Flower of Life, Six-Fold Symmetry and Honeycomb Packing of Circles in the Mycenaean Geometry Amelia Carolina Sparavigna, Mauro Maria Baldi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Thesis-Cyprus.Final

MORTUARY PRACTICES IN LC CYPRUS A Comparative Study Between Tombs at Hala Sultan Tekke and Other LC Bronze Age Sites in Cyprus Marcus Svensson Supervisor: Lovisa Brännstedt Master’s Thesis in Classical Archaeology and Ancient History Spring 2020 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History Lund University Abstract This thesis investigates differences and similarities in the funerary material of Late Bronze Age Cyprus in order to answer questions about a possible uniqueness of the pit/well tombs at the Late Bronze Age harbour city of Hala Sultan Tekke. The thesis also tries to explain why these features stand out as singular, compared to the more common chamber tomb, and the reason for their existence. The thesis concludes that although no direct match to the pit/well tombs can be found in Cyprus, there are features that might have had enough similarities to be categorised as such, but since the documentation methods of the time were too poor one cannot say for certain. The thesis also gives an explanation of why not more of these features appear in the funerary material in Cyprus, and the answer is simply that the pit/well tombs were not considered to be tombs but wells. Furthermore, direct parallels to the pit/well tombs can be found on mainland Greece, first and foremost at the south room of the North Megaron of the Cyclopean Terrace Building at Mycenae but also at the Athenian Agora. Key Words Hala Sultan Tekke, Late Cypriote Bronze Age, pit/well tombs, chamber tombs, shaft graves, Mycenae. Acknowledgements This thesis is entirely dedicated to the team of the New Swedish Cyprus Expedition, especially Jacek Tracz who helped me restore the assembled literature in a time of need, and to Anton Lazarides for proofreading. -

The Early History of Beekeeping the Moveable-Frame Hive Lorenzo Langstroth

Lorenzo L. Langstroth and The Quest for the Perfect Hive The early history of beekeeping Lorenzo Langstroth The Moveable-frame Hive The earliest evidence of human interaction with Lorenzo Langstroth was born on Langstroth found that the bees would honey bees dates back 8,000 years to a Meso- December 25, 1810 in Philadelphia, seal the top of the Bevan hive to the lithic cliff painting in Spain that depicts a human Pennsylvania. He attended Yale Col- bars with propolis, meaning that the figure robbing a colony of its honey. Honeycomb lege and was eventually ordained as bars would remain attached to the theft was probably the reason for our ancestors’ a minister. He had a childhood inter- cover when it was removed. In 1851, first intentional encounters with bees. est in insects and was first introduced Langstroth discovered that if he creat- to beekeeping in 1838, when he saw ed a 3/8” space between the cover and a large glass jar containing glistening the bars, the bees would not glue them honeycomb. Langstroth’s first hives, together. He eventually realized that if this 3/8” space surrounded all sides of purchased in 1838, were simple box the frame within the hive box, he could easily lift out the frames without hav- hives with crisscrossed sticks inside ing to cut them away from the hive walls. This “bee space” set Langstroth’s which provided support for honey- hives apart from all the others, resulting in a true moveable-frame hive. The identity of the first beekeepers is unknown, but the oldest historical evi- combs. -

Comb the Honey: Bee Interface Design by Ri Ren

Comb the Honey: Bee Interface Design by Ri Ren Ph.D., Central Academy of Fine Arts (2014) S.M., Saint-Petersburg Herzen State University (2010) B.A.,Tsinghua University (2007) Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology May 2020 © Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2020. All rights reserved. Author ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Program in Media Arts and Sciences May 2020 Certified by ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Neri Oxman Associate Professor of Media Arts and Sciences Accepted by ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Tod Machover Academic Head, Program in Media Arts and Sciences 2 Comb the Honey: Bee Interface Design by Ri Ren Submitted to the Program in Media Arts and Sciences, School of Architecture and Planning on May 2020 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Media Arts and Sciences Abstract: The overarching goal of the thesis is to understand the mechanisms by which complex forms are created in biological systems and how the external environment and factors can influence generations over different scales of space, time, and materials. My research focuses on Nature’s most celebrated architects — bees — and their architectural masterpiece — the honeycomb. Bee honeycombs are wax-made cellular structures of hexagonal prismatic geometries. Within the comb, bees form their nests, grow their larvae, and store honey and pollen. They operate as a “social womb” informed, at once, by communal (genetic) makeup and environmental forces. Resource sharing, labor division, and unique communication methods all contribute to the magic that is the bee “Utopia.” Given that the geometrical, structural, and material make up of honeycombs is informed by the environment, these structures act as environmental footprints, revealing, as a time capsule, the history of its external environment and factors. -

Welcome-To-My-Hive-Honeycomb

Copyright © 2017 Dick Blick Art Materials All rights reserved 800-447-8192 DickBlick.com Welcome to my Hive Materials (required) Sturdy paper for hexagons; Build a “honeycomb” that credits recommend: those who keep the community humming Blick Construction Paper, assorted colors, 9" x 12" (11409-); need one sheet per student (art + social studies) (art + math) (art + science) Pacon 2-Ply Tag Board, Oak, 9" x 12", 100-sheet pack In a honey bee community, one can find a level of coopera- (13111-1103); need one sheet per student tion and collaborative teamwork that exists nowhere else Blick Economy White Posterboard, 5-ply, 22" x 28" on earth. Each bee has an important role to play to guaran- (13109-1102); share two sheets across class tee the survival of the hive. Some bees work in food pro- Decorative or Drawing paper for backgrounds; duction, some in reproduction, some in raising the young, recommend: others as hive security officers — there are even bee house- Decorative Paper Assortment, 1 lb (12440-1001); share keepers! one package across class In the human world, there are workers who keep the Awagami Creative Washi Paper Pack, 1 lb community humming along as well. In this lesson, students (11325-1001); share one package across class are asked to consider the people who provide services Borden & Riley #840 Kraft Paper, 50 sheets, and necessities for them, then design a hexagon cell that 9" x 12" (11519-1023); share one pad across class represents their respective contribution. Cells can be Drawing media for cells; recommend: connected to create a honeycomb-shaped display that Mr. -

Small Hive Beetle Management in Mississippi Authors: Audrey B

Small Hive Beetle Management in Mississippi Authors: Audrey B. Sheridan, Research/Extension Associate, Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology and Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University; Harry Fulton, State Entomologist (retired); Jon Zawislak, Department of Entomology, University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension Service. Cover photo by Alex Wild, http://www.alexanderwild.com. Fig. 6 illustration by Jon Zawislak. Fig. 7 photo by Katie Lee. All other photos by Audrey Sheridan. 2 Small Hive Beetle Management in Mississippi CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Where in the United States Do Small Hive Beetles Occur? .................................. 1 How Do Small Hive Beetles Cause Damage? .......................................................... 1 How Can Small Hive Beetles Be Located and Identifi ed in a Hive? .............................................................................................. 2 Important Biological Aspects of Small Hive Beetles ............................................. 5 Cleaning Up Damaged Combs ................................................................................ 8 Preventing Small Hive Beetle Damage in the Apiary ............................................ 9 Managing Established Small Hive Beetle Populations ....................................... 12 Protecting Honey Combs and Stored Supers During Processing .............................................................................................. -

10. Production and Trade of Beeswax

10. PRODUCTION AND TRADE OF BEESWAX Beeswax is a valuable product that can provide a worthwhile income in addition to honey. One kilogram of beeswax is worth more than one kilogram of honey. Unlike honey, beeswax is not a food product and is simpler to deal with - it does not require careful packaging which this simplifies storage and transport. Beeswax as an income generating resource is neglected in some areas of the tropics. Some countries of Africa where fixed comb beekeeping is still the norm, for example, Ethiopia and Angola, have significant export of beeswax, while in others the trade is neglected and beeswax is thrown away. Worldwide, many honey hunters and beekeepers do not know that beeswax can be sold or used for locally made, high-value products. Knowledge about the value of beeswax and how to process it is often lacking. It is impossible to give statistics, but maybe only half of the world’s production of beeswax comes on to the market, with the rest being thrown away and lost. WHAT BEESWAX IS Beeswax is the creamy coloured substance used by bees to build the comb that forms the structure of their nest. Very pure beeswax is white, but the presence of pollen and other substances cause it to become yellow. Beeswax is produced by all species of honeybees. Wax produced by the Asian species of honeybees is known as Ghedda wax. It differs in chemical and physical properties from the wax of Apis mellifera, and is less acidic. The waxes produced by bumblebees are very different from wax produced by honeybees. -

The Small Hive Beetle a Serious New Threat to European Apiculture

The Small Hive Beetle A serious new threat to European apiculture About this leaflet This leaflet describes the Small Hive Beetle (Aethina tumida), a potential new threat to UK beekeeping. This beetle, indigenous to Africa, has recently spread to the USA and Australia where it has proved to be a devastating pest of European honey bees. There is a serious risk of its accidental introduction into the UK. Introduction: the small hive beetle problem The Small Hive Beetle, Aethina tumida It is not known how the beetle reached either (Murray) (commonly referred to as the 'SHB'), the USA or Australia, although in the USA is a major threat to the long-term shipping is considered the most likely route. sustainability and economic prosperity of UK By the time the beetle was detected in both beekeeping and, as a consequence, to countries it was already well established. agriculture and the environment through disruption to pollination services, the value of The potential implications for European which is estimated at up to £200 million apiculture are enormous, as we must now annually. assume that the SHB could spread to Europe and that it is likely to prove as harmful here The beetle is indigenous to Africa, where it is as in Australia and the USA. considered a minor pest of honey bees, and until recently was thought to be restricted to that continent. However, in 1998 it was Could the SHB reach the UK? detected in Florida and it is now widespread Yes it could. There is a serious risk that the in the USA. -

Hand-Rolled Beeswax Candle

Learning, Leading, Living Hand-Rolled Beeswax Candle Mission Mandate/Project BACKGROUND Connection: Honey bee populations have been in Science and Technology/ trouble in recent years, and there has Entomology/Arts and Crafts been a lot of concern about bees. With Topic: good reason – one in every three Candle making spoonfuls of food we eat has been pollinated by a honey bee. Life Skills: Learning to Learn What is pollination? Pollination is how Audience: plants become fertilized and produce 4-H youth, all ages seeds. When honey bees travel from plant to plant gathering nectar (a sweet Length: sugary substance produced by plants), grains of pollen stick to their 20 minutes bodies. Grains of pollen from one plant fall off the bee into another plant Materials Needed: and voila, the plant is pollinated! One sheet of thin surplus foundation or beeswax Having honey bees around increases the yield of many of our fruit and honeycomb for candles vegetable crops. And of course, the bees convert all of that nectar they 2/0 Candle wick Scissors are gathering into honey! And where do they put all of that honey? Well, bees create little cells from wax that we call a honeycomb. Think of the little cells as tiny buckets. These little buckets are built by the honey bee Link to pictorial on making and placed side by side and are used to store honey, pollen, and to raise beeswax candles: their young. http://www.youtube.com/wa tch?v=cWezDH5jpHg Beeswax Facts Suppliers for beeswax Worker bees produce beeswax from wax glands located in their foundation and wick: abdomen. -

Beekeeping for Beginners

BEEKEEPING FOR BEGINNERS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE • HOME AND GARDEN BULLETIN NO. 158 BEEKEEPING FOR BEGINNERS Keeping honey bees is a fascinat- Beekeeping Equipment ing and profitable pastime that can be enjoyed in several ways. You may The basic equipment you need for want to kee2> bees for the delicious beginning beekeeping should cost no fresh honey they produce, for the more than about $25. This equip- benefits of their valuable services as ment should include the following pollinators for your crops, or per- items : haps just for the fun of learning Hive^ to house your bees. about one of Nature's most interest- Frames^ to support the honey- ing insects. combs in which your bees will store You can keep honey bees success- honey and raise young bees. fully almost any where in the United Smoher^ to blow smoke into the States with relatively little trouble hive, to pacify the bees when you and a minimum of expense. This want to work with them. bulletin supplies you wâth the basic Hive tool^ with which to pry information you should have to get frames apart, to examine the hive started. As a beginning beekeeper, or harvest the honey. you will need only— "F6^7, to protect your face and neck • A few dollars' investment in from bee stings. materials. GloveSy to protect your hands. • A suitable location for bee- Feeder^ to dispense sugar sirup until bees can produce their own Mves. food. • Elementary knowledge of the habits of honey bees. Colony Life Honey bees are social insects. The honey bee (Apis mellifera This means that they live together Linnaeus) is man's most useful in- in a colony and depend on each sect. -

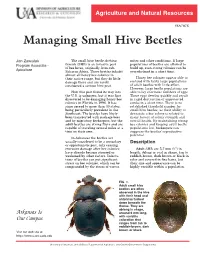

Managing Small Hive Beetles

Agriculture and Natural Resources FSA7075 Managing Small Hive Beetles Jon Zawislak The small hive beetle Aethina mites and other conditions. If large Program Associate tumida (SHB) is an invasive pest popu lations of beetles are allowed to of bee hives, originally from sub- build up, even strong colonies can be Apiculture Saharan Africa. These beetles inhabit overwhelmed in a short time. almost all honey bee colonies in their native range, but they do little Honey bee colonies appear able to damage there and are rarely contend with fairly large populations considered a serious hive pest. of adult beetles with little effect. However, large beetle populations are How this pest found its way into able to lay enormous numbers of eggs. the U.S. is unknown, but it was first These eggs develop quickly and result discovered to be damaging honey bee in rapid destruction of unprotected colonies in Florida in 1998. It has combs in a short time. There is no since spread to more than 30 states, established threshold number for being particularly prevalent in the small hive beetles, as their ability to Southeast. The beetles have likely devastate a bee colony is related to been transported with package bees many factors of colony strength and and by migratory beekeepers, but the overall health. By maintaining strong adult beetles are strong fliers and are bee colonies and keeping adult beetle capable of traveling several miles at a populations low, beekeepers can time on their own. suppress the beetles’ reproductive potential. In Arkansas the beetles are usually considered to be a secondary Description or opportunistic pest, only causing 1 excessive damage after bee colonies Adult SHB are 5-7 mm ( ⁄4") in have already become stressed or length, oblong or oval in shape, tan to weakened by other factors. -

9. Definition and Uses of Honey

9. DEFINITION AND USES OF HONEY WHAT HONEY IS Bees make honey from the nectar that they collect from flowers, other plant saps and honeydew are used to a minor extent. The colour, aroma and consistency of honey all depend upon which flowers the bees have been foraging. Forager honeybees are always female worker bees. The queen bee and drone bees never forage for food. After visiting a flower, the foraging honeybee flies back to her nest that may be in a hollow tree or other natural cavity, or inside a man-made hive. The nectar that she collected from the flower is carried in her honey sac, a modified part of the gut. Once inside the nest, she regurgitates the fluid and passes it through her mouth to one or more 'house' bees, which in turn swallow it and regurgitate it. As each bee sucks the liquid up through her proboscis and into her honey sac, a small amount of protein becomes added and water is evaporated. The proteins added by the bees are enzymes, which convert sugars in the nectar into different types of sugars. The liquid travels through a chain of bees in this way before it is placed in a cell of honeycomb. After the liquid has been placed in the cell, bees continue to process it, and further water evaporates as they do so. The temperature of the nest near the honey storage area is usually around 35 °C. This temperature, and the ventilation produced by fanning bees, causes further evaporation of water from the honey. -

Tombs in Oman

Paul Yule and Gerd Weisgerber Prehistoric Tower Tombs at Shir/Jaylah, Sultanate of Oman The discovery of the towers monuments. First the towers were mapped (Fig. 1–3) and described by G. Weisgerber and 2 . The brief 1995 campaign of the German Ar- the other members of the team Three of the3 chaeological Mission to the Sultanate of towers were excavated, Shi1, Shi2, and Shi23 . Oman took place with the purpose of moni- toring the degree of danger and damage to 1 The present report appeared in the Beiträge zur allgemeinen und archaeological monuments, as a first step in vergleichenden Archäologie 18, 1998, 183–242, ISBN 3-8053-2518- 5. According to some of the locals the mountainside settlement is their protection. The work centred on the 1500 years old. tower tombs at Shir (WilãŊ yat r), within 2 National Survey Authority, negative numbers OM the greater area of Jaylah. The next largest 81 78 015, 017, 019; OM81 78 115, 117, 119; OM81 78 154, 155, 156. town, ɹIbrã , lies 50 air km to the west-south- The map is based on Sheet NF 40-8B, scale 1:100,000 supplemented west (Fig. 1). But other ruins of different by terrestrial survey: M. Eichholz, Th. Klaus 3/95. Cartography: M. periods were recorded as well. These include Eichholz, Th. Klaus 5/95. Owing to the partly extreme wide distanc- three Early Iron Age forts, two at Isma#č yah1 es measured and the collapsed stone around the towers, an accur- and one at Maqέa# ah, as well as a burial acy in the measurement of the diameter measured in decimeters is the maximum which seems reasonable.