Feb 2 5 1987

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVERNMENT of TELANGANA (Police Department) Office of The, Commissioner of Police, Hyderabad City. No. Tr.T8/29/2021 Dated: 05

GOVERNMENT OF TELANGANA (Police Department) Office of the, Commissioner of Police, Hyderabad City. No. Tr.T8/29/2021 Dated: 05-01-2021. NOTIFICATION In exercise of the powers conferred upon me under section 21(1) (b) of the Hyderabad City Police Act, I, Anjani Kumar, IPS, Commissioner of Police, Hyderabad City, hereby notify that as per the request of Executive Engineer, Division No. 4A, GHMC for Remodelling of Drain by Construction of RCC Box Drain/RCC Open Drain from Farhat Nagar Junction towards 17-5-349 in Dabirpura Div-Package-I and therefore for the safety of general public the following traffic diversions will be enforced for a period of (01) month w.e.f 06-01-2021 to 05-02-2021. DABIRPURA FLYOVER TOWARDS APAT JUNCTION. A) The Traffic Coming from Dabirpura Flyover towards APAT Junction will be diverted Via Jabbar Hotel, Shaik Fayaz Kaman (Right Turn), Ganga Nagar Nala, Etebar Chowk Jn (Right Turn) APAT Junction. B) The traffic coming from Dabirpura Flyover towards APAT Junction will be diverted Via New Ali Café (Right Turn) Komatwadi Left Turn Noorkhan Bazaar, APAT Junction. APAT JUNCTION TOWARDS DABIRPURA FLYOVER. A) The traffic Coming from APAT Junction towards Dabirpura Flyover will be diverted at Shuttaria Mosque (Left Turn), Noor Khan Bazaar, Komatwadi (Right Turn) New Ali Café Dabirpura,(Left Turn) Dabirpura Flyover.. B) The traffic coming from APAT Junction towards Chanchalguda will be diverted at Dabirpura Kaman (Right Turn), Success School, Ganga Nagar Nala (Left Turn) Bada Bazaar, Yakutpura Railway Station, Chanchalguda. All the Citizens are requested to take alternate routes to reach their destinations and avoid the above routes during the above period and cooperate with the Traffic Police. -

Water Quality Standards and Its Effects on Miralam Tank and Surrounding Environment

IJRET: International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology eISSN: 2319-1163 | pISSN: 2321-7308 WATER QUALITY STANDARDS AND ITS EFFECTS ON MIRALAM TANK AND SURROUNDING ENVIRONMENT Mohd Akram Ullah Khan1, DVS Narsimha Rao2, Mohd Mujahid Khan3, P. Ranjeet4 1 Assistant Professor, Civil Engineering, Guru Nanak Institutions Technical Campus, Telangana, India 2Associate Professor, Civil Engineering, Guru Nanak Institutions Technical Campus, Telangana, India 3Assistant Professor, Civil Engineering, Osmania Univeristy, Telangana, India 4Assistant Professor, Civil Engineering, Guru Nanak Institutions Technical Campus, Telangana, India Abstract Water quality & Soil Degradation impact is determined by chemical analysis and with Remote sensing &GIS ; this data is used for purposes such as analysis, classification, and correlation. The graphical interpretations which assist to understand the hydro- chemical studies, which likely to be effects on the miralam tank and surrounding environment. In this paper the presentation of the statistical and graphical methods used to classify hydro-chemical data is tested, analyzed and compared to minimize the effects. Keywords: Drinking Water Standard, Surface Water Quality, Environmental Degradation, Sustainable Development, Geographic Information System, Graphical Representation, BIS, WHO, Hyderabad, Telangana --------------------------------------------------------------------***---------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. INTRODUCTION The piezometric elevations in Southern part which vary from 470 and 520 m AMSL(above mean sea level) Hyderabad is the capital city of Telangana and consisting of withgentle gradient towards the MusiRiver.In Northern a number of lakes and bunds which were constructed by the part, the piezometric elevation vary from 500 to 563 m rulers of Qutubshahi dynasty, the metro city located at AMSL with steep gradient in NE direction(Fig-6).Ground 17.3850 Latitude and 78.4867 Longitude covers round water was exploited through shallow, large diameter dug 922sq km. -

Places to Visit.Docx

PLACES TO VISIT IN HYDERABAD 1. Ramoji Film City It is world’s best film city. It is a very famous tourist place, it has an amusement park also. It was setup by Ramoji group in 1996. Number of films in Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, Gujarati, Bengali, Oriya, Bhojpuri, English and several TV commercials and serials are produced here every year. 2. Charminar Charminar is very popular tourist destination of Hyderabad. The Charminar was built in 1591 by Mohammed Quli Qutub Shah. It has become a famous landmark in Hyderabad and one among the known monuments of India. A thriving market exists around the Charminar: Laad Baazar is known for jewellery, especially exquisite bangles, and the Pather Gatti is famous for pearls 3. Golconda Fort Golconda is also known as Golkonda or Golla konda. The most important builder of Golkonda wasIbrahim Quli Qutub Shah Wali, it is situated 11 km west of Hyderabad. The Golconda Fort consists of four different Forts. The fort of Golconda is known for its magical acoustic system. 4. Chowmahalla palace Chowmahalla palace was a residence of Nizams of Hyderabad. Chowmahalla Palace was recently refurbished by experts and has been open to public for the last 7 yrs. This palace is situated near charminar. It is worth seeing this palace. The palace also has some Royale vintage cars, cloths, photos and paintings to showcase. 5. Birla Mandir Birla mandir of Hyderabad is a very huge temple. It took 10 years of construction. It is a hindu temple. The architect of the temple is a blend of Dravidian, Rajasthani and Utkala style. -

The Pathetic Condition of Hussain Sagar Lake Increasing of Water Pollution After Immersion of Ganesh-Idols in the Year-2016, Hyderabad, Telangana, India

International Journal of Research in Engineering and Applied Sciences (IJREAS) Available online at http://euroasiapub.org/journals.php Vol. 6 Issue 10, October - 2016, pp. 136~143 ISSN(O): 2249-3905, ISSN(P) : 2349-6525 | Impact Factor: 6.573 | Thomson Reuters ID: L-5236-2015 THE PATHETIC CONDITION OF HUSSAIN SAGAR LAKE INCREASING OF WATER POLLUTION AFTER IMMERSION OF GANESH-IDOLS IN THE YEAR-2016, HYDERABAD, TELANGANA, INDIA Bob Pears1 Head of General Section .J.N. Govt. Polytechnic ,Hyderabad, Telangana, India. Prof. M. Chandra Sekhar2 . Registrar, NIT, Warangal, Telangana,India. Abstract: During the past few years grave concern is being voiced by people from different walks of life over the deteriorating conditions of Hussain Sagar Lake. As a result of heavy anthropogenic pressures, the eco-systems of lake are not only strengthening in its surface becoming poor in quality, posing health hazards to the people living in around close proximity to the lake. Over the years the entire eco-system of Hussain Sagar Lake has changed. The water quality has deteriorated considerably during the last three decades. Over the years the lake has become pollution due to immersion of Ganesh Idols. Many undesirable changes in the structure of biological communities have resulted and some important species have either declined or completely disappeared. Keywords: Groundwater quality, PH , Turbidity,TDS, COD, BOD, DO, before immersing of idols, after immersing of idols. INTRODUCTION Hyderabad is the capital city of Telangana and the fifth largest city in India with a population of 4.07 million in 2010 is located in the Central Part of the Deccan Plateau. -

Telangana Senior Designations.Pdf

HIGH COURT FOR THE STATE OF TELANGANA :: HYDERABAD ****** ROC.NO.2674/SO /2017 Dated: 17.04.2021 NOTIFICATION NO.07 /SO/2021 In exercise of the powers conferred by Section 16 (2) of Advocates Act, 1961 read with Guideline Nos.5 (viii) and 8 - Guidelines for Designation of Advocates as Senior Advocates, High Court for the State of Telangana, the Hon'ble the Chief Justice and Hon'ble Judges of the High Court in the Full Court meeting held on 15.04.2021, have designated 27 Advocates, whose relevant particulars are given hereunder, as Senior Advocates, with effect from 15.04.2021. SI. Name Enrollment No. & No. Date of enrollment 1. Sri Ajay Reddy E TS/807/86, Dt.25.7.1986 2. Sri Anjaneyulu V.S.R. TS/460/84, Dt.06.4.1984 3. Sri Ashok Anand TS/575/87, Kumar S Dt.12.6.1987 4. Sri Chandra Sekhar TS/580/1987, Yamarthi Dt.12.6.1987 5. Sri Chandrasen Re ddy TS/2918/2001, B Dt.22.11.2001 6. Sri Damodar Reddy C TS/26/1988, Dt.22.1.1988 7. Sri Dwarakanath S TS/3199/1995, Dt.20.12.1995 8. Sri Giridhar Rao Aloor TS/201/1985, Dt,21.03.1985 9. Sri Hariharan V TS/432/79, Dt.29.11.1979 10. Sri Hemendranath AP/1370/1992 Reddy R.N Dt.01.10 .199 2 I 11. Sri Madan Mohan TS/ 409 / 1980 Errapally Dt.30.10.1980 I I 12. Sri Mahender Reddy TS/1784/1989, Resu Dt.21.12.1989 I I 13. -

03404349.Pdf

UA MIGRATION AND DEVELOPMENT STUDY GROUP Jagdish M. Bhagwati Nazli Choucri Wayne A. Cornelius John R. Harris Michael J. Piore Rosemarie S. Rogers Myron Weiner a ........ .................. ..... .......... C/77-5 INTERNAL MIGRATION POLICIES IN AN INDIAN STATE: A CASE STUDY OF THE MULKI RULES IN HYDERABAD AND ANDHRA K.V. Narayana Rao Migration and Development Study Group Center for International Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 August 1977 Preface by Myron Weiner This study by Dr. K.V. Narayana Rao, a political scientist and Deputy Director of the National Institute of Community Development in Hyderabad who has specialized in the study of Andhra Pradesh politics, examines one of the earliest and most enduring attempts by a state government in India to influence the patterns of internal migration. The policy of intervention began in 1868 when the traditional ruler of Hyderabad State initiated steps to ensure that local people (or as they are called in Urdu, mulkis) would be given preferences in employment in the administrative services, a policy that continues, in a more complex form, to the present day. A high rate of population growth for the past two decades, a rapid expansion in education, and a low rate of industrial growth have combined to create a major problem of scarce employment opportunities in Andhra Pradesh as in most of India and, indeed, in many countries in the third world. It is not surprising therefore that there should be political pressures for controlling the labor market by those social classes in the urban areas that are best equipped to exercise political power. -

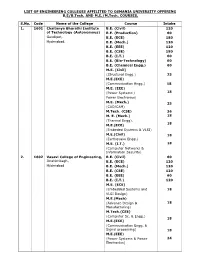

LIST of ENGINEERING COLLEGES AFFILITED to OSMANIA UNIVERSITY OFFERING B.E/B.Tech

LIST OF ENGINEERING COLLEGES AFFILITED TO OSMANIA UNIVERSITY OFFERING B.E/B.Tech. AND M.E./M.Tech. COURSES. S.No. Code Name of the College Course Intake 1. 1601 Chaitanya Bharathi Institute B.E. (Civil) 120 of Technology (Autonomous) B.E. (Production) 60 Gandipet, B.E. (ECE) 180 Hyderabad. B.E. (Mech.) 120 B.E. (EEE) 120 B.E. (CSE) 180 B.E. (I.T.) 60 B.E. (Bio-Technology) 60 B.E. (Chemical Engg.) 60 M.E. (Civil) (Structural Engg.) 25 M.E.(ECE) (Communication Engg.) 18 M.E. (EEE) (Power Systems / 18 Power Electronics) M.E. (Mech.) 25 (CAD/CAM) M.Tech. (CSE) 36 M. E. (Mech.) 18 (Thermal Engg). 18 M.E.(ECE) (Embeded Systems & VLSI) M.E.(Civil) 18 (Earthquake Engg.) M.E. (I.T.) 18 (Computer Networks & Information Security) 2. 1602 Vasavi College of Engineering, B.E. (Civil) 60 Ibrahimbagh, B.E. (ECE) 120 Hyderabad B.E. (Mech.) 120 B.E. (CSE) 120 B.E. (EEE) 60 B.E. (I.T.) 120 M.E. (ECE) (Embedded Systems and 18 VLSI Design) M.E.(Mech) (Advance Design & 18 Manufacturing) M.Tech.(CSE) (Computer Sc. & Engg.) 18 M.E.(ECE) (Communication Engg. & Signal processing) 18 M.E.(EEE) (Power Systems & Power 24 Electronics) 3. 2451 MVSR Engineering College, B.E. (Civil) 120 Nadergul, Saroornagar, B.E. (CSE) 180 Ranga Reddy District. B.E. (ECE) 180 B.E. (Mech.) 120 B.E. (EEE) 120 B.E. (I.T.) 90 B.E. (Automobile) 60 M.E.(Mech) 18 (CAD/CAM) M.Tech.(CSE) 18 M.Tech.(ECE) 36 (Embedded Systems & VLSI Design) 4. -

Current Scenario on Urban Solid Waste with Respect to Hyderabad City

International Journal of Research Studies in Science, Engineering and Technology Volume 3, Issue 12, December 2016, PP 10-13 ISSN 2349-4751 (Print) & ISSN 2349-476X (Online) Current Scenario on Urban Solid Waste with Respect to Hyderabad City Srinivas Jampala1, Ashok Gellu2, Dr.D.Seshi Kala3 Department of Environmental Science, Osmania University, Hyderabad Abstract: Municipal solid waste management is one of the major environmental problems of world. Improper management of municipal solid waste causes hazards to pubic and environment. Various studies reveal that about 90% of MSW is due to improper management of open dumps and landfills, creating problems to public health and the environment. In Hyderabad more amount of solid waste is generating mostly due to the rapid population and industrialization and mainly due to unawareness of solid waste among the public and masses. In the present day, an attempt has been made to provide a comprehensive review of the characteristics, generation, collection and transportation, disposal and treatment technologies of MSW practiced in Hyderabad. The day pertaining to has been carried out to evaluate the current status and identify the major problems. Various adopted treatment technologies for MSW are critically reviewed, along with their advantages and limitations. Keywords: Waste, Municipal solid waste, Urban, Environment, 1. INTRODUCTION Solid waste is a broad term, which encompasses all kinds of waste such as Municipal Solid Waste, Industrial Waste, Hazardous Waste, Bio-Medical Waste and Electronic waste depending on their source and composition. Solid wastes are those organic and inorganic waste materials produced by various activities of the society. (Wolsink 2010) Solid waste management is becoming a major public health and environmental concern in urban areas of many developing countries. -

District Census Handbook, Hyderabad, Part XIII a & B, Series-2

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 2 ANDHRA PRADESH DISTRICT CENSUS. HANDBOOK HYDERABAD PARTS XIII-A & B VILLAGE & TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT S. S. JAYA RAO OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS ANDHRA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF ANDHRA PRADESH 1987 ANDHRA PRADESH LEGISLATURE BUILDING The motif presented on the cover page represents the new Legislature building of Andhra Pradesh State located in the heart of the capital city of Hyderabad. August, 3rd, 1985 is a land mark in the annals of the Legislature of Anohra Pradesh on which day the Prime Minister, Sri Rajiv Gandhi inaugu rated the Andhra Pradesh Legislacure Build ings. The newly constructed Assembly Build ing of Andhra Pradesh is located in a place adorned by thick vegitation pervading with peaceful atmosphere with all its scenic beauty. It acquires new dimensions of beauty, elegance and modernity with its gorgeous and splen did constructions, arches, designs, pillars of various dImensions, domes etc. Foundation stone for this new Legislature Building was laid by the then Chief Minister, Dr. M. Chenna Reddy on 19th March, 1980. The archilecture adopted for the exterior devation to the new building is the same as that of the old building, leaving no scope for differentiation between the two building~. The provision of detached round long columns under the arches add more beauty to the building. The building contains modern amenities such as air-connitioning, interior decoration and reinforced sound system. There is a provision for the use of modc:rn sophisticated electronic equipment for providing audio-system. -

VACCINATION SPECIAL DRIVE CENTERS Sl

VACCINATION SPECIAL DRIVE CENTERS Sl. Zone Circle WardNo Vaccination Center No. 1 Charminar 6-Malakpet 27-Akberbagh Mumtaz Degree & P.G. College,New Malakpet, Hyderabad 2 Charminar 6-Malakpet 28-Azmapura Chanchalguda Govt Junior college 3 Charminar 6-Malakpet 27-Akberbagh Mumtaz College, Akberbagh 4 Charminar 7-Santosh Nagar Gowlipura Mitra Sports Club, Gowlipura 5 Charminar 7-Santosh Nagar ReinBazar SRT Sports Ground, Rein Bazar 6 Charminar 7-Santosh Nagar 38-ISSadan Vinay Nagar Community Hall 7 Charminar 8-Chandrayangutta 41-Kanchanbagh Owaisi Hospital 8 Charminar 8-Chandrayangutta 43-Chandrayangutta Owaisi School, Bandlaguda 9 Charminar 8-Chandrayangutta 44-uppuguda Owaisi School, of excellence, Narqui Phoolbagh Sana garden functionhall, near Sardarmahal muncipal office, 10 Charminar 9-Charminar 32-Patergattti Charminar 11 Charminar 9-Charminar 33-Moghalpura MCH Sports play Ground 12 Charminar 9-Charminar 48-Shalibanda Khilwath Play Ground 13 Charminar 9-Charminar 48-Shalibanda Phoolbagh Play Ground, Rajanna Bhavi 14 Charminar 10-Falaknuma 53-DoodhBowli Quli Qutub Shah Government Polytechnic 15 Charminar 10-Falaknuma 54-Jahanuma Boystown School-I, Jahanuma, Shameergunj 16 Charminar 10-Falaknuma 54-Jahanuma Boystown School-II, Jahanuma, Shamsheergunj 17 Khairatabad 12-Mehdipatnam 70-Mehdipatnam Veternary Function Hall, Shanthi Nagar, Mehdipatnam 18 Khairatabad 12-Mehdipatnam 71-Gudimalkapur Novodaya Community Hall, Gudimalkapur 19 Khairatabad 12-Mehdipatnam 72-AsifNagar KHK Function Hall, Saber Nagar 20 Khairatabad 12-Mehdipatnam 76-Mallepally Bharat Ground, Mallepally Sl. Zone Circle WardNo Vaccination Center No. Madrasa Arabia Mishkatul - Uloom Residential School, Hakeempet 21 Khairatabad 13-Karwan 68-ToliChowki Kunta, opp. Gate No.2, Paramount Hills 22 Khairatabad 13-Karwan 65-Karwan Mesco College of Pharmacy, Mustaidpura, Karwan. -

A S Rao Nagar Branch Mgl 3618 Rajulal Choudary 1-30/60/7

A S RAO NAGAR BRANCH A S RAO NAGAR BRANCH A S RAO NAGAR BRANCH MGL 3618 MGL 3619 MSGL 259 RAJULAL CHOUDARY JAGADISH CHOUDARY P.AMARNATH 1-30/60/7, HNO 1-1-30/171 S/O P.KESHAVULU, G.R. REDDY NAGAR, G.R.REDDY NAGAR, H.NO: 1-11-80, SVS NAGAR, DAMMAIGUDA KAPRA KEESARA RANGA REDDY KUSHAIGUDA, HYD 500062 HYD 500 HYD 500062 A S RAO NAGAR BRANCH A S RAO NAGAR BRANCH ABIDS BRANCH MSGL 260 MSGL 261 MGL 103 A PARTHA SARATHI A PARTHA SARATHI NISHA JAJU HNO 1-86 RAMPALLI DAYARA HNO 1-86 RAMPALLI DAYARA 3-4-516 KEESARA MANDAL RR DIST KEESARA MANDAL RR DIST BARKATPURA HYDERABAD HYDERABAD OPP ARUNA STUDIO HYD 501301 HYD 501301 HYD 500029 ABIDS BRANCH ABIDS BRANCH ABIDS BRANCH MGL 109 MGL 110 MGL 111 MADHAVI TOPARAM MADHAVI TOPARAM MADHAVI TOPARAM FLAT NO 401 1-5-808/123/34/40 FLAT NO 401 1-5-808/123/34/40 FLAT NO 401 1-5-808/123/34/40 HANUMAN ENCLAVE HANUMAN ENCLAVE HANUMAN ENCLAVE MUSHEERABAD NEAR MUSHEERABAD NEAR MUSHEERABAD NEAR EK MINAR ZAMISTANPOOR EK MINAR ZAMISTANPOOR EK MINAR ZAMISTANPOOR HYDERABAD HYDERABAD HYDERABAD HYD 500020 HYD 500020 HYD 500020 ABIDS BRANCH ABIDS BRANCH ABIDS BRANCH MGL 115 MGL 116 MGL 118 SHIVA PRASAD MUTHINENI ETIKAALA VENKATESH KOTHAPALLI SATYANARAYANA 2-2-1167/11/A/3 TILAK NAGAR 5-1-74-VEERA BHRAMENDRA 3-5-1093/10/1 MUSHEERABAD NEW SWAMY NAGAR NEAR KAALI VENKATESHWARA COLONY NALLAKUNTA MANDHIR NARAYANGUDA HYDERABAD HYDERABAD BANDLAGUDA JAGIR HYD 500029 HYD 500044 RAJENDRANAGAR HYD 500086 ABIDS BRANCH ABIDS BRANCH ABIDS BRANCH MGL 119 MGL 129 MGL 130 KOTHAPALLI SATYANARAYANA HANSRAJ NAGIRI SOUJANYA 3-5-1093/10/1 5-1-51,SARDARJI -

5Bb5d0e237837-1321573-Sample

Notion Press Old No. 38, New No. 6 McNichols Road, Chetpet Chennai - 600 031 First Published by Notion Press 2018 Copyright © Shikha Bhatnagar 2018 All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-1-64429-472-7 This book has been published with all efforts taken to make the material error-free after the consent of the author. However, the author and the publisher do not assume and hereby disclaim any liability to any party for any loss, damage, or disruption caused by errors or omissions, whether such errors or omissions result from negligence, accident, or any other cause. No part of this book may be used, reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Contents Foreword vii Ode to Hyderabad ix Chapter 1 Legend of the Founding of the City of Good Fortune, Hyderabad 1 Chapter 2 Legend of the Charminar and the Mecca Masjid 13 Chapter 3 Legend of the Golconda Fort 21 Chapter 4 Legend of Shri Ram Bagh Temple 30 Chapter 5 Legends of Ashurkhana and Moula Ali 52 Chapter 6 Legends of Bonalu and Bathukamma Festivals 62 Chapter 7 Legendary Palaces, Mansions and Monuments of Hyderabad 69 v Contents Chapter 8 Legend of the British Residency or Kothi Residency 81 Chapter 9 Legendary Women Poets of Hyderabad: Mah Laqa Bai Chanda 86 Chapter 10 The Legendary Sarojini Naidu and the Depiction of Hyderabad in Her Poems 92 Conclusion 101 Works Cited 103 vi Chapter 1 Legend of the Founding of the City of Good Fortune, Hyderabad The majestic city of Hyderabad is steeped in history and culture.