Hermeneutical Resemblance in Rudolf Bultmann and Thich Nhat Hanh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capper 1998 Phd Karl Barth's Theology Of

Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper Selwyn College Submitted for the award of Doctor of Philosophy University of Cambridge April 1998 Karl Barth’s Theology of Joy John Mark Capper, Selwyn College Cambridge, April 1998 Joy is a recurrent theme in the Church Dogmatics of Karl Barth but it is one which is under-explored. In order to ascertain reasons for this lack, the work of six scholars is explored with regard to the theme of joy, employing the useful though limited “motifs” suggested by Hunsinger. That the revelation of God has a trinitarian framework, as demonstrated by Barth in CD I, and that God as Trinity is joyful, helps to explain Barth’s understanding of theology as a “joyful science”. By close attention to Barth’s treatment of the perfections of God (CD II.1), the link which Barth makes with glory and eternity is explored, noting the far-reaching sweep which joy is allowed by contrast with the related theme of beauty. Divine joy is discerned as the response to glory in the inner life of the Trinity, and as such is the quality of God being truly Godself. Joy is seen to be “more than a perfection” and is basic to God’s self-revelation and human response. A dialogue with Jonathan Edwards challenges Barth’s restricted use of beauty in his theology, and highlights the innovation Barth makes by including election in his doctrine of God. In the context of Barth’s anthropology, paying close attention to his treatment of “being in encounter” (CD III.2), there is an examination of the significance of gladness as the response to divine glory in the life of humanity, and as the crowning of full and free humanness. -

The Holy Trinity and Our Lutheran Liturgy Timothy Maschke

Volume 67:3/4 July/October 2003 Table of Contents ~ -- -- - Eugene F. A. Klug (1917-2003) ........................ 195 The Theological Symposia of Concordia Theological Seminary (2004) .................................... 197 Introduction to Papers from the 2003 LCMS Theological Prof essorsf Convocation L. Dean Hempelmann ......................... 200 Confessing the Trinitarian Gospel Charles P. Arand ........................ 203 Speaking of the Triune God: Augustine, Aquinas, and the Language of Analogy John F. Johnson ......................... 215 Returning to Wittenberg: What Martin Luther Teaches Today's Theologians on the Holy Trinity David Lumpp .......................... 228 The Holy Trinity and Our Lutheran Liturgy Timothy Maschke ....................... 241 The Trinity in Contemporary Theology: Questioning the Social Trinity Norman Metzler ........................ 270 Teaching the Trinity David P. Meyer ......................... 288 The Bud Has Flowered: Trinitarian Theology in the New Testament Michael Middendorf ..................... 295 The Challenge of Confessing and Teaching the Trinitarian Faith in the Context of Religious Pluralism A. R. Victor Raj ......................... 308 The Doctrine of the Trinity in Biblical Perspective David P. Scaer .......................... 323 Trinitarian Reality as Christian Truth: Reflections on Greek Patristic Discussion William C. Weinrich ..................... 335 The Biblical Trinitarian Narrative: Reflections on Retrieval Dean 0. Wenthe ........................ 347 Theological Observer -

MICHAEL ROOT School of Theology and Religious Studies the Catholic University of America

MICHAEL ROOT School of Theology and Religious Studies The Catholic University of America EMPLOYMENT 2011-Present: Ordinary Professor of Systematic Theology, The Catholic University of America 2003-2011: Professor of Systematic Theology (also Dean and Vice President for Academic Affairs, 2003-9) Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary, Columbia, SC 1998-2003: Edward C. Fendt Professor of Systematic Theology Trinity Lutheran Seminary, Columbus, Ohio 1988-1998: Research Professor; Director (1991-93; 1995-97) Institute for Ecumenical Research, Strasbourg, France 1980-1988: Assistant (1980-84) and Associate (1984-88) Professor of Systematic Theology Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary 1978-80: Instructor in Religion Davidson College, Davidson, North Carolina OTHER ACTIVITIES 2006-2015: Executive Director, Center for Catholic and Evangelical Theology 2006-Present: Associate Editor, Pro Ecclesia EDUCATION 1979: Ph.D., in Religious Studies - Theology; Yale University 1977: M.Phil., Yale University 1974: M.A., Yale University 1973: A.B., Dartmouth College (Summa Cum Laude, Salutatorian) MEMBERSHIPS Editorial board, Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible, 2003- present Editorial Advisory Board, Ecclesiology, 2006-2015 Board of Directors, Center for Catholic and Evangelical Theology, 2016- present Member, USA Lutheran-Catholic Dialogue, 1998-2010, 2013-present Member, International Lutheran-Catholic Dialogue, 2008-2010 Drafting committee for Lutheran-Episcopal full communion agreement Called to Common Mission, 1997-99 Drafting committee to -

Impassibility and Revelation: on the Relation Between Immanence And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by VID:Open Impassibility and revelation: On the relation between immanence and economy in Orthodox and Lutheran thought Knut Alfsvåg, School of Mission and Theology, [email protected] Abstract What is the relation between divine unchangeability and the reality of change as implied in ideas of creation and redemption? Western Trinitarian theology in the 20th century tended toward emphasizing the significance of change above divine unchangeability, giving it a modalist and Hegelian flavour that questioned the continuity with the church fathers. For this reason, it has been criticized by Orthodox theologians like Vladimir Lossky and David Bentley Hart. Newer scholarship has shown the significance of Luther’s appropriation of the doctrine of divine unknowability and his insistence on the difference between revelation and divine essence for his understanding of the Trinity, which thus may appear to be much closer to the position of the Orthodox critics than to the Lutheran theologians criticized by them. There thus seems to be an unused potential in Luther’s doctrine of the Trinity that should be of interest both for systematic and ecumenical theology. Keywords Theology of the Trinity, Orthodox theology, Lutheran theology, Vladimir Lossky, David Bentley Hart, Martin Luther I. The problem One of the most basic and at the same time most challenging problems of the Christian doctrine of God is the question of the relation between divine unchangeability -

The Psychological Analogy and the Problem Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations A PNEUMATOLOGY OF CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE: THE HOLY SPIRIT AND THE PERFORMANCE OF THE MYSTERY OF GOD IN AUGUSTINE AND BARTH By Travis E. Ables Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion May, 2010 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Paul J. DeHart Professor Ellen T. Armour Professor J. Patout Burns Professor John J. Thatamanil Copyright © 2010 by Travis E. Ables All Rights Reserved TO HOLLY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks are due, first of all, to the members of my dissertation committee, each of whom had a significant impact on my thinking and work. Ellen Armour could always be depended upon for a fascinating and incisive perspective. The idea for this dissertation first took shape in a seminar on Augustine with Patout Burns, whose unparalleled expertise in the great bishop’s theology constantly spurred me on to greater precision and care. My relationship with John Thatamanil was one of the cornerstones of my time in graduate school. John has been a true mentor, and I thank him for his always generous support and advice. Paul DeHart, who directed this dissertation, accepts nothing less than excellence, and I have learned from him, more than anything, to be a careful and sympathetic reader and interlocutor. His encouragement and confidence in this project has been invaluable. There are of course many other professors who had a major part in shaping my thought. -

The Use of Scripture in the Church in the Theologies of Robert Jenson, Kevin Vanhoozer, and Rowan Williams

The Church’s One Foundation: the Use of Scripture in the Church in the Theologies of Robert Jenson, Kevin Vanhoozer, and Rowan Williams by Andrew Albert Fulford A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Wycliffe College and the Theological Department of the Toronto School of Theology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Theology awarded by the University of St. Michael’s College. © Copyright by Andrew Albert Fulford 2012 The Church’s One Foundation: the Use of Scripture in the Church in the Theologies of Robert Jenson, Kevin Vanhoozer, and Rowan Williams Andrew Albert Fulford Master of Arts in Theology University of St. Michael’s College 2012 Abstract Robert Jenson, Kevin Vanhoozer, and Rowan Williams represent three distinct conceptions of how scripture should be used in relation to the five sources of theology: scripture, church, tradition, reason, and experience. Jenson argues that the church, under the guidance of the Spirit, should ultimately determine scripture’s meaning. Vanhoozer contends that scripture should be regarded as highest in authority, not the interpretations of the church or tradition, nor reason or experience. Williams, finally, proposes that Christ, experienced apart from infallible mediators, should ultimately norm how scripture should be used. Reason provides the means, in light of historical testimony, to know Christ’s original significance, while the church and tradition function as further witnesses to Christ as the revelation of God. Evaluating these three positions, it is concluded that all three are consistent, but that Vanhoozer’s best takes into account the facts of history, and has fewer practical problems than Jenson’s position does. -

Basic Christological Distinctions

Volume 64 (2007): 285-304 OQây WESLEY J. WILDMAN Basic Christological Distinctions Abstract: This essay surveys major distinctions used to classify and gain insight into contemporary christologies. clarifying some confusions about them. The focus is on distinctions pertaining to christological starting points (from above, from below), schémas (cosmological. anthropological, eschatological. dialecti cal), styles (historical versus ideal, ontological versus functional), and results (high versus low. literally and figuratively incarnational. absolutist and anti- absolutist or modest). The essay concludes with an argument that the absolutist- modest distinction helps to diagnose several important fault lines in contemporary christology. A quick glance over a forty-one-page stretch of the English translation of Jürgen Moltmann's The Way of Jesus Christ reveals many qualifications of "christology."1 Sometimes the qualifiers are closer to simple adjectives than already established terms or terms likely to catch on. and the meanings of some terms partially overlap. Here are some of the contrasting terms, with rough equivalents indicated by the equal sign: • christology of the way (christologia viae) versus christology of the home country (christologia patriae) • christology of faith versus christology of sight • metaphysical christology ( = orthodox christology = cosmological christol ogy) versus historical christology ( = Jesuology = anthropological christol ogy) versus eschatological christology Wesley J. Wildman is associate professor of -

Postmodernism and the Need for Story and Promise: How Robert Jenson’S Theology Addresses Some Postmodern Challenges to Faith1

Verhoef Postmodernism and the need for story and promise A.H. Verhoef POSTMODERNISM AND THE NEED FOR STORY AND PROMISE: HOW ROBERT JENSON’S THEOLOGY ADDRESSES SOME POSTMODERN CHALLENGES TO FAITH1 ABSTRACT Modernity’s belief that we live in a narratable world (a world with a story) and its confidence in progress (a world with a promise), are terminated by postmodernism’s insights. This is how the American Lutheran theologian Robert Jenson understands the impact of postmodernism. If this is true, it poses great challenges for the Christian faith to be communicated and accepted within this context. This article assesses how Jenson’s theology attempts to address postmodernism’s need for a new story and promise. It concludes that Jenson’s theology, as a Trinitarian theology, forms a coherent answer to these challenges because it is a narrative and eschatological theology. This article indicates, amongst other things the importance of Jenson’s understanding in his theology of the relation between God and time. The significance of Jenson’s approach is that it, firstly, understands the church as a narratable world, with a visible promise, and that it, secondly, follows a characteristically postmodern methodology in addressing these challenges. 1 This article is a revised version of a paper that was delivered at the international conference on “Faith in Face of Secularism” at St. Augustine College in Johannesburg in August 2011. Prof A.H. Verhoef, North-West University. E-mail: Anne.Verhoef@nwu. ac.za. Acta Theologica 2012 32(1): 170-188 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/actat.v32i1.9 ISSN 1015-8758 © UV/UFS <http://www.uovs.ac.za/ActaTheologica> Acta Theologica 2012:1 1. -

The Gospel and Feminism: a Proposal for Lutheran Dogmatics Lois E

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Faculty Publications Faculty & Staff choS larship Summer 1985 The Gospel and Feminism: A Proposal for Lutheran Dogmatics Lois E. Malcolm Luther Seminary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/faculty_articles Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Malcolm, Lois E., "The Gospel and Feminism: A Proposal for Lutheran Dogmatics" (1985). Faculty Publications. 144. http://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/faculty_articles/144 Published Citation Malcolm, Lois. “The Gospel and Feminism: A Proposal for Lutheran Dogmatics.” Word & World 15, no. 3 (1995): 290–98. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty & Staff choS larship at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Word & World Volume XV, Number 3 Summer 1995 The Gospel and Feminism: A Proposal for Lutheran Dogmatics LOIS MALCOLM Luther Seminary St Paul, Minnesota N THE PAST FEW DECADES, THE SOCIAL ROLES OF NORTH AMERICAN WOMEN AND Imen have undergone massive changes; one example is the large number of women who have entered the work force. For many women, especially those who identify themselves as feminists, a significant aspect of this shift has in- volved a radical redefinition of self-understanding, which has entailed an in- creased sense of their self-worth and a spirited critique of any thought pattern or social or political arrangement that suppresses them as women. -

Trinity, Time and Ecumenism in Robert Jenson's Theology

http://ngtt.journals.ac.za Verhoef, AH Northwest University Trinity, time and ecumenism in Robert Jenson’s theology ABSTRACT Robert Jenson, an American Lutheran theologian, is well known as a Trinitarian and ecumenical theologian. In his Trinitarian theology he makes specific choices regarding the relationship between God and time as an attempt to overcome the Hellenistic influences on the early church’s theology, especially about the timelessness of God. Jenson proposes a temporal infinity or timefullness of God, which is central to the relationships within the Trinity. Jenson temporally defines the unity of the Trinity in relation to the claim that God is in fact the mutual life and action of the three persons, Father, Son and Spirit as they move toward the future. In the Trinity’s relationship to time the person Jesus fulfils a very specific role, namely the “specious present”, and this temporal location of Him leads in Jenson’s theology to a very strong ecclesiology and eventually to specific proposals regarding ecumenism. In this article I will investigate this link between Trinity, time and ecumenism in Jenson’s theology. INTRODUCTION Robert Jenson is well known as a significant and prolific writer of Trinitarian theology and ecclesiology. He has written extensively and very creatively about the Trinity for more than forty years. Some of his main works as Trinitarian theologian includes his dogmatic works:Systematic Theology (1997, 1999),1 God after God: The God of the Past and the God of the Future, Seen in the Work of Karl Barth (1969), and Alpha and Omega (1963, 1969). -

How Is Robert Jenson Telling the Story?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE http://scriptura.journals.ac.za/ provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository Scriptura 98 (2008), pp. 231-243 HOW IS ROBERT JENSON TELLING THE STORY? Anné H Verhoef Department of Systematic Theology and Ecclesiology Stellenbosch University Abstract This essay focuses on how the well-known Lutheran theologian Robert Jenson is telling the Christian story. It gives an introduction on Robert Jenson as a person and then shows how his theology can be summarised with reference to three interrelated themes, namely: Trinity, Time and Church. Jenson is a trinitarian theologian. In his understanding that cannot be separated from being a narrative theologian. According to him, the Christian story is a story of hope and its eschatology must be able to survive any criticism – such as the Marxist and the ecological ones. If Jenson thus asks how the End will be, he does not see it as a repristination of the beginning, but as a sublimation – our end is inclusion in God’s life. The article concludes his sort of ‘theology of hope’ is one that can help Christians against the threat of nihilism. Key Words: Robert Jenson, Church, Time, Trinity Introduction To answer the question of how Robert Jenson is telling the story, is a challenging task because of the style and complexity of Jenson’s theology. In this essay I will nevertheless attempt to give an indication of the main thread of the storyline in his theology. I will start by giving an introduction to Jenson as theologian and to his major theological works. -

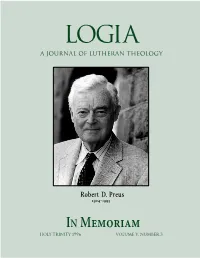

Robert D. Preus ‒

Logia a journal of lutheran theology Robert D. Preus ‒ IN M Holy Trinity 1996 volume v, number 3 ei[ ti" lalei', FREQUENTLY USED ABBREVIATIONS wJ" lovgia Qeou' AC [CA] Augsburg Confession AE Luther’s Works, American Edition logia is a journal of Lutheran theology. As such it publishes Ap Apology of the Augsburg Confession articles on exegetical, historical, systematic, and liturgical theol- BSLK Die Bekenntnisschriften der evangelisch-lutherischen Kirche ogy that promote the orthodox theology of the Evangelical Ep Epitome of the Formula of Concord Lutheran Church. We cling to God’s divinely instituted marks of FC Formula of Concord the church: the gospel, preached purely in all its articles, and the LC Large Catechism sacraments, administered according to Christ’s institution. This LW Lutheran Worship name expresses what this journal wants to be. In Greek, LOGIA SA Smalcald Articles functions either as an adjective meaning “eloquent,” “learned,” SBH Service Book and Hymnal or “cultured,” or as a plural noun meaning “divine revelations,” “words,” or “messages.” The word is found in Peter :, Acts SC Small Catechism :, and Romans :. Its compound forms include oJmologiva SD Solid Declaration of the Formula of Concord (confession), ajpologiva (defense), and ajvnalogiva (right relation- Tappert The Book of Concord: The Confessions of the Evangelical ship). Each of these concepts and all of them together express the Lutheran Church. Trans. and ed. Theodore G. Tappert TDNT Theological Dictionary of the New Testament purpose and method of this journal. LOGIA considers itself a free conference in print and is committed to providing an indepen- TLH The Lutheran Hymnal dent theological forum normed by the prophetic and apostolic Tr Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions.