices Page No. 1.1 Real GDP is projected to slightly moderate to 8.3 per cent in 2011, following an estimated 3 growth of 9.9 per cent during 2010. 1.2 Tourism sector moderated during the month in comparison to August 2011, however remained 4 bouyant with respect to the corresponding period of 2010. 1.3 The main indicators of the fisheries sector showed mixed results during September 2011. 5 While fish catch (excluding live fish) showed declines, fish export volume and earnings registered growth rates when compared on monthly as well as on annual basis. 1.4 Prices 7 1.4.1 Consumer price inflation for Male’ continued to accelerate, mainly contributed by the 7 increase in prices of food items, cost of transportation and health care. 1.4.2 Commodity price index showed a decline when compared to the previous month while it 8 continued to edge up on an annual basis due to the increase in both global oil and food prices. 1.4.3 The price of crude oil (US West Texas Index) increased slightly on monthly terms while 9 registering a significant growth on annual basis. Meanwhile, domestic petroleum prices remained unchanged during the review month. 2 Public Finance 2.1 According to the government budget 2011 total revenue is projected to increase to Rf8,761.8 11 million while total expenditure is also projected to rise to Rf12,370.8 million resulting in an overall deficit of Rf3,259.3 million. -

DEBT BULLETIN ISSUE 3, June 2019

MINISTRY OF FINANCE, REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES PUBLIC DEBT BULLETIN ISSUE 3, June 2019 Resource Mobilization and Debt Management Department For enquiries: [email protected] Contents Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Disbursed Outstanding Debt ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2. External Debt ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Creditor Breakdown of External Debt ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 2.2 Currency Composition of External Debt ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 External