Proposed Amendments to LWRP Schedule 17: Salmon Spawning Sites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Detailed Itinerary [ID: 1136]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9604/detailed-itinerary-id-1136-239604.webp)

Detailed Itinerary [ID: 1136]

Daniel Collins - Fine Travel 64 9 363 2754 www.finetravel.co.nz Land of the Rings A tour appealing to those Frodo and Gandalf fans, with visits to official sites used in the filming of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. Starts in: Auckland Finishes in: Queenstown Length: 9days / 8nights Accommodation: Hotel 3 star Can be customised: Yes This itinerary can be customised to suit you perfectly. We can add more days, remove days, change accommodations, mix it up, add activities to suit your interests or simply design and create something from scratch. Call us today to get your custom New Zealand itinerary underway. Inclusions: Includes: All coach transport Includes: All pick ups/drop offs at destinations Includes: Comprehensive tour pack (detailed Includes: 24/7 support while touring in New itinerary, driving, instructions, map/guidebooks, Zealand brochures) Included activity: Auckland to Rotorua including Included activity: Private transfer Christchurch Waitomo and Hobbiton with GreatSights Airport to your accommodation Included activity: Air New Zealand flight Rotorua Included activity: Rotorua Accommodation to to Christchurch Rotorua Airport - Private Transfer Included activity: Rotorua Duck Tours City & Included activity: Lord of the Rings Edoras Tour Lakes Tour Included activity: Christchurch to Queenstown Included activity: One Day in Middle Earth Full via Mount Cook with GreatSights Day Tour Included activity: Safari of the Scenes Wakatipu Included activity: Queenstown to Te Anau with Basin Tour GreatSights Included activity: Pure Wilderness Jet Boat Included activity: Milford Sound Nature Cruise : Meals included: 1 lunch, 1 dinner For a detailed copy of this itinerary go to http://finetravel.nzwt.co.nz/tour.php?tour_id=1136 or call us on 64 9 363 2754 Day 1 Auckland to Rotorua including Waitomo and Hobbiton Experience with GreatSights Take a journey into the heart of the Central North Island, taking in the Waitomo Caves and Hobbiton Movie Set on a full-day sightseeing tour. -

Clifden Suspension Bridge, Waiau River

th IPENZ Engineering Heritage Register Report Clifden Suspension Bridge, Waiau River Written by: Karen Astwood Date: 3 September 2012 Clifden Suspension Bridge, newly completed, circa February 1899. Collection of Southland Museum and Art Gallery 1 Contents A. General information ........................................................................................................... 3 B. Description ......................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Historical narrative .................................................................................................................... 6 Social narrative ...................................................................................................................... 11 Physical narrative ................................................................................................................... 12 C. Assessment of significance ............................................................................................. 16 D. Supporting information ...................................................................................................... 17 List of supporting documents ................................................................................................... 17 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

Mt Potts Lease Number

Crown Pastoral Land Tenure Review Lease name : Mt Potts Lease number : Pc 143 Conservation resources report As part of the process of tenure review, advice on significant inherent values within the pastoral lease is provided by Department of Conservation officials in the form of a conservation resources report. This report is the result of outdoor survey and inspection. It is a key piece of information for the development of a preliminary consultation document. The report attached is released under the Official Information Act 1982. Copied June 2003 RELEASED UNDER THE OFFICIAL INFORMATION ACT CONTENTS PART 1: Introduction.............................................................. 1 PART 2: Inherent Values......................................................... 2 2.1 Landscape.......................................................... 2 2.2 Landforms and Geology.................................... 7 2.3 Climate.............................................................. 8 2.4 Vegetation......................................................... 8 2.4.1 Original Vegetation............................... 8 2.4.2 Indigenous Plant Communities............. 9 2.4.3 Notable Flora....................................... 14 2.4.4 Problem Plants.....................................14 2.5 Fauna .............................................................15 2.5.1 Birds and Reptiles ............................... 15 2.5.2 Freshwater Fauna................................ 19 2.5.3 Invertebrates........................................ 21 2.5.4 Notable -

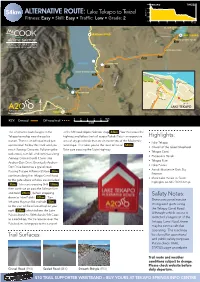

Alternative Route to Twizel

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd GLENTANNER PARK CENTRE LAKE PUKAKI LAKE TEKAPO 54KM LANDSLIP CREEK ALTERNATIVE ROUTE TO TWIZEL TAKAPÕ LAKE TEKAPO MT JOHN OBSERVATORY BRAEMAR ROAD TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO Tekapo Powerhouse Rd TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km Hayman Rd Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS TEKAPO CANAL 9km 15km 24km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road 30km Lakeside Dr TAKAPŌ/LAKE TEKAPO 35km Tek Church of the apo-Twizel Rd Good Shepherd 8 MARY RANGES Dog Monument SALMONFA RM TO SALMON SHOP SH80 TEKAPO RIVER SH8 r s D 44km e r r C e i e Pi g n on SALMON SHOP n Roto Pl o RUATANIWHA i e a e P r r D CONSERVATION PARK o r A Scott Pond STARTING POINT PUKAKI CANAL SH8 Aorangi Cres 8 8 F Rd Lakeside airlie kapo -Te Car Park PUKAKI RIVER Lochinvar Ave Allan St Lilybank Rd Glen Lyon Rd r D n o P l Glen Lyon Rd ilt ollock P Andrew Don Dr am Old Glen Lyon Rd H N Pukaki Flats Track Rise TWIZEL 54km Murray Pl Rankin PUKAKI FLATS OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA SH8KEY: Fitness Easy Traffic Low 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL Onroad left onto Hayman Rd and ride to the Off-road trail 700 start of the off-road Trail on your right Skill Easy Grade 2 Information Centre 35km which follows the Lake Pukaki 600 Picnic Area shoreline. -

South Canterbury Artists a Retrospective View 3 February — 11 March, 1990

v)ileewz cmlnd IO_FFIGIL PROJEEGT South Canterbury Artists A Retrospective View 3 February — 11 March, 1990 Aigantighe Art Gallery In association with South Canterbury Arts Society 759. 993 17 SOU CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 3 INTRODUCTION 6 BIOGRAPHIES Early South Canterbury Artists 9 South Canterbury Arts Society 1895—1928 18 South Canterbury Arts Society formed 1953 23 South Canterbury Arts Society Present 29 Printmakers 36 Contemporaries 44 CATALOGUE OF WORKS 62 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Page S.C. Arts Society Exhibition 1910 S.C. Arts and Crafts Exhibition 1946 T.S. Cousins Interior cat. I10. 7 11 Rev. J.H. Preston Entrance to Orari Gorge cat. I10. 14 13 Capt. E.F. Temple Hanging Rock cat. 1'10. 25 14 R.M. Waitt Te Weka Street cat. no. 28 15 F.F. Huddlestone Opawa near Albury cat. no. 33 16 A.L. Haylock Wreck of Benvenue and City of Perth cat. no. 35 17 W. Ferrier Caroline Bay cat. no. 36 18 W. Greene The Roadmakers cat. 1'10. 39 2o C.H.T. Sterndale Beech Trees Autumn cat. no. 41 22 D. Darroch Pamir cat. no. 45 24 A.J. Rae Mt Sefton from Mueller Hut cat. no. 7O 36 A.H. McLintock Low Tide Limehouse cat. no. 71 37 B. Cleavin Prime Specimens 1989 cat. no. 73 39 D. Copland Tree of the Mind 1987 cat. 1'10. 74 40 G. Forster Our Land VII 1989 cat. no. 75 42 J. Greig Untitled cat. no. 76 43 A. Deans Back Country Road 1986 cat. no. 77 44 Farrier J. -

Lake Tekapo to Twizel Highlights

AORAKI/MT COOK WHITE HORSE HILL CAMPGROUND MOUNT COOK VILLAGE BURNETT MOUNTAINS MOUNT COOK AIRPORT TASMAN POINT Tasman Valley Track FRED’S STREAM TASMAN RIVER JOLLIE RIVER SH80 Jollie Carpark Braemar-Mount Cook Station Rd 800 TEKAPO TWIZEL 700 54km ALTERNATIVEGLENTANNER PARK CENTRE ROUTE: Lake Tekapo to Twizel 600 LANDSLIP CREEK ELEVATION Fitness: Easy • Skill: Easy • Traffic: Low • Grade: 2 500 400 KM LAKE PUKAKI 0 10 20 30 40 50 MT JOHN OBSERVATORY LAKE TEKAPO BRAEMAR ROAD Tekapo Powerhouse Rd LAKE TEKAPO TEKAPO A POWER STATION SH8 3km TRAIL GUARDIAN Hayman Rd SALMON FARM TO SALMON SHOP Tekapo Canal Rd PATTERSONS PONDS 9km TEKAPO CANAL 15km Tekapo Canal Rd LAKE PUKAKI SALMON FARM 24km TEKAPO RIVER TEKAPO B POWER STATION Hayman Road LAKE TEKAPO 30km Lakeside Dr Te kapo-Twizel Rd Church of the 8 Good Shepherd Dog Monument MARY RANGES SH80 35km r s D TEKAPO RIVERe SH8 r r 44km C e i e Pi g n on n Roto Pl o i e a e P SALMON SHOP r r D o r A Scott Pond Aorangi Cres 8 PUKAKI CANAL SH8 F Rd airlie-Tekapo PUKAKI RIVER Allan St Glen Lyon Rd Glen Lyon Rd LAKE TEKAPO Andrew Don Dr Old Glen Lyon Rd Pukaki Flats Track Murray Pl TWIZEL PUKAKI FLATS Mapwww.alps2ocean.com current as of 28/7/17 N 54km OHAU CANAL LAKE RUATANIWHA 0 1 2 3 4 5km KEY: Onroad Off-road trail SH8 Scale The alternative route begins in the at the Mt Cook Alpine Salmon shop 44km . You then cross the Tekapo township near the police highway and follow the trail across Pukaki Flats – an expansive Highlights: station. -

The Glacial Sequences in the Rangitata and Ashburton Valleys, South Island, New Zealand

ERRATA p. 10, 1.17 for tufts read tuffs p. 68, 1.12 insert the following: c) Meltwater Channel Deposit Member. This member has been mapped at a single locality along the western margin of the Mesopotamia basin. Remnants of seven one-sided meltwater channels are preserved " p. 80, 1.24 should read: "The exposure occurs beneath a small area of undulating ablation moraine." p. 84, 1.17-18 should rea.d: "In the valley of Boundary stream " p. 123, 1.3 insert the following: " landforms of successive ice fluctuations is not continuous over sufficiently large areas." p. 162, 1.6 for patter read pattern p. 166, 1.27 insert the following: " in chapter 11 (p. 95)." p. 175, 1.18 should read: "At 0.3 km to the north is abel t of ablation moraine " p. 194, 1.28 should read: " ... the Burnham Formation extends 2.5 km we(3twards II THE GLACIAL SEQUENCES IN THE RANGITATA AND ASHBURTON VALLEYS, SOUTH ISLAND, NEW ZEALAND A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the University of Canterbury by M.C.G. Mabin -7 University of Canterbury 1980 i Frontispiece: "YE HORRIBYLE GLACIERS" (Butler 1862) "THE CLYDE GLACIER: Main source Alexander Turnbull Library of the River Clyde (Rangitata)". wellington, N.Z. John Gully, watercolour 44x62 cm. Painted from an ink and water colour sketch by J. von Haast. This painting shows the Clyde Glacier in March 1861. It has reached an advanced position just inside the remnant of a slightly older latero-terminal moraine ridge that is visible to the left of the small figure in the middle ground. -

NZFSS Newsletter 51 (2012)

New Zealand Freshwater Sciences Society Newsletter Number 51 • December0 | P a g e 2012 ISSN 1177-2026 (print) • ISSN 1178-6906 (online) Contents 1 Introduction to the society .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Editorial .................................................................................................................................................. 5 3 President’s piece .................................................................................................................................... 7 4 He Maimai Aroha – Farewells ................................................................................................................ 9 4 Invited articles and opinion pieces ...................................................................................................... 11 4.1 Prorhynchus putealis: range expansion and call for observations ............................................. 11 4.2 Stealthily slaying the RMA? ......................................................................................................... 14 4.3 A ‘New Deal’ for Fresh Water ..................................................................................................... 15 4.4 A new record for Campbell Island ............................................................................................... 17 4.5 World Class Water and Wildlife ................................................................................................. -

I-SITE Visitor Information Centres

www.isite.nz FIND YOUR NEW THING AT i-SITE Get help from i-SITE local experts. Live chat, free phone or in-person at over 60 locations. Redwoods Treewalk, Rotorua tairawhitigisborne.co.nz NORTHLAND THE COROMANDEL / LAKE TAUPŌ/ 42 Palmerston North i-SITE WEST COAST CENTRAL OTAGO/ BAY OF PLENTY RUAPEHU The Square, PALMERSTON NORTH SOUTHERN LAKES northlandnz.com (06) 350 1922 For the latest westcoastnz.com Cape Reinga/ information, including lakewanaka.co.nz thecoromandel.com lovetaupo.com Tararua i-SITE Te Rerenga Wairua Far North i-SITE (Kaitaia) 43 live chat visit 56 Westport i-SITE queenstownnz.co.nz 1 bayofplentynz.com visitruapehu.com 45 Vogel Street, WOODVILLE Te Ahu, Cnr Matthews Ave & Coal Town Museum, fiordland.org.nz rotoruanz.com (06) 376 0217 123 Palmerston Street South Street, KAITAIA isite.nz centralotagonz.com 31 Taupō i-SITE WESTPORT | (03) 789 6658 Maungataniwha (09) 408 9450 Whitianga i-SITE Foxton i-SITE Kaitaia Forest Bay of Islands 44 Herekino Omahuta 16 Raetea Forest Kerikeri or free phone 30 Tongariro Street, TAUPŌ Forest Forest Puketi Forest Opua Waikino 66 Albert Street, WHITIANGA Cnr Main & Wharf Streets, Forest Forest Warawara Poor Knights Islands (07) 376 0027 Forest Kaikohe Russell Hokianga i-SITE Forest Marine Reserve 0800 474 830 DOC Paparoa National 2 Kaiikanui Twin Coast FOXTON | (06) 366 0999 Forest (07) 866 5555 Cycle Trail Mataraua 57 Forest Waipoua Park Visitor Centre DOC Tititea/Mt Aspiring 29 State Highway 12, OPONONI, Forest Marlborough WHANGAREI 69 Taumarunui i-SITE Forest Pukenui Forest -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 208I7

5 OCTOBER THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 208i7 Waitepipi Stream Tributary of the Mangapu Stream. Map Boddington Range .. Mountain range lying between the Alma reference, approximatelyN. 82/5377. and Acheron Rivers and extending gener Waiteti .. For the locality situated approximately 4 ally north-eastwards from Mount North miles south of Te Kuiti. Also for stream umberland to Trig. D. and viaduct in vicinity. Boundary Stream .. Tributary of the Waiau River. Map re Weraroa .. For Trig. Station in Block XII, Wairoa ference, S. 54/0071. Instead of "Deep Survey District. Map reference, N. 137/ Stream". 293023. Bradley, Mount For feature, height 2,805 ft, in the Banks Whakairi Heights .. For flat topped mountain in the upper Peninsula hills system. Map reference, Kauaeranga River area, Thames County. S. 84/0636. Instead of "Mount Herbert". Map reference, N. 49/156374. Instead of Cow Stream Tributary of Waiau River. Map reference, "Table Mountain". S. 54/9870. Instead of "William Stream". Culverden Range Mountain range commencing at Mount TARANAKI LAND DISTRICT Culverden and extending generally west Name Situation and Remarks erly and northerly to "Pahau Pass". Doubtful Range Mountain range extending generally south Cataract Stream For the tributary of Stony River in Egmont easterly from a point south of Amuri Pass National Park, approximately 30 chains on the main divide to Trig. Z. and lying east of Paul Stream. south of the Doubtful River. The Cataracts For the waterfalls on "Cataract Stream". Glynn Wye Range .. Mountain range commencing at Trig. V, WELLINGTON LAND DISTRICT Mount Longfellow, and extending gener ally easterly to Trig. S, La Grippe, on the Name Situation and Remarks Organ Range. -

Darren's Diaries for West Coast Earth Science

diaries/diary-4 from earthscience91. http://earthscience91.learnz.org.nz/index.php?vft=ear... Previous Darren's Diaries for West Coast Earth Science Diary 4 - Friday 13 March 2009 Field Trip Name: West Coast Earth Science Field Trip Place: Stockton Diary number of total: 4 of 4 Weather: Blue skies for most of the day Where's Darren: Travelling across the Southern Alps (Westport- Hanmer Springs) Hi everyone, Darren here. Low cloud in the Buller Gorge this morning. Image: Heurisko Ltd. We left Westport as the Sun was rising this morning. Heading inland up the Buller River we were met by the sight of low cloud rolling down the gorge towards us. It reminded us of the glaciers that flowed from the hills in this area a few thousand years ago. Our first stop today was the little town of Inangahua Junction. Before 1968 not many people had heard of the place but that all changed at 5.24am on the morning of 24 May 1968. Movement of a fault just a few kilometres to the north of the town caused a magnitude 7 earthquake. Buildings were destroyed by the shaking and by landslides from the surrounding limestone hills. It was a while before the rest of New Zealand knew of the damage as communications to the area were cut. Numerous Inside the musuem at Inanaghua Junction. Image: Heurisko Ltd. aftershocks continued, with a further 14 greater than magnitude 5 that same day. A pilot of a rescue helicopter said he saw the ground "moving like waves" as he flew over the area during one of these aftershocks. -

Report Writing, and the Analysis and Report Writing of Qualitative Interview Findings

HAKATERE CONSERVATION PARK VISITOR STUDY 2007–2008 Centre for Recreation Research School of Business University of Otago PO Box 56 Dunedin 9054 New Zealand CENTRE FOR RECREATION RESEARCH School of Business SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Unlimited Future, Unlimited Possibilities Te Kura Pakihi CENTRE FOR RECREATION RESEARCH ISBN: 978-0-473-13922-3 HAKATERE CONSERVATION PARK VISITOR STUDY 2007-2008 Anna Thompson Brent Lovelock Arianne Reis Carla Jellum _______________________________________ Centre for Recreation Research School of Business University of Otago Dunedin New Zealand SALES ENQUIRIES Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from: Centre for Recreation Research C/- Department of Tourism School of Business University of Otago P O Box 56 Dunedin New Zealand Telephone +64 3 479 8520 Facsimile +64 3 479 9034 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.crr.otago.ac.nz BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCE Authors: Thompson, A., Lovelock, B., Reis, A. and Jellum, C. Research Team: Sides G., Kjeldsberg, M., Carruthers, L., Mura, P. Publication date: 2008 Title: Hakatere Conservation Park Visitor Study 2008. Place of Publication: Dunedin, New Zealand Publisher: Centre for Recreation Research, Department of Tourism, School of Business, University of Otago. Thompson, A., Lovelock, B., Reis, A. Jellum, C. (2008). Hakatere Conservation Park Visitor Study 2008, Dunedin. New Zealand. Centre for Recreation Research, Department of Tourism, School of Business, University of Otago. ISBN (Paperback) 978-0-473-13922-3 ISBN (CD Rom) 978-0-473-13923-0 Cover Photographs: Above: Potts River (C. Jellum); Below: Lake Heron with the Southern Alps in the background (A. Reis). 2 HAKATERE CONSERVATION PARK VISITOR STUDY 2007-2008 THE AUTHORS This study was carried out by staff from the Department of Tourism, University of Otago.