Gypsum Trays in Torgac Cave, New Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nancy Hultgren Remembers.Pdf

PART III: Carlsbad Caverns National Park, New Mexico The “main focus” of our five-day trip, in the early spring of 1952, was extended time to visit two locations—Carlsbad Caverns National Park, in the southeastern part of the State of New Mexico, and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico—across the International Border from El Paso, Texas, which lies in the far western tip of Texas. A beautiful morning awaited as we rose from our beds in the small motel in the town of Carlsbad, New Mexico. Out in the parking lot, in front of our room, the Hudson was covered with a thick layer of dust, accumulated during our long drive through Colorado and New Mexico. No rain in sight to help wash the car off, but my dad pulled into a Texaco Gas Station in town to refuel, and have the attendant check the oil and clean the windshields and side windows for us. (While living in Denver, Colorado, my dad often frequented a favorite Texaco Station on Colorado Blvd., not far from our first house on Birch Street.) In a friendly tone, and looking at our license plates, which read “Colorful Colorado,” the station attendant asked, “How far have you folks come? Headed for the Caverns I bet! Any time of year is a good time to go, ya’ know! Doesn’t matter what the temperature is on the outside today, cause deep in the Caverns the temperature is the same year round—56°.” Motel Stevens in Carlsbad, New Mexico. Curt Teich vintage linen postcard. Leaving Carlsbad and the Pecos River Valley behind, my dad pointed the Hudson southwest out of town on US Hwy. -

2015 Visitor Guide Park Information and Maps

National Park Service Wind Cave National Park U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper Annual 2015 Visitor Guide Park Information and Maps The Best of Both Worlds What Lies Below? From Tipis to Tours Back From the Brink Wind Cave National Park is host to Wind Cave is considered sacred and Many national parks are great places one of the longest and most complex culturally significant to many American to view wildlife. However, that has caves in the world. Currently over 143 Indians, and throughout the centuries, not always been the case. In the early miles of twisting passageways reside many tribes lived and traveled within 1900s, many animal populations neared under only 1.2 square miles of surface what would become Wind Cave extinction because of loss of habitat or area, creating a maze of tunnels deep National Park. Who first discovered hunting pressures. below the park's rolling hills. The cave Wind Cave is lost to time, but in 1881, is famous for a rare formation known Tom and Jesse Bingham rediscovered as boxwork. More boxwork is found in the cave when they were attracted Welcome to Wind Cave than all other caves in the to the entrance by whistling noises Wind Cave National Park! world combined. coming out of the cave. This national park is one of the oldest in Portions of Wind Cave are believed to In 1889, the South Dakota Mining the country. Established in 1903, it was the be over 300 million years old, making Company established a mining eighth national park created and the first set it one of the oldest known caves in the claim at Wind Cave and hired J.D. -

Caverns Measureless to Man: Interdisciplinary Planetary Science & Technology Analog Research Underwater Laser Scanner Survey (Quintana Roo, Mexico)

Caverns Measureless to Man: Interdisciplinary Planetary Science & Technology Analog Research Underwater Laser Scanner Survey (Quintana Roo, Mexico) by Stephen Alexander Daire A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the USC Graduate School University of Southern California In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science (Geographic Information Science and Technology) May 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Stephen Daire “History is just a 25,000-year dash from the trees to the starship; and while it’s going on its wild and woolly but it’s only like that, and then you’re in the starship.” – Terence McKenna. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. xi Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................... xii List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................... xiii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................ xvi Chapter 1 Planetary Sciences, Cave Survey, & Human Evolution................................................. 1 1.1. Topic & Area of Interest: Exploration & Survey ....................................................................12 -

Cave & Karst Resource Management Plan, Wind Cave National Park

Cave & Karst Resource Management Plan, Wind Cave National Park 2007 Cave and Karst Resource Management Plan, Wind Cave National Park CAVE AND KARST RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN WIND CAVE NATIONAL PARK March 2007 Recommended By: ___________________________________________________________________ Physical Science Specialist, Date: Wind Cave National Park Concurred By: ___________________________________________________________________ Chief of Resource Management, Date: Wind Cave National Park Approved By: ___________________________________________________________________ Superintendent, Wind Cave National Park Date: 2 Cave & Karst Resource Management Plan, Wind Cave National Park 2007 Cave and Karst Resource Management Plan, Wind Cave National Park Table of Contents I. BACKGROUND....................................................................................................................................................... 4 A. PARK PURPOSE ................................................................................................................................................... 4 B. GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION & DESCRIPTION OF THE PARK ..................................................................................... 4 C. PARK SIGNIFICANCE ............................................................................................................................................ 4 D. SURFACE LAND MANAGEMENT RELATIONSHIP TO KARST............................................................................... 10 II. CAVE AND KARST RESOURCE -

Caves and Karst

CAVES AND KARST An educational curriculum guide on cave and karst resources. 2 week unit Prepared by the National Park Service and their partners at the University of Colorado at Denver. NPS Photo by Rick Wood Page 1 of 120 Table of Contents 1. Foreword Page 3 2. National Standards Page 5 3. Caves and Karst Activity Objectives Page 10 4. Caves and Karst Activities and Lesson Plans Day 1: Interactive Reading Guide Page 14 Reading Guide - Teacher Version Reading Guide - Student Version Day 2: Making a Cave Page 35 Making a Cave - Teacher Version Making a Cave - Student Version Day 3 and 4: Growing Speleothems Page 46 Growing Speleothems - Teacher Version Growing Speleothems - Student Version Day 5: Speleothems: A Webquest Page 62 Speleothems Webquest - Teacher Version Speleothems Webquest - Student Version Day 6: Cave Life: A Jigsaw Activity Page 77 Cave Life - Teacher Version Cave Life - Activity Fact Cards Cave Life - Student Version Day 7, 8, and 9: Present a Cave Page 92 Present a Cave - Teacher Version Present a Cave - Activity Fact Cards: 8 NPS Caves Present a Cave - Student Worksheet Present a Cave - Peer Evaluation Form Present a Cave - Group Member Evaluation Form Day 10: Cave Quiz Game Page 110 (Access game via Views DVD or website) Cave Quiz Game - Teacher Version Page 116 NPS Photo by Rick Wood 5. Glossary of Terms Foreword “Views of the National Parks” (Views) is a multimedia education program that presents stories of the natural, historical, and cultural wonders associated with America’s parks. Through the use of images, videos, sounds and text, Views allows the public to explore the national parks for formal and informal educational purposes. -

Karst Features in the Black Hills, Wyoming and South Dakota- Prepared for the Karst Interest Group Workshop, September 2005

193 INTRODUCTION TO THREE FIELD TRIP GUIDES: Karst Features in the Black Hills, Wyoming and South Dakota- Prepared for the Karst Interest Group Workshop, September 2005 By Jack B. Epstein1 and Larry D. Putnam2 1U.S. Geological Survey, National Center, MS 926A, Reston, VA 20192 2Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey, 1608 Mountain View Road, Rapid City, SD 57702. This years Karst Interest Group (KIG) field trips will demonstrate the varieties of karst to be seen in the semi-arid Black Hills of South Dakota and Wyoming, and will offer comparisons to karst seen in the two previous KIG trips in Florida (Tihansky and Knochenmus, 2001) and Virginia (Orndorff and Harlow, 2002) in the more humid eastern United States. The Black Hills comprise an irregularly shaped uplift, elongated in a northwest direction, and about 130 miles long and 60 miles wide (figure 1). Erosion, following tectonic uplift in the late Cretaceous, has exposed a core of Precambrian metamorphic and igneous rocks which are in turn rimmed by a series of sed- iments of Paleozoic and Mesozoic age which generally dip away from the center of the uplift. The homocli- nal dips are locally interrupted by monoclines, structural terraces, low-amplitude folds, faults, and igneous intrusions. These rocks are overlapped by Tertiary and Quaternary sediments and have been intruded by scattered Tertiary igneous rocks. The depositional environments of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimen- tary rocks ranged from shallow marine to near shore-terrestrial. Study of the various sandstones, shales, siltstones, dolomites and limestones indicate that these rocks were deposited in shallow marine environ- ments, tidal flats, sand dunes, carbonate platforms, and by rivers. -

The Caves & Karst Edition

A Tale of Two Caves: How Is Hurricane Crawl Cave Different From Crystal Cave? Photo courtesy of Dave Bunnell, Under Earth Images. Meet the Scientists Joel D. Despain, Hydrologist: My favorite scientific experiences involve understanding the geomorphic history of a given cave or cave area. Some geomorphic questions are, “Why did the cave form, and why did it form with these particular shapes and patterns? Is it random?” It turns out that caves form in specific ways that tell us about past conditions. The history of the cave, the structure of the rock, the hydrology of the region, the gradient, and other factors all play big roles. Cave geologists are determining different types of caves and how they develop with greater precision every year. They do this through a better understanding of the shapes, forms, and patterns found within caves. This research is creating a much better understanding of caves that then informs our understanding and knowledge of regional geology and geologic history. Benjamin W. Tobin, Hydrologist: Each science experience is amazing, interesting, and fun in its own way. If I had to choose, however, my favorite would be conducting dye traces at the Grand Canyon. This work involves dumping a colored non-harmful dye into the ground up on the plateau above the canyon, then monitoring springs in the canyon to determine where the dye showed up. This is simple science. But the results tell us an incredible amount about how water moves below our feet and it never seems to do what we expect. Greg M. Stock, Geologist: My favorite science experience was mapping caves in Sequoia with Mr. -

Oсhtiná Aragonite Cave (Slovakia): Morphology, Mineralogy and Genesis

Speleogenesis and Evolution of Karst Aquifers The Virtual Scientific Journal ISSN 1814-294X www.speleogenesis.info Oсhtiná Aragonite Cave (Slovakia): morphology, mineralogy and genesis Pavel Bosák1, Pavel Bella2, Václav Cilek1, Derek C. Ford3, Helena Hercman4, Jaroslav Kadlec1, Armstrong Osborne5 and Petr Pruner1 1 Institute of Geology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rozvojová 135, 165 02 Praha 6-Lysolaje, Czech Republic; E-mail: [email protected] 2 Slovak Caves Administration, Hodžova 11, 031 01 Liptovský Mikuláš, Slovak Republic; E-mail: [email protected] 3 School of Geography and Geology, McMaster University, 1280, Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4K1, Canada; E-mail: [email protected] 4 Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences, Twarda 51/55, 00-818 Warszawa, Poland; E-mail: [email protected] 5 Faculty of Education, A35, University of Sydney, N.S.W. 2006, Australia; E-mail: [email protected] Re-published from: Geologica Carpathica 2002, 53 (6), 399-410 Abstract Ochtiná Aragonite Cave is a 300 m long cryptokarstic cavity with simple linear sections linked to a geometrically irregular spongework labyrinth. The limestones, partly metasomatically altered to ankerite and siderite, occur as lenses in insoluble rocks. Oxygen-enriched meteoric water seeping along the faults caused siderite/ankerite weathering and transformation to ochres that were later removed by mechanical erosion. Corrosion was enhanced by sulphide weathering of gangue minerals and by carbon dioxide released from decomposition of siderite/ankerite. The initial phreatic speleogens, older than 780 ka, were created by dissolution in density-derived convectional cellular circulation conditions of very slow flow. -

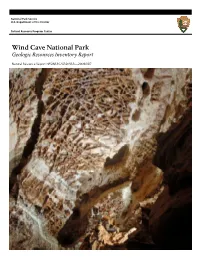

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Wind Cave National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/087 THIS PAGE: Calcite Rafts record former water levels at the Deep End a remote pool discovered in January 2009. ON THE COVER: On the Candlelight Tour Route in Wind Cave boxwork protrudes from the ceiling in the Council Chamber. NPS Photos: cover photo by Dan Austin, inside photo by Even Blackstock Wind Cave National Park Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/087 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 March 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. -

THE MSS LIAISON VOLUME 57 Jerry D

THE MSS LIAISON VOLUME 57 Jerry D. Vineyard Memorial issue July 2017 AFFILIATE ORGANIZATIONS: CHOUTEAU-KCAG-LEG-LOG-MMV-MSM-MVG-OHG-PEG-RBX- SPG-SEMO-MCKC-CCC-CAIRN. Distributed free on the MSS website: http://www.mospeleo,org/ Subscription rate for paper copies is $10.00 per year. Send check or money order made out to the Missouri Speleological Survey to the Editor, Gary Zumwalt, 1681 State Route D, Lohman, MO 65053. Telephone: 573-782-3560. REMEMBERING JERRY D. VINEYARD: A Personal Tribute By H. Dwight Weaver It is difficult to lose a good friend and mentor in your life, but it happened to me on March 31, 2017 when Jerry D. Vineyard passed away after suffering far too long from Parkinson’s disease. I am grateful that he was a part of my life in one way or another for 61 years. I first met Jerry through correspondence in the summer of 1956 after I had become a member of the National Speleological Society (NSS). You could pretty well count on your fingers the number of NSS members in Missouri at that date. The NSS put us in contact with each other. I was fresh out of high school and preparing for my freshman year at the University of Missouri at Columbia where Jerry was beginning his senior year. Just a few days after school started we began caving together, tackling numerous caves in Boone County and making trips to the Devil’s Icebox Jerry Vineyard (left) and Dwight Weaver and further afield to work their raft over the frozen cave stream Carroll Cave. -

Caves & Caverns

Caves & Caverns Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Table 2 ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 3 ................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Table 4 .................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Table 5 .................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 Table 6 ................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Table 7 ................................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Notes: Examples of how to use these tables... ............................................................................................................... 15 Part 2 .................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Acta 2014. PDF De 20 MB

José María Calaforra y Juan José Durán (Editores) Aracena, 2014 Selección de trabajos del Primer Congreso Iberoamericano y Quinto Congreso Español sobre Cuevas Turísticas, celebrado en Aracena (Huelva), en octubre de 2014 Cuevatur. Primer Congreso Iberoamericano y Quinto Congreso Español sobre Cuevas Turísticas / José María ÍNDICE Calaforra y Juan José Durán, eds. - Aracena: Asociación de Cuevas Turísticas Españolas (ACTE), 2014. 1 Turismo Subterráneo Pág. 496 pág. ; 24 cm Eduardo Rebollada, Francisco J. Fernández-Amo y Rafael Pagés-Rodríguez. Turismo Subterráneo en Ex- ISBN: 978-84-617-1908-2 tremadura. Subterranean tourism sites in Extremadura. ......................................................................... 011 1 Turismo Subterráneo. 2 Gestión y Conservación. 3 Control Ambiental. 4 Geoespeleología. 5 Bioespeleología. Francisco-Javier Carrasco-Milara. La transformación de una instalación minera en patrimonio mundial. El caso del Parque Minero de Almadén. The transformation of a mining installation in World Heritage. The Portada: Vistas panorámicas de la Gruta de las Maravillas (Aracena, Huelva) case of Almaden Mining Park. ................................................................................................................ 019 Foto: LovetheFrame (Archivo del Ayuntamiento) Diseño: Manuel Rodríguez Raúl Palacio Portillo. Cueva de Pozalagua. Mejor Rincón 2013 de la Guía Repsol. Pozalagua Cave: Best Corner 2013 in Repsol Motoring Guide. ...........................................................................................